Long Island

At the entry of this bay is a little craggy island about one or two miles long called Coney Island. Before I came to New York Ferry, I rode a byway where, in seven miles’ riding, I had twenty-four gates to open. Dromo, my servant, being about twenty paces before me, stopped at a house where, when I came up, I found him discoursing a Negro girl who spoke Dutch to him. “Dis de way to York?” says Dromo. “Yaw, dat is Yarikee,” said the wench, pointing to the steeples. “What devil you say?” replies Dromo. “Yaw, mynheer,” said the wench. “Damme you, what you say?” said Dromo again. “Yaw, yaw,” said the girl. “You a damn black bitch,” said Dromo and so rid on. The road here for several miles is planted thick upon each side with rows of cherry trees, like hedges, and the lots of land are mostly enclosed with stone fences.

York Ferry

At five in the afternoon I called at one Baker’s that keeps the York Ferry where, while I sat waiting for a passage, there came in a man and his wife that were to go over. The woman was a beauty, having a fine complexion and good features, black eyes and hair, and an elegant shape. She had an amorous look, and her eyes, methought, spoke a language which is universally understood. While she sat there, her tongue never lay still, and though her discourse was of no great importance, yet methought her voice had music in it, and I was fool enough to be highly pleased to see her smiles at every little impertinence she uttered. She talked of a neighbor of hers that was very ill and said she was sure she would die, for last night she had dreamed of nothing but white horses and washing of linen. I heard this stuff with as much pleasure as if Demosthenes or Cicero had been exerting their best talents, but meantime was not so stupid but I knew that it was the fine face and eyes and not the discourse that charmed me. At six o’clock in the evening, I landed at New York.

New York

This city makes a very fine appearance for above a mile all along the river, and here lies a great deal of shipping. I put my horses up at one Waghorn’s at the Sign of the Cart and Horse. There I fell in with a company of toapers. Among the rest was an old Scotsman, by name Jameson, sheriff of the city, and two aldermen whose names I know not. The Scotsman seemed to be dictator to the company; his talent lay in history, having a particular knack at telling a story. In his narratives he interspersed a particular kind of low wit well-known to vulgar understandings. And having a homely carbuncle kind of a countenance with a hideous knob of a nose, he screwed it into a hundred different forms while he spoke and gave such a strong emphasis to his words that he merely spit in one’s face at three or four foot’s distance, his mouth being plentifully bedewed with salival juice, by the force of the liquor which he drank and the fumes of the tobacco which he smoked. The company seemed to admire him much, but he set me a-staring.

After I had sat some time with this polite company, Dr. Colchoun, surgeon to the fort, called in, to whom I delivered letters, and he carried me to the tavern which is kept by one Todd, an old Scotsman, to sup with the Hungarian Club, of which he is a member and which meets there every night. The company were all strangers to me except Mr. Home, secretary of New Jersey, of whom I had some knowledge, he having been at my house at Annapolis. They saluted me very civilly, and I, as civilly as I could, returned their compliments in neat short speeches such as, “Your very humble servant,” “I’m glad to see you,” and the like commonplace phrases used upon such occasions. We went to supper, and our landlord Todd entertained us as he stood waiting with quaint saws and jack-pudding speeches. “Praised be God,” said he, “as to cuikry, I defaa ony French cuik to ding me, bot a haggis is a dish I wadna tak the trouble to mak. Look ye, gentlemen, there was anes a Frenchman axed his frind to denner. His frind axed him ‘What ha’ ye gotten till eat?’ ‘Four an’ twanty legs of mutton,’ quo’ he, ‘a’ sae differently cuiked that ye winna ken whilk is whilk.’ Sae whan he gaed there; what deel was it, think ye, but four and twanty sheep’s trotters, be God.’” He was a-going on with this tale of a tub when, very seasonably for the company, the bell, hastily pulled, called him to another room, and a little after we heard him roaring at the stair head, “Dam ye bitch, wharefor winna ye bring a canle?”

After supper they set in for drinking, to which I was averse and therefore sat upon nettles. They filled up bumpers at each round, but I would drink only three which were to the king, Governor Clinton, and Governor Bladen, which last was my own. Two or three toapers in the company seemed to be of opinion that a man could not have a more sociable quality or endowment than to be able to pour down seas of liquor and remain unconquered while others sunk under the table. I heard this philosophical maxim but silently dissented to it. I left the company at ten at night pretty well flushed with my three bumpers and, ruminating on my folly, went to my lodging at Mrs. Hogg’s in Broadstreet.

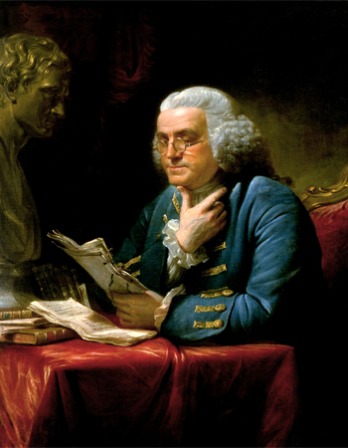

From The Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton received a medical degree from the University of Edinburgh in 1737, writing his thesis on bone disease; two years later, he moved to Annapolis, where he set up a successful practice. Suffering from tuberculosis—“I shall only say that I am not well in health and for that reason chiefly continue still a bachelor”—Hamilton decided to tour the colonies with his slave Dromo; they traveled more than sixteen hundred miles in a little over four months.

Back to Issue