I always thought of photography as a naughty thing to do—that was one of my favorite things about it—and when I first did it, I felt perverse.

—Diane Arbus, 1950In the Gloom the Gold

Consider the legacy of Ezra Pound—no poet has ever been so influential, so controversial, and so little read.

By Jamie James

Rain, Steam and Speed—The Great Western Railway, by J.M.W. Turner, 1844. National Gallery.

Ezra Pound never made it easy. He was a poet who cared little about public success and not at all about money: he dedicated his life to art with the rapturous abandon of a bacchant. Pound saw himself as forging ahead on the path poets had pursued since the preclassical bards, toward deeper wisdom and a more perfect expression, in pursuit of the beautiful. In the years since his death, this perennial vision of an enlightened Republic of Letters, one of humankind’s greatest intellectual accomplishments, has quietly gone the way of falconry and intaglio carving. So impenetrable and taxing do Pound’s poems appear to most modern readers that the soaring ambition of his work has been eclipsed by the neatly plotted narrative of his life.

Everybody knows the story. Pound launched the Imagist movement, epitomized by that hardy perennial of poetry anthologies, “In a Station of the Metro” (in full: “The apparition of these faces in the crowd; / Petals on a wet, black bough”), and then played a decisive role in shaping T.S. Eliot’s epochal masterpiece The Waste Land. He devoted the rest of his life to composing The Cantos, a vast, unreadable epic left unfinished at his death in 1972. The story ends badly: he went off the rails during the war years, embracing fascism and anti-Semitism in broadcasts for Mussolini that got him arrested for treason, and was eventually committed to a mental hospital.

As conventional wisdom goes, the standard skinny on Pound is no worse than most. True to the genre it lacks nuance, emphasizing controversy over substance, but it isn’t actually wrong about anything—except the work. Pound’s Imagist poetry was revolutionary but by no means the best even of his early compositions, and The Cantos are called unreadable by the same people who call Tristram Shandy and Ulysses unreadable, those who haven’t read them. Many of the cantos are as deeply felt and exquisitely rendered as any verse in English. No poet has ever been so influential, so controversial, and so little read.

