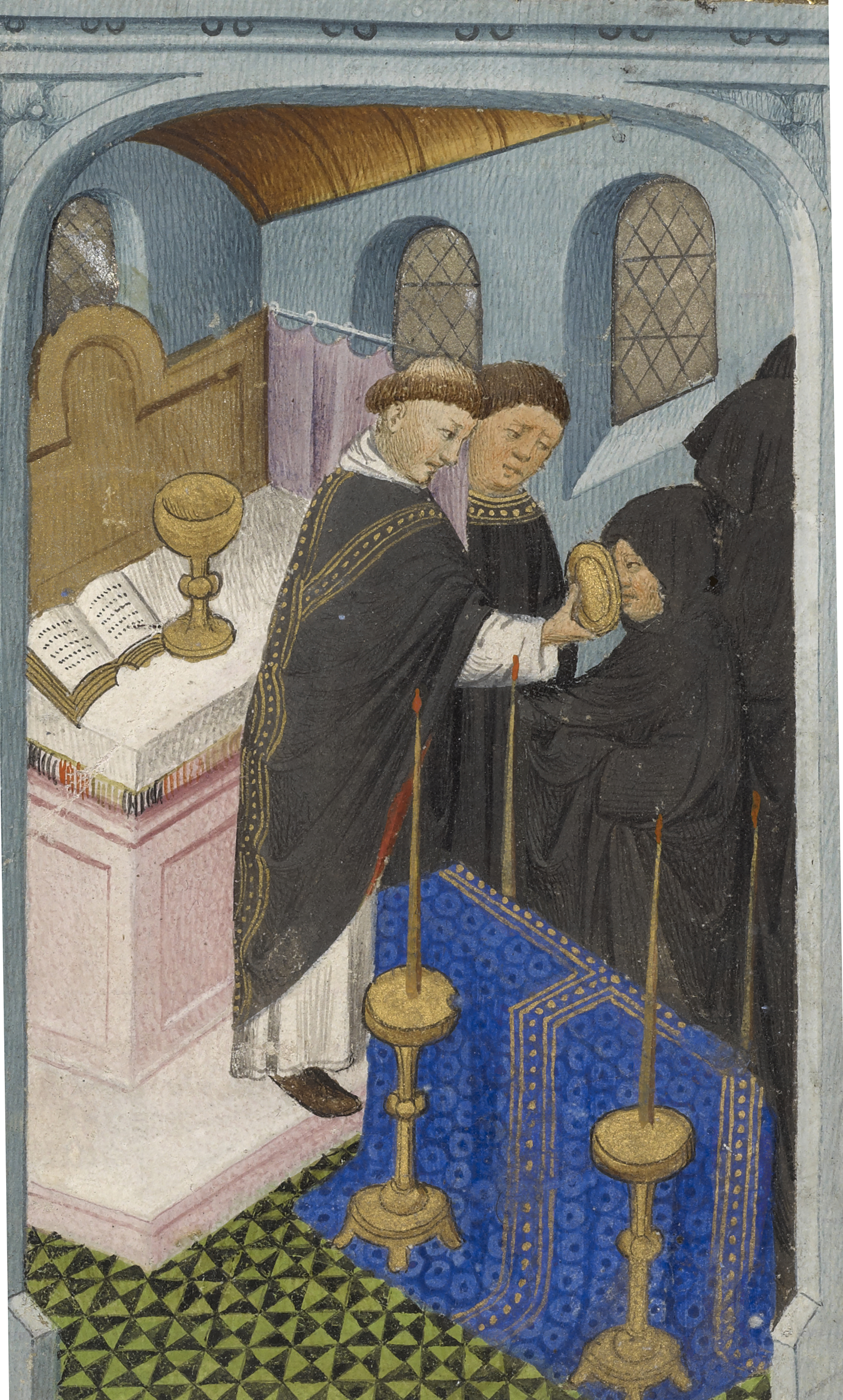

Mass for the Dead, France, c. 1410. © The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

A message opens with news of “a disaster.” Its writer warns of “lethal plague” spreading fast and moving north. The missive’s recipient, an administrator in a city more than three hundred miles away, is advised to immediately block off the roads and halt travel to and from his city. Yet both parties know this will not be a popular action; the weather has warmed, and people are eager to leave town for annual celebrations. They are likely to defy any travel restrictions. How can they be stopped?

This epistolary quandary wasn’t penned at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, nor during the 1918 Spanish flu. It precedes even the Black Death, when it is commonly reported that quarantines, or cordons sanitaires, and travel restrictions originated. When the bubonic plague overwhelmed Europe in the middle of the fourteenth century, it resulted in the deadliest pandemic in recorded history, killing off an estimated fifty million people, or between 30 and 60 percent of Europe’s population. As cities scrambled to find ways to isolate the sick from the healthy, they were said to have created many of the public health measures we still rely on today. Yet a message exchanged in 640 between two bishops in what is now southern France provides a glimpse of early medieval travel restrictions, evidence that humans had a more nuanced understanding of how to fight pandemics much earlier than is commonly assumed.

