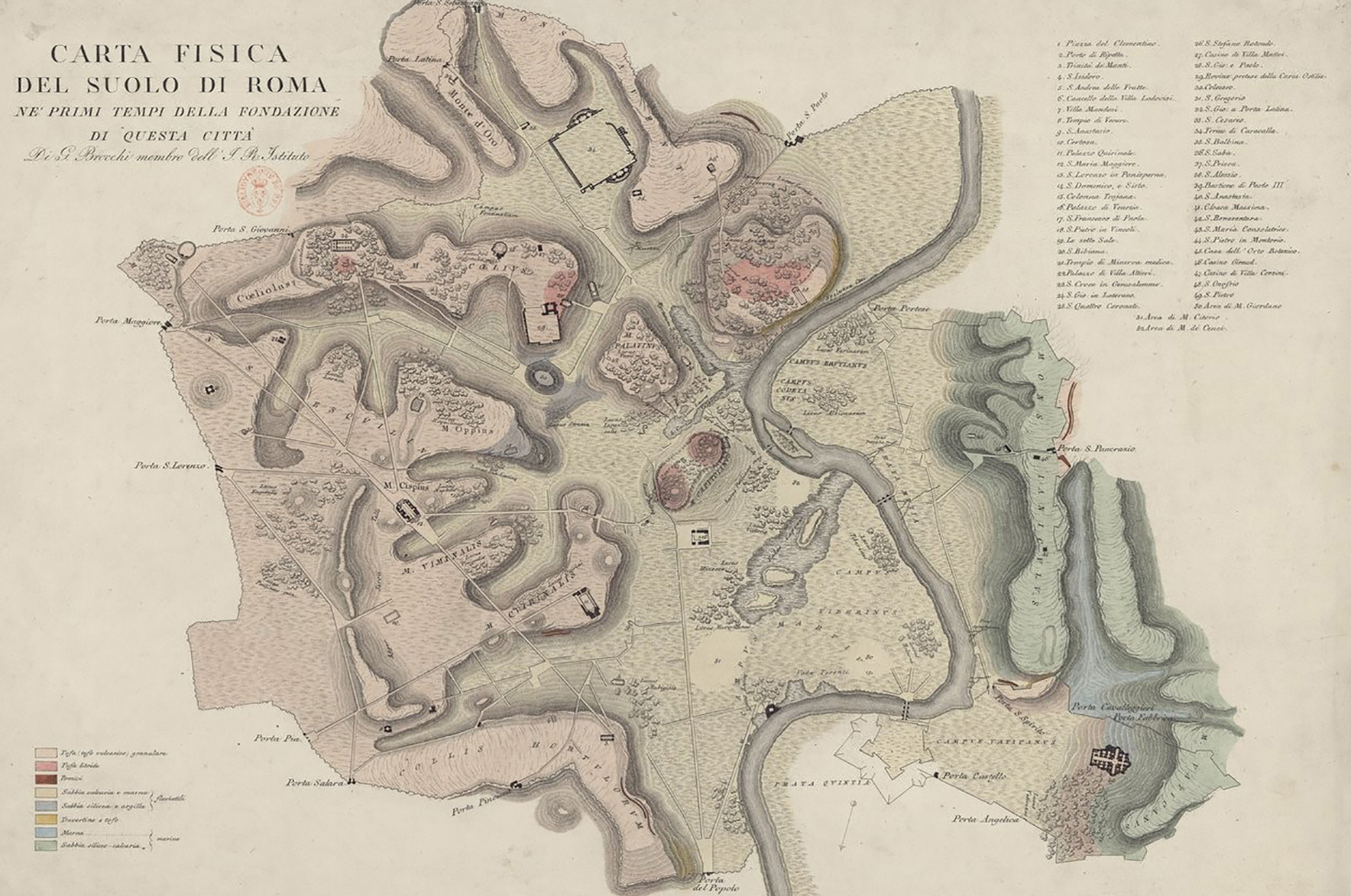

Carta fisica del suolo di Roma ne’ primi tempi della fondazione di questa città (Map of Rome from the early days of its founding), by Giovanni Battista Brocchi, 1820. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Until just a couple of centuries ago, many cities owed their shape and much of their identity to defensive walls. These ostensibly utilitarian structures were often the most meaningful and prominent urban symbols: nothing less than the threshold between inside and outside, self and other. Over the last couple of centuries, their role has faded. Many historical European cities traded their walled fortifications for ring roads as the era of siege warfare gave way to the era of the automobile—Vienna being perhaps the most famous example. Rome, by contrast, has kept its crisp edges intact for the better part of eighteen hundred years.

