Reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

—George Washington, 1796The Courtesy of God

Never mind does God exist—does the God debate exist? Reexamining the relationship between faith and reason.

By Garret Keizer

Faith and Reason United, by Ludwig Seitz, c. 1887. Gallery of the Candelabra, The Vatican Museums, Vatican City.

The devil you say

These days what the Epistle of James says about believing in God—that the devils believe in him too, ergo beware of taking too much credit for your credos—is often on my mind. God may or may not be in his heaven, but on any given week he is likely to be enthroned at the top of that great chain of being known as the New York Times Best Sellers List. Like James and the devil, I am not impressed.

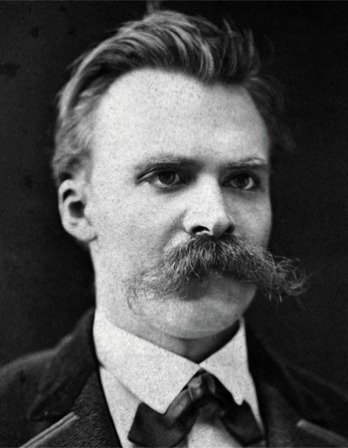

By that I do not mean that I consider myself beyond the God debate or beyond those of my fellow mortals who find it compelling. In fact, if there is any unifying notion in what you are about to read, it is my deep distrust of any human being who fancies himself “beyond” just about anything, be it money, jealousy (of best-selling authors, for instance), using a turn signal, or putting on a tie. I would never buy a book whose title began with Beyond, though I have known a few beyond-good-and-evil types who weren’t beyond stealing one.

If I am unimpressed with the God debate it is less for wanting to seem aloof than for needing to start with easier questions. Lacking the credentials, say, that entitle any expert on a nanolayer of slime covering a pebble called earth to give us the complete skinny on absolute being, a hubris beside which the nitwit ruling of a Kansas school board seems cautiously understated, I want questions better suited to my pay grade. Never mind does God exist—does the God debate exist?

I am not sure it does, or if it does, what it signifies besides a consumer culture’s endless obsession with buying the right accessories, the insignia most favored by one’s defined target group, the Jesus-fish trunk magnet or the Darwin fish with legs, or maybe a badge betokening higher evolution in the form of a chromium squirrel. The self-appointed champions of faith and reason doth protest too much, methinks.

The Vision Legend of the Fourteenth Century, by Luc Olivier Merson, c. 1872. Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, France.

The God Delusion author Richard Dawkins, for instance, argues that the practice of prayer is like talking to an imaginary friend, a textbook example of “begging the question”—in this case the question Dawkins’ book is dedicated to answering—a rhetorical fallacy most of the sixteen and seventeen year olds I used to teach grasped without much trouble, though getting them to spell non sequitur was a tougher slog. If this is the best “reason” can say for itself, God help us.

On the other hand, what leap of faith matches the breathtaking courage, to say nothing of the oxymoronic splendor, of the so-called atheistic humanist? To believe not only that millions of human beings have been deluded for thousands of years (and about a point of some consequence) but also that such specimens of humanity as Bach, Montaigne, Gandhi, John Coltrane, and Martin Luther King Jr. have been supremely deluded, and then to offer as a saving alternative to this delusional nonsense—drumroll, please, if only to drown out the irreverent guffaws—humanism! What is a virgin birth to that? Credibile est, quia ineptum est, “It is believable because it is ridiculous,” said fiery old Tertullian. No atheist and no humanist either, he had what it takes to be both.

Perhaps “the God debate” is an oxymoron, too. Simone Weil, working in the tradition of the theologia negativa, which holds that God is better defined by an is not than an is, suggested that atheists and theists were merely affirming different aspects of the same ineffable truth. Believers will balk at this; atheists are rarely pleased. Camus liked Weil, true, but then I’ve never been convinced Camus was an atheist. Camus was more of a wistful agnostic, a type I tend to trust: not beyond “losing their faith” but not beyond feeling sad about it either, the sort of people who don’t need to be water boarded to tell you which movie they really want to see.