By 640 the world had been battling bubonic plague for a century. The disease had originated in central Africa, made its grand entrance in the Egyptian city of Pelusium, and then, in the spring of 542, was unleashed in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire. The people of the sixth century were inured to deadly outbreaks—smallpox, cholera, dysentery—but this one upended all of their understandings and expectations of illness. The disease began innocently enough, with a mild fever. Byzantine historian Procopius, writing in the years after the plague first arrived, noted that “not one of those who had contracted the disease expected to die from it.” But very swiftly thereafter, pus-filled boils formed in the lymph nodes—the buboes from which the disease would later take its name. The outbreak was soon termed the Plague of Justinian after the ruling Byzantine emperor at the time, who was himself was stricken. Although Justinian managed to recover, most others did not. Procopius claimed that the daily death toll climbed exponentially, first averaging five thousand and then surpassing ten thousand deaths in a single day. Another eyewitness claimed those assigned to count the bodies gave up when they reached 230,000.

The plague raged in Constantinople all throughout the summer of 542, and then it tapered out. On March 23, 544, Justinian naively declared the plague over. Yet bubonic plague would circulate for the next two centuries and cause at least eighteen major known outbreaks.

The first reaction to the plague’s appearance was, quite naturally, shock. Yet despite the general chaos, there was an attempt to use reason and observation to get a handle on the pandemic. In the earliest months of the outbreak, physicians tried lancing buboes to see if they offered any clues. And while doctors could not pin down the exact vector spreading the plague (infected fleas), the early medieval world quickly grasped the basics of the disease’s transmission. Accounts by two survivors of the first wave of plague make it clear that even common people understood that boats spread sickness.

Procopius, writing around 550, observed that the plague always seemed to start from a port city and then spread inland. The historian John of Ephesus, writing a decade later, relates local superstitions about magical disease-bearing ships populated by headless demons. As the plague ricocheted around Asia Minor and Persia, and then spread to Europe in the decades that followed, it became clear that it was not the boats themselves but the things they carried—infected merchandise and people—that were spreading the disease. Gregory of Tours, a Frankish bishop and historian, describes how one outbreak in Marseilles started with a single ship from Spain that carried “the seed of this disease.” The sailors took sick, then the tradespeople who had greeted them, then their families, and then their neighbors, until “like a cornfield set alight, the entire town was suddenly ablaze with pestilence.” Gregory even uses the Latin contagio, a word derived from the verb to touch, in making explicit his understanding that the disease was spread through contact.

Despite the knowledge that travel and close contact spread the plague, many political leaders ignored the science of the day. Some stubbornly insisted on large gatherings, orchestrating early medieval “super-spreader” events. One king ordered his far-flung people to assemble in a cramped city church for a religious rally to prop up his ego; elsewhere a new pope organized a citywide penitential procession in an effort to attract God’s mercy, during which eighty people collapsed. Given such uneven leadership, many people became fatalists, figuring that there was no reason to take action when everyone would get the plague in the end. Others flocked to folk remedies and miracle cures. One such treatment originated when a resourceful mother secretly ripped a piece of fringe from the king’s robe, soaked it in water, and had her sick son drink the concoction; it was reported that immediately after, his fever broke.

In 640 the eighth wave of the Plague of Justinian was under way. This bout had surged in Amwas in Syria during the Muslim conquest of the area. It then made its way by boat to the bustling cosmopolitan port of Marseilles. From Marseilles the plague moved inland, spreading through Provence. Observers feared it would, as before, continue its onward march, especially if people refused to stop traveling. As Bishop Gallus II sat down to write to Bishop Desiderius, he had good reason to be concerned.

Most of what we know about Gallus II comes from this letter. In contrast, his colleague Desiderius is one of the best-documented men of the seventh century. We know that the fifty-year-old Desiderius had received a classical education, spent a great deal of time at the royal court, and was both well connected and fabulously rich. Both men presided over cities in the Frankish Empire and, at least in the eyes of the church, were considered equals. Gallus II was the bishop of Clermont, a former Roman stronghold; Desiderius was the bishop of Cahors, a prosperous river port 150 miles to the southeast. Both cities fell within the diocese of Bourges, which had been hit especially hard by a 571 outbreak of the plague. “There was such a shortage of coffins and tombstones,” Gregory of Tours wrote, “that ten or more bodies were buried in the same grave. In St. Peter’s Church alone on a single Sunday three hundred dead bodies were counted.”

Church administrators observed that their piety conferred no special immunity. Despite the usual prayers, fasts, and vigils, one of Gallus II’s predecessors had been struck down by the sickness—and on Good Friday to boot. A prominent abbot and priest soon followed him to the grave.

