Robert E. Lee monument, Richmond, Virginia, 2020. Photograph by Joseph. Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Criticism of the Lost Cause and Confederate symbols stretched back as early as 1870, when Frederick Douglass called out the “nauseating flatteries of the late Robert E. Lee” that poured in after the Confederate general’s death, asking, “Is it not about time that this bombastic laudation of the rebel chief should cease?” Until his death in 1895, Douglass engaged in an uphill battle to dislodge the Lost Cause narrative that had gripped the national consciousness while still seeking to preserve the memory of emancipation. But the pull of the Lost Cause was strong. Even white Northerners were willing to make a devil’s bargain with the South’s Confederate tradition for the sake of sectional reconciliation. And the race to build “monuments of folly,” as Douglass called them, had yet to peak by the time of his death.

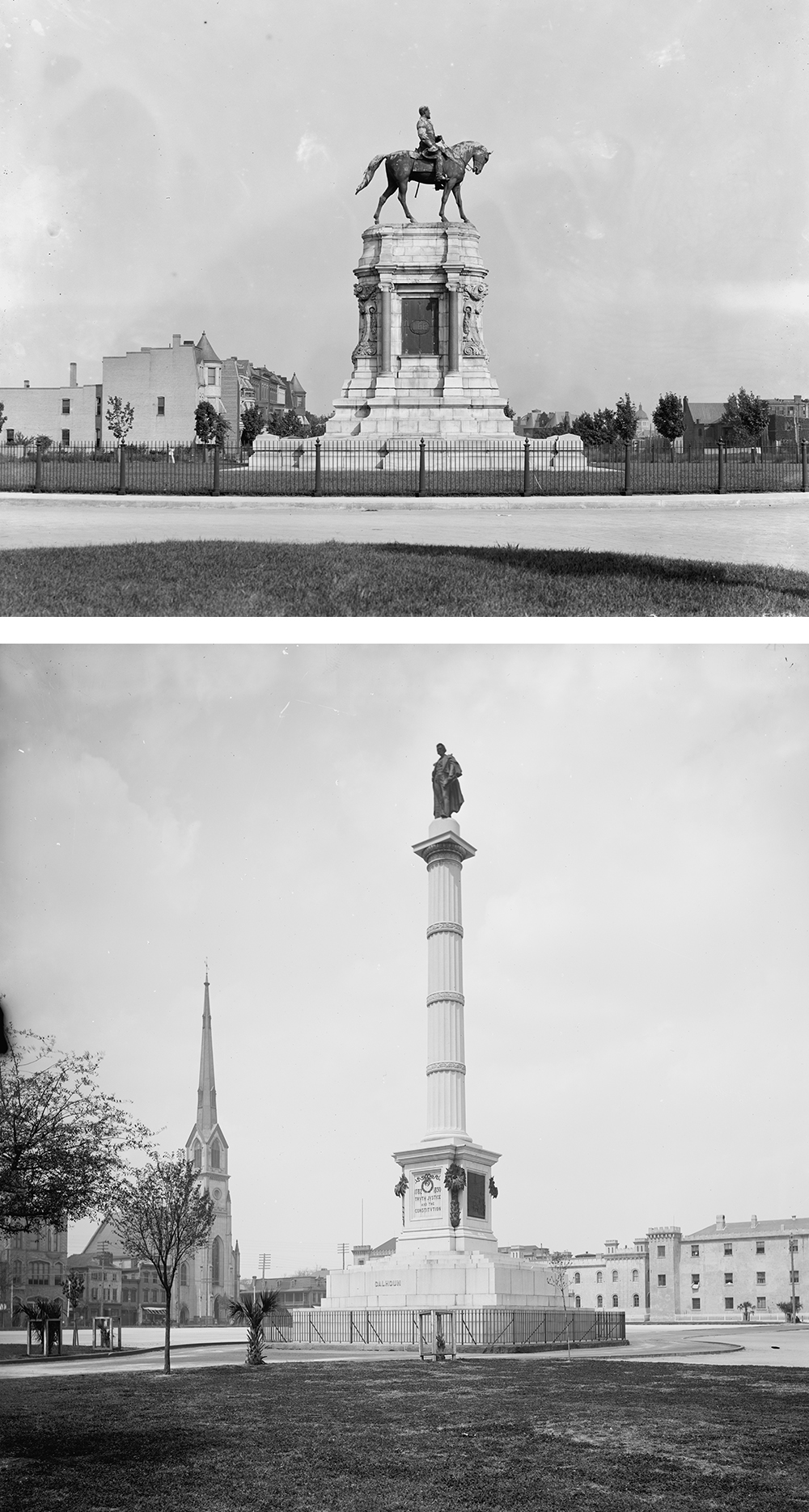

Still, while Frederick Douglass waged a battle against the North’s capitulation to the Lost Cause the rest of his life, the real war against it was in the South, where Black Southerners were on the front lines. They were keenly aware that Confederate symbols in their communities were imbued with racism and white supremacy, and they protested them publicly and privately. Some of the earliest identifiable Southern protests occurred in Charleston, South Carolina, in response to the monument built to honor John C. Calhoun, U.S. senator, secretary of war, and vice president of the United States from 1825 to 1832. Calhoun was also a fierce defender of states’ rights to preserve the institution of slavery. While not technically a Confederate monument—Calhoun died in 1850, long before the South seceded—its unveiling on April 26, 1887, Confederate Memorial Day in South Carolina, and the ceremonies that accompanied it, including the singing of “Dixie,” placed it firmly in the Lost Cause tradition.

From the outset, the Calhoun monument, centrally located on the Citadel Green, was the object of derision within the local Black community. As historians Ethan J. Kytle and Blain Roberts have shown, Black Charlestonians “mocked and vandalized the monument,” as did some white Charlestonians, but for different reasons: whites reviled it for its aesthetics, while African Americans despised it because of what Calhoun represented to their race. As Mamie Garvin Fields, a Black Charlestonian born in 1888, put it, “Since we thought like Douglass, we hated all that Calhoun stood for.”

“We used to carry something with us, if we knew we would be passing that way, in order to deface that statue—scratch up the coat, break the watch chain, try to knock off the nose,” Fields remembered, later adding, “I believe white people were talking to us about Jim Crow through that statue.”

Eventually, city leaders replaced the original Calhoun statue with a new one that rose several feet above the Charleston skyline on a pedestal far out of reach of the kind of vandalism Fields described. While no evidence confirms that the new monument towering over the Citadel Green was constructed in response to vandalism, Black Charlestonians nonetheless took pride in the belief that they caused the change.

Outside of safe spaces like private homes, churches, or a Masonic lodge, the fear of reprisal from local whites prohibited African American adults from making their feelings about monuments public in the Jim Crow South. For example, African American Richmonders held similar views about the equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee in their hometown, which they expressed through the local Black newspaper, the Richmond Planet. When the Lee monument was unveiled in May 1890, the paper reported that “Confederates from New York to Texas” who were in town for the unveiling demonstrated their continued commitment to Confederate values, behaving as if the South had not lost the Civil War. The display of “rebel flags,” including one “mammoth Confederate flag” that covered the entire length of city hall, alongside the gathering of Confederate veterans giving a full-throated “rebel yell…told in no uncertain tones that they still clung to theories which were presumably to be buried for all eternity.” While the paper’s editor, John Mitchell Jr., did not begrudge the entirety of the ceremonies, acknowledging that “the South may revere the memory of its chieftains,” he felt that the region “proceeds to go too far in every similar celebration.” Doing so not only was a deterrent to progress, he lamented, but also “forge[d] heavier chains with which to be bound.”

Barely a week after the unveiling of the Lee monument, Mitchell sounded a different alarm. There was more than just a new statue at issue. In an editorial titled “What of Virginia,” Mitchell warned readers that the rights Black people had won during Reconstruction were being rolled back. He printed the words of the Fifteenth Amendment, which guaranteed the right to vote regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” and pointed out that the amendment was now under attack, adding, “There must be a remedy.”

But there was no remedy in the 1890s South, as states across the region took steps to disfranchise Black voters. And it was not a coincidence that the Lost Cause fed that movement as much as it did the building of Confederate monuments. John Mitchell knew it, as did editors of Black newspapers elsewhere. Two weeks after the Lee monument was unveiled, Mitchell printed a sampling of editorials in a column called “The Voice of the Colored Press,” which detailed African Americans’ concerns about the meaning of the unveiling to their race. “The exhibitions of rebel flags on all holiday occasions in the South is not the only way the people of that section show that they have not accepted the results of war,” a Detroit paper lamented, while a paper from Springfield, Illinois, wrote of the “shameful disregard for the flag of the Union and of higher respect for the flag of treason” during the unveiling of the Lee monument in Richmond. A Baltimore paper cautioned that the celebration of Lee and the Lost Cause served “as an opportunity to justify the rebellion of the Southern people against the U.S. Government and to flaunt the Confederate flag in the faces of the loyal people of the nation” and deserved “serious reflection.” Lee, after all, had “bound himself under oath to support and…extend the accursed institution of human slavery.” From Louisville, an editor was far more pointed in his criticism of the festivities in Richmond. “They hold their lives by the mercy of the nation they attempted to destroy,” he wrote, “and this rehabilitation of the infamous cause of the Confederacy is rank treason.” As Black Southerners throughout the region knew, the rehabilitation of the Confederacy was accompanied by the rise of white supremacy in the 1890s, and monuments were demonstrations of that fact.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, African Americans continued to express their contempt for Confederate symbols. The Chicago Defender, founded in 1905, quickly became a nationally respected Black newspaper, and its pages were a lively space for both journalists and readers to voice their opinion on Confederate flags and monuments. Many of its columnists were migrants from the South, and the paper was read and shared throughout the region.

From the outset, the Defender published pieces that linked monuments to both slavery and treason, and writers were very clear about what should be done with them. A 1920 article about a recently discovered bill of sale for a thirteen-year-old enslaved girl in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, was intended as a lesson to “the younger generation.” The buyer, who could neither read nor write, had signed the document with an “X,” the Defender told readers, “signifying he was ignorant.” Yet it was in the closing paragraph where the paper zeroed in on slavery’s link to the Lost Cause. The story of the sale of a young Black girl, the Defender argued, was “testimony enough to justify the statement that every Confederate monument standing under the Stars and Stripes should be torn down and ground into pebbles.”

The following year, a staff correspondent writing from Thomasville, Georgia, published an unsigned article under the headline tear the spirit of the confederacy from the south—destroy all flags, records, and other symbols of antebellum days. Given the tenor of the piece, it is clear why the author remained anonymous, since revealing his identity (writers at this time in the Defender’s history were male) would have put his life in danger. The article began as a response to protests against a statue of John Wilkes Booth in Alabama that had been placed there in 1906 but had received national attention, including in the Northern press. This monument to the “murderer of the Emancipator” led the author to rail against Confederate iconography in Southern communities and to present a searing critique of the Lost Cause. “In every Southern city, town, or hamlet one sees relics of the Confederacy kept intact,” he wrote. “Confederate flags fly triumphantly, monuments are erected to Lee, the victories of rebels are celebrated, museums gather obsolete weapons, libraries store the infamous records, white school children are studiously taught to believe in the righteousness of the lost cause,” he complained, and all of it was done “to reproduce the spirit of antebellum days.”

The author’s detailed description of Confederate culture in the South, much of it a result of the United Daughters of the Confederacy’s efforts, is a vivid reminder of how widespread the Lost Cause was and how embedded it had become even in communities with a significant African American population. He recognized a direct link between these symbols and the disfranchisement of his race. “Every Confederate flag in the South should be sought out and burned,” he wrote, adding that “it should be made a misdemeanor to display one” and that parades that honored rebels “should be made a crime.” Sectionalism was the problem, he argued, because it “propped up” Confederate traditions. And he pointed the finger at public schools, churches, and newspapers for the “incalculable wrong” they were doing to Black Southerners, especially in public schools, justly noting how the continued instruction of Lost Cause ideals perpetuated racism among the next generation of white Southerners: “The Southern white child goes to school to find an emblem of Jefferson Davis’ South hung beside Old Glory. He is taught that the old ideals are still right…The Southern white child is taught and led to believe that he is a superior being; that the law which granted freedom and opportunity to our race may be easily glossed over; that he does not have to obey it.”

The Chicago Defender regularly engaged its readers, asking them their thoughts about any number of topics that were of interest to the race in a column called “What Do You Say About It?” On September 10, 1932, the paper printed the answers to the question it posed the prior week. The question “Would you favor a federal law to abolish all patriotic monuments erected in the South to the memory of Confederate soldiers?” elicited several favorable responses. Spencer Hilt of Columbus, Georgia, wrote, “I am highly in favor of such a law,” and pointed disapprovingly to the federal government for tolerating “the unpatriotic spirit of the South to the Stars and Stripes.” Hilt added, “Rebels should not be honored, and any section of the country producing traitors should be ashamed of them.” John Upcher, a reader from Omaha, Nebraska, was troubled by what monuments taught young white Southerners. “Every time children of the men [Confederate veterans] look at the monuments it gives them a greater desire to…carry out the wishes of their forefathers,” he worried, adding, “If those monuments weren’t standing the white South wouldn’t be so encouraged to practice hate and discrimination against our people.” In short, he said, “They stand as emblems of hate and envy” and “shouldn’t have been permitted” to be erected. A letter from Scott Boydston of Birmingham, Alabama, began by calling out the Lost Cause: “The dirtiest blot on the pages of American history was written by rebel statesmen of the South. Why honor them?” He suggested that Confederate monuments were the equivalent of one “to the memory of Benedict Arnold.” He believed that the South held the nation back and concluded by writing, “Only fools would want to glorify men who fought in defense of human slavery.”

From No Common Ground: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice by Karen L. Cox. A Ferris & Ferris Book. Copyright © 2021 by Karen L. Cox. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.