Camus and Weil rate high in my hagiography, but the soul I’d rather meet if there’s such a place as heaven and if the auditing is sloppy enough to let me in is the father of Simone Weil’s friend Simone Deitz. At table Mr. Deitz would gently provoke the Catholic-leaning and habitually undernourished Weil to religious disputations so that in the passion of her arguments she would not notice him slipping extra pieces of steak onto her plate. Like another, considerably more famous Jew, he couldn’t seem to get beyond the idea that a young girl should eat. (“Little maid, arise,” says the wonder-working rabbi of Nazareth to Jairus’ comatose daughter, followed by a gag order and the recommendation of a light snack.)

That’s what’s missing most for me in the God debate: Mr. Deitz, his style of religious argument, his motive for it too. His pity and discretion. Convinced enough to write whole books, are God’s mightiest defenders convinced enough of his existence to give their lives toward establishing such a world as would make it easier to believe in divine benevolence? If celebrity atheists are really serious about debunking an idea that has given countless people some kind of handhold in the midst of horror and dread, might they devote at least a share of their royalties to treat the despair of those bereaved by the irresistible lucidity of their arguments? If religion is the opiate of the people, and if you love the people, then you must have a strong drug to offer when you tell them “Just say no.” Roosevelt believed in a New Deal but he also repealed Prohibition. His faith was not beyond pity.

Autumn in New York

The secularism championed by the infidels and vilified by the elect—that, too, is a discussion I can’t quite follow. Secular is not the opposite of sacred. Discussing God over cocktails while children die in drone attacks—that is the opposite of sacred, to say nothing of its relation to such fond ideas as human evolution.

I see the secular life of humanity as the self-effacing courtesy of God. “The marvelous courtesy and homeliness of our Father,” wrote Julian of Norwich, a fourteenth-century Englishwoman mystic who found me at a time when I needed her most. The God of Genesis puts man and woman (naked and utterly unencumbered by moral conundrums) in a garden, not a temple. In the heavenly city of Revelation there is no temple either, an absence the author makes a point of noting. Interesting, no, that front and back the Christian Bible makes the implicit declaration that the best of all possible worlds is what most of us would call secular.

Having presided as an Episcopal priest at so many funerals—none of them strictly “secular”—I find it easy to imagine my own. In addition to “We Gather Together to Ask the Lord’s Blessing,” as sung for generations by my dissenting ancestors, I would like the hymn “Autumn in New York,” as sung by Billie Holiday. In this I am not beyond tradition. My religion has always pictured heaven in the image of that most secular of all enterprises: a city.

Like many of the Hebrew prophets before him (Isaiah being a notable exception), Jesus was a country boy, so it’s no surprise that he got riled whenever he came near the pillars of power. But the religion that calls him Christ caught on as an urban phenomenon. Ephesians, Corinthians, Romans, Thessalonians, all those Pauline epistles bear witness to the spread of the new religion in urban centers. It was in the country where the pagans held out the longest, hardly atheists to be sure—if the religious illiteracy of our times is revealed in anything, it’s in the use of “pagan” as a synonym for “irreligious”—but deeply suspicious of the city and its secular enthusiasms.

I lack the natural religiosity of the true pagan. Except by the sea (but never far from a port), it is in urban centers where I feel God most powerfully, in the bustling secular that I glimpse heaven. The New England countryside where I live is full of the majesty of creation, yes, but its spiritual life often feels too Druidical for my tastes: chthonic powers and wind whistling in the hollow trees, Wiccan high priestesses stuffing their turkeys with wacky tobacky.

If so-called secularism has any drawback it is that it is not secular enough. The trouble lies with that little ism—not unlike the sad caboose of ianity coupled to the name of Christ. Given what we are, both suffixes are probably necessary. We need our little dogmas, and pity lets us have them. I know a novelist who tried for a while to write pseudonymously. The stories were all that mattered, he said. “People need an author,” his publisher finally told him. If what we call the secular is the courtesy of God, religion is God’s concession to those of us who need an author.

