Worry over what has not occurred is a serious malady.

—Solomon ibn Gabirol, 1050

Medusa’s head depicted on a mosaic floor in a tepidarium of the Roman era. Museum of Sousse, Tunisia.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

The ancient Greeks were connoisseurs of fear. The Greek language offered wide-ranging terminology to calibrate different shades and effects: déos, straightforward terror, fear, or apprehension; phóbos, fear that impels panic and battle rout; ekplektos, shock that strikes one dumb. Fear can be krúoeis, chilling, freezing, numbing; or smerdaléos, a huge and terrifying adjective—in origin it appears to have been a dreadful sound, such as the crushing of bones or gnashing of teeth, and is used of the thunder of Zeus. Fear turns warriors green, jabbers their teeth, trembles their limbs. It can be deinós, dread or awe-inspiring, a term used frequently of gods, and a feeble echo of which is captured in our dinosaur—the dread lizard. One terrible object, however, conjured every attribute of fear and every shade of meaning, and this was the head of the monstrous Gorgon, a mere glance at which turned men to stone.

The Gorgon is evoked in a variety of literature and above all in art. Images of the Gorgon head, or Gorgoneion, appear from the seventh century BC onward on painted vases, as architectural features, and on coins. In mythology, the Gorgons were three sisters, Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa. Along with other monstrous offspring that included Echidna (Viper) and Ophis (Serpent), the Gorgons were the result of an incestuous union between children of Pontos (Sea) and Gaia (Earth). The source for this genealogy is the Greek poet Hesiod, whose Theogony, written in the seventh century BC, is the basis of much mythological knowledge. For reasons Hesiod does not explore, the first two Gorgons were divine, while Medusa was wholly mortal. Other early poets add further details: the Gorgons lived in the far west, toward the edge of night, on a rocky island beyond the streams of all-encircling Ocean. Little is given in the way of physical description except to note that they wore snakes wrapped about their waists, and that the face of Medusa turned men to stone.

It is the story of Medusa’s head, however, that rivets attention. Central to this story is the hero Perseus, a prince of Argos, an actual city of great antiquity that once commanded much of the Peloponnese; his association with other named cities of the Argolid, such as Mycenae and Tiryns, has led some to believe there may have been a historical king behind the myth. In mythology, Perseus is the son of beautiful Danaë, whose own father locked her away in a bronze chamber in order to outwit a prophecy that any son she bore would kill him. Zeus, however, assuming the form of a shower of golden light, infiltrated the chamber and impregnated her. When Danaë gave birth to Perseus, her father put mother and child into a chest and set them adrift upon the sea. An island fisherman of noble blood rescued them, and they remained with their savior on the island. When Perseus came of age, he was invited to a birthday celebration at the court of the local king, who happened to be the fisherman’s brother. Asked what gift he would bring for the occasion, Perseus replied, rashly and inexplicably, “the Gorgon’s head.” When the king held him to his answer, Perseus’ adventures began.

Stock elements from folklore confuse the tale. Perseus must conquer other dreadful creatures, who hold key information to his quest. Nymphs give him magic gifts—winged sandals, a cap of darkness, a bag to hold the Gorgon’s head. The divine patrons Hermes and Athena instruct him to avoid the Gorgon’s petrifying gaze by averting his eyes, and in some versions of the story he uses his polished shield as a mirror to go about his work. When Perseus finds the Gorgon sisters they are sleeping.

As he strikes off Medusa’s head with his sword, two creatures are born from her bloodied neck: an undistinguished warrior named Chrysaor, who (as his Greek name suggests) possessed a golden sword; and, more impressively, the winged horse Pegasus. The two surviving Gorgons give pursuit, but aided by his magic gifts, Perseus escapes to other adventures that include rescuing the Ethiopian princess Andromeda from a sea monster and using the head of the dead Medusa to turn his enemies to stone. Finally, to adorn her fearsome panoply, Athena sets the Gorgon head on either her breastplate or the aegis, the latter being an enigmatic icon of terror and power possessed by Zeus but loaned occasionally to other gods.

