There is not much less vexation in the government of a private family than in the managing of an entire state.

—Michel de Montaigne, 1580Enabling a Divorce

Mary McCarthy unwittingly aids a separation.

Under Polly’s door was a letter for her. She picked it up, not daring to look at it, for she knew it would be from her ex-boyfriend Gus. She took off her coat and hung it up, washed her hands, watered her plants, lit a cigarette. Then, trembling, she tore open the letter. Inside was a single sheet of paper, a short letter, in handwriting. She did not look directly at it yet but put it on the table, glancing at it sidewise, as if it could tell her what it said without making her read it. The letter was from her father.

Dear Polly,

Your mother and I have decided to get a divorce. If it suits you, I would like to come to New York and live with you. That is, if you are not otherwise encumbered. I could make myself useful, do the shopping and cooking for you. We might look for a little flat together. Your mother will keep the farm. My mental health is excellent.

Your obedient servant and loving father,

Henry L. K. Andrews

On hearing the news, everyone took for granted that her parents’ separation must have been a dreadful shock to her, but the sad truth was that all Polly felt then was a wan gratitude that her father was coming. It was with a start finally that she remembered her mother and wondered how she was taking it.

Long afterward, Polly admitted that it had all worked out for the best. She was happy, living with her father, far happier than she had been with Gus. They suited each other. And his arrival, three days after his letter, was occupational therapy for her—just what a doctor would have prescribed.

Mr. Andrews himself, when he got off the train, was in fine fettle—a small white-haired old man with a goblin head and bright blue eyes; he was carrying a case of fresh farm eggs, which he would not entrust to the redcap, and a bouquet of jonquils. He had not been so well in years, he declared, and Kate was well too, never better. He attributed it all to divorce—a splendid institution. Everyone should get a divorce. Kate already looked ten years younger. “But won’t it take a long time, Father?” said Polly. “All the legal side. Even if Mother consents.” But Mr. Andrews was sanguine. “Kate’s already filed the papers and served me. The process server came to tea. I’ve given her grounds, the best grounds there are.” Polly was slightly shocked at the notion that her father, at his age, had been committing adultery. But he meant insanity. He was delighted with himself for having had the foresight to be loony and to have the papers to prove it.

Low-spirited as she was during the first days, Polly was amused by her father. She was startled to hear herself laugh aloud the night he came; it was as if the sound had come from someone else. She told herself that she was going through the motions of living, now that she had someone to live for, but before long she found she was looking forward to coming home from work, wondering what they would have for dinner and what her father had been up to in her absence. He was immensely proud of the divorce and talked about it to everyone, as if it were some new process he had discovered, all by himself. For the time being, Polly had taken for him a room on the third floor; on weekends, they were going to look for an apartment. But then Mr. Andrews had a better idea. Having made friends with the landlady, he persuaded her to turn the top-floor rooms into an apartment for him and Polly—the lodger in the one that was rented could move downstairs to Polly’s place. He designed the new apartment himself, using the hall to gain space and to make a little kitchen, long and narrow, like a ship’s galley. All spring and early summer he and Polly were busy with the remodeling, which did not cost the landlady very much since Mr. Andrews gave his services free, did some of the carpentry himself (he had learned at the workshop in the sanatorium), and found a secondhand sink and plumbing fixtures in the junkyards he haunted, looking for treasure. Polly learned to paint, well enough to do the bookshelves and cupboards; she sewed curtains from old sheets, with a blue and red border, the colors of the French flag, and she got to work with upholstery tacks and recovered two of the landlady’s Victorian chairs.

The apartment, when it was finished, was delightful, with its old marble fireplaces and inside shutters; if Mr. Andrews and Polly were ever to leave it, the landlady could rent it for much more than she was charging them. Carried away with his success, Mr. Andrews wanted to redo the whole house into apartments and make the landlady’s fortune—a project Polly vetoed. Mr. Andrews had to content himself with the plan of making Polly a little winter garden or greenhouse for her plants, outside the back windows, which had a southern exposure; he wanted this to be Polly’s Christmas present and spent a good deal of his time at the glazier’s.