If the easy categorization rings false, it probably should. Lately I’ve been reading the published diary of a nineteenth-century clergyman named Francis Kilvert. In describing his pastoral rounds through the Welsh countryside—even when he makes no mention of God at all—his every utterance seems suffused with a sense of the divine, as if God were seeing the world through him. Shall we call Kilvert secular? Shall we say he reads like Meister Eckhart writing under a pseudonym?

An epicurean physician who occasionally dined with Dr. Johnson once said that he wished he was a Jew so that he could savor pork with the additional relish of sinning. There are some days when I wish I was an atheist so that I could feel Divinity’s love of the secular with the additional relish of having no name for what I felt, only knowing that, as Billie says of autumn in New York, “It’s good to live it again.”

The devil redux

If anything makes me nervous about people who abandon or abstract their belief in God, it’s what they begin to believe instead. They will tell you it is humanity or science; if only that were true. Historically what they have tended to believe in is evil.

By that I do not mean that they embrace evil, that man without God must perforce become a fiend. History shows us fiends of all creedal stripes, not a few of the worst with their hands fervently clasped in prayer. I mean rather that man without God has a marked historical tendency to feel the fiend breathing down his neck. The telltale heart of a “Godless society” is not a commercialized Christmas or a decommissioned Sabbath but an overblown Halloween.

Among those historical observations that we might call “sublimely interesting,” one of my favorites is the fact that the great age of witch hunting was the late Renaissance. It is Shakespeare’s monarch and patron King James I who writes Daemonologie (1597), a treatise on witchcraft that the Church Fathers of a thousand years before would have found laughable. (Along the same lines, St. Augustine would never have said that Jesus Christ was his “favorite philosopher,” if only for fear of demeaning Jesus.) In his classic intellectual history The Seventeenth Century Background, Basil Willey contends that as God became more remote to the early modern European imagination, the devil loomed larger. Still a medieval man at heart, Dante gives us a Satan about as compelling as a hamster; Milton’s is a pre-Romantic hero who speaks in pentameter verse. When George W. Bush gave his famous “Axis of Evil” speech, many people heard his language as “medieval.” To me he looked and sounded more like a Renaissance man, right down to the detail of his vice president standing like a Medici pope at his side.

Agnus Dei, by Francisco de Zurbarán, c. 1635-40. Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain.

The more “primitive” the Christianity, the less prominent the devil. Judaism, which Christians of the past and present fancy themselves beyond, is so primitive it hardly pays any attention to him at all. Golems, okay, but a master of metaphysical evil? “With such a son-in-law, I should need a Satan?” For the fourth- and fifth-century Christian hermits known as the desert fathers, the devil was real enough, but seems to have been something on the order of crabgrass or computer spam—nasty to be sure but perfectly manageable if you kept after it. According to patristic scholars Norman Russell and Benedicta Ward, one reason the hermits took to the desert had to do with their belief that the devils had taken flight from the cities to escape the sound of the Bible being read aloud there. In other words, the hermits were essentially on a mopping-up operation. Victory was already behind them.

Even the fantastic eschatology of the biblical Book of Revelation is entirely anticlimactic on this score. The beast appears and is immediately bound and cast into the lake of fire. I’ve known small-town exterminators to have a harder time with mice. Compare this confidence—and in the case of the desert fathers, their humor—with the fetishistic treatment of evil in American cinema, with the great Satan of the mullahs and the post-9/11 invocations of the dark side. Read the Modernist but equally Manichaean manifestos that damned tonal music as the spawn of the fascist beast, or the inquisitorial proclamations that if you like to read sonnets by dead white men you might as well go the whole nine yards and buy yourself a slave.

Then tell me a cheerful story, will you, about all the things we have evolved beyond.

May the Force take a hike

That said, I am more at ease with atheists than with sophisticated theists. I mean those people who say that God is far too big to care about their little woes, usually meaning that they are far too smart to fall for any such baloney. They are beyond anthropomorphism. They can spell anthropomorphism. For them God is sort of like a force—“whatever it was Einstein meant when he spoke of God,” as if they have a prayer of ever knowing. It is a most peculiar smugness. If I say that the source of all being is best likened to the force that assigns my sorry butt a number every time I step onto a bathroom scale, I deserve to live in the twenty-first century; if I say that this source is better likened to

Albert Einstein disheveled lover of elegant equations and gamey women, I am not fit to forgo saying grace in respectable company.