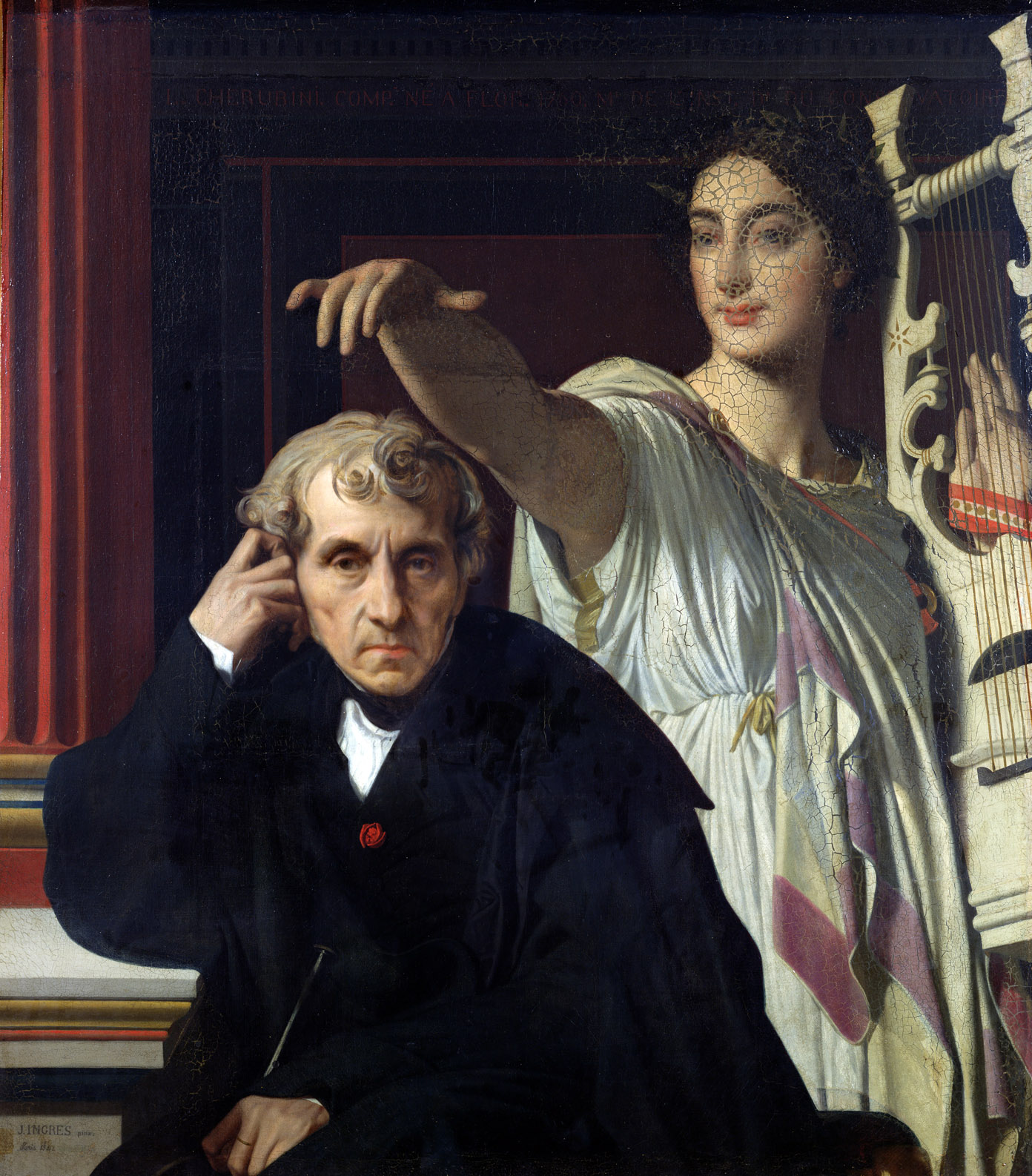

Composer Luigi Cherubini and a Muse, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1842. Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

Born in Hailey, Idaho, and raised in suburban Philadelphia, Pound arrived in London in 1908 at the age of twenty-two with £3 in his pocket. Ford Madox Ford recorded this impression of the young genius in London: “Ezra would approach with the step of a dancer, making passes with a cane at an imaginary opponent. He would wear trousers made of green billiard cloth, a pink coat, a blue shirt, a tie handpainted by a Japanese friend, an immense sombrero, a flaming beard cut to a point, and a single, large blue earring.”

Pound worked indefatigably to promote the work of other writers, sometimes to the neglect of his own career. Beside shepherding The Waste Land into print, he played an active role in launching and promoting the careers of nearly all the major modernist writers. He served Yeats, already an established poet, as an unpaid amanuensis and factotum, an intimacy he used to exert as profound an effect on the elder poet’s mature style as he did on young Eliot. Pound arranged for the first publication of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in The Egoist; as an editor for the Three Mountains Press in Paris, he himself published Hemingway’s second book, In Our Time; he raised the money for Ford Madox Ford to launch the Transatlantic Review. As the European correspondent for Poetry magazine, Harriet Monroe’s landmark magazine published in Chicago, Pound got into print the early work of his college sweetheart Hilda Doolittle (H.D.), Robert Frost, D.H. Lawrence, William Carlos Williams, and many other writers who have since faded from notice.

In those early London days, Ezra Pound was a one-man arts foundation with no endowment except his own energy and generosity. No matter how poor he was, he always scraped together a few pounds for sickly, insecure Eliot and imperiously demanding Joyce, who took away a suit, a pair of boots, and a wad of cash from his first meeting with the enthusiastic American. Pound wasn’t motivated by altruism so much as sheer obstinacy, what the British mean by bloody-mindedness: he was a stage mother who wanted his charges to go out there and shine.

The triumph of modernism was complete by 1922, the year of The Waste Land (dedicated to Pound, “the better craftsman”) and Ulysses (the majority of which was previously serialized in the Little Review, an American journal for which Pound served as European editor), but the movement’s high pontiff had just begun work on his own monument, which would far overtop those of his comrades in scope. If Ulysses made a microcosm of Dublin, The Cantos would be a cosmos entire. The scale of Pound’s concept was immeasurable. It would be the literary equivalent of the map in Jorge Luis Borges’ fable “The Exactitude of Science,” about a vanished civilization where “the Academies of Cartographers created a Map of the Empire that was the same size as the Empire and coincided with it point by point.” [my translation] In Pound’s “tale of the tribe,” as he called his epic, there was room for everything.

