Man punishes the action, but God the intention.

—Thomas Fuller, 1732

Orestes and Pylades Disputing at the Altar, by Pieter Lastman, 1614. Rijksmuseum, purchased with the support of the Vereniging Rembrandt.

When we look at the history of the world, it resembles nothing so much as a police blotter. Even the Bible is predominantly a record of crime and punishment, of sinfulness, large-scale and trivial, followed by rather Technicolor retribution—floods, plagues, ethnic cleansing, holocausts of every description. Similarly, our classical myths, so central to our Western culture, regularly chronicle acts of deicide, genocide, parenticide, and infanticide, as well as the more usual fleshly transgressions of incest, rape, and adultery. To the randy and contentious deities of Mount Olympus, the world is little more than a harem or an amusing global chessboard. Gloucester famously remarks in King Lear, “As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods. They kill us for their sport.”

Adam’s expulsion from Eden for disobeying what one might call God’s pomological commandment marks the beginning of Judeo-Christian history. In the classical world, a comparably important event also begins with an apple. When Paris awards the golden apple to Aphrodite in return for the favors of the lovely Helen, he sets in motion the major cataclysm of antiquity. The Trojan War initiated a conflict between West and East that was to continue throughout ancient times, to be celebrated in song and remembered as history. Those ancient hostilities are in some senses still with us.

Like the Bible, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey—bulked out with some now lost epics about the return home from Troy of the various Greek heroes—soon became sourcebooks for artists and poets, philosophers and theologians. Here were stories that could be used to hammer home arguments in the law courts, illustrate points of moral philosophy, or provide plots for some of the great tragic dramas.

Of these last, the greatest by far is Aeschylus’ three-part Oresteia, consisting of Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides. Considering its relative brevity, this trilogy constitutes a deeply affecting study of crime and punishment, probing such irresolvable and vexatious issues as the nature of justice, the frequent conflicts between love and duty, the torments of moral decision making, our obligations to the gods, society, and ourselves, and the spiritual consequences of irremediable actions. Above all, the Oresteia shows us the burdens of a culture based on the lex talionis—an eye for an eye—and the blessings of a jury trial in a court of law. After seemingly endless bloodletting—in just one family a man ritually sacrifices his child, a wife murders her husband, and a son executes his mother—there is a final cauterization, and the butchery stops for good. Quite literally for good. In every way, it is a foundational literary work for examining the crucial place of law in society.

The Hanged Man or John Brown, by Victor Hugo, 1860.

That said, the Oresteia’s widespread reputation for solemn grandeur may scare off some modern readers. Even Aristotle preferred Sophocles’ Oedipus the King as the ideal or model tragedy. On the surface Oedipus the King might seem a more attractive example of classical crime and punishment, indeed almost an instance of early detective fiction. Who killed Laertes? King Oedipus reopens this cold case and in due course discovers that the least likely suspect, the man who couldn’t possibly have committed the murder, is in fact the culprit—the investigator himself. Agatha Christie would be envious (and indeed would adopt a close variant of this solution in one of her most famous novels). Yet as wonderful as Oedipus the King is, it sometimes feels just as clockwork as a Christie, a carefully tooled piece of slick drama focusing largely on a single revelation and a single character. But compare it with the Agamemnon: while Sophocles’s play might be seen as a pièce bien faite, Aeschylus’ drama bursts from any stage that tries to contain it.

Just recounting the plot of the Oresteia suggests some of its complexity and troubling power.

