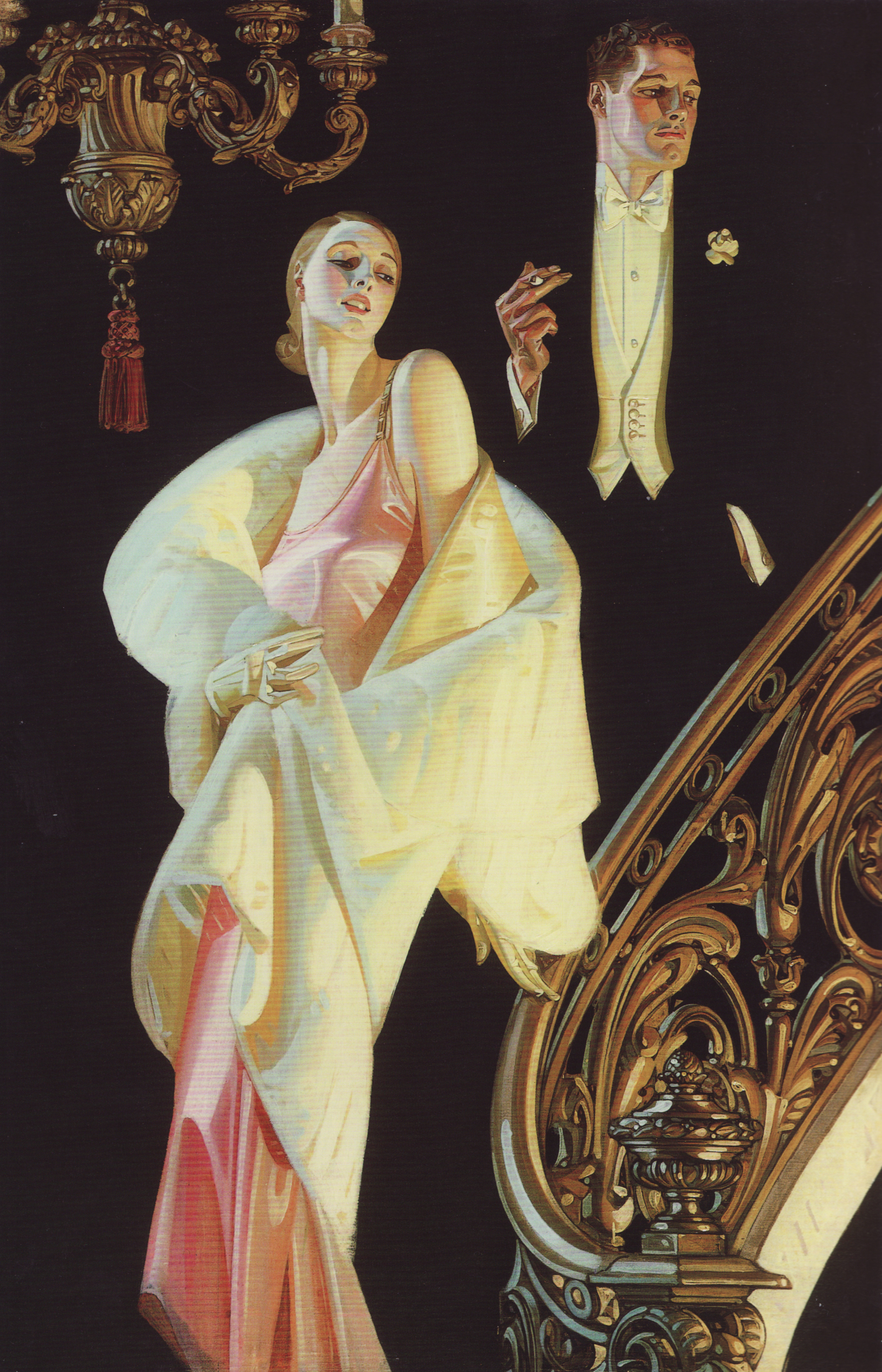

Couple Descending a Staircase, from an Arrow Collar advertisement, by J.C. Leyendecker, c. 1925. Cluett, Peabody & Co.

He stands on a staircase behind his paramour. His hand, hovering in the void where tuxedo blends with room, holds a cigarette as though at any moment he might toss it like a pair of cards into the muck. His bowtie is exquisitely knotted, collar stiff and starched, boutonniere like a white heart newly blossomed on his breast, everything tailored to perfection. He has a strong jaw and a dimpled chin. He looks off into the distance, away from you and away from his lover, too, alluringly unattached. His eyes are lowered, melancholic but without a trace of self-pity.

