We and the dead ride quick at night.

—Gottfried August Bürger, 1773Examining the Cadavers

Mary Roach visits a decay facility.

Out behind the University of Tennessee Medical Center is a lovely forested grove with squirrels leaping in the branches of hickory trees and birds calling and patches of green grass where people lie on their backs in the sun, or sometimes the shade, depending on where the researchers put them.

This pleasant hillside is a field-research facility, the only one in the world dedicated to the study of human decay. The people lying in the sun are dead. They are donated cadavers, helping, in their mute, fragrant way, to advance the science of criminal forensics. For the more you know about how dead bodies decay—the biological and chemical phases they go through, how long each phase lasts, how the environment affects these phases—the better equipped you are to figure out when any given body died: in other words, the day and even the approximate time of day it was murdered. The police are pretty good at pinpointing approximate time of death in recently dispatched bodies. The potassium level of the gel inside the eyes is helpful during the first twenty-four hours, as is algor mortis—the cooling of a dead body; barring temperature extremes, corpses lose about 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit per hour until they reach the temperature of the air around them. (Rigor mortis is more variable: it starts a few hours after death, usually in the head and neck, and continues, moving on down the body, finishing up and disappearing anywhere from ten to forty-eight hours after death.)

If a body has been dead longer than three days, investigators turn to entomological clues (e.g., how old are these fly larvae?) and stages of decay for their answers. And decay is highly dependent on environmental and situational factors. What’s the weather been like? Was the body buried? In what? Seeking better understanding of the effects of these factors, the University of Tennessee (UT) Anthropological Research Facility, as it is blandly and vaguely called, has buried bodies in shallow graves, encased them in concrete, left them in car trunks and man-made ponds, and wrapped them in plastic bags. Pretty much anything a killer might do to dispose of a dead body the researchers at UT have done also.

To understand how these variables affect the timeline of decomposition, you must be intimately acquainted with your control scenario: basic, unadulterated human decay. That’s why I’m here. That’s what I want to know: When you let nature take its course, just exactly what course does it take?

My guide to the world of human disassembly is a patient, amiable man named Arpad Vass. Arpad has studied the science of human decomposition for more than a decade. He is an adjunct research professor of forensic anthropology at UT and a senior staff scientist at the nearby Oak Ridge National Laboratory. One of Arpad’s projects at ORNL has been to develop a method of pinpointing time of death by analyzing tissue samples from the victim’s organs and measuring the amounts of dozens of different time-dependent decay chemicals. This profile of decay chemicals is then matched against the typical profiles for that tissue for each passing postmortem hour. In test runs, Arpad’s method has determined the time of death to within plus or minus twelve hours.

The samples he used to establish the various chemical-breakdown timelines came from bodies at the decay facility. Eighteen bodies, some seven hundred samples in all. It was an unspeakable task, particularly in the later stages of decomposition, and particularly for certain organs. “We’d have to roll the bodies over to get at the liver,” recalls Arpad. The brain he got to using a probe through the eye orbit. Interestingly, neither of these activities was responsible for Arpad’s closest brush with on-the-job regurgitation. “One day last summer,” he says weakly, “I inhaled a fly. I could feel it buzzing down my throat.”

I have asked Arpad what it’s like to do this sort of work. “What do you mean?” he asked me back. “You want a vivid description of what’s going through my brain as I’m cutting through a liver and all these larvae are spilling out all over me and juice pops out of the intestines?” I kind of did, but I kept quiet. He went on: “I don’t really focus on that. I try to focus on the value of the work. It takes the edge off the grotesqueness.” As for the humanness of his specimens, that no longer disturbs him. Though it once did. He used to lay the bodies on their stomachs so he didn’t have to see their faces.

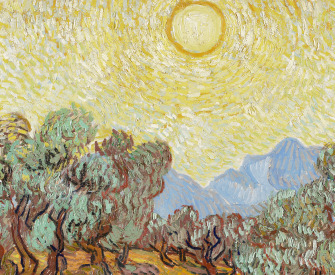

The Space Between Now and Pangaea Ultima, by Mary Mattingly, 2007. © Mary Mattingly, courtesy Robert Mann Gallery.

This morning, Arpad and I are riding in the back of a van being driven by the lovable and agreeable Ron Walli, one of ORNL’s media-relations guys. Ron pulls into a row of parking spaces at the far end of the UT Medical Center lot, labeled g section. On hot summer days you can always find a parking space in the G section, and not just because it’s a longer walk to the hospital. G section is bordered by a tall wooden fence topped with concertinaed wire, and on the other side of the fence are the bodies. Arpad steps down from the van. “Smell’s not that bad today,” he says.

“Let’s start over there.” Arpad is pointing to a large male figure about twenty feet distant. From this distance, he could be napping, though there is something in the lay of the arms and the stillness of him that suggests something more permanent.We walk toward the man. Ron stays near the gate, feigning interest in the construction details of a toolshed.