The first installment in book form was A Draft of XVI Cantos for the Beginning of a Poem of Some Length, published in Paris in January 1925. It opens with the Odyssey (written in Renaissance Latin) and goes on to encompass Confucius, Aeschylus, Ovid, Poem of My Cid, the Languedoc troubadours, Dante, Renaissance Italian history, Camõens, Browning, Flaubert,

Henry James, and Lenin, to name only the most important sources, in free verse larded with gobs of Latin, Greek, Spanish, Italian, French, and Provençal. The Cantos would be an epic for the twentieth century, a polyphonic treasure-house enshrining humankind’s noblest instinct, the aspiration after the beautiful and the good.

Twenty years later, imprisoned in a wire cage in Pisa by his own countrymen, charged with treason, Pound wrote in canto 80, “Beauty is difficult.” In 1969, New Directions, his loyal American publisher, brought out Drafts & Fragments of Cantos CX-CXVII, the final sputtering-out of the great project. Pound despairingly told a friend, “I botched it.”

U lysses and The Waste Land were instant classics, as famous and passionately discussed as any new works in the history of English literature, yet The Cantos have remained an outlier, stubbornly resisting assimilation into the mainstream or even a well-traveled tributary. It was difficult enough simply to find the text. Various cantos were only available in excerpts in small magazines and expensive limited editions until 1933, when Farrar & Rinehart in New York published a cheap edition of A Draft of XXX Cantos. Hemingway lauded the book’s appearance: “The best of Pound’s writing—and it is in the Cantos—will last as long as there is any literature.” In the twenty-first century, Hemingway’s words sound more like a curse on literature than a rosy prediction of Pound’s staying power. 1939, the year of Yeats’ death and the publication of Finnegans Wake, was also the year Hitler invaded Poland. As the world plunged into chaos, fewer readers had the time and motivation to puzzle through verse that was bestrewn with Chinese ideograms, Renaissance music notation, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and Sumerian pictographs.

Yet it isn’t just the poem’s textual difficulties that have relegated The Cantos to the suffocating gloom of graduate programs. Hugh Kenner, the critic almost singlehandedly responsible for resurrecting Pound’s reputation in the postwar era, offered a persuasive explanation for the work’s relative obscurity in The Pound Era, one of the last great works of literary criticism aimed at the general reader, published shortly before the poet’s death. “There is no substitute for critical tradition: a continuum of understanding, early commenced.” The Waste Land and Ulysses have been a part of the cultural wallpaper for so long that they are no longer threatening, but to most readers The Cantos seem like a text in a lost language, a maddening, indecipherable enigma. “Hence the paradox,” Kenner concluded, “that an intensely topical poem has become archaic without ever having been contemporary.”

The Funeral of Shelley, by Louis-Edouard Fournier, 1889. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, England.

The topicality was exactly the problem. The middle cantos dealt with the radical economic theories of Major C.H. Douglas, which held that credit and the control of capital by private banks was the root cause of economic depressions and the perpetual poverty of workers. Pound’s imagination was possessed by the conviction that credit (usura, in the vocabulary of The Cantos) was responsible for world war and the decline of civilization, ideas he bolstered with his wonted erudition by excursions into American history and the annals of imperial China.

In 1924 Pound relocated to Italy and became enamored of the Fascist movement, which he believed was putting his beliefs about money and labor into practice. He admired Mussolini with an intensity approaching hero worship. When Pound finally met Il Duce in 1933, he presented him with a copy of A Draft of XXX Cantos. Mussolini leafed through it and said, “How amusing,” a commonplace pleasantry that Pound cited again and again as revealing an instinctive understanding of the work. The poet imaginatively transformed the dictator into a new humanist hero in the pattern of Odysseus, restoring order and nobility to the world.

Pound was deluded but far from alone. The conventional wisdom neglects to recall that before Mussolini’s alliance with Hitler, but years after his thuggish tactics were well-known, he had fervent boosters in the Western democracies. Richard Washburn Child, the American ambassador in Rome from 1921 to 1924, wrote a preface to Mussolini’s autobiography that was almost idolatrous in tone. While on a visit to Italy in 1927, Winston Churchill remarked to journalists, “If I were an Italian I would don the fascist black shirt,” later declaring on his home soil that Mussolini was “the greatest living legislator.”

Pound went beyond admiration to active collaboration. In January 1941 he began a series of polemical broadcasts on Rome Radio, which extolled the genius of Mussolini and vilified Roosevelt and Churchill as the tools of munitions makers and bankers, with many stinging anti-Semitic barbs. Pound was utterly inept as an Italian version of Tokyo Rose; many of his broadcasts were so incoherent that fascist authorities wondered if he was an American spy. In America and Europe, attempts were made to banish his work to the margins of respectable literature. In 1942, Poetry, the magazine for which he had labored so mightily and done so much good, had opined in an editorial, “The time has come to put a formal end to the countenancing of Ezra Pound.”