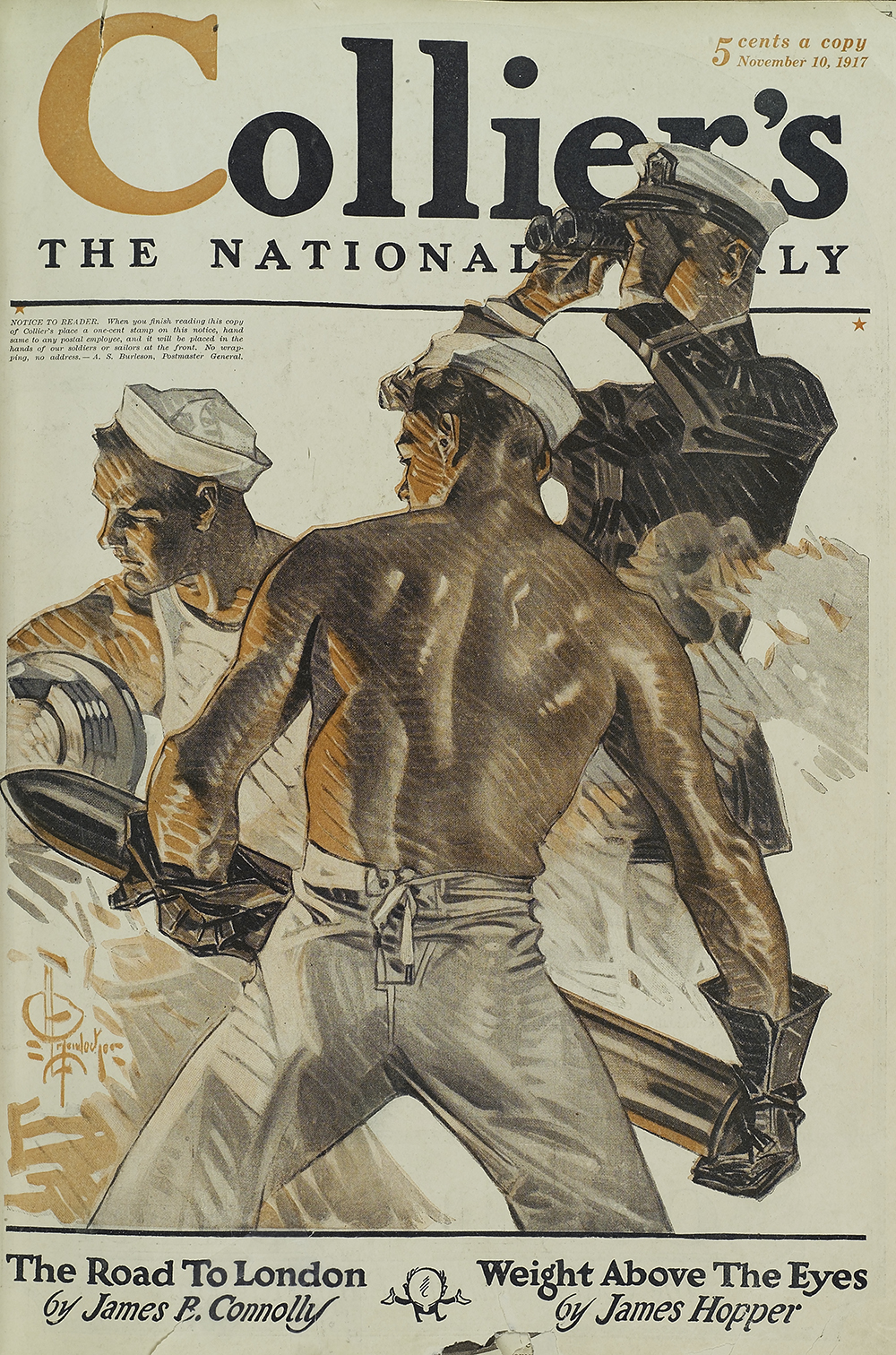

Or: He teeters precariously—one foot on the ground, the other extended in front of him, mid-punt. His hands act as counterweights, balancing him amid the movement. His football pants are baggy at the knees and the hips. His blue shirt’s brown shoulder pads turn his toned if unexceptional shoulders almost Herculean. His eyes remain on the football that he’s just sent sailing through the air. There’s not a hair on his head that’s out of place, despite the movement. His cheeks are rosy—out of red-blooded exertion rather than jejune innocence—yet the whole affair feels unlabored, amusing, fun. The corner of his mouth curls up slightly into an almost grin. He hopes he has just impressed his high school sweetheart, who must be sitting in the stands with her parents. A sea of white crosshatched brushstrokes form a textured abstract backdrop.

Or: He stands upright, in profile, the posture of an educated Jesuit. His military uniform is tan, recently laundered. A satchel hangs off his shoulder, resting at the base of his buttocks. His head is strapped into a Brodie helmet. That brown leather strap is flush to his cheeks and chin, contorting his face uncomfortably. He tries to show no emotion as an older man pins a medal to his breast, but his eyes betray both a sense of pride and a measure of sadness. Yet another honor his fallen brethren will not receive.

He is a Leyendecker Man.