The change in Mr. Andrews amazed everyone who knew him. It could not be just the divorce, his sister Julia said, nor dear Polly’s good heart and youthful spirits. Something else must have happened to Henry. It was Polly’s mother who provided the information, during a visit she made to New York, where she stayed with her ex-sister-in-law on Park Avenue. “They changed the name of his illness, did you know that, Polly? They don’t call it melancholia any more. They call it manic-depressive psychosis. When Henry heard that, he felt as if he’d been cheated all these years. He’d only had the ‘depressed’ phase, you see. He cheered up extraordinarily and began to make all these projects. Beginning with the crazy notion that we ought to get a divorce. At first I went along with it just to humor him. You know, the way I did when he insisted on being baptized into the Roman faith by the village curé and then baptized all you children himself. I knew those baptisms were otiose, since you’d all been christened as infants in the Episcopal church. Well, I assumed the divorce bug would pass, like the Romanism bug. But he got more and more set on it and on coming to New York. So I finally said to myself, ‘Why not? Henry may have a good idea, after all. At our time of life, there’s no earthly reason to stay together if we don’t feel like it.’ And I’ve been a new woman myself ever since.” Polly looked at her mother, pouring tea at Aunt Julia’s table. It was true; she was blooming, like an expansive widow, and she had had a new permanent wave. “Excuse me, madam,” said Ross, who was passing biscuits, “but why couldn’t you and Mr. Henry just live apart, the way so many couples do?” “Henry said that wouldn’t be respectable,” replied Mrs. Andrews. “It would be like living together without marriage—living apart without a divorce.” “I see,” said Ross. “I never thought of it that way.” She gave Polly a wink. “I can run the farm much better myself,” Mrs. Andrews went on to Polly, lighting a cigarette and oblivious of Polly’s blush. “With just your brothers’ help. Henry was always interfering, and he’s never cared for domestic animals. He was only interested in his pot herbs and his kitchen garden. Now that he’s gone, we’ve bought some Black Angus and I’m going to try turkeys for the Thanksgiving market—I’ve been to see Charles & Company and they took an order. If Henry were there, he’d insist on Chinese pheasants or peacocks. And peacocks are such an unpleasant bird! Quarrelsome and shrill.”

© 1963 by Mary McCarthy, renewed 1991 by James Raymond West. Used with permission of the Mary McCarthy Literary Trust.

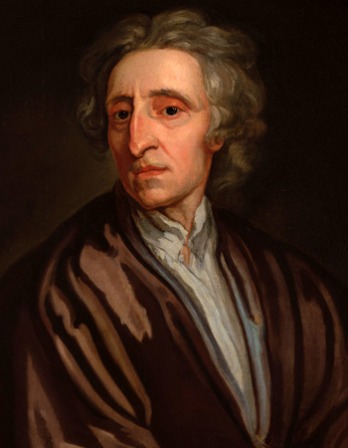

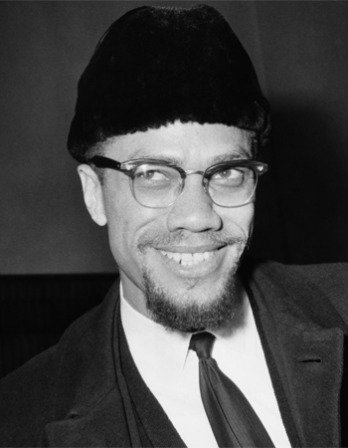

Mary McCarthy

From The Group. McCarthy was orphaned at the age of six after her parents were killed by the influenza epidemic of 1918, living first with relatives in Minnesota and then with her grandparents in Seattle. Attending Vassar College at the same time as Elizabeth Bishop, she graduated in 1933 and soon began writing for The New Republic and The Nation. McCarthy published her first work of fiction, The Company She Keeps, in 1942, her autobiography, Memories of a Catholic Girlhood, in 1957, and The Group in 1963.