As appalling as appearances were, in his own mind Pound was not disloyal to his country. John Adams is one of the principal heroes of The Cantos; in the intensely patriotic canto 65, published in 1940, Pound quotes Adams, “For my part thought that Americans/Had been embroiled in European wars long enough,” with a heavy black line printed in the margin for emphasis. Yet Pound’s political idealism, earnest though it may have been, was getting demented. He purported to defend the principles of the U.S. Constitution in his broadcasts for fascist radio. Enthusiasm had become mania. Hemingway found a useful measure of the man. “Ezra was right half the time, and when he was wrong, he was so wrong you were never in any doubt about it.”

The case for treason against Pound was never tried in a court of law, but the charge of anti-Semitism is open-and-shut. He began with the genteel, drawing-room prejudice of Bloomsbury and Oxford in the years before the Great War and amplified it with his obsessive loathing of the international banking system. Hemingway’s half-wrong/half-right formula applies here. Much of what Pound had to say about the destructive effects of credit was sound—and seems even more so after the collapse of the global credit market in 2008. The “usura” canto (45) is one of the most powerful English poems of the twentieth century.

His fatal lapse of judgment was accepting the medieval conflation of moneylenders with Jewry. Yet in this as in everything, Pound’s views were complex, if not contradictory. After he was arrested, he composed a cable to President Truman offering his recommendations for securing the postwar peace: leniency for Germany, American control of Italy until elections could be held, and the establishment of a state in Palestine as a “national home and symbol of Jewry.” Later, in 1967, when Allen Ginsburg came calling, Pound told him, “The worst mistake I made was that stupid, suburban prejudice of anti-Semitism.”

At the end of the war, Pound was arrested and transferred to a U.S. Army prison camp in Pisa. Held in total isolation in a six-foot-square cage open to the elements, he collapsed after three weeks and was moved to an officer’s tent to recover. There he composed cantos 74 to 84, published in 1948 as The Pisan Cantos. He wrote the first pages (and thus the cycle’s majestic opening line, “The enormous tragedy of the dream in the peasant’s bent shoulders”) on toilet paper. The only books he had were a text of Confucius and a Chinese dictionary he had had in his pocket when he was arrested, a camp-issued Bible, and a paperback poetry anthology he found in the privy.

After The Pisan Cantos were published, T.S. Eliot led a successful campaign to give Pound the first Bollingen Prize for poetry, a new award administered by the Library of Congress. The decision was engulfed in flames of patriotic controversy. The New York Times headline read: “Pound, in Mental Clinic, Wins Prize for Poetry Penned in Treason Cell,” expressing a common view. The American literary establishment rose in defense of the poet, who had been declared a mental incompetent and confined to St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, DC. Pound prepared a statement for the press: “No comment from the Bug House.”

The principal complaint against Pound has always been his difficulty, finally simplified to the conventional wisdom that The Cantos are obscure, unreadable gibberish. It is a false charge. Most of The Cantos speak more plainly to a modern reader than a typical love lyric by John Donne. No poet has ever demanded more learning from his readers, but Pound was never deliberately obscure. His greatest asset, his pitch-perfect ear, developed into a passion for exactitude of expression. He frequently quoted as his core belief Confucius’ formula in The Great Learning that good government depends upon order in the family, which depends upon order in yourself, and that in turn requires that you rectify your own heart. To do that you must seek “precise verbal definitions of [your] inarticulate thoughts (the tones given off by the heart).” To abuse language, to twist the meanings of words to suit ideological or commercial purposes, is an intellectual crime that threatens the harmony and very integrity of the social order, a rigorous view that parallels George Orwell’s, acerbic investigations of institutional language.

I cannot live without books, but fewer will suffice where amusement, and not use, is the only future object.

—Thomas Jefferson, 1815After the generation of Eliot and Pound, with the decline of classical education in American schools and colleges, literature was increasingly seen as an elective specialty rather than an essential activity of every civilized man. Latin may still enjoy a periodic popularity, but in the twentieth century the study of ancient Greek became a rarefied, esoteric pursuit. Greekless readers today may view words in the ancient language as a pretentious affront; yet for Pound, it enlarged his ability to capture precisely the tones given off by the heart. Virtue, for example, isn’t the same thing as ἀρετή. The Greek word, derived from Ares, the war god, brings in the idea of manly courage; the English word, borrowed from French and rooted in Latin vir (“man”), expresses a heart-tone polished and colored by 750 years of usage, from Wycliffe and Chaucer down through to Benjamin Jowett’s use of the word in 1875 to approximate ἀρετή in his standard translation of Plato’s Republic.