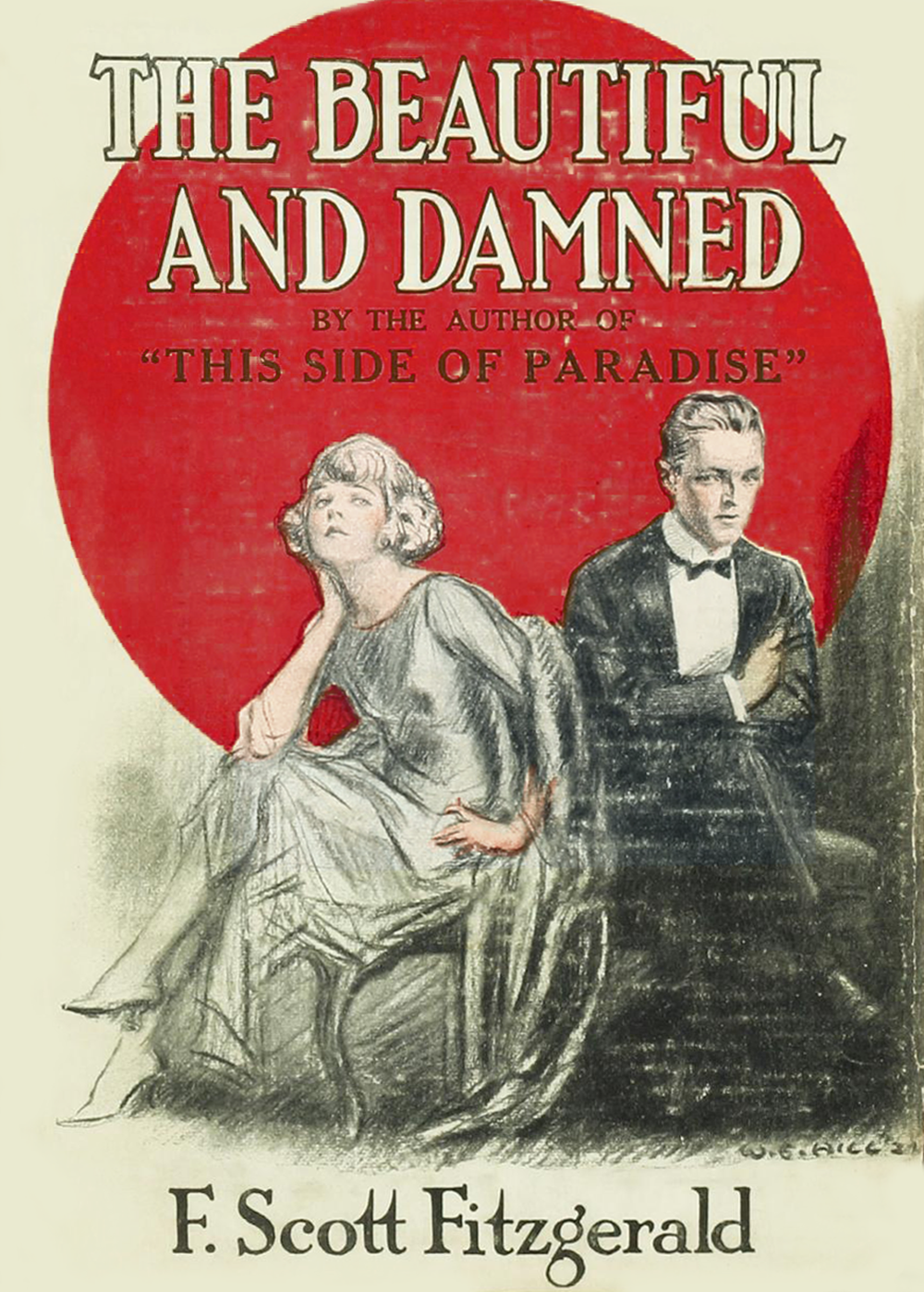

You’ve read of these men in the works of writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. Their heirs are all around you. They are our image of the ideal man in the early twentieth century. Fitzgerald and Hemingway may have written the words that helped define American masculinity in the first half of the twentieth century, but it was J.C. Leyendecker who gave us (and them) the iconography.

No standalone biography of Joseph Christian Leyendecker exists. There hasn’t been an in-depth critical study of his work either. Much of what has been said about him is incomplete, embellished, or false—more hearsay than fact, written in whispers. Like the men featured in his art, Leyendecker’s life has become a series of crosshatched brushstrokes on which, for better or worse, we can impose our own interests and biases. Though he is undoubtedly one of the most successful and influential commercial artists of the twentieth century, there have been only two books that focus solely on him. The first, an art book published in 1974, features a short introductory text by Michael Schau that is riddled with inaccuracies.1 The second, J.C. Leyendecker: American Imagist by Laurence S. Cutler and Judy Goffman Cutler in association with the National Museum of American Illustration, was published in 2008. It has a brief biographical sketch of Leyendecker, which corrects many of Schau’s mistakes, as well as some analysis of the illustrator’s work and methods.

