If a patient is poor, he is committed to a public hospital as “psychotic”; if he can afford the luxury of a private sanitarium, he is put there with the diagnosis of “neurasthenia”; if he is wealthy enough to be isolated in his own home under constant watch of nurses and physicians, he is simply an indisposed “eccentric.”

—Pierre Marie Janet, 1930Course of Illness

Reconsidering an epic of illness—Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain.

By Iain Bamforth

Valentine Godé-Darel in a Hospital Bed, by Ferdinand Hodler, 1914. Kunstmuseum Solothurn, Solothurn, Switzerland.

In his influential commentary on Thomas Mann’s 1924 novel The Magic Mountain, the scholar Hermann J. Weigand called it “the epic of disease.” It is more accurate to say that the novel is the epic of a particular disease, tuberculosis, one which has accompanied humans at least since they started building and settling in cities. But it is also, in a broader sense, an epic of illness—an ambitious attempt to show how being ill was experienced at a particular time in a particular culture. In the nineteenth century, and not just in Germany, tuberculosis was the Romantic’s illness; that is, those afflicted with TB were considered sensitive, brooding, creative, and interesting. Mann’s protagonist, Hans Castorp, comes to a sanatorium for a three-week visit with his sick cousin but ends up staying for seven years, adopting the role of the TB patient with a sense of exaltation and even elation. But if Hans is part Romantic hero, he is also part arch-malinger, a young man who does everything he can to join the institutionally coddled life at the mountaintop. He is on a quest: to pass through illness to rediscover the ethics of normal life. That is a search we have all embarked upon. The magic mountain is no longer a retreat or social height; it is our everyday. As the sociologist Nikolas Rose comments, “Like Hans Castorp upon his magic mountain, our stay in the sanatorium is not limited to a brief and terminable episode of illness. It is a sentence without limits and without walls, in which, apparently of our own free will and with the best of intentions on all sides, our existence has become bound to the ministrations and adjudications of medical expertise.”

When Mann wrote his novel, tuberculosis was at a significant juncture in its history. The discovery of the X-ray in 1895 had suddenly made it possible to detect early, active pulmonary forms of the disease. Medicine’s diagnostic capability was, however, decades ahead of its therapeutic capacity, and effective antibacterial treatments for TB did not emerge until after World War II. (Even today, despite the drugs available to treat it, TB remains a major public health problem in many developing countries.) Mann sets The Magic Mountain in 1907 at one of the only therapeutic options then available, the sanatorium. It was an option open only to better-heeled European patients. An Alpine regime of rest and rich food was thought to provide the best chance for recovery from TB, and for the body to reveal its healing wisdom. It certainly isolated patients with active disease (and who were spreading the infection through coughing or sneezing) and created local environments that must have had high circulating levels of airborne bacilli. But that is bacteriology, not the stuff of an epic of illness. There is another quality to the atmosphere of the Haus Berghof on the Davos plateau, to which Mann in the opening pages of his novel propels Hans, who has just passed his engineering exams in Hamburg. The air of the mountains, much as in the Bergfilme (mountain films) that were so popular in the Weimar Republic in the 1920s—and later promoted by the Nazis as the German answer to the Western movie—proves to be anything but pure and clean; it is a narcotic, heady and disorientating.

The Berghof wins Hans over in the way people sent out to the European colonies were accused of going native. Atop this magic mountain, snow falls year-round and all days become “a continuous present, an identity, and everlastingness.” [translation by H. T. Lowe-Porter] The consumptives lie out wrapped in blankets on rattan deck chairs to breathe the glacial air by day, retiring to their rooms to cough out their lungs at night. They live “horizontally,” as Hans’ cousin Joachim Ziemssen complains to him. They form a duplicate world, a society in exile, a pathological circle; yet to Hans the living dead seem remarkably carefree: the foppish Herr Albin likes to scare other patients by pressing a revolver to his temple and Hermine Kleefeld, a leading member of the Half-Lung Club—a select bunch of patients who have undergone a surgical pneumothorax procedure to collapse temporarily the affected lung—whistles at Hans “from somewhere inside.” When not eating copious amounts of food and being slothful—the “rest cure”—they indulge in easygoing eroticism. At the outset of his stay, Hans disdains the amorous sounds of the Russian couple in the next room “[whose] game had passed quite frankly over into the bestial.” In general, opting for the sick role at the sanatorium appears to open the door on a life of constant good spirits and endless fun.