Pound had no use for readers who weren’t interested in such distinctions. Being unable to read Greek (or Latin or Provençal or any of the languages he mastered) was simply an obstacle to be overcome. He didn’t expect his readers to know the meaning of an Egyptian hieroglyph printed on the page, but he expected them to be interested by it and not to flee in confusion. To acquire a familiarity with all the literature that Pound alludes to in The Cantos would require a lifetime of reading and study: that was the idea.

Did he botch it? He aimed too high, no doubt, with his 1:1 scale map of the empire of the human heart. Confucius, Homer, and Dante form a solid foundation for a universal epic, but to allocate pages to Martin Van Buren and Pietro Leopoldo, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1765–90), and no space to Milton or Wordsworth is simply eccentric. Kenner may have done more harm to the cause than good by recommending that The Cantos be read straight through. Few readers will find much pleasure in the last “line” of canto 33:

…….& Company’s banker was in that meeting, and next day he was out after a loan of 60 millions, and got it. Swiftarmoursinclair but the country at large did not know it. The meeting decided we were over-inflated.

after having been ravished by passages such as this ecstatic transfiguration of the Venetian lagoon in canto 17:

And the waters richer than glass,

Bronze gold, the blaze over the silver,

Dye pots in the torchlight,

The flash of wave under prows,

And the silver beaks rising and crossing.

Stone trees, white and rose-white in the darkness,

Cypress there by the towers,

Drift under hulls in the night.“In the gloom the gold

Gathers the light about it.”

Pound’s artistic credo was “Make it new,” borrowed from the inscription in the bathtub of the legendary Chinese emperor Tang, who founded the Shang dynasty in the sixteenth century bc. Pound made poetry new by globalizing its language and expanding its subject matter to all that the human mind can encompass. The most astonishing accomplishment of The Cantos was the mad courage of its conception.

It was an aspiration that could never be surpassed, and therein lay its ruin. In Borges’ ficción, after the creation of the monstrous life-size map of the empire, “Succeeding Generations, less Addicted to the Study of Cartography, understood that this enlarged Map was useless and not without impiety they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of the Sun and Winters.” Something like that happened in poetry after Ezra Pound.

To update

Virginia Woolf, on or about November 1972, human character changed. As arbitrary as Woolf in her choice of December 1910, I have taken the month of Pound’s death. Auden died a year later, or you might push it forward to 1977, the year Robert Lowell died; but around that time poetry lost its numen. “I am not saying,” wrote Woolf, “that one went out, as one might into a garden, and there saw that a rose had flowered, or that a hen had laid an egg. The change was not sudden and definite like that. But a change there was, nevertheless.”

In 1919, in his first major essay, “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” T.S. Eliot laid down the law: art never improves. He didn’t bother to posit the corollary, neither does it decline, and it would have been inconceivable to Eliot that the art of poetry might one day simply wither away for lack of interest. Yet that is what has happened. That is the change: modern ears have been sealed to the music of poetry. Now most Americans seek the new with their eyes.

Concert in the Egg, attributed to Hieronymus Bosch, sixteenth century. Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, Lille, France.

The change really is a sensory civil war, a triumph of the eye over the ear. A diamond-encrusted skull exhibited in an art gallery glitters brightly enough to capture the public imagination for a moment, but the audience for serious new concert-hall music has dwindled. Stubborn music programmers insist that audiences take a dose of new music (usually under ten minutes, often before the intermission), yet even a landmark work such as Schoenberg’s Five Orchestral Pieces, Op. 16, still makes many concertgoers fidget ninety-eight years after its premiere.

Nonetheless, Eliot’s law holds. The quality of talent available to serve the Muses is constant: I don’t mean to say that poetry in our own era is less accomplished and artistically worthy than it was in the old days. There is always gold in the gloom. Among the contemporary poets I admire, I return with particular pleasure to Anne Carson. For me, her Autobiography of Red, a modern setting of the myth of Geryon and Hercules, is the most original and strangely beautiful verse rooted in antiquity since Pound’s canto 17.