The artist was born to Peter and Elizabeth Leyendecker on March 23, 1874, in Montabaur, a small town between Frankfurt and Cologne in western Germany. In 1882 the family—his parents and three siblings—emigrated to Chicago, where his father went to work for the McAvoy Brewing Company.

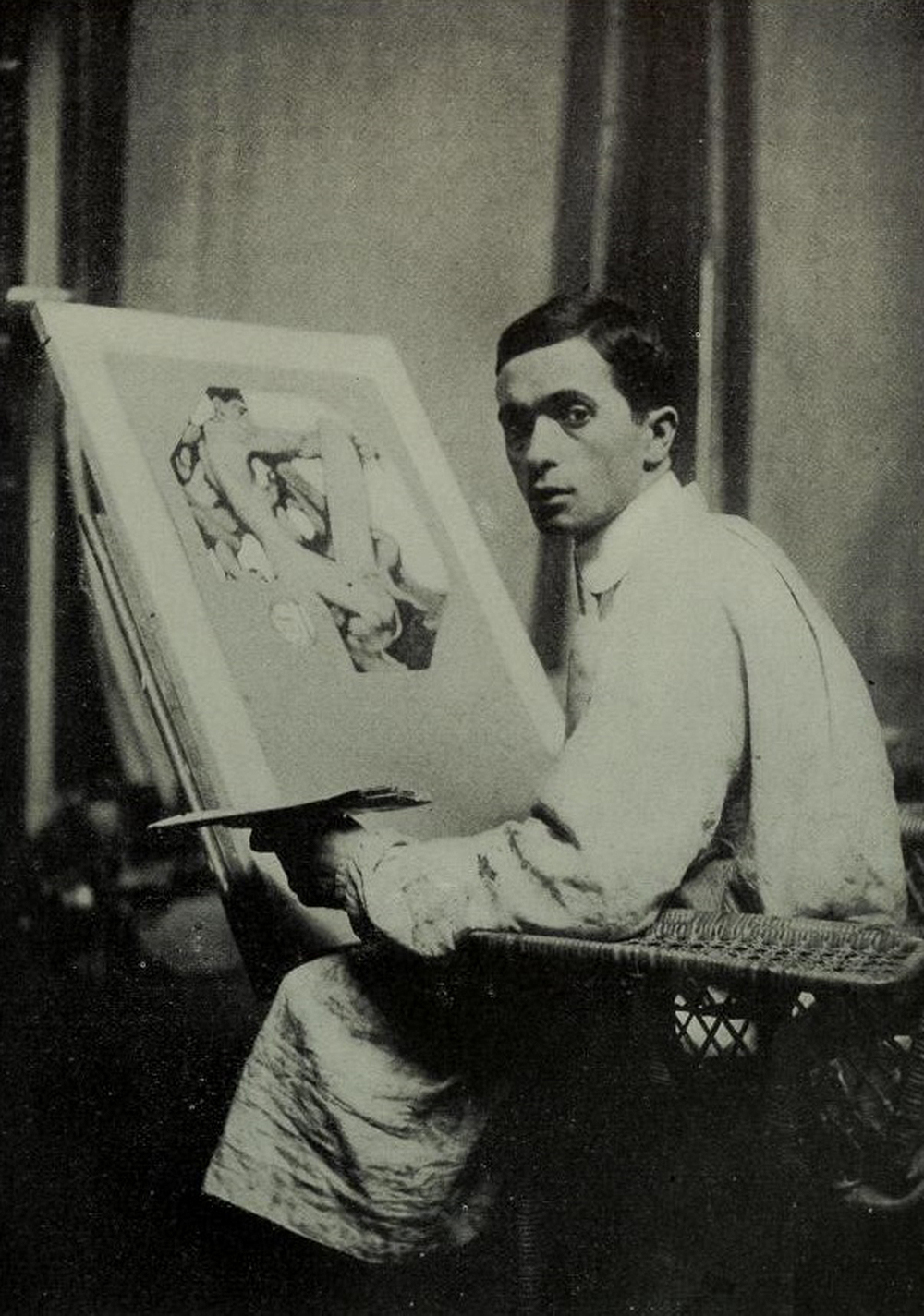

As a young man, Leyendecker was hired as a staff illustrator at the engraving firm J. Manx & Company and attended the Art Institute of Chicago. He gained significant exposure after winning first prize in a cover design contest for the immensely popular magazine The Century in 1896. Later that year, Leyendecker made his way to Paris to study at the Académie Julian, younger brother Francis Xavier, also an artist, in tow.

Soon after the brothers returned stateside, J.C. Leyendecker received his first commission for a Saturday Evening Post cover in 1899. Thus began his nearly half-century association with the country’s most popular magazine. He produced 322 covers for the Post, the most covers for that magazine by any artist—one more than Norman Rockwell. (The rumor is that Rockwell stopped at 321 in deference to his idol.)