It is an odd story, and all its details do not seem to belong to the same narrative. Perseus’ elaborate magic gifts, for example, are not essential, given that he finds and kills Medusa while she and her sisters are sleeping and that he enjoys the protection of two powerful divinities to elude capture. No explanation is given for what inspired Perseus to offer the Gorgon head in the first place—no aspect of the tangled story suggests any previous connection between him and them. And why kill her at all if she is living at a safe remove by the distant shores of Ocean?

A weak explanation for the killing is given in a work traditionally ascribed to Apollodorus, which although composed as late as the first or second centuries, draws from the writings of Pherecydes, a mythologist of the fifth century BC. According to this work, “Medusa alone was mortal; for that reason Perseus was sent to fetch her head.” In other words, the reason to kill her was that she could be killed. The author adds, however, and seems to be quoting a second source, “it is alleged by some that Medusa was beheaded for Athena’s sake; and they say that the Gorgon was fain to match herself with the goddess even in beauty.” The jealousy of gods and goddesses was notorious, and mortals who dared to compare themselves with their immortal betters were variously turned to stone, saw their children killed, were flayed alive, or drew undying hatred down upon their race, to cite just a few cases. Still, the warrior goddess Athena is not a usual candidate for purely feminine jealousy. Some scholars have speculated that this feminization of Medusa was inspired by a desire to make more credible—or palatable—Hesiod’s assertion that she was the mother of Pegasus by Poseidon, who lay with her “in a soft meadow amid spring flowers.” More likely, however, as Socrates believed, “such explanations are...the inventions of a very clever and laborious and not altogether enviable man,” who “must explain the forms of the Centaurs, and then that of the Chimera, and there presses in on him a whole crowd of such creatures, Gorgons and Pegasus.”

The earliest images of the Gorgon, found on reliefs and painted vases, depict a disembodied head with staring eyes and a fat tongue protruding from a gaping mouth. The face is fringed with tight curls and very often—and importantly—a beard. On vase paintings, the Gorgoneion often serves as the central embellishment of a warrior’s shield. Remarkably, whether painted or sculpted, the Gorgon face is always shown face forward, staring at the viewer head-on—a striking fact given the Greek convention for depicting characters, human and divine, in profile.

Eventually, the Gorgons acquired bodies, but the uneven variety of these suggests that early artists were traveling blind and that the stories that guided them described only the Gorgon head: one image even shows Medusa with a horse’s body. In all cases, whether the Gorgons are embodied or not, emphasis is placed squarely on the head. When Medusa’s sisters are shown as complete Gorgons, possessed of heads and bodies and wings, giving chase to Perseus, their striding legs and pumping arms appear in classic profile, but their Gorgon heads are turned to stare out at the viewer. In both painted and sculpted representations, the head is neckless, seemingly jammed, as though in afterthought, directly onto the creatures’ trunks.

