If fear is associated with the expectation that something destructive will happen to us, plainly nobody will be afraid who believes nothing can happen to him.

We shall not fear things that we believe cannot happen to us, nor people who we believe cannot inflict them on us. It follows therefore that fear is felt by those who believe something to be likely to happen to them, at the hands of particular persons, in a particular form, and at a particular time. People do not believe this when they are, or think they are, in the midst of great prosperity, and are in consequence insolent, contemptuous, and reckless—the kind of character produced by wealth, physical strength, abundance of friends, power; nor yet when they feel they have experienced every kind of horror and have grown callous about the future—like men who are being flogged and are already nearly dead. If they are to feel the anguish of uncertainty, there must be some faint expectation of escape. This appears from the fact that fear sets us thinking what can be done, which of course nobody does when things are hopeless.

Having seen the nature of fear, and of the things that cause it, and the various states of mind in which it is felt, we can also see what confidence is, about what things we feel it, and under what conditions. It is the opposite of fear, and what causes it is the opposite of what causes fear. It is therefore the expectation associated with a mental picture of the nearness of what keeps us safe, and the absence or remoteness of what is terrible. It may be due either to the near presence of what inspires confidence or to the absence of what causes alarm. We feel it if we can take steps—many, or important, or both—to cure or prevent trouble; if we have neither wronged others nor been wronged by them; if we have either no rivals at all or no strong ones; if our rivals who are strong are our friends or have treated us well or been treated well by us; or if those whose interest is the same as ours are the more numerous party, or the stronger, or both.

There are two reasons why human beings face danger calmly: they may have no experience of it or they may have means to deal with it. Thus, when in danger at sea, people may feel confident about what will happen either because they have no experience of bad weather or their experience gives them the means of dealing with it. We also feel confident whenever there is nothing to terrify other people like ourselves, or people weaker than ourselves, or people than whom we believe ourselves to be stronger—and we believe this if we have conquered them, or conquered others who are as strong as they are, or stronger. Also if we believe ourselves superior to our rivals in the number and importance of the advantages that make men formidable—wealth, physical strength, strong bodies of supporters, extensive territory, and the possession of all, or the most important, appliances of war. Also if we have wronged no one, or not many, or not those of whom we are afraid; and generally, if our relations with the gods are satisfactory, as will be shown especially by signs and oracles. The fact is that anger makes us confident—that anger is excited by our knowledge that we are not the wrongers but the wronged, and that the divine power is always supposed to be on the side of the wronged. Also when, at the outset of an enterprise, we believe that we cannot and shall not fail, or that we shall succeed completely.

From the Rhetoric. This examination of fear is part of the philosopher’s study of the power of emotion in persuasion. “The person who carries fearlessness too far has no distinctive name,” he writes in his Nicomachean Ethics, “but if he were afraid of nothing—not even of an earthquake or inundation, as they say of the Celts—he would be a maniac or insensate.” On the other hand, the “man who exceeds in fearing is a coward. He fears the wrong things and in the wrong way.”

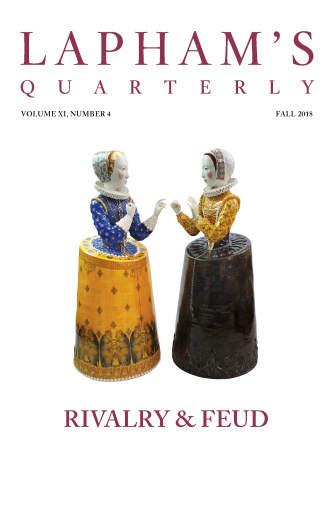

Back to Issue