Leyendecker developed his idiosyncratic style early on, focusing on attractive subjects rendered with an academic realist’s understanding of the human body, an impressionist’s play with light and color, and an engraver’s crosshatching line technique. Laurence S. Cutler and Judy Goffman Cutler write that “he invented and popularized the exaggerated, quick brushstroke effect known as pochet, or crosshatched strokes with oil paint.”

There were many Leyendecker copycats. Rockwell was only the most successful of them. Looking back at the archive of Saturday Evening Post covers from the first half of the twentieth century, or glancing through almost any magazine with illustrated stories or advertisements from the period, one finds pages populated with Leyendecker-esque figures created by artists about whom we know even less than we do about Leyendecker.

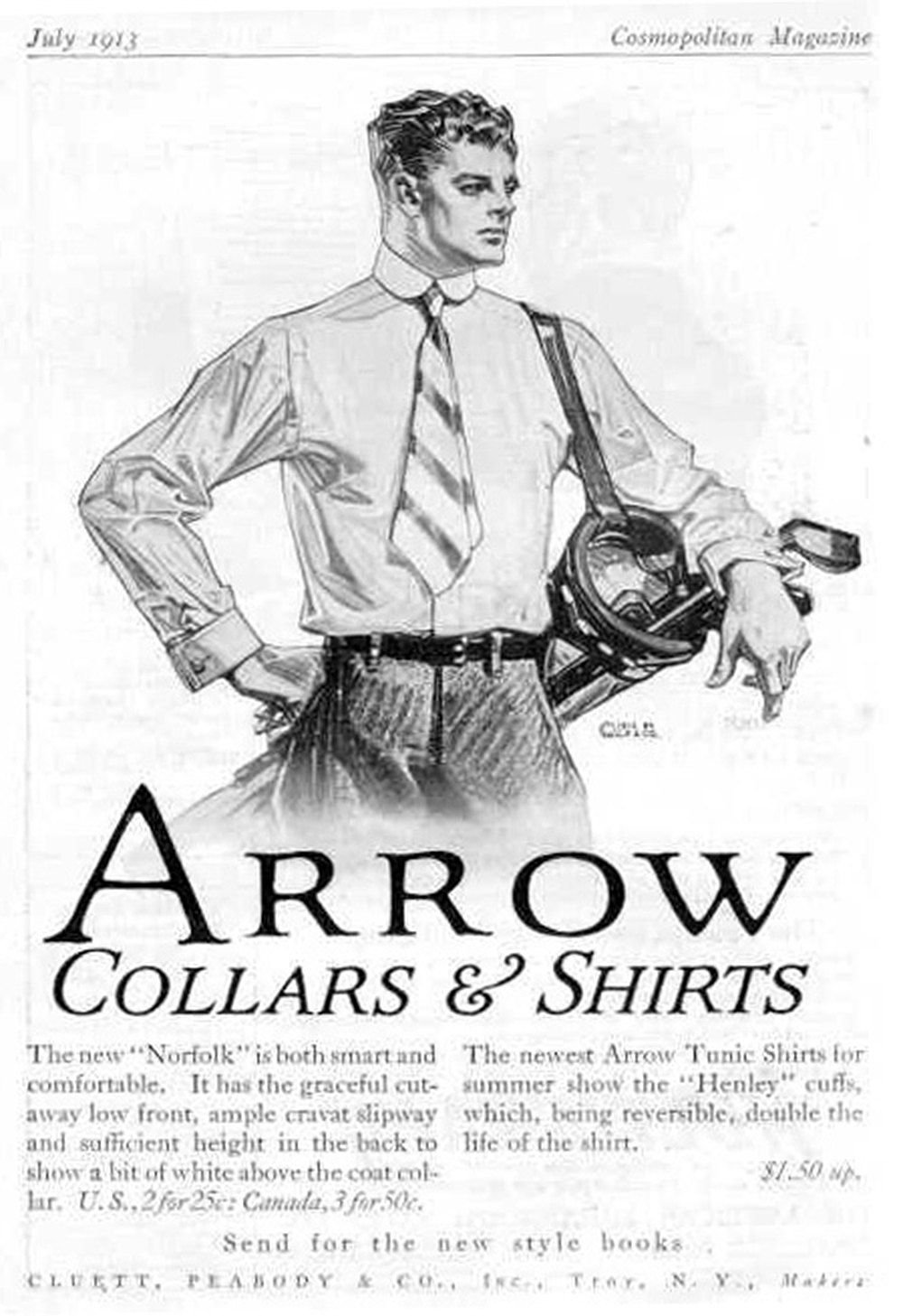

In addition to his Post covers, Leyendecker was well-known for his advertising campaigns for Kellogg’s Cereal, Ivory Soap, Chesterfield Cigarettes, and Procter & Gamble. He created his most famous campaign for shirt and collar manufacturer Cluett, Peabody & Company in 1905. Leyendecker convinced Charles M. Connolly at Cluett to allow him to invent a character who could embody “an ideal American man” and represent the company’s Arrow brand products, creating what is often called the first full advertising campaign. Ads had existed before, but the Arrow Collar Man was the first mascot to embody a brand over a series of advertisements and across many years. The goal was to sell “not just a shirt but the promise of urban sophistication,” according to Norman Rockwell biographer Deborah Solomon.