The Aurelian Wall has remained a benchmark of the city’s rising or falling fortunes for almost two millennia. Much more than just a physical attribute, it is key to Rome’s history and image. Even Rome’s legendary founding hinges on the laying out of walls. As recounted by a number of ancient writers, including Livy, Plutarch, and Varro, the story goes something like this: Rome was established after the fatal conclusion of a feud between Romulus and Remus, twin sons of the god Mars and descendants of Aeneas, the prince of Troy who had fled to ancient Latium following the burning of his city. This duo was a bit like a pagan Cain and Abel. As babies, Romulus and Remus had been abandoned to their fate near the banks of the Tiber. There, a fierce she-wolf discovered, suckled, and protected them until they were taken in by a shepherd and his wife, who raised them as their own.

As young men, the twins decided to establish a new city but argued over where to locate it—Romulus favoring the Palatine, Remus the Aventine. They resolved to settle the matter through augury, a form of prophecy relying on the observation of birds in flight, but quarreled over how to interpret the results. According to Livy’s version of the story, tensions mounted until Remus, taunting his brother, leapt over the provisional wall that Romulus had marked out on the Palatine to define his new city. In revenge for that affront, Romulus killed his brother, named the city in his own honor, and made himself its king.

Tradition dates this fateful sequence of events to a single day: April 21, 753 bc. Whether there is a grain of historical fact at the heart of this fable is the subject of some debate, but there is no denying the crucial role of walls in Rome’s mythical origins. When Romulus outlined the path of his enclosure, he created a sacred precinct: one that no man could violate without consequence. The physical form that Romulus was said to have given his new city was rectangular, dubbed by later generations Roma Quadrata. Even if no undisputed material evidence of this legendary perimeter has come to light, it has been equated with Rome’s earliest identity as an independent city.

Rome’s subsequent history can also be tracked with reference to its walls. Livy and others relate that Rome was ruled by kings until 509 bc, when the citizens rose up to overthrow their rulers and institute a republican form of government. During its first few centuries, the city fused with other hilltop settlements and consolidated its power over the surrounding region of Latium, expanding in terms of population, surface area, and infrastructure. As Rome outgrew its epicenter on the Palatine, it also outgrew its original wall.

Rome’s second, larger defensive circuit, the so-called Servian Wall, dates to the fourth century bc, although its name and possibly its original outline derive from the time of King Servius Tullius in the 500s bc. According to Livy, the Servian Wall was built in the wake of Rome’s brutal sack by the Gauls in 390 bc—an event that made it all too clear that the city was vulnerable to foreign incursion. Constructed out of local tufo (or tuff, a strong but lightweight volcanic stone, easy to quarry and widely used in Roman building projects), its circuit spanned almost seven miles, enfolding all of the seven hills. Unlike Romulus’ wall, which has left scant if any traces in the modern city, we are on solid archaeological footing with the Servian Wall, impressive tracts of which still exist in Rome’s eastern and southern zones. Remarkably, one section can be seen inside the McDonald’s at Termini train station, in a surreal fusion of ancient stone and modern fast food.

Another half millennium would elapse before the construction of Rome’s third and final city wall. Over that time, the city changed a great deal. Already by the third century bc, Rome was capital of a republic that dominated the Italian peninsula and was expanding its territorial holdings throughout the Mediterranean. When Julius Caesar initiated the empire two hundred years later, Rome was the largest city in the world, highly organized and functional, with a population of more than one million.

Augustus, who ruled from 27 bc until his death in 14, famously claimed he had found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble. During his long, stable rule, the city gained a glittering monumentality to match its international stature. Traces of that golden age still exist in monuments like the Ara Pacis and the Mausoleum of Augustus, as well as in many of the obelisks that dot the city, which the emperor looted from Egypt to adorn his capital. Conspicuously absent among Augustus’ many urban embellishments is a new and improved wall. The Servian circuit was becoming a relic of a previous age, having long ago lost its usefulness as a nominal boundary. Since its construction, the city had overrun both sides of the Tiber, and its population had increased more than twenty-five-fold. Despite this rampant growth, the Servian Wall was not replaced until the waning years of the empire in the late third century.

Why? In short, a city that needed walls was vulnerable. For centuries, Rome’s security had been ensured not by any tangible defensive structure but rather by the vast, buffering limits of its own empire. Insulated by its territorial holdings and watched over by its formidable army, Rome was stable, thriving, and impervious. Who needed walls? Only when infighting and external threats seemed poised to end the long-standing Pax Romana (or Roman peace) did new defenses become necessary.

Built by Emperor Aurelian in the 270s and significantly raised by Honorius in the early 400s, Rome’s third and final wall is a formidable chain of brick-faced concrete curtain punctuated by city gates and watchtowers that runs an eleven-mile circuit and reaches a height of some fifty feet. Paradoxically, Aurelian’s wall was not a sign of strength but of weakness, built because Rome had become susceptible to invasion by barbarians from the north.