A deity who is “too big” to care for the minutiae of my secular life is as preposterous to me as a deity who rigs the raffle at St. Elizabeth’s so the parish can keep the car—and his proponents twice as vain in that they lack the forgivable inducement of the car. I would like to know what difference there is between John D. Rockefeller, who said God had made him rich, and his dot-com descendent, who says that a less anthropomorphic paradigm would make him believe. Actually, I do know the difference. The first looks out over Lake Michigan and wonders if God might be pleased to have a University of Chicago; the second parks his Beemer in the same place and takes a sanctified trot along the shore.

Religion is by no means a proper subject of conversation in mixed company.

—Philip Dormer Stanhope, 1754The sophisticated would not have prayed for my former altar girl Laney, though it was hard, seeing her rearranged in the ICU, to know exactly what to pray. For mercy, I guess. The jeep had dragged her for a ways, and she was not wearing a seat belt when it did. She was one of the most angelic presences I’ve ever known, handing me the communion bread, playing with the younger children after church, shining a light and a flashlight too for her uncles when they worked on their trucks, dancing with gravity on the balance beam. Later on she had a serious boyfriend, a job as a physical therapist, a life to call her own. She was studying the Japanese art of reiki, she told me on one of her less frequent visits to church, which was “like what Jesus did when he healed people with his touch.” Hers was the first funeral I was asked to do after I had stopped doing funerals. I bit my lip as I stood at the pulpit I had left only months before, angry at God and man, probably as sorry for myself as for the devastated family, the mother wearing that beatific expression I have learned over the years to recognize as the pity of some prescribing family physician, which these days must needs be combined with the courage to beard the FDA. At least as long ago as the seventeenth century, physicians were known for their atheism; Sir Thomas Browne offered his Religio Medici as a corrective. Here is my corrective: let those of us who believe what the devils believe never disdain the science that gave us drugs, or the physician whose only religion is the easing of pain.

As for Laney, she was no sure proof of God, and her disappearance proves nothing about God, but God feels a little less present to me because she is no longer in the world. My soul feels a little more tired. Little maid, pray for me.

Notice the quick slide to self-reference: the mark of religion at its lowest common denominator, blessme, blessme, blessme, like that scoundrel Jacob in the Bible, or whyme, whyme, whyme, like that complainer Job. Why Laney? Perhaps Orwell was thinking of Jacob when he said that the best explanation for anti-Semitism was to be found in the Old Testament. More than Camus and Weil put together, I love Orwell, but on that score he can take a hike, and may the Force be with him as he goes out the door.

I believe in the God of Jacob more than in the God of Stephen Hawking, though I believe not a little in the holiness of Stephen Hawking. I believe in the God of John Brown. To those who would tell me that I am but a short step away from saying I believe in the God of Osama bin Laden, I strenuously object. One half of a short step.

That is really the crux of the matter, isn’t it: what we talk about when we talk about God, at least in the context of what Americans with characteristic solipsism refer to as “our post-9/11 world”—with atheists telling us, “This is where religion inevitably leads,” and radio evangelists telling us, “This is where religion based on the Qur’an instead of the inspired Word of God inevitably leads,” and liberal apologists for monotheism telling us, “Come, come, ladies and gentlemen, we are surely beyond all that.” What 9/11 told us, what the death of Laney told me, is that we are beyond nothing, neither the childish question nor the primal cry, and least of all that desperate conjunction of the two, whether uttered by a Muslim zealot prostrate beneath the shadow of American might or a New York accountant racing down the doomed tower stairs: What must I do to be saved?

Credo

Which leaves the matter of why I’ve opted for the answers that I have, none of which places my faith beyond criticism or reproach. It turns out I believe in God for some of the same reasons that I believe in evolution, because I accept the testimony of estimable witnesses. “If everybody jumped off a cliff would you do that too?” If the right people did, I might.