Over the next few decades, the fictional Arrow Collar Man became an icon, supposedly receiving more fan mail in the 1920s than any male film star of the decade. In an era before the Marlboro Man and Calvin Klein underwear models, the Arrow Collar Man gave Americans an iconography of style and status that would be longed for and lusted after for at least a half century, in which two world wars would come and go but a particular image of masculinity would remain fairly dominant. As Time Magazine once said of the Arrow Collar Man, “All the men wanted to look like him. All the young ladies just plain wanted him.”

Yet though all the ladies wanted him, it was Leyendecker himself who had him. The inspiration for the Arrow Collar Man was Charles Beach, Leyendecker’s main model, muse, and live-in lover. The Cutlers claim that Leyendecker “enjoyed the irony of painting Charles as a prototype, the classic all-American male.” For the time, it would certainly have been subversive and risky to base the country’s most prominent symbol of haughty masculinity on Leyendecker’s own gay lover. Their forbidden love was in everyone’s faces in the ads of one of the country’s most prominent clothing manufacturers and on the covers of America’s favorite conservative magazine, though it remained hidden in plain sight—so much so that few sources even mentioned Leyendecker’s homosexuality until fairly recently. The Arrow Collar Man specifically, and the Leyendecker Man more generally, became the model of style, sophistication, and masculinity. Today the clearest iconographic connection still lingering in the cultural consciousness is likely to be F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

In Fitzgerald’s seminal Jazz Age novel, Daisy Buchanan makes the connection between the Arrow Collar Man and Jay Gatsby herself. She says to Gatsby, “You always look so cool…You resemble the advertisement of the man…You know the advertisement of the man.” While a small number of critics, including Kirk Curnutt, editor of A Historical Guide to F. Scott Fitzgerald, have determined that “the advertising icon Daisy has in mind is likely the Arrow Collar Man, the ultimate 1920s symbol of ‘cool,’ ” scholar Thomas Dilworth is the only one to give an in-depth assessment that attempts to prove this reference definitively in his essay “The Great Gatsby and the Arrow Collar Man.”

Dilworth argues that the connection isn’t just “likely”—we can “be certain that she is referring to the Arrow Collar Man.” He focuses on Daisy’s words, particularly her use of the word the. She doesn’t mention “an advertisement of a man” but “the advertisement of the man.” Therefore, it is implied that those to whom she speaks—not just Gatsby, but Nick Carraway,2 Jordan Baker, and her husband, Tom Buchanan—would know which advertisement she means.

The other interesting thing Dilworth points out is that “almost all advertisements—and this was certainly true in the 1920s—are not, in her words, ‘of the man’ but for the clothes he wears, the car he drives, the Victrola he plays, the radio he listens to, etc.” Daisy assumes that those she’s speaking to not only will know the advertisement but also know the man in the advertisement. Only one ad campaign in the 1920s focused on a character, a personification of chic urbanity, a “kind of man,” as much as his product and had such a level of cultural ubiquity that anyone could mention it indirectly and assume everyone would understand the reference.

The Arrow Collar Man had become a shorthand signifier for a certain look and sensibility. The cultural prevalence of this icon is clear elsewhere in Fitzgerald’s oeuvre. In This Side of Paradise, Fitzgerald writes, “She regarded him gravely, his intent green eyes, his mouth, that to her thirteen-year-old, arrow-collar taste was the quintessence of romance.” Here “arrow-collar” is meant to express an amorous aesthetic so clearly that the reader is expected to glean from the allusion not only the image of the man being lusted after but a sense of the girl doing the lusting as well. But it’s not just “arrow-collar taste” that became 1920s slang for a particular type of attraction to a particular type of man. The name Leyendecker itself entered the lexicon. In a story titled “The Last of the Belles,” Fitzgerald describes “a handsome, earnest face with a Leyendecker forelock.”

In The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald doesn’t complete the reference for us. He doesn’t describe Gatsby as having a “Leyendecker forelock” or Daisy as having “arrow-collar taste,” but the implication is the same. It’s an allusion few modern readers pick up on, but one those at the time were unlikely to have missed.

Some readers thought Gatsby himself was a portrait of Leyendecker. Leyendecker and Beach were regulars at Texas Guinan’s speakeasy in Manhattan, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Mae West, Rudolph Valentino, John Jacob Astor, John Barrymore, Dorothy Parker, Al Jolson, and Fitzgerald himself. Leyendecker and Beach were known to throw extravagant Gatsby-style parties at the mansion they shared with the artist’s sister and brother in New Rochelle. The Cutlers compare Gatsby’s aloofness at his own parties (“standing alone on the marble steps and looking from one group to another with approving eyes”) to Leyendecker’s similar standoffishness: “Like a surgeon selecting a scalpel, Joe too surveyed his guests from the fringes, studying them for future depiction.”