The first play opens with a watchman in Argos awaiting a signal fire that will announce the end of the Trojan War and the imminent return of the victorious general, Agamemnon. But as the watchman complains about the long hours and the dew and the cold, he also hints that something is rotten in the city of Argos. When Agamemnon finally arrives home, brimming with pride and pomp (even though he’s lost most of his fleet), he brings with him booty of various kinds, including the prophetess Cassandra, now his concubine. At his palace door, he is lavishly welcomed by his apparently loving wife Clytemnestra—Helen’s half-sister—whose handmaidens have spread costly tapestries on the ground in his honor. At first, Agamemnon resists walking on the blood-red carpets, calling it an extravagant honor more appropriate to a god than a man, but eventually this self-important warrior yields to his wife’s shrewd blandishments. Once inside the house, though, the unsuspecting Agamemnon—naked and unarmed as he prepares to enter, or possibly leave, a purifying bath—is suddenly entrapped in a kind of netlike cloth. The duplicitous and adulterous Clytemnestra then brutally, exultantly hacks him to death. The murder is immediately followed by that of Cassandra, who had foreseen it all—though, as usual, nobody believed her frenzied, prophetic wailings. These two deaths accomplished, Clytemnestra reappears onstage with her lover, Agamemnon’s cousin Aegisthus, who has been essentially skulking in the wings. They will be the new rulers of Argos.

Why has Clytemnestra killed her husband? Her explanation points to a mother’s love for her daughter and hatred for that daughter’s killer. Ten years earlier, Agamemnon—at the insistence of the goddess Artemis—had sacrificed his child Iphigenia, so that the becalmed Greek fleet might be granted a favorable wind on which to sail to Troy. A good reason for murder, it might seem. But, as the poet Pindar wrote, there might be other reasons, too:

Pitiless woman. Was it Iphigeneia,

Slain at Euripos far from her land,

Who stung her to uplift

The wrath of her heavy hand?

Or was she broken in to a paramour’s bed

And the nightly loves

Turned her mind?

At least twice in these plays, Clytemnestra alludes to her sexual loneliness. “It is a cruel thing,” she says in Hugh Lloyd-Jones’ translation, “for wives to be separated from a husband.” Obviously, once involved with Aegisthus, her alienation from Agamemnon would have been exacerbated by her lover’s own long-abiding wish to see his cousin dead: years before, Agamemnon’s father killed all of Aegisthus’ brothers and then promptly served them in a stew to Aegisthus’ father. Little wonder the surviving son would want to exact retribution. Sexual jealousy, too, could have further fueled Clytemnestra’s rage: she might have heard about Agamemnon’s battlefield concubine Briseis—the reason for his quarrel with Achilles that opens the Iliad—and she has only to look out her front door to see his current sweetie Cassandra.

So many reasons to kill, and still the modern reader might speculate about one more: Clytemnestra is the most dominant character of the trilogy—steely and determined, possessed of a “manly” heart, and willing to act with dispatch and without regard for the consequences. After ten years she might well have grown used to having her own way and enjoying the comforts of an easily manipulated boy toy. Why, by all the gods, should she go back to playing the part of a meek housewife to an overweening lout?

Some years now pass before The Libation Bearers opens. Orestes, the son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, has grown up in exile and been commanded by Apollo to avenge his father’s murder. He is warned that if he fails to carry out this act of justice, even though it does require matricide, he will be sucked dry of his blood by the Erinyes (the Furies). As the play begins, Orestes and his friend Pylades are offering up prayers at Agamemnon’s grave when they are interrupted by a procession of mourners, among them Orestes’ sister Electra. These libation bearers have been sent by Clytemnestra, recently troubled by a fearful dream in which she suckled a snake that drew blood. Full of disquiet, she hopes that the proper funeral rituals and libations will help atone for her crime.

Instead, Electra and Orestes, reinforced by a solemn incantation that summons up the spiritual approval of Agamemnon, conspire at the destruction of their mother and her lover. In due course, Clytemnestra—convinced by two young “strangers” that her son is dead—unknowingly welcomes Orestes and Pylades into her house. First, the pair do away with Aegisthus. But when Clytemnestra’s turn comes, Orestes hesitates. His suppliant mother bares her breast and asks if he can murder the woman who gave him life. The young man appeals to his friend, “Pylades, what am I to do? Shall I respect my / mother and not kill her?” Then Pylades laconically answers, delivering his only lines of the play, “Where henceforth shall be the oracles of Loxias [Apollo] / declared at Pytho and the covenant you pledged on oath? / Count all man your enemies rather than the gods!” This sounds like good advice. Yet poor Orestes is, as he will soon discover, caught in a lose-lose situation. In the end, fearing to shirk his appointed duty, he leads away his now threatening mother, and the bloody deed is done.

