On the assumption that Western Europe will be rescued from communist control, the relationships between Great Britain and the continental countries, on the one hand, and between Great Britain and the United States and Canada on the other, will become for us a long-term policy problem of major significance. The scope of this problem is so immense and its complexities so numerous that there can be no simple and easy answer. The solutions will have to be evolved step by step over a long period of time. But it is not too early today for us to begin to think out the broad outlines of the pattern which would best suit our national interests.

In my opinion, the following facts are basic to a consideration of this problem.

1. Some form of political, military, and economic union in Western Europe will be necessary if the free nations of Europe are to hold their own against the people of the east united under Moscow rule.

2. It is questionable whether this union could be strong enough to serve its designed purpose unless it had the participation and support of Great Britain.

3. Britain’s long term economic problem, on the other hand, can scarcely be solved just by closer association with the other Western European countries, since these countries do not have, by and large, the food and raw material surpluses she needs; this problem could be far better met by closer association with Canada and the United States.

4. The only way in which a European union, embracing Britain but excluding Eastern Europe, could become economically healthy would be to develop the closest sort of trading relationships either with this hemisphere or with Africa.

It will be seen from the above that we stand before something of a dilemma. If we were to take Britain into our own U.S.-Canadian orbit, according to some formula of “union now,” this would probably solve Britain’s long term economic problem and create a natural political entity of great strength. But this would tend to cut Britain off from the close political association she is seeking with continental nations and might therefore have the ultimate effect of rendering the continental nations more vulnerable to Russian pressure. If, on the other hand, the British are encouraged to seek salvation only in closer association with their continental neighbors, then there is no visible solution of the long-term economic problem of either Britain or Germany, and we would be faced, at the termination of Economic Recovery Plan, with another crises of demand on this country for European aid.