Ernest Hemingway, unlike Fitzgerald, makes no direct reference to Leyendecker in his work. But he was well acquainted with the artist’s Saturday Evening Post covers, his Arrow Collar ads, and the Leyendecker Man in general. Hemingway’s account of Fitzgerald’s looks in A Moveable Feast reads like a description of a Leyendecker painting:

Scott was a man then who looked like a boy with a face between handsome and pretty. He had very fair wavy hair, a high forehead, excited and friendly eyes and a delicate long-lipped Irish mouth that, on a girl, would have been the mouth of a beauty. His chin was well built and he had good ears and a handsome, almost beautiful, unmarked nose. This should not have added up to a pretty face, but that came from the coloring, the very fair hair and the mouth. The mouth worried you until you knew him and then it worried you more.

Of course, the men Hemingway depicts in his novels and stories aren’t usually the dapper society dandies of Fitzgerald’s fiction nor their aesthetic cousins, the fashion-conscious matinee idols of the Arrow Collar advertisements. Nevertheless, they do look like the athletes, soldiers, and outdoorsmen of Leyendecker’s imagination.

Both Fitzgerald and Hemingway, two of the most prominent literary portraitists of masculinity in the first half of the twentieth century, have been accused of misogyny and machismo for transforming Leyendecker’s iconography into words. But the depictions of masculinity in their books are much more nuanced than they may seem at first blush.

“I am half feminine—at least my mind is,” Fitzgerald told his secretary, Laurie Guthrie, in 1935. Nick Carraway, like his creator, is “half feminine” too—a man who finds “something gorgeous” in Gatsby but who is also “full of interior rules that act as brakes on [his] desires.”

Masculinity in all of Fitzgerald’s work is in constant flux: uncertain, inconsistent, but dominated by “interior rules” that come from exterior sources. His characters are men who yearn but learn not to, men more complicated beneath the surface than they appear. As Greg Forter explains in his study Gender, Race, and Mourning in American Modernism, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and many of their modernist contemporaries “came to yearn for a masculinity less rigidly polarized against the feminine.”

Hemingway may be the harder to defend of the two, but his men, even at their most macho, have a sensitivity and an impotence (literal or otherwise) that too often gets overlooked. Wyndham Lewis, a modernist contemporary, perceptively describes Hemingway’s supposedly hypermasculine characters in his book Men Without Art as “futile, clown-like, passive, and above all purposeless.” Though their exteriors might look like beefcake paladins and prize athletes, their interiors are fraught and fragmented. “That is the Hemingway subject-matter to perfection,” Lewis writes, “a man melted in his armor like a shellfish in its shell—melted lobster in its red armor.”

We do Hemingway’s work a disservice to imagine it as the literary equivalent of a wolf whistle or a bar fight; there is a struggle, a wrestling in Hemingway that often gets overlooked in our facile caricature of him. As Mikaella Clements writes, “Hemingway is at once kinder and more lost than we give him credit for.” The Leyendecker Man is also kinder and more lost than we give him credit for. There is hubris there, of course, but Leyendecker also captures a tenderness in these stern brooders, a softness beneath the strong jawlines. These are not images of pure testosterone, but instead images cognizant of the ways “masculinity” as an ideal actually restricts “masculinity” as a unique and individual expression. Even as these men drink socially, hunker down in foxholes, fight bulls, and box one another, they are depicted as much more complex than the world allows them to be. If this is mere rugged manliness, it is “rugged” in a more precise sense: it is broken, uneven, inconsistent.

Leyendecker built into his men a whole spectrum of masculinity, and we can read into them our own longings, our own inadequacies, and our own vanities, too. Where one might initially see toxic men, a deeper look reveals confused and wounded souls, presupposing the crisis masculinity currently finds itself in. It’s not hard to imagine this is because the crisis is neither new nor unique. Through Leyendecker it may be possible to reconsider our understanding of masculinity, to reevaluate the male characters in the work of writers like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, and to see a subversive subtext that has always been there within our iconography of masculinity.

Isn’t it pretty to think so?

If Leyendecker is remembered at all these days, it is for his depictions of metropolitan sophistication. The best remembered images of his protégé, Norman Rockwell, illustrate small-town Americana. One might say that if Leyendecker was the portraitist of East and West Egg, then Rockwell was the painter of Mayberry. But Leyendecker painted provincial Americana as well. His magazine covers depict boys diving into swimming holes, dressing up as cowboys and Indians, playing baseball, and babysitting younger siblings; an undiscerning eye might mistake many of these for a Rockwell.