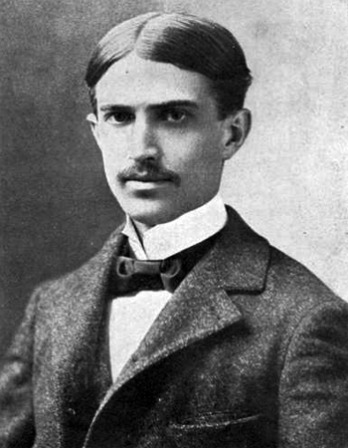

Improbable as it may sound to anyone who has read, or even held, the 716-page novel, The Magic Mountain started out as a short story, in fact as a pendant to Mann’s famous tale of disease and eroticism, Death in Venice. Mann had just finished his work on that novella when he visited his wife Katia at the Davos sanatorium in May and June 1912, and told one of his correspondents that he was working on a new project, a “kind of countertext” to the Aschenbach story. Both offer a journey out of humdrum life into a luxury setting, exploring an existentially threatening situation subsequent to falling in love; but while Aschenbach is degraded by illness, Castorp, as Susan Sontag notes in Illness as Metaphor, is “promoted.” In his essay “The Making of The Magic Mountain,” published in 1953, Mann writes, “The atmosphere was to be that strange mixture of death and lightheadedness I had found at Davos. There was to be a simple-minded hero, in conflict between bourgeois decorum and macabre adventure. Then the First World War broke out. It did two things: put an immediate stop to my work on the book, and incalculably enriched its content at the same time.”

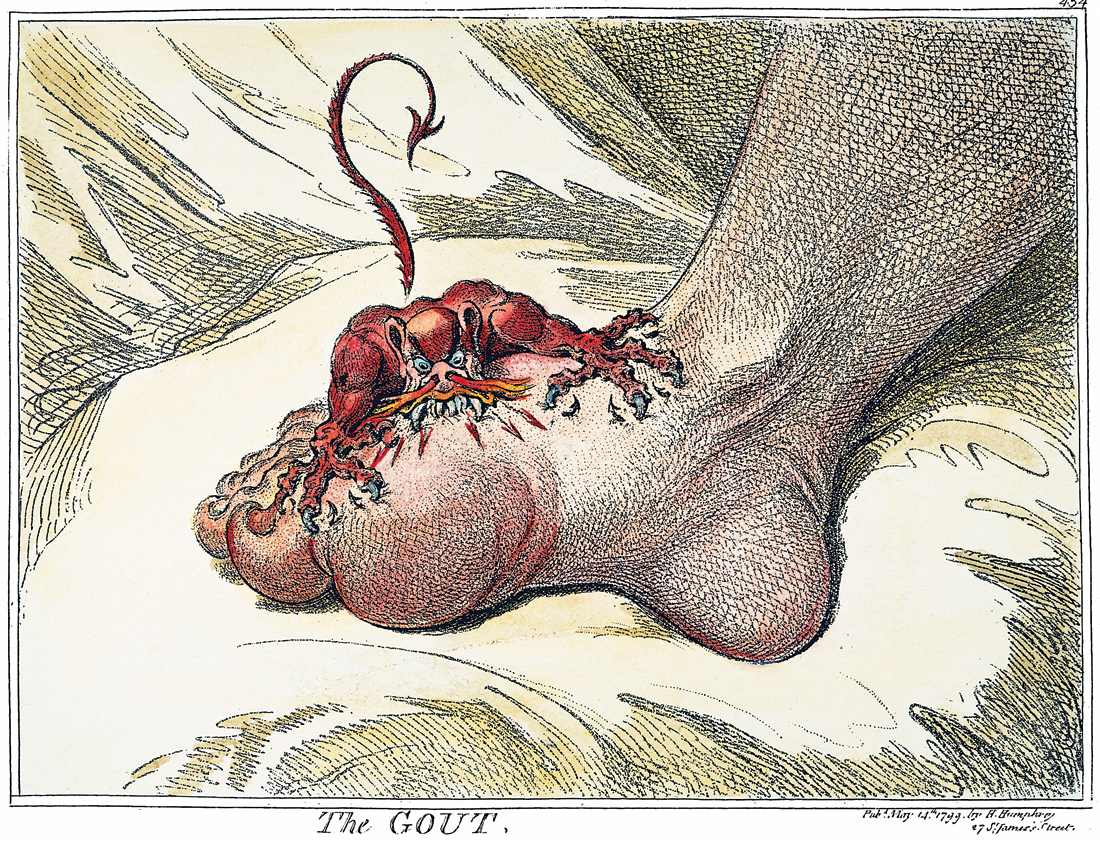

The Gout, etching by James Gillray, 1799.