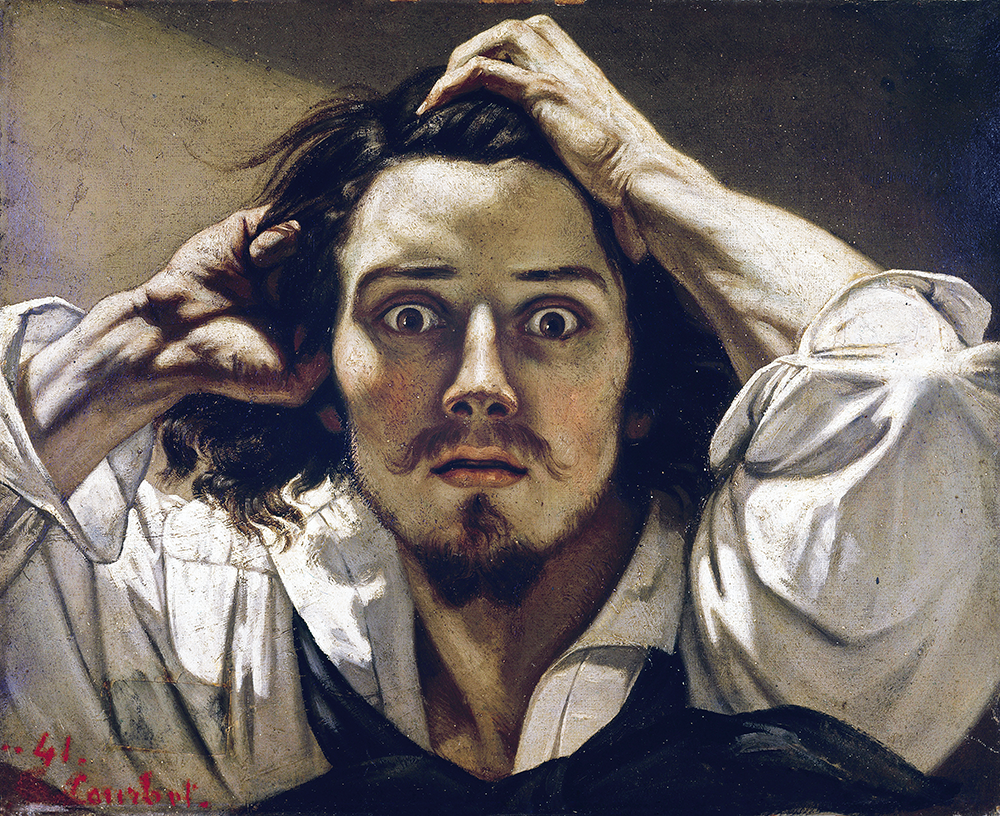

The Desperate Man, self-portrait by Gustave Courbet, 1843–45. © Luisa Ricciarini / Leemage / Bridgeman Images.

Over time, Medusa, if not her sister Gorgons, became less monstrous, more human, and specifically more feminine. By the late fifth century BC, Medusa has acquired a neck. After the fourth century BC, she is recognizably a woman, and is shown in conventional profile. Along the way she has also acquired her distinctive locks of snaky hair.

Although snakes were associated with Medusa from her earliest evocations—the Gorgons, after all, were sisters of Viper and Serpent—Medusa’s snake hair was for a long while only a tentative feature. It was the Roman poet Ovid, writing in the early first century, who gave the attribute currency. In his Metamorphoses, Ovid wildly embellishes Medusa’s story to accord with the romantic, titillating tenor of his poem. In his telling, Perseus, his ordeals behind him, relaxing with other nobles at a feast, is asked why Medusa, alone of the Gorgons, has snaky hair. “Because, O Stranger,” Perseus replies,

Beyond all others she

Was famed for beauty, and the envious hope

Of many suitors. Words would fail to tell the glory of her hair, most wonderful

Of all her charms—A friend declared to me

He saw its lovely splendor.

Medusa’s beauty attracted Poseidon, who, in the coy language of one nineteenth-century translator, “attained her love,” which is to say raped her, in the temple of the virgin goddess Athena. Athena, enraged by this violation of her purity, “turned her head away and held her shield before her eyes.” To punish the crime, she changed the Gorgon’s beautiful hair to serpents. Poseidon returns unscathed to the sea, and Athena places the Gorgon head upon her breastplate.

The Medusa’s story, in all its variety, has given rise to an extraordinary range of interpretations. Feminist scholars see the paralyzing force of Medusa’s head as a token of her rage, and the myth as a whole about the impulse to punish powerful women. Freudians, on the other hand, interpret the snakes as pubic hair, and the decapitation of this female creature as, somehow, signifying castration. “The sight of Medusa’s head makes the spectator stiff with terror, turns him to stone,” Freud wrote. “Becoming stiff means an erection. Thus in the original situation, it offers consolation to the spectator: he is still in possession of a penis.”