But the institutional memory of the church stretched back further than that of the public. Seventy years after the last plague outbreak, Cahors had not only recovered but prospered. Its merchants and tradespeople now had disposable income and, presumably, a taste for the finer things in life. Because of these circumstances, Gallus II seemed particularly concerned that Desiderius’ flock might put personal pleasure over the common good. They might defy the travel restrictions to leave for “celebrations in La Rouergue or the neighboring cities,” he wrote to Desiderius, likely referring to a festival for Saint Quintian of Rodez, whose feast day fell on June 14. The weather was clear; the flowers were in bloom; and after the processions and prayers were concluded, there would be the opportunity to feast with family, mix with eligible singles, and do a little buying or selling at the fairs. When the people returned to Cahors after the festivities, they would likely bring the plague back with them.

And who could stop them?

During the various waves of plague, bishops were uniquely positioned to affect public health policy. Church leaders generally came from old, established families; were independently wealthy; and, ever competitive with secular authorities, were used to undertaking large civic works programs. Francia lacked a centralized authority and was deeply divided. At various points, the empire had been partitioned into as many as four separate subkingdoms, each with its own cumbersome bureaucracy. Now the empire was split, with one part nominally ruled by a nine-year-old and the other under the dominion of a seven-year-old. The regions afflicted with plague were spread across these two kingdoms. Given this fractured secular authority, the church saw an opportunity to further legitimize and consolidate its authority. But it still had to reckon with its own complicated hierarchy. Travelers heading from the epicenter of the outbreak in Marseilles to Desiderius’ city of Cahors would pass through at least a dozen bishoprics and four different dioceses, each with their own tangled internal politics.

Yet even under these conditions, a large-scale response had already been coordinated. Gallus II reported to Desiderius that “guards have been stationed throughout the regions which border those parts [Provence], so that absolutely nobody may have the chance to buy or sell.” He begged his fellow bishop to do the same: “My Lord should take steps to send guards and prevent anyone from Cahors from taking it upon himself to leave.”

The matter-of-fact tone and brevity of Gallus II’s message—a mere five sentences—conveys that both bishops understood how the plague was spread. All that remained up for debate, as it still does now, was how best to implement the restrictions. Gallus II warned Desiderius that it was not enough simply to discourage or advise; one had to “ask these measures to be strictly enforced.” If not, “the danger of death” would loom over his city.

This letter is our only evidence that quarantine measures were employed in Europe prior to the fourteenth century. As such, it offers a tantalizing peek at a body of scientific knowledge that has otherwise been lost. It also fits in neatly with a larger conversation between bishops about public health and safety. Around the same time church officials exchanged correspondence about securing clean water for their cities in order to prevent illness. Desiderius had written to Gallus II’s predecessor for help restoring the underground water pipes in Cahors. We also know that bishops oversaw travel between territories—another of Desiderius’ letters arranges safe passage for one of his priests. So bishops in this period were already concerned with combating disease and uniquely positioned to regulate the movement of people and goods. Implementing travel bans in the midst of pandemic was a logical extension of the bishops’ established authority.

The lack of any similar public health directives does not mean they did not exist, merely that they do not survive. It is important to note that the early medieval period is “dark” of sources, but not because people were not reading and producing them. This time period straddles the shift from one writing medium to another. The papyrus imported from Egypt easily deteriorated in the cold and humidity of Europe, while the parchment from animal skins that later dynasties would use did not.

The monk who dutifully recopied Bishop Gallus II’s letter onto parchment in tight, tiny script unknowingly ensured its survival for the next thirteen hundred years. Yet that was only the first step. After Desiderius’ death, sixteen of his letters and twenty-one missives he received, including Gallus II’s, found their way into what appears to be a style manual for correspondence among elites in a monastery’s archives. This collection was later compiled with other religious works—including letters and sermons by Saint Augustine, an apocryphal book of the Bible, scraps of work by Isidore of Seville, and a strange benediction for bees—which led to it being recopied again and again, surviving to be found by scholars today. In the style manual, writers showcase their literary prowess with classical allusions and alliterative passages, as well as provide examples of thank-you cards and apology notes. That this letter was included is suggestive in itself—was Gallus II’s message to Desiderius just an example of a typical message about commonplace plague precautions?

It’s unlikely that church-enforced travel bans were an anomaly. There is evidence that similar bans had been put in effect by Muslim leaders in the Middle East. More than one scholar has speculated that if a fractured Frankish Empire could manage to employ such practices, surely other, more sophisticated states could as well.

In the years following Gallus II’s letter, there is no record of serious illness in either his or Desiderius’ dioceses. In fact, there are no instances of the bubonic plague anywhere else in the Frankish Empire. The next big outbreak in 664 decimated England, but its close neighbor and trading partner was spared. Another wave in 680 upended Italy but did not spread further north. Because so few sources survive from this era, it is difficult to know whether to ascribe this to dumb luck or some other combination of factors. It’s certainly tempting, though, to see this as a triumph—however fleeting—of reason over magical thinking.