But science is not like that, you will tell me; it allows you to look at the evidence and draw your own conclusions. Yes it does, and thanks for the reminder, but I am lying through my teeth if I say that it makes perfect sense to me that you have this amoeba and then, after billions of years and any number of extraordinarily fortuitous mutations, you have Marilyn Monroe singing “Happy Birthday, Mr. President.” As if that weren’t enough, you have a creature capable of recalling the scene with more emotions than there were candles on the cake: nostalgia and cynicism, poignancy and lust, an atavistic prick of what the Neanderthals felt when they buried their dead with a sprinkling of red ochre. Many happy returns, Jack. Sing on, Norma Jean. Tell me one more time, Mr. Darwin.

I suppose I should add that I also find it hard to believe that a chimp at a typewriter will eventually produce War and Peace. I think a chimp at a typewriter will eventually produce a gun and blow out his brains. Futility can be endured for only so long. Tolstoy understood that, which is perhaps another reason, besides the bulk of his tome, that we use War and Peace in the example. A chimp at a typewriter is what I often feel like, with the additional and bitter relish that, unlike the chimp, I want to produce War and Peace, or something like it, and I suspect that no matter how many trillions of years I had, I never could. So, like any animal in existential distress, I emit a cry—and for reasons the animal itself may not fully understand.

I’m getting warmer, which is to say closer to the flush of embarrassment that comes over us when we cut through the cant and actually say which movie we really want to see, which one gets us crying every time.

When everything else falls away, my Calvinist upbringing, my prissy love of English church architecture, my sense of connection to Johns Donne and Brown, my contrarian orthodoxy, the please-never-die faces of those who have helped me believe in supernatural love, this is all that remains: I called and He heard. “Out of the depths have I called to thee, O Lord”—as have others who called without any requiting consolation, not even that of knowing for certain that calling in this way was a joke. “Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?” [My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?] He belongs to them more than me.

The Angelus, by Jean-François Millet, c. 1857–59. Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France.

In positioning my faith like this, and not in a proposition more arguable, I leave myself with little defense against the charges of infantilism, autosuggestion, lunacy itself. Yet among those who would gleefully sign the papers for my committal are individuals who will tell you that it’s possible for a capitalist society to produce a healthcare system in which making many people well can and will take precedence over making a few people rich. They have their magical thinking, I have mine.

For the record mine is not a restatement of that old platitude about there being “no atheists in the foxholes.” Given the godforsaken cast of most battlefields, I should not be surprised to learn that there are nothing but atheists in the foxholes. It is only that some of the atheists manage to pray.

That is what I did when I began this essay. I knew that one of my reasons for taking it on was that I needed the money, and that most of the others, including some I might have regarded as nobler, were probably just as base. I did not feel that God, being God and the God of Jacob to boot, needed to be told my motives, or that I necessarily needed to be forgiven for them. Interviewing applicants for a temporary job blowing the shofar, some rabbis are said to have asked each of three finalists what he was thinking during his audition. “I thought of the Blessed One calling creation into being,” said the first. “I thought of the Law given on Mount Sinai,” said the second. Sheepishly the third confessed, “I thought that I have six daughters, and they all need dowries.” The rabbis didn’t need to go beyond that. They hired the third, they slipped the man a little steak, though I’m not sure if that was because they pitied his predicament or admired his nerve.

No, if I prayed, it was mainly because I was deeply skeptical, not of God but of the value of talking about God. “We need more cooks, not more cookbooks,” reads the epigraph on a well-known cookbook, and after so many years of imparting recipes from behind a pulpit I find myself wishing I’d spent more time in front of a stove. Still there was the matter of a dowry, and thus the need of a job. So I prayed I could pull it off, I prayed for mercy, I prayed that I would write something capable of gently unsettling every single human being who troubled to read it. In a word I prayed for the chimp. Of course I am in no position to tell anyone whether God exists. But perhaps you are in a position to tell me whether God answers prayers.