More straightforward theories scour mythologies of other lands. The Gorgon represents the evil eye, or the solar disk, or a monster that devours the sun. The fatal glare of the Gorgon head reflects the Semitic tradition of a god whose glory none can see and live. The Gorgon is the mother goddess who originates from the Assyrian snake demon, as represented by a bearded, snake-brandishing female appearing, for example, on a Luristan bronze. Also from Assyria is the story of Gilgamesh, whose exploits include taking the head of Humbaba, the terrifying god-appointed Guardian of the Cedar Forest, a creature depicted in art as a monstrous, grimacing head.

The essential features of the Gorgoneion—bulging eyes, grimacing face, protruding tongue—are shared by monstrous creatures of other cultures. The Indian Kirtimukha, or “Face of Glory,” for example, appears in painted and sculpted forms on temples, statues, and over entryways. Bes, the stocky dwarf god of ancient Egypt, shares many Gorgon traits, including a grotesque head with protruding tongue, a fringe of beard, and face-on presentation. The wide-staring face in the Aztec calendar stone, dating to about 1479, is also Gorgon-like in appearance.

Some explanations take inspiration from the natural world. The octopus, for example, has the appearance of a disembodied head with wide-staring eyes surrounded by snaky locks of hair. The Gorgon is a lionlike beast indigenous to the Libyan Desert. It is a thundercloud, a volcanic eruption, the ocean roar. Medusa’s origins lie in the Perseus constellation, whose blinking star evokes her “evil eye.” One theory speculates that grotesque clay masks were used as part of a ritual, possibly for young male initiates, at a cult to Perseus discovered at Mycenae.

All such explanations are based on certain features of the Gorgon head, but none accounts for all her traits, and many cite as evidence Gorgon features that are demonstrably late, such as the snakelike hair. To isolate the origin of the Gorgon’s petrifying terror, it is necessary to pare back centuries of accretions reflecting terrors peculiar to each passing age and stare down the original Gorgon—the grotesque, bulging-eyed, disembodied head.

The first evocation of the Gorgon head comes not from art but from literature. Hesiod, as we have seen, gives the parentage of the Gorgons in his Theogony, but his is not the earliest literary reference. That honor, as so many, lies with Homer, whose epic Iliad, dated to around 730–700 BC, describes the Gorgon in two telling passages.

The first occurs when the warrior goddess Athena prepares to enter the battle between Greeks and Trojans as it boils around the city of Troy. An unabashed champion of the Greeks, Athena girds herself to face her brother Ares, the murderous god of war, who is an ally to the Trojans.

And Athena, daughter of Zeus of the stormy aegis,

let fall her rippling robe upon her father’s floor,

elaborate with embroidery, which she herself had made and labored on with her own hands,

and putting on the cloak of Zeus who gathers clouds,

she armed herself for tearful war. Around her shoulders she flung the tasseled stormy aegis,

a thing of terror, crowned on every side with Panic all around,

and Strife was on it, and Attack, and chilling Flight,

and on it too the terrible monstrous Gorgon head,

a thing of awe and terror, portent of Zeus of the stormy aegis.

The Gorgoneion makes a second Iliadic appearance in an extended bravura description of another arming scene, that of Agamemnon, leader of the Achaeans and Argives, as Homer calls the Greeks.

Then he took up his man-surrounding, much-emblazoned forceful shield,

a thing of beauty, around which ran ten rings of bronze,

and on it twenty pale-shining disks of tin,

and in the very center was one of dark enameled blue.

And crowning this a bristling Gorgon face

stared out with dreadful glare, and Fear and Flight about her;

and the shield’s baldric was of silver, and on it

a blue-dark serpent writhed, with three heads

turned in all directions, growing from a single neck.