Mann initially saw the war as a chance for the Fatherland to demonstrate its spiritual superiority to the crassly materialistic culture of France and Britain. In 1918, he had published Reflections of a Non-political Man, a passionate and patriotic defense of Germany’s participation in the war. As an arch-nationalist, he had argued against the liberal position of his own brother Heinrich, a committed Francophile. By 1922, in a speech on the “German Republic” two years before The Magic Mountain appeared, Mann had completely changed his position. He was now a supporter of democratic republicanism, of accommodation with the forces of what Bertolt Brecht called “the bad new” world. The Weimar period was to be an era of consumerism, matter-of-factness, and cynicism. Older modes of identity began to crumble. Mann’s task, since he identified so much with his native country, was how to represent these new values to the many readers who, like him, still believed in the “suffering and greatness” of a bygone era.

One aspect of the prewar days that Mann insisted on retaining was the classic humanism of German culture, of which Johann Wolfgang von Goethe may serve as the emblematic figurehead. It is in Goethe’s first novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther, his story of an ardent soul and teenage suicide, that we find the origins of the descriptions of nature that break into Hans’ stolid consciousness. “Stupendous mountains encompassed me, abysses yawned at my feet, and cataracts fell headlong down before me.” Goethe’s protagonists—notably the titular lead of his second novel, Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship—leave imprints all over Mann’s novel. Hans is still ingenuous, in the sense that he has not had his native wit and intuition educated entirely out of him: early in the novel the narrator calls him “this still-unwritten page.” From a rather philistine young man whose bedside reading material when he arrives at the Berghof is a technical book called Ocean Steamships, he has by the end of The Magic Mountain acquired the kind of revelatory hermetic knowledge of “what holds the world together in its innermost,” to which Goethe alludes in his Faust. Hans also acquires a glimpse of the innermost force that holds him together. Like Faust, he seems to make a bargain: to trade his lung for a look inside himself, a look that the doctor at Davos—and his X-ray machine—are more than willing to provide.

One morning Hofrat Behrens, the jovially cynical superintendent of the Berghof, tells Hans that he looks unwell—“sine pecunia,” he adds twice, although he clearly has a vested interest in recruiting patients. Hans, alarmed and fascinated, buys a state-of-the-art thermometer (which is “like a jewel”) and begins to monitor himself four times a day, for seven minutes at a time. In a rather innocent manner, Hans’ adoption of routine fever-measuring foreshadows our more technically elaborate obsession with self-monitoring. Meanwhile, Joachim, the diagnosed patient, chafes under his enforced leisure, and hankers to return to his flatland life in the army. Behrens—tongue not entirely in cheek—tells Hans that he’ll make a “better patient.” As Hans is just about to embrace the possibility that he too might be getting sick, he meets the beguiling Russian, Clavdia Chauchat. With her blithe habit of slamming the dining room door, this “Kirghiz-eyed” woman awakens his senses (though it takes him months before he can work up the courage to address her). Clavdia’s anarchic Eastern spirit undermines the ordered reason of social conventions such as marriage—and even the smooth running of the sanatorium. Such a troubling influence cannot go unchallenged, and Mann has her rhetorical counterpart already set up: Ludovico Settembrini. The Italian scholar Settembrini requests to be Hans’ tutor, his humanistic pedagogue, who regularly urges him to return to his real life. Settembrini, the great defender of rationalism, has no sympathy for the supposition that illness might make a person interesting. “Disease and despair are often only forms of depravity,” he remarks. Perfectly well people, he warns Hans, have even been known to insist on staying on the mountain.