The young man then finds himself surrounded by the harpy-like Erinyes, the very fate he had hoped to avoid. These snuffling, whining hags are tasked with pursuing those who have spilled the blood of their kindred. As is customary, just the horrid vision of the Erinyes drives their victim mad, and Orestes soon flees from Argos with these hellhounds on his trail. Modern readers readily, if anachronistically, interpret the Furies as nothing less than the visible manifestations of the pangs of conscience.

The last play in the trilogy, The Eumenides, follows Orestes to Athens, where the justice of his actions—and whether he should be punished for them—will be determined in a trial by jury. He will be defended by Apollo and prosecuted by the Erinyes, while Athena presides over the proceedings. This is more than melodrama. The scholar John Herington has described the trial scene as the acme of Aeschylean surrealism: “That a jury of human beings should sit to vote on a case that has divided the powers of Heaven and Earth, the attorneys for the prosecution being daughters of Night and nieces of Fate, while the defense counsel is a son of Zeus and his spokesman!”

Apollo argues that Zeus’ law requires a dutiful son to avenge the death of his father, even when the murderer is his own mother. He also points out that a man’s life is worth more than a woman’s: the father is the true parent, the mother merely the incubator of the child. The Erinyes maintain that since near the dawn of time, they have preserved the order of things by duly punishing those who have spilt the blood of their kindred. When the jury finally votes, the result is a tie and must be decided by Athena, who finds in favor of Apollo and Orestes. The furies immediately threaten reprisals for what they regard as an act of lèse-majesté. Athena with infinite tact gradually persuades these ancient goddesses that the Athenians will actually honor them far more than any other people, even setting up a special sanctuary in their honor nearby. The mollifed Furies agree and are given a new name—the Eumenides, that is, the Kindly Ones. The trilogy’s first audience in 458 bc would then have seen the Oresteia close on a scene of mutual reconciliation and harmony, as gods and men symbolically processed into the afternoon light of contemporary Athens.

Even the most casual reader of the Oresteia will recognize that it is constructed around a series of heartbreaking moral dilemmas, most of them matters of life and death. How does a man choose between duty to God and country or love of family? What love is greater—that for a child or a spouse? For father or a mother? What do we owe to tradition and morality and what to ourselves? What, finally, is justice, especially in a case of murder?

In the broadest sense, Aeschylus’ plays trace a progress from a culture of bloody, multigenerational vendettas to a culture based on jury trials in a court of law. Because of impossibly contradictory yet divinely appointed sanctions—you must revenge the death of a family member, you must not murder a family member—there has finally emerged a solution that shifts the responsibility of punishment from the individual to the state. The Oresteia ends, in scholar George Thomson’s phrase, “with the ratification of a new social contract, which is just because it is democratic.” Athens is transformed: the polis will now rely on the so-called Areopagite court for the proper redress of murder.

