At eight thirty on the dot a cab pulled up in front of Filo’s house. Filo had ordered it, for she was as excited as I was and she wanted everything to go right for the night of my debut with King Oliver at Lincoln Gardens. It is a funny thing about the music, fame, and show business: no matter how long you have been in the profession, opening night always makes you feel as though little butterflies were running around in your stomach.

Mrs. Major, the white lady who owned the Gardens, and Red Bud, the colored manager, were the first people I ran into when I walked through the long lobby. Then I ran into King Jones, a short fellow with a loud voice you could hear over a block away when he acted as master of ceremonies. (He acted as though he was not a colored fellow, but his real bad English gave him away.)

When I reached the bandstand there was King Oliver and all his boys having a smoke before the first set and waiting for me to show up. The place was filling up with all the finest musicians from downtown, including Louis Panico, the ace white trumpeter, and Isham Jones, who was the talk of the town in the same band.

I was thrilled when I took my place with that grand group of musicians: Johnny and Baby Dodds, Honore Dutrey, Bill Johnson, Lil Hardin, and the master himself. It was good to be playing with Baby Dodds again; I was glad to learn he had stopped drinking excessively and had settled down to his music. He was still a wizard on the drums, and he certainly made me blow my horn that night when I heard him beat those sticks behind one of my hot choruses.

Bill Johnson, the bass player, was the cat that interested me that first evening at the Gardens. He was one of the original Creole Jazz Band boys and one of the first to come North and make a musical hit. He had the features and even the voice of a white boy—an ofay, or Southern, white boy at that. His sense of humor was unlimited.