If we didn’t suspect that Hans was infected with something—his blinding love for Clavdia, perhaps, or for the otherworldly life up in the mountains—Behren’s diagnosis settles the issue. Hans has a “moist spot” on his lung and scars from a childhood infection. Suddenly, we are informed that the mountain atmosphere is just as liable to bring out an incipient case of TB as it is to resolve an established one; alternatively, Hans may have played the sick role too well, the detection of TB simply the finishing touch on his performance. In either case, he now has a chance to show just how good a patient he can be. Behrens soon brings Hans to the X-ray room, where the machine reveals to Hans “what he never thought it would be vouchsafed him to see: he looked into his own grave.” The flesh can be penetrated, and its parts viewed as negative images quite separately from the living, breathing body, and held up to the light for scrutiny. Hans has become exquisitely image conscious, like the other patients of the Berghof who pass the time observing the small X-ray plates, their interior portraits. These ghostly aseptic images have become a consolation prize for their inability to grasp the reality of what afflicts them. As Bettyann Holtzmann Kevles writes in her history of medical imaging Naked to the Bone, the X-ray undermined not only Victorian ideas of propriety and private parts, it altered “the self-perception of an entire culture.” Since then, of course, imaging techniques have become ever more sophisticated, revealing first soft tissues, then with the advent of ultrasound, nuclear magnetic resonance, and positron-emission tomography, the detailed internal structure and even metabolic activity of living tissues.

Now that Hans can safely call the sanatorium his home, he is free to pursue his love interest. To his vexation, Clavdia Chauchat refuses to take his illness seriously. Settembrini, of course, detests her, viewing her as a telluric force that will disrupt the brotherhood of enlightened men. Yet the “fatal, carousingly sweet hour,” that Hans enjoys with her on Carnival night—seven years at a sanatorium for one hour of bliss—opens his pedestrian soul to its own depths. Hans declares his love for her in the most stilted French. “Let me take in the scent of your pores and brush the down—O human image made of water and protein, destined for the shape of the tomb: let me perish, my lips against yours!” Hans verbally lays bare his soul—in the kind of purple prose an engineer might drum up—and then he receives her soul physically, in the form of her most intimate possession, the X-ray plate of her lung. Clavdia leaves the sanatorium almost immediately after their night of passion, and Hans embarks on a long course of reading and studying. The cure for heartbreak becomes a curriculum.

In Clavdia’s absence, Hans takes up the part of the medieval Everyman in a morality play, with Settembrini and his new foil, Leo Naphta, a Polish Jew converted to Catholicism, as God and the Devil fighting it out for the young man’s soul. Many of their arguments do indeed offer “the great disputation on sickness and health” that Mann hoped for his novel. For Settembrini, the purpose of modern medicine is, through hygiene and social reform, to allow reason and enlightenment to triumph over disease. This fight against the sufferings of the flesh is a moral one, since health is identified with virtue. For Naphta, nothing can be more detestable than this ethics of normal living. True spirituality and freedom are not bound to an anodyne veneration of the healthy body but to a stoic acceptation of bodily infirmity and suffering. To be human is to be ill. “Man was essentially ailing, his state of unhealthiness was what made him man. There were those who wanted to make him ‘healthy,’ to make him ‘go back to nature,’ when, the truth was, he never had been ‘natural.’” Naphta, sounding at times uncannily like Michel Foucault, argues that the normal has always lived on “the achievements of the abnormal.” The arguments run on for a hundred pages or so before Clavdia returns in the company of her lover, Mynheer Pieter Peeperkorn, a retired colonial coffee-planter from the Netherlands. As one of the oldest characters in the book, Peeperkorn—the kind of person usually described as “larger than life”—tries to teach Hans how to rise above the intellectual antinomies and be aware of the “sacraments of pleasure.” According to Peeperkorn, Hans’ duty is to feel, to act on his thoughts, and not merely discuss—with Settembrini and Naphta as alibis—the possibilities open to him.

But this irruption of vitalist philosophy into the becalmed atmosphere of the Berghof is not enough to make Hans quit the magic mountain. His explorations of the occult—in which he is encouraged by Behrens’ assistant, the off-putting psychoanalyst Krokowski—bring him to another dark room and an apparition of his dead cousin—Joachim died at the sanatorium after a brief return to military life—dressed in his uniform. This section entirely reverses the enlightenment of the earlier X-ray room experience. “Hans Castorp liked the darkness, it mitigated the queerness of the situation. And in its justification he recalled the darkness of the X-ray room, and how they had collected themselves, and ‘washed their eyes’ in it, before they ‘saw.’” But Hans refuses Krokowski’s command that he speak to the wraith of Joachim and, in a Settembrini-like gesture, throws on the light. An abrupt end is also in sight for the debating circle. After a general deterioration in the atmosphere at the Berghof (mirroring the conflicts in Europe that led up to the war), Settembrini and Naphta’s intellectual flights sink into bickering and vindictiveness, with the former accusing the latter of “misleading unsettled youth.” A duel is arranged. Settembrini casually fires his revolver into the air, refusing to shed human blood and offering his body to his rival. Naphta, bitter at this betrayal, shouts “Coward!” and shoots himself through the head. It is the climax of the novel, though it is hardly its resolution.