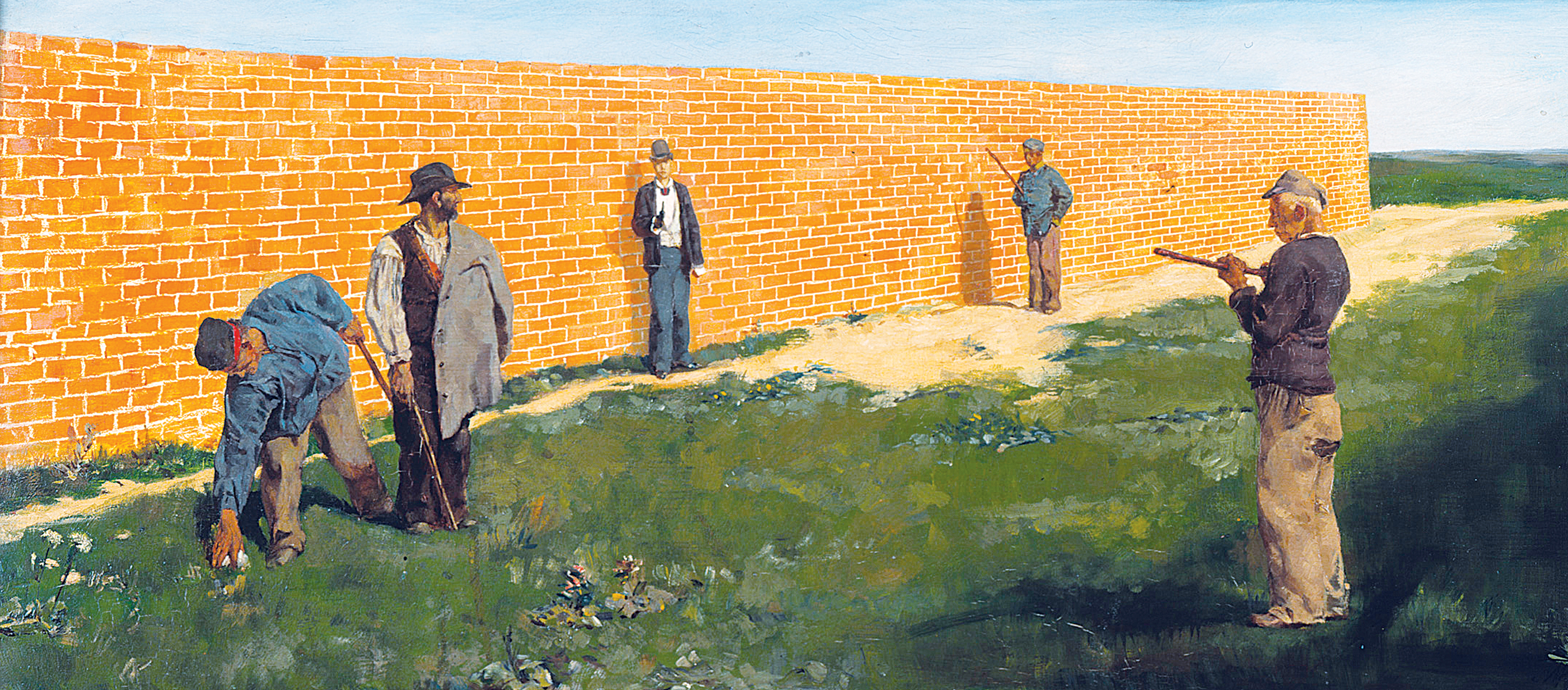

The Walker, by Max Klinger, 1878. Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany.

The chief impetus behind this new social contract has been the judicious and reasonable Athena. She represents the middle ground—a compromise between feuding parties as well as feuding sexes—being neither wife nor mother and having been conceived without sexual intercourse. (She emerged full-grown from Zeus’ forehead.) Nonetheless, her actual explanation for why she acquits Orestes still arouses controversy and argument. Does Athena really agree with Apollo that a man’s life is more important than a woman’s? Or is it merely a legal feint, needed for the success of her real goal: the transition from a primitive ethic of revenge to one based on justice and rule of law? Tellingly, Aeschylus the dramatist undercuts any obvious privileging of the male by making women the most forceful characters in the Oresteia, starting with Athena herself. Even Electra shows her mother’s mettle and spirit, while the formidable Clytemnestra and the enraptured Cassandra are arguably the most operatically magnificent figures in Greek drama. When she hears that her lover has been cut down, Clytemnestra immediately calls for a “man-slaying axe.”

Though the Oresteia ends in what one might call the light of reason, most of the actual imagery of the plays is darkly ominous: nets and snares, serpents, eagles, and hunted hares. When Orestes describes the punishment awaiting him if he fails to follow Apollo’s command to kill his mother, he speaks of “leprous ulcers that mount upon the flesh with cruel fangs / eating away its primal nature / and a white down sprouting forth upon this infection.” Cassandra’s mantic vision is even more terrifying:

Do you see here sitting near the house

these young ones, like to the shapes we see in dreams?