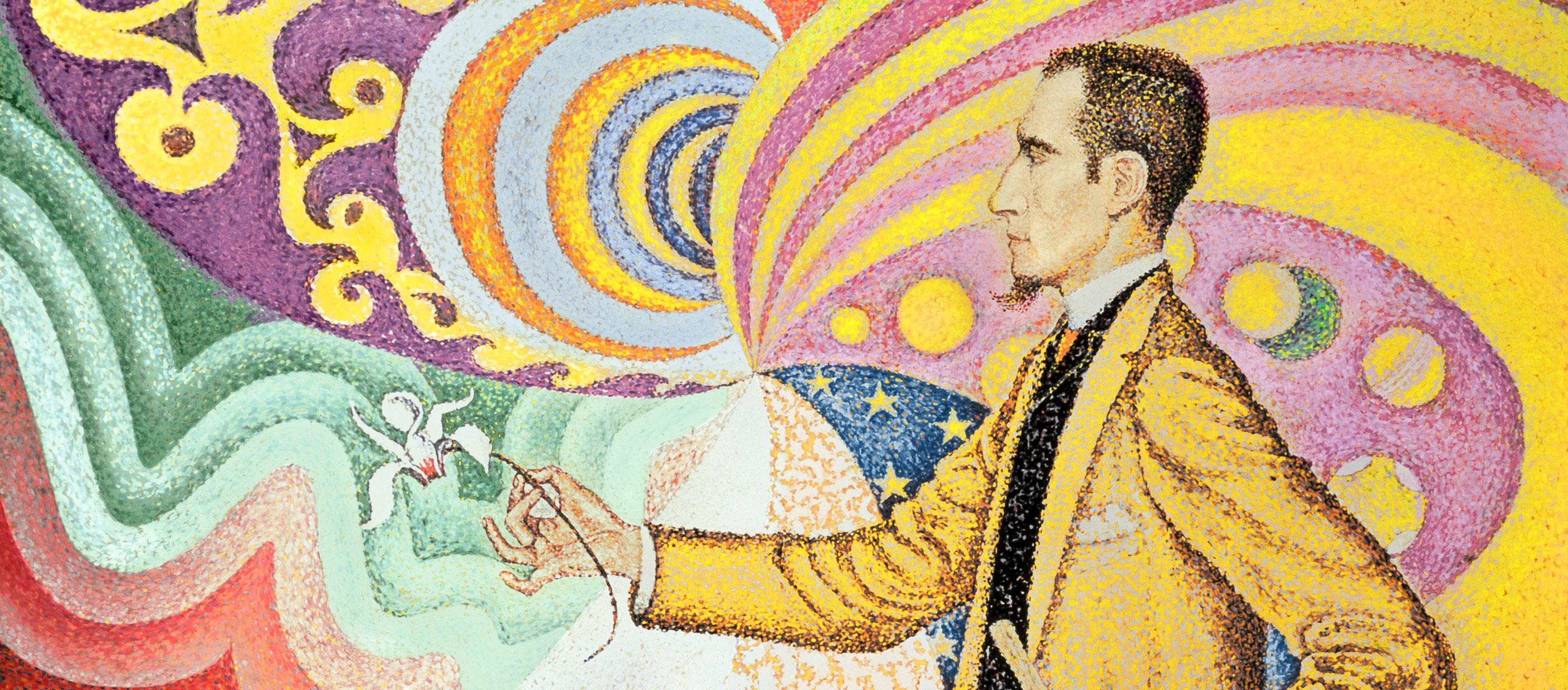

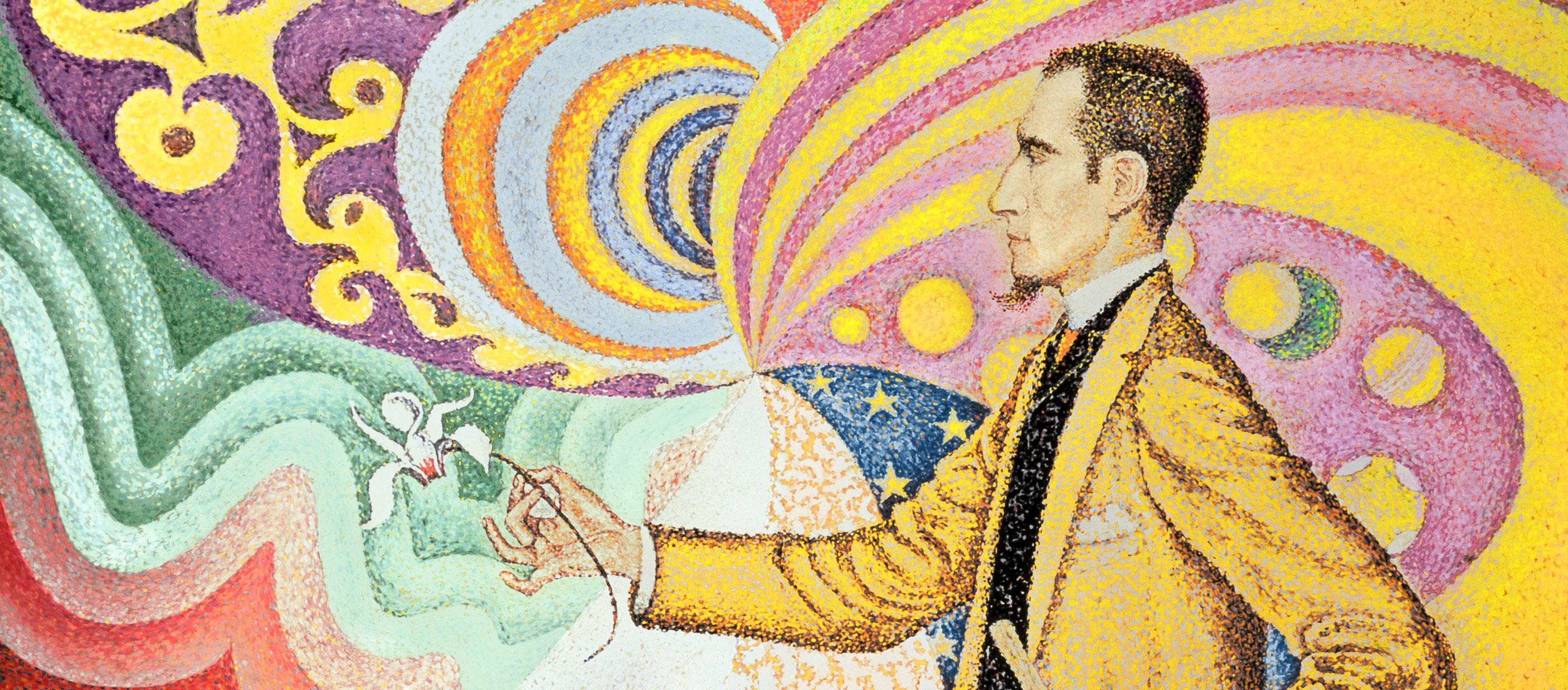

Opus 217. Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones and Tints, Portrait of Félix Fénéon in 1890, by Paul Signac, 1890. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York.

For a woman Lil Hardin was really wonderful, and she certainly surprised me that night with her four beats to a bar. It was startling to find a woman who had been valedictorian in her class at Fisk University fall in line and play such good jazz. She had gotten her training from Joe Oliver, Freddy Keppard, Sugar Johnny, Lawrence Dewey, Tany Johnson, and many other of the great pioneers from New Orleans. If she had not run into those top notchers she would have probably married some big politician or maybe played the classics for a living. Later I found that Lil was doubling after hours at the Idleweise Gardens. I wondered how she was ever able to get any sleep. I knew those New Orleans cats could take it all right, but it was a tough pull for a woman.

When we cracked down on the first note that night at the Lincoln Gardens, I knew that things would go well for me. When Papa Joe began to blow that horn of his it felt right like old times. The first number went over so well that we had to take an encore. It was then that Joe and I developed a little system for the duet breaks. We did not have to write them down. I was so wrapped up in him and lived so closely to his music that I could follow his lead in a split second. No one could understand how we did it, but it was easy for us, and we kept it up the whole evening.

I did not take a solo until the evening was almost over. I did not try to go ahead of Papa Joe because I felt that any glory that came to me must go to him. He could blow enough horn for both of us. I was playing second to his lead, and I never dreamed of trying to steal the show or any of that silly rot.