The gunshot on the mountain signals the one soon heard more than four hundred miles away in the flatlands: the Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s assassination prevents Hans from eking out his life indefinitely at the sanatorium. The first rumblings of the Great War finally enter the novel, like chairs being toppled in a drawing room. In the final, filmlike epilogue to the novel, we see Hans advancing over the mists of a battlefield, bayonet in his hand, humming to himself the Schubert song “The Linden-tree” that once besotted him in the Berghof. He had first listened to it on the gramophone, another kind of machine brought in to lighten the lives of the Berghof guests.

Mann’s conclusion is one of most unsettling aspects of the novel, and not just because it falls in the shadow of the mountain of text that precedes it. As the first soldiers to go over the top in 1914 soon realized, they were the poor, deluded heralds to the first technological war, one to be run under the guidance of the coolly functional engineer types Hans is supposed to be. The cruelest irony of all is that Castorp’s Bildung or education—with his return to the land of normal life in the flatlands—is his likely death in the mud of a war set to nullify the entire world of values that created him. Any writer who presumed to address the topic of the war after 1918 would have to walk over dead bodies too. Mann’s farewell to “life’s delicate child” is barely camouflage enough to prevent us from seeing that treading on corpses is precisely what both are doing in the final scene. The young soldiers, those “flushed” lads, have the same feverish face Hans had in his heightened state on the magic mountain.

In his English comments for the American edition of The Magic Mountain, Mann wrote, “Such institutions as the Berghof were a typical prewar phenomenon. They were only possible in a capitalistic economy that was still functioning well and normally. Only under such a system was it possible for patients to remain there year after year at the family’s expense. The Magic Mountain became the swan song of that form of existence. Perhaps it is a general rule that epics descriptive of some particular phase of life tend to appear as it nears its end. The treatment of tuberculosis has entered upon a different phase today; and most of the Swiss sanatoria have become sports hotels.”

While it is true that the discovery of streptomycin by Albert Schatz in 1943, the first effective pharmaceutical cure for TB, led to the closure on a massive scale of spas and sanatoriums, the phenomenon of leaving the “flatland” for what might be called recreational medical treatments has actually grown considerably. In some European countries these treatments are even funded by the national health systems. As the postwar French and German governments were the first to grasp, medical tourism could be seamlessly integrated into the macroeconomics of their respective national economies. The word Mann used to describe the heightening of Hans Castorp’s personality, “Steigerung,” now has its primary meaning in the economic field. It denotes increased productivity. Mann had not fully anticipated how his grand bourgeois families would be replaced by mass consumers with a sense of entitlement and enormous appetites for restorative leisure. In the mass society, that delicious temporary sensation of being above the fray, embedded in the elements in a luxurious rarefaction (most pleasurably in the amniotic surround of a spa), can be had collectively. Now, as employees who have paid their medical insurance premiums, clients can ask their doctor to send them for a “cure,” where they can partake in an atmosphere of discipline, segregation, and submission to orders from above. These are the naturalistic “experiments in regeneration” that Naphta ridicules in the novel.

Committed now to nothing more than our well-being, our principal guides in the art of living are doctors, not philosophers. Settembrini’s ethics prevail, even though the radical critique of medicine’s largely humane accomplishments sounds like Naphta. The contemporary German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, in the third volume of his massive phenomenological account of modernity, Spheres, a book with something of the grand synoptic reach of Mann’s novel, lists the zones in our culture where we can find something of the magic mountain atmosphere: “Even where illness does not define the very modus vivendi, it remains in the background as a constant possibility: fitness scenes, wellness and diet regimes, the smoothly organized and inward-looking worlds of the spa towns, the balneological retreats and the high-altitude castles for coughers would be inconceivable without it.” These are the various stations of the therapeutic good life. As an older Naphta avatar, Carl Jung, once wrote, “The gods have become diseases.” If health is the highest good, then diseases have surely become our deities, as menacing and unpredictable as the old kind.