Another threat was internal. The emperor had just quashed a rebellion among a large swath of city workers, and he might have hoped that a massive building project such as a defensive wall would help to employ and placate the masses, while also serving as a show of force to all classes of potentially unruly citizens. On a symbolic level, as a sign of imperial power, Aurelian’s wall faced inward as well as outward—for it cast its long shadow on restive Romans and outsiders alike.

Whatever the initial reasons for its construction, Rome’s wall has lived an exceptionally long life, but it has hardly remained the same. Some changes have been major—such as the building of the Leonine Wall around the papal enclave in the Vatican during the ninth century—but countless other incremental interventions were necessary to keep the Aurelian Wall standing. Over time, it has been damaged, repaired, expanded, or added to in spots, and updated here and there in response to changing military technology, but like the city itself, it has withstood the test of time. In fact, the Aurelian Wall has been one of the few constants in a place defined by flux. The unceasing attention and upkeep it has demanded and received stands as a barometer to the status of Rome itself: the city as an ongoing process.

During the Middle Ages, the city shrank away from the Aurelian circuit, then, in modern times, burst out of it—outgrowing the wall so dramatically that it no longer demarcates Rome from non-Rome as it once did. The wall is also more permeable than it was in the past, and certainly does not serve its original defensive purpose, but its form remains a signature Roman imprint. Like the omnipresent “SPQR” that stands for “Senatus populusque Romanus” (The Senate and People of Rome)—an inscription that adorns Roman manholes, lampposts, and fountains to this day but has not really been relevant since the end of the republic in the first century bc—the wall has been repurposed as an emblem of the Eternal City.

Published in 1820 as part of a larger volume on the city’s underlying terrain and geology, Giovanni Battista Brocchi’s map depicts Rome’s very ground and topography as it was “in the early days of the city’s foundation.” Brocchi was attempting a pioneering geoarchaeological study: a reconstruction of Rome’s surface features (altitudes, plains, marshes, slopes, etc.) at the time of its mythical origins in the eighth century bc. Using the highly accurate measurements executed by Giambattista Nolli for his plan of 1748 as a point of departure, Brocchi then extrapolated backward in time by incorporating his own geological samples and observations on what lay beneath Rome’s accumulated layers.

Why were such calculations even necessary? We tend to think of natural features like hills and valleys as being relatively immutable—or only changing in “geological” time, over hundreds of thousands, even millions of years—but in fact Rome’s ground level has risen considerably in less than three millennia, in some places by dozens of feet. This dramatic change is due to a combination of natural phenomena, like silting and erosion, and man-made factors, like the Roman habit of building new constructions on top of earlier ones, or creating huge trash heaps—like Monte Testaccio, a mountain of discarded amphorae (oil jars)—that eventually became lasting parts of the urban topography. Brocchi’s image depicts the physical setting for the city’s long history of human settlement, but even that setting was not fixed, for it evolved considerably over the centuries.

That said, Brocchi’s image neatly encapsulates Rome on the verge of becoming itself. Before there was a city called Rome, there was a place: a stage waiting for its actors and script. Books have been written on this locale, as if to make sense of how such an unremarkable site could give rise to such a remarkable history. At its heart is a bend in the Tiber River, a serpentine curve, at the hinge of which the river widens, making room for a small island believed to have been the city’s first site of human habitation. Nestled within the northern loop of the Tiber’s curve is a low-lying floodplain, which later became known as the Campus Martius—Campo Marzio in Italian, or Field of Mars. This zone appears toward the bottom of Brocchi’s map, oriented as it is with north at the bottom. Above it, on the other side of the river, the southern loop contains the zone that would later become known as Transtiberim (literally, “across the Tiber”; today’s bustling Trastevere).

For anyone who knows Rome even a little bit, it is all but impossible to look at a blank stage like Brocchi’s without mentally filling in the later additions. The Pincian Hill is the site of today’s Villa Borghese park; the Vatican, world capital of Catholicism; the valley between the Capitoline, Palatine, and Esquiline, home to the Roman Forum; and so on. If you look closely at Brocchi’s map, you will see that he too could not resist the impulse to insert later history, for he portrays a handful of Renaissance streets and landmarks, ancient monuments, and churches from the Middle Ages on.

Most notably, the map employs the Aurelian Wall as a framing device, using it to hem in the whole image, thereby defining Rome’s artificial boundary as if it had been there all along: Rome’s version of Manifest Destiny. Brocchi clearly included the wall, like the other anachronistic features, as a key reference point. After all, without its distinctive enclosure, the map could almost be mistaken for any arbitrary assemblage of hills, plains, and river. The lightly outlined presence of the Aurelian Wall signals that this is not just a random slice of topography: it is Rome.

Reprinted with permission from The Eternal City: A History of Rome in Maps, by Jessica Maier, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2020. All rights reserved.