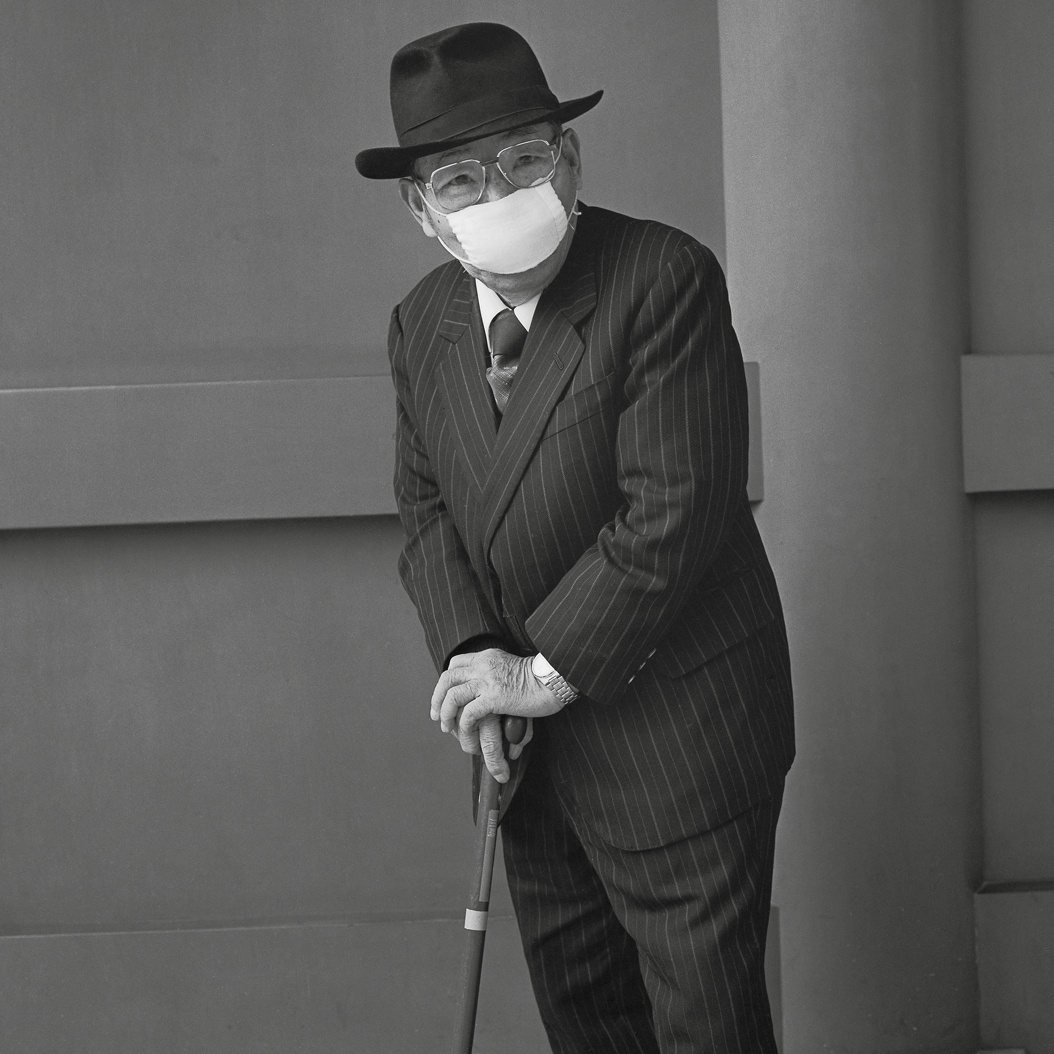

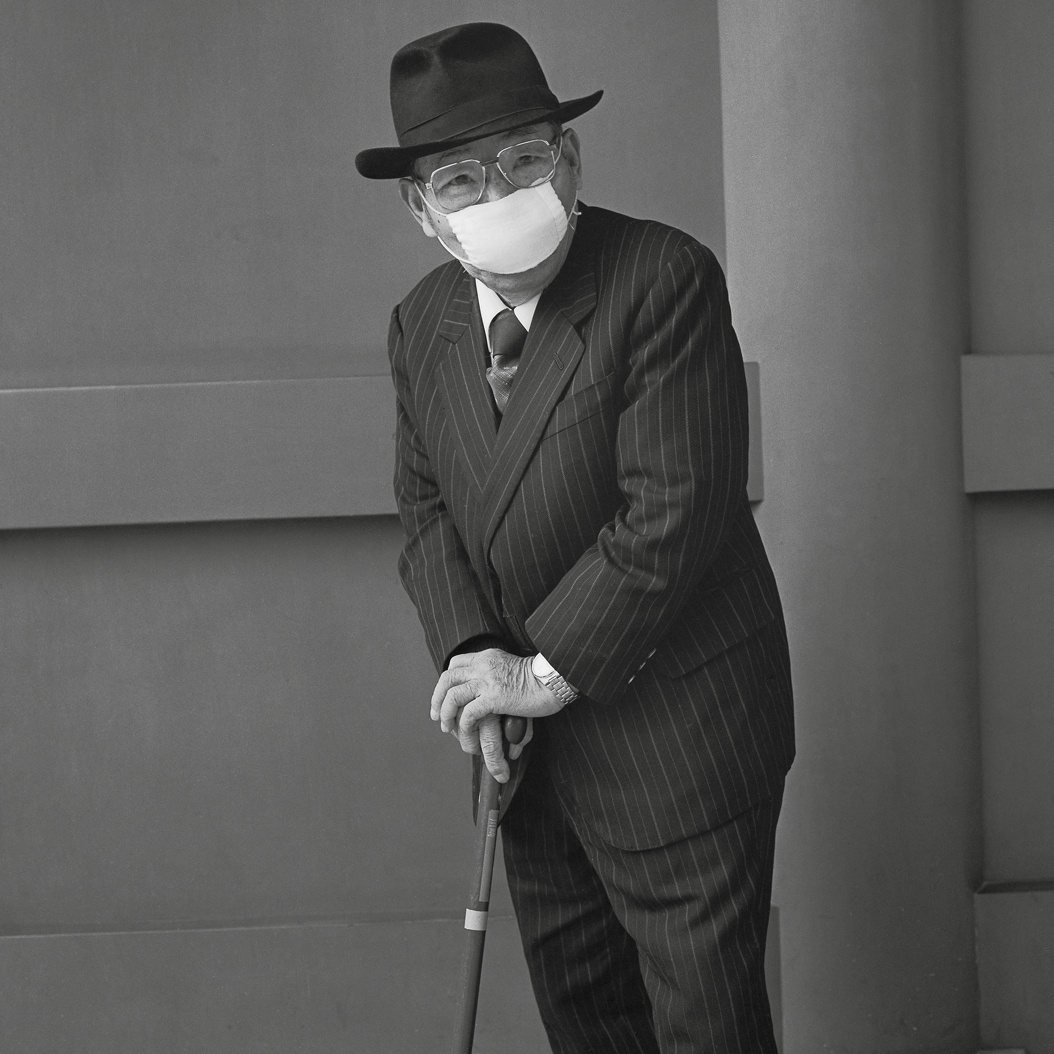

An Old Man With a Penetrating Gaze, from the series Asakusa Portraits, by Hiroh Kikai, 2001. Gelatin silver print. © Hiroh Kikai, courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery.

To me, there seem only two lines of emergence from this dilemma. They are not mutually exclusive and might, in fact, supplement each other very well.

In the first place, Britain could be encouraged to proceed vigorously with her plans for participation in a European union, and we could try to bring that entire union, rather than just Britain alone, into a closer economic association with this country and Canada.

A second possible solution would be in arrangements whereby a union of Western European nations would undertake jointly the economic development and exploitation of the colonial and dependent areas of the African continent. The realization of such a program admittedly presents demands which are probably well above the vision and strengths and leadership capacity of present governments in Western Europe. It would take considerable prodding from outside and much patience. But the idea itself has much to recommend it. The African continent is relatively little exposed to communist pressures; and most of it is not today a subject of great power rivalries. It lies easily accessible to the maritime nations of Western Europe, and politically they control or influence most of it. Its resources are still relatively undeveloped. It could absorb great numbers of people and a great deal of Europe’s surplus technical and administrative energy. Finally, it would lend to the idea of Western European union that tangible objective for which everyone has been rather unsuccessfully groping in recent months.

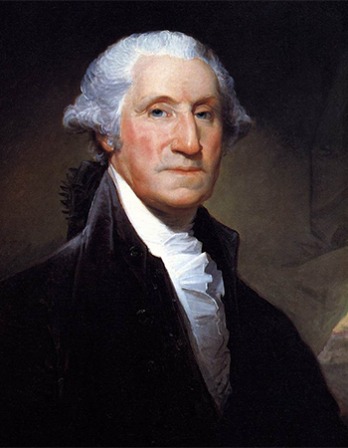

From a top-secret report written for Secretary of State George Marshall. In 1933 Kennan was charged with reopening the U.S. embassy in Moscow, closed since the Russian Revolution, and after assignments in Prague, Berlin, and Lisbon he returned to Moscow in 1944. Two years later he sent the highly influential so-called Long Telegram to Marshall, stating that U.S. and Soviet interests were incompatible and that containment of Soviet power was essential. Kennan was soon made director of policy planning and helped develop the Marshall Plan.

Back to Issue