Like many big-bellied people in Tennessee, the dead man is dressed for comfort. He wears gray sweatpants and a single-pocket white T-shirt. Arpad explains that one of the graduate students is studying the effects of clothing on the decay process. Normally, they are naked.

The cadaver in the sweatpants is the newest arrival. He will be our poster man for the first stage of human decay, the “fresh” stage. (Fresh, as in fresh fish, not fresh air. As in recently dead but not necessarily something you want to put your nose right up to.) The hallmark of fresh-stage decay is a process called autolysis, or self-digestion. Human cells use enzymes to cleave molecules, breaking compounds down into things they can use. While a person is alive, the cells keep these enzymes in check, preventing them from breaking down the cells’ own walls. After death, the enzymes operate unchecked and begin eating through the cell structure, allowing the liquid inside to leak out.

“See the skin on his fingertips there?” says Arpad. Two of the dead man’s fingers are sheathed with what look like rubber fingertips of the sort worn by accountants and clerks. “The liquid from the cells gets between the layers of skin and loosens them. As that progresses, you see skin sloughage.” Mortuary types have a different name for this. They call it “skin slip.” Sometimes the skin of the entire hand will come off. Mortuary types don’t have a name for this, but forensics types do. It’s called “gloving.”

Men have written in the most convincing manner to prove that death is no evil, and this opinion has been confirmed on a thousand celebrated occasions by the weakest of men as well as by heroes. Even so I doubt whether any sensible person has ever believed it, and the trouble men take to convince others as well as themselves that they do shows clearly that it is no easy undertaking.

—La Rochefoucauld, 1665“As the process progresses, you see giant sheets of skin peeling off the body,” says Arpad. He pulls up the hem of the man’s shirt to see if, indeed, giant sheets are peeling. They are not, and that’s okay.

Something else is going on. Squirming grains of rice are crowded into the man’s belly button. It’s a rice-grain mosh pit. But rice grains do not move. These are young flies. Entomologists have a name for young flies, but it is an ugly name, an insult. Let’s not use the word maggot. Let’s use a pretty word. Let’s use hacienda.

Arpad explains that the flies lay their eggs on the body’s points of entry: the eyes, the mouth, open wounds, genitalia. Unlike older, larger haciendas, the little ones can’t eat through skin. I make the mistake of asking Arpad what the little haciendas are after.

Arpad walks around to the corpse’s left foot. It is bluish and the skin is transparent. “See the [haciendas] under the skin? They’re eating the subcutaneous fat. They love fat.” I see them. They are spaced out, moving slowly. It’s kind of beautiful, this man’s skin with these tiny white slivers embedded just beneath its surface. It looks like expensive Japanese rice paper. You tell yourself these things.

The digestive organs and the lungs disintegrate first, for they are home to the greatest numbers of bacteria; the larger your work crew, the faster the building comes down. The brain is another early departure organ. “Because all the bacteria in the mouth chew through the palate,” explains Arpad. And because brains are soft and easy to eat. “The brain liquefies very quickly. It just pours out the ears and bubbles out the mouth.”

Up until about three weeks, Arpad says, remnants of organs can still be identified. “After that, it becomes like a soup in there.” Because he knew I was going to ask, Arpad adds, “Chicken soup. It’s yellow.”

Muscles are eaten not only by bacteria but by carnivorous beetles. I wasn’t aware that meat-eating beetles existed, but there you go. Sometimes the skin gets eaten, sometimes not. Sometimes, depending on the weather, it dries out and mummifies, whereupon it is too tough for just about anyone’s taste. On our way out, Arpad shows us a skeleton with mummified skin, lying facedown. The skin has remained on the legs as far as the tops of the ankles. The torso, likewise, is covered, about up to the shoulder blades. The edge of the skin is curved, giving the appearance of a scooped neckline, as on a dancer’s leotard. Though naked, he seems dressed.

Death and the Maiden, by Egon Schiele, 1915. Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna, Austria.

We stand for a minute, looking at the man.

There is a passage in the Buddhist sutra on mindfulness called the Nine Cemetery Contemplations. Apprentice monks are instructed to meditate on a series of decomposing bodies in the charnel ground, starting with a body “swollen and blue and festering,” progressing to one “being eaten by…different kinds of worms,” and moving on to a skeleton, “without flesh and blood, held together by the tendons.” The monks were told to keep meditating until they were calm and a smile appeared on their faces. I describe this to Arpad and Ron, explaining that the idea is to come to peace with the transient nature of our bodily existence, to overcome the revulsion and fear. Or something.

We all stare at the man. Arpad swats at flies. “So,” says Ron. “Lunch?”

© 2003, Mary Roach. Used with permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. This selection may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means without prior written permission of the publisher.

Mary Roach

From Stiff: The Curious Life of Human Cadavers. The Greek physician Herophilus, born around 335 bc, was among the first known performers of public dissections of human cadavers. Roach begins this book with the following observation, “The way I see it, being dead is not terribly far off from being on a cruise ship. Most of your time is spent lying on your back. The brain has shut down. The flesh begins to soften. Nothing much new happens, and nothing is expected of you.” She is also the author of Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex.