Democracy cannot be static. Whatever is static is dead.

—Eleanor Roosevelt, 1942Minority Rule

W.E.B. Du Bois on the evil that the privileged may exercise.

What is the cause of the undoubted reaction and alarm that the citizens of democracy continually feel?

It is, I am sure, the failure to feel the full significance of the change of rule from a privileged minority to that of an omnipotent majority, and the assumption that mere majority rule is the last word of government; that majorities have no responsibilities, that they rule by the grace of God. Granted that government should be based on the consent of the governed, does the consent of a majority at any particular time adequately express the consent of all? Has the minority, even though a small and unpopular and unfashionable minority, no right to respectful consideration?

I remember that excellent little high school textbook, Nordhoff’s Politics, where I first read of government, saying this sentence at the beginning of its most important chapter: “The first duty of a minority is to become a majority.” This is a statement that has its underlying truth, but it also has its dangerous falsehood, viz., any minority that cannot become a majority is not worthy of any consideration. But suppose that the outvoted minority is necessarily always a minority? Women, for instance, can seldom expect to be a majority; artists must always be the few; ability is always rare; and black folk in this land are but a tenth. Yet to tyrannize over such minorities, to browbeat and insult them, to call that government a democracy which makes majority votes an excuse for crushing ideas and individuality and self-development, is manifestly a peculiarly dangerous perversion of the real democratic ideal. It is right here, in its method and not in its object, that democracy in America and elsewhere has so often failed. We have attempted to enthrone any chance majority and make it rule by divine right. We have kicked and cursed minorities as upstarts and usurpers when their sole offense lay in not having ideas or hair like ours. Efficiency, ability, and genius found often no abiding place in such a soil as this. Small wonder that revolt has come and high-handed methods are rife, of pretending that policies which we favor or persons that we like have the anointment of a purely imaginary majority vote.