The function of the Gorgon head on the panoply of the warrior goddess and king of men is clear. Both carry it to arouse Fear and Flight and the swirl of such emotions as undo even courageous men in battle. For a mortal like Agamemnon, the Gorgoneion bolsters the protective attributes of his man-surrounding shield. Its purpose is apotropaic—meaning, in its original sense, “to turn away.” It serves as a protective talisman by frightening off, or averting, dangerous forces. In blunt purpose, then, the Gorgoneion is in the same category as gargoyles and scarecrows; in later centuries, it was in fact used on tiled roofs and temple structures to frighten off birds.

Illustration from an 1890 edition of Kyosai’s Pictures of One Hundred Demons, by Kawanabe Kyosai. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Mary and James G. Wallach Foundation Gift, 2013.

Yet while the function of the Gorgon head is straightforward, the question still begging is why the object is effective. Greek mythology claimed a menagerie of outlandish monsters: the fire-breathing Chimera; Scylla with her six necks; Cerberus, the many-headed hound guarding the gates of Hades. Why would the bloated face of the Gorgoneion be a more appropriate emblem for a warrior’s shield than, say, snarling Cerberus, monstrous keeper of the very gates of hell?

In a wide-ranging study of the Gorgon head, scholar Stephen Wilk was riveted by a forensic textbook’s description of the physical transformation undergone by a dead human body over the course of several days. Gases cause tissues to swell, “the eyes bulge and the tongue protrudes.” Forensic photographs reveal that even hair undergoes a change, rising in strange coils and rings around the bloated face. From all the manifold images traditionally marshaled, none so dreadfully resembles the Gorgon head as the face of human death.

Battlefields are never pretty sights—not in poetry, not in mythology, and certainly not in real life. Agamemnon’s arming scene, as a poetic case in point, is the prelude to one of the Iliad’s most savage battle sequences. In the ensuing rampage, Agamemnon smites off a warrior’s hands, then his neck, then sends the maimed trunk rolling like a log through the battle throng. As he rages like “obliterating fire” through the enemy lines, screaming, his invincible hands spattered with gore, “the heads fell of fleeing Trojans.”

Heads are rolled in the course of casual slaughter, and sometimes, too, as acts of more calculated savagery. When the Greek hero Patroclus falls in battle, a bitter fight ensues between Greeks and Trojans for his body. The Trojan hero Hector, generally depicted as his country’s high-minded protector, begins to “drag at Patroclus, so as to cut his head from his shoulders with his sharp bronze sword, / and after hauling the corpse away, to give it to the Trojan dogs.”

Tell us your phobias and we will tell you what you are afraid of.

—Robert Benchley, 1935In warrior cultures throughout history, the taking of an enemy head stands as the supreme act of triumph. The single act achieves the total humiliation of the vanquished. More darkly, it effects the obliteration of his personhood, the instant transformation of a human being into an object of horror. Today, even in the twenty-first century, the acts of ISIS have poked at embers that we believed civilization had buried long ago to demonstrate the primal efficacy of this talisman of terror:

Peneleos drawing his sharp sword

drove it through the middle of the neck of Ilioneus, and struck to the ground

his head with its helmet; and still the heavy spear

was fixed in his eye. And holding it up like the head of a poppy

Peneleos flaunted it before the Trojans and spoke, vaunting:

“From me, oh Trojans, tell the beloved father

and the mother of haughty Ilioneus to wail in their halls...”

So he spoke; and a trembling beneath their limbs seized them all,

and each man looked about him, to see how he might escape sheer destruction.

If the Gorgoneion originally and unambiguously represented a severed human head, not only are its peculiar physical features convincingly explained, but also its striking presence on Athena’s war gear. Above all, this conjecture conjures the dread object’s power to petrify—to turn to stone—all who gaze upon it. Mythology and ritual often preserve, and even honor, the potency of dark acts that a historical people themselves repudiate. The most terrifying conceivable object, the Greeks well knew, was not a snake-haired monster of imagination, but the concrete work of human hands.