Every number on opening night was a gassuh. A special hit was a piece called “Eccentric,” in which Joe took a lot of breaks. First he would take a four-bar break, then the band would play. Then he would take another four-bar break. Finally at the very last chorus Joe and Bill Johnson would do a sort of musical act. Joe would make his horn sound like a baby crying, and Bill Johnson would make his horn sound as though it was a nurse calming the baby in a high voice. While Joe’s horn was crying, Bill Johnson’s horn would interrupt on that high note as though to say, “Don’t cry, little baby.” Finally this musical horseplay broke up in a wild squabble between nurse and child, and the number would bring down the house with laughter and applause.

After the floor show was over, we went into some dance tunes, and the crowd yelled, “Let the youngster blow!” That meant me. Joe was wonderful and he gladly let me play my rendition of the blues. That was heaven.

Papa Joe was so elated that he played half an hour over time. The boys from downtown stayed until the last note was played, and they came backstage and talked to us while we packed our instruments. They congratulated Joe on his music and for sending to New Orleans to get me. I was so happy I did not know what to do.

I had hit the big time. I was up north with the greats. I was playing with my idol, the King, Joe Oliver. My boyhood dream had come true at last.

© 1954 by Louis Armstrong. Used with permission of Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation, Inc.

From Satchmo. Growing up in turn-of-the-century New Orleans, Armstrong learned to play cornet while at a home for juvenile delinquents. In the 1930s he toured America and Europe, becoming a dominant influence on the swing era and one of the originators of scat singing. The bandleader, comedian, and film star died at the age of seventy-one in 1971.

Back to Issue