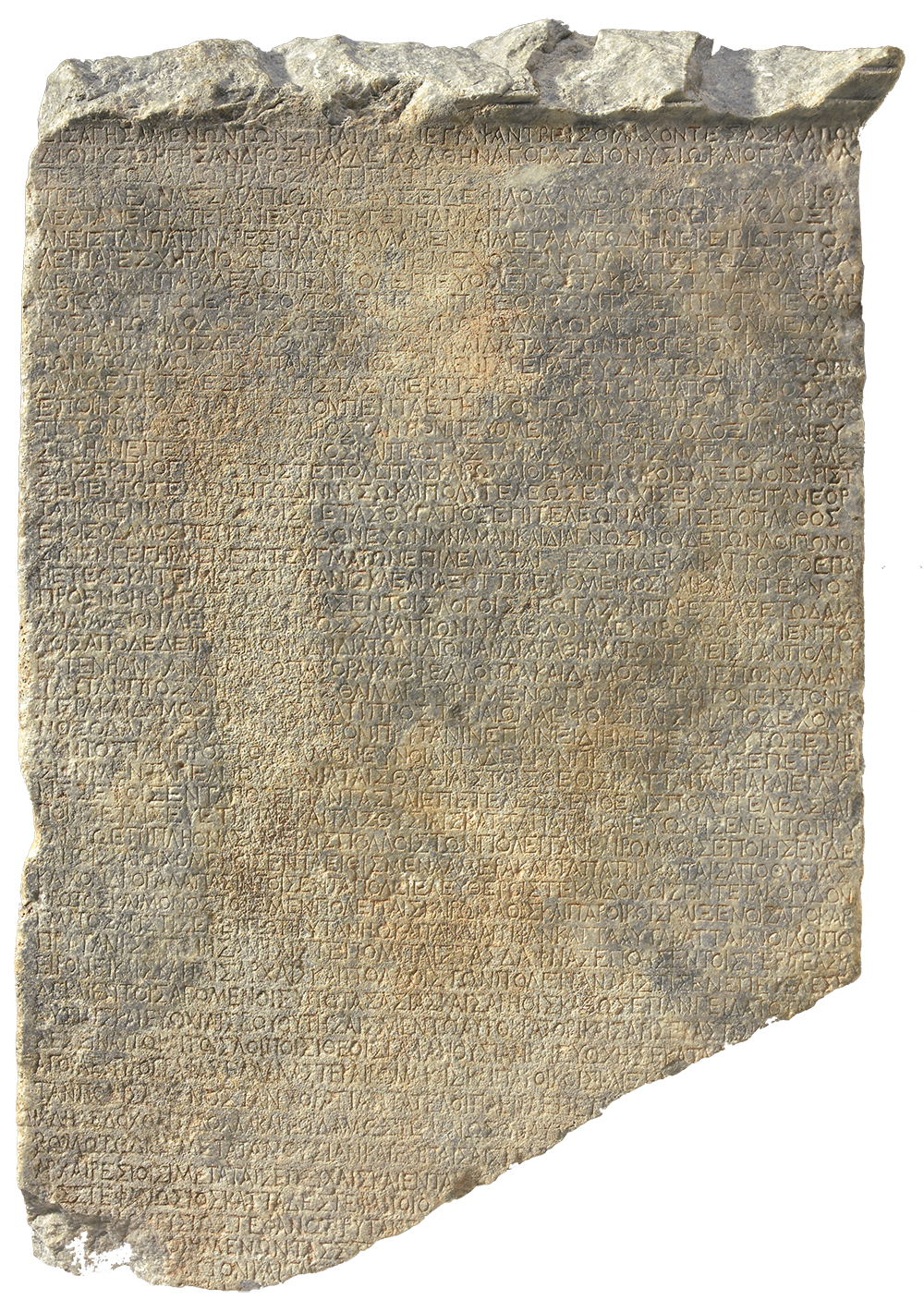

Stela honoring the magistrate and patron Kleanax, Kyme, Aeolis, late first century bc. © The J. Paul Getty Museum, digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Are the methods of such a revolt wise, howsoever great the provocation and evil may be? If the absolute monarchy of majorities is galling and inefficient, is it any more inefficient than the absolute monarchy of individuals or privileged classes have been found to be in the past? Is the appeal from a numerous-minded despot to a smaller, privileged group or to one man likely to remedy matters permanently? Shall we step backward a thousand years because our present problem is baffling?

Surely not and surely, too, the remedy for absolutism lies in calling these same minorities to council. As the king-in-council succeeded the king by the grace of God, so in future democracies the toleration and encouragement of minorities and the willingness to consider as “men” the crankiest, humblest, and poorest and blackest peoples must be the real key to the consent of the governed. Peoples and governments will not in the future assume that because they have the brute power to enforce momentarily dominant ideas, it is best to do so without thoughtful conference with the ideas of smaller groups and individuals. Proportionate representation in physical and spiritual form must come.

That this method is virtually coming in vogue we can see by the minority groups of modern legislatures. Instead of the artificial attempts to divide all possible ideas and plans between two great parties, modern legislatures in advanced nations tend to develop smaller and smaller minority groups, while government is carried on by temporary coalitions. For a time we inveighed against this and sought to consider it a perversion of the only possible method of practical democracy. Today we are gradually coming to realize that government by temporary coalition of small and diverse groups may easily become the most efficient method of expressing the will of man and of setting the human soul free. The only hindrance to the faster development of this government by allied minorities is the fear of external war that is used again and again to melt these living, human, thinking groups into inhuman, thoughtless, and murdering machines.

The persons, then, who come forward in the dawn of the twentieth century to help in the ruling of men must come with the firm conviction that no nation, race, or sex has a monopoly of ability or ideas; that no human group is so small as to deserve to be ignored as a part, and as an integral and respected part, of the mass of men; that above all no group of twelve million black folk, even though they are at the physical mercy of a hundred million white majority, can be deprived of a voice in their government and of the right to self-development without a blow at the very foundations of all democracy and all human uplift; that the very criticism aimed today at universal suffrage is in reality a demand for power on the part of consciously efficient minorities—but these minorities face a fatal blunder when they assume that less democracy will give them and their kind greater efficiency. However desperate the temptation, no modern nation can shut the gates of opportunity in the face of its women, its peasants, its laborers, or its socially damned. How astounded the future world citizen will be to know that as late as 1918 great and civilized nations were making desperate endeavor to confine the development of ability and individuality to one sex—that is, to one-half of the nation; and he will probably learn that similar effort to confine humanity to one race lasted a hundred years longer.

The doctrine of the divine right of majorities leads to almost humorous insistence on a dead level of mediocrity. It demands that all people be alike or that they be ostracized. At the same time, its greatest accusation against rebels is this same desire to be alike: the suffragette is accused of wanting to be a man, the socialist is accused of envy of the rich, and the black man is accused of wanting to be white. That any one of these should simply want to be himself is to the average worshipper of the majority inconceivable, and yet of all worlds, may the good Lord deliver us from a world where everybody looks like his neighbor and thinks like his neighbor and is like his neighbor.

The world has long since awakened to a realization of the evil that a privileged few may exercise over the majority of a nation. So vividly has this truth been brought home to us that we have lightly assumed that a privileged and enfranchised majority cannot equally harm a nation. Insane, wicked, and wasteful as the tyranny of the few over the many may be, it is not more dangerous than the tyranny of the many over the few. Brutal physical revolution can, and usually does, end the tyranny of the few. But the spiritual losses from suppressed minorities may be vast and fatal and yet all unknown and unrealized because idea and dream and ability are paralyzed by brute force.

W.E.B. Du Bois

From “Of the Ruling of Men.” Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, in 1868, the historian, activist, and cofounder of the NAACP died in Ghana in 1963, one day before the March on Washington, where he was honored with a moment of silence. “The effort of the Negro during Reconstruction to become an integral part of modern democracy was one of the greatest steps that democracy has taken in the modern world,” he wrote in 1943. “By every standard their efforts…deserved reward and recognition, but did not receive it.”