There’s no scope here to survey the random range of contemporary poetry, except to point out there are no notable movements afoot. Quantities of confessional verse in the style of Robert Lowell continue to pour forth, but most of it is composed by poets who have scarcely a passing acquaintance with the tradition they follow, so it can only be trite, regardless of how deeply felt and artfully executed. William Carlos Williams has a lot to answer for, too: small presses and blogs bring out hundreds of tiny poems that humbly offer a single, tiny image, perfect replicas of Williams’ style in the 1930s, typically culminating in a modest, haiku-ish aperçu. They constitute a chat room more than a movement.

The motto of these poets might be, “Keep it the same.” They do no harm, but they’re also on the wrong side of history. Poetry got its numen when civilization began, because the mass of people wanted to hear the bards sing; now no one is listening. Whereas the scandal created by Pound’s Bollingen prize stirred hot passions more than sixty years ago, what passes for a scandal in poetry today is dirty campaigning for a university post, as when Ruth Padel resigned the chair of poetry at Oxford, admitting that she had circulated old gossip about her main rival, Derek Walcott, concerning an alleged sexual misconduct. It was a colossally insignificant affair. Time magazine put Robert Lowell on the cover in 1967: what poet today would be considered for its cover?

One might put the blame on the Internet, as a previous generation tried to fix the blame for a perceived cultural decline on television. Another might bewail the decline of classical education as the beginning of the end. I fix a portion of blame on the decline of middlebrow culture.

Pound believed, literally, that if everybody learned to read the Odyssey, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and Dante, an earthly paradise could flourish. The dream wasn’t as quixotic then as it sounds now. Before the change, self-improving middle-class people went to extension classes to learn the “appreciation of poetry.” Children read Classics Illustrated comic books, and their parents had Mortimer Adler’s Great Books on the shelf, as much to admonish as to inspire. Commercial publishers produced trade books with titles like A Reader’s Guide to James Joyce. In the 1960s, this mainstreaming of high culture was contemptuously batted down by elitist critics such as Dwight MacDonald; by century’s end, any serious scholar who got mixed up in such middlebrow goings-on ran the risk of being branded a popularizer and thrown out of the guild.

However it happened, the thread has been snapped, and the process appears to be irreversible. Mother Goose doesn’t tell us why Humpty Dumpty had a great fall, only that he couldn’t be put together again.

Pound predicted this gathering gloom, a new Dark Age brought on by the rise of commercial mass production, in his pre-Cantos masterpiece, Hugh Selwyn Mauberley. The poem is a tour de force of laminated irony, but this passage comes close to the poet’s views:

All things are a flowing,

Sage Heraclitus says;

But a tawdry cheapness

Shall reign throughout our days.

Even the Christian beauty

Defects—after Samothrace;

We see τò καλóν

Decreed in the market place.

Poets have accepted the New Normal with dismaying docility. After Pound, anyone aspiring to be a poetic messiah would be shunned as a charlatan, like in “The Grand Inquisitor,” the “poem” by Dostoevsky’s Ivan Karamazov, in which Christ returns to Earth during the Spanish Inquisition and is condemned to burn as a heretic for the menace he poses to the church founded in his name. After Pound’s perceived failure, poets aimed low. With the decline in the general readership for poetry, even the precarious bohemian poverty of Pound’s generation was no longer an option, validating in one sense at least the advice of Mauberley’s Mr. Nixon to the young writer, “And give up verse, my boy, / There’s nothing in it.” Poets now polish their CV’s and grant applications as well as their verse.

Change is the only constant, aphoristic Heraclitus says, and change is painful. The change I am describing has engendered anguished denial and much doing of good. If money alone could “save” poetry, it would be in fine shape. In 2002 the pharmaceutical heiress Ruth Lilly gave an estimated $200 million to Poetry—a preposterous sum—in part because the magazine’s editors had sent her kind rejection letters for her submissions of verse. Prizes and grants multiply, handed out by juries of poets with endowed chairs who take turns at applying for the loot themselves. Publishing on demand has made it easy to produce a good-looking book—never mind if there actually is a demand for it.

Poets are still invited to read at presidential inaugurations, a nostalgic touch. The poem for Barack Obama was composed and recited by Elizabeth Alexander, a Yale professor and winner of many prizes and fellowships, a distinguished poet few people had heard of before the inauguration and few remember a year later. At John F. Kennedy’s inauguration, Robert Frost mumbled and lost his place, but he radiated numen. He was as famous as the young president. Everyone in the audience knew that home was the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.

Where do poets go now to be taken in? Borges’ ficción concludes, “In the Deserts of the West, even today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars.” The ruins inhabited by contemporary poets are a serene cloister, immured from the noisy strife of the world, as carefully tended as any graveyard.