Children slain, as it were, by the hands of their kindred,

their hands full of the meat of their own flesh;

the vitals with the entrails I see them holding,

a pitiful load, of which their father ate.

The actual murders of Agamemnon, Cassandra, Aegisthus, and Clytemnestra take place offstage, but Aeschylus doesn’t shy away from close-ups of the corpses. Clytemnestra refers with satisfaction to the blood spattered on her clothes, of being struck by a sudden “dark shower of gory dew.” She likens killing Agamemnon to a kind of perverse sexual intercourse, as she describes how her blade again and again drove deep into his body. The first two plays, depicting a culture of violent bloodshed and endless payback, appropriately belong to the theater of cruelty and shock; Aeschylus, it was maintained in antiquity, was fond of “astonishment.” One can readily imagine a modern production in which a Francis Bacon or Willem de Kooning painted the masks of the Erinyes, whose eyes drip blood and whose mouths constantly vomit up clots of the blood they have sucked.

After the Sturm und Drang of Agamemnon and The Libation Bearers, The Eumenides ends with a spiritual joyfulness and serenity that recalls the close of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s The Magic Flute or Richard Wagner’s Parsifal. The quality of mercy and the forgiveness of sins override strict adherence to the letter of the law. It is interesting to note that in historical times one finds a similar development in the Icelandic sagas. Before the year 1000 these chronicles relate a kind of generational vendetta that is similar to what we see in Greek drama. But everything changes in 1000—the year that all Iceland converted to Christianity and made permissible the forgiveness of one’s enemies.

Justice?” writes William Gaddis in the first sentences of A Frolic of His Own. “You get justice in the next world, in this world you have the law.” The heart of the law, for the Greeks as for us, is inextricably intertwined with persuasion (Peitho), what Athena calls “the power to charm and soothe.” Clytemnestra flatters an ostensibly reluctant Agamemnon to tread on the luxurious tapestries—an act of hubris that hurries him to his doom. Apollo convinces Orestes, partly through threats, that he should avenge his father’s murder by killing his mother. Pylades reinforces his friend’s wavering resolve with a timely reminder. In the end, Athena persuades both Apollo and the Erinyes to abide by the decision of the jury—and then neatly coaxes the latter into accepting an honored place in the Athenian pantheon. Aeschylus repeatedly shows how words intertwine with all our actions, sometimes leading to savage revenge and sometimes to civilized resolution.

Wagner called the trilogy “the most perfect thing in every way, religious, philosophic, poetic, artistic.” He modeled his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk—the grand amalgam of music, dance, poetry, and ritual—after Aeschylus’ example. Eugene O’Neill actually retold the Oresteia in Mourning Becomes Electra, setting the action in a post–Civil War New England and emphasizing its Freudian elements. Jean-Paul Sartre’s The Flies, which appeared during World War II, remagined Orestes’ story as a parable about existential freedom. (To most critics, Aegisthus stands for the German occupiers of France, and Clytemnestra for the collaborationists.) T.S. Eliot borrowed aspects of the Oresteia for The Family Reunion, and Terence Rattigan in his wonderful play The Browning Version—about a long suffering classical scholar and his adulterous wife—uses Robert Browning’s translation of Agamemnon to signal cultural and personal loss. Even more recently, such esteemed poets as Robert Lowell, Ted Hughes, and Tony Harrison have loosely retranslated the trilogy into modern verse.

Murder, guilt, punishment, expiation—such are the grave and terrifying elements of the Oresteia. To err, alas, is simply human—and even an Aeschylus can hardly exhaust all the heart-wrenching complexities of crime and punishment. One must also reckon with Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Hamlet, all of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s major fiction, and such modern novels as Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock. Yet however shattering and artful such later works may be, in some ways they simply provide footnotes, additional illustrations, or further probings of the psychological and moral themes first presented in this greatest of all the Greek tragedies.