His holiday covers for the Saturday Evening Post continue to influence the iconography of our major festivities to this day. Leyendecker was one of the first to use the image of a cherubic baby to represent the New Year. Our contemporary image of Santa Claus owes more to Leyendecker’s magazine covers than to Haddon Sundblom’s Coca-Cola advertisements, which too often get the credit but came after Leyendecker’s similar illustrations.3 Rockwell took much of his aesthetic and iconography from Leyendecker, who had almost single-handedly invented the Saturday Evening Post style many now associate with and attribute to Rockwell.

The artist’s presence loomed so large in Rockwell’s life and artistic development that Rockwell dedicates a whole chapter of his memoir, My Adventures as an Illustrator, to his relationship with Leyendecker. For years much of what was “known” about Leyendecker was taken from that memoir.

Rockwell first met “the great Leyendecker” at a banquet, where toastmaster Charles Dana Gibson4 had forgotten to introduce Rockwell to the crowd. The next day the young illustrator lurked outside Leyendecker’s mansion on Mount Tom Road in New Rochelle: “I peeked around the wall and up the driveway to Mr. Leyendecker’s studio windows, gilded by the last rays of the sun, opaque.”

“Should I ask him to dinner?” Rockwell wondered. “He was friendly at the banquet. Yes. But he’s so famous.” As the sun fell behind the line of rooftops, he saw a light flick on and noticed Leyendecker standing all alone. This gave Rockwell the courage to ask him to dinner, but it also let loose some startling admissions in his memoir: “I thought of all the times I’d followed him about town just to see how he acted. And how I’d asked the models what Mr. Leyendecker did when he was painting. Did he stand up or sit down? Did he talk to the model? What kind of brushes did he use? Did he use Winsor & Newton paints?”

Though Rockwell was obsessed with his predecessor, he was not fond of Leyendecker’s companion. According to Rockwell, Charles Beach first came to visit the Leyendeckers because “he had fallen in love with a girl in one of Joe’s drawings and come all the way from Canada to meet her”—a story that seems suspect given Beach’s sexuality but cannot be entirely refuted. In his memoir, Rockwell makes no mention of Leyendecker and Beach becoming lifelong lovers nor any direct comment on Leyendecker’s homosexuality. The closest he gets is a thinly veiled (and arguably homophobic) dig: “There was a lot he’d never known. Women, for instance. Joe could never paint a woman with any sympathy.”5

In Rockwell’s view, Beach “was a real parasite—like some huge, white, cold insect clinging to Joe’s back. And stupid. I don’t think I ever heard him say anything even vaguely intelligent.” Because so little has been written on Leyendecker and even less on Beach, this image of their relationship, conjured by a man who couldn’t remember Beach’s first name, has dominated. There has since been pushback against this cartoonish view. Susan E. Meyer explains in her book America’s Great Illustrators that “reports given by friends and neighbors tend not to be reliable, exaggerating the extremes of each personality involved as though each was a character in a Victorian melodrama: Beach the Villain, Joe the Victim, Frank the Martyred Younger Brother.”

Meyer points out that though Rockwell claims that Leyendecker had been sociable and gregarious before Beach, the few sources there are seem to indicate that “Leyendecker had always been a shy, introverted man.” Rockwell met Leyendecker long after he and Beach had begun their decades-long romance, so he shouldn’t necessarily be trusted as a source of firsthand information on Leyendecker’s pre-Beach life.

There’s no denying that after Beach had a disagreement with Leyendecker’s brother, both Frank and their sister Augusta moved out of the New Rochelle home that they had previously shared with their brother, however. Frank Xavier Leyendecker died a few years later; many speculate that J.C. Leyendecker was racked with guilt and melancholy afterward. By the 1930s Leyendecker and Beach had become increasingly insular with fewer and fewer people in their orbit. According to the Cutlers, “Other than Beach, his sister, and some remote cousins and houseboys, he was said to rarely speak to anyone after 1930—quite different from the convivial host from so many Gatsby-esque parties he had been in the past.” The explanation why Leyendecker went from Gatsby-style party host to shut-in varies from source to source. Rockwell blames Beach—surprise, surprise—though others have opined that Beach was fond of the parties and it was Leyendecker’s sister who put the kibosh on them.

Leyendecker died in the summer of 1951 of heart failure. Within a year, Beach died as well. It’s perhaps too easy to fall into mythic romanticization here and attribute his death to a broken heart, but the couple had been inseparable by that time for almost half a century, living in what Rodger Streitmatter calls “an outlaw marriage.” Leyendecker, who had been unimaginably famous a few decades prior—recognized on the streets of New York, followed around town by the young Rockwell, beloved by Texas Guinan and her star-studded speakeasy clientele—was buried with little fanfare. According to Rockwell, the only people at the funeral of the man who had basically invented the iconography of twentieth-century American masculinity were the priest, the undertaker, his lover Beach, his sister Augusta, the daughter of one of his cousins and her husband, and Rockwell himself.

Rockwell writes in his memoir that Leyendecker, toward the end of his life, said: “I guess if I had to live it all over again, I might have done it differently.” One imagines him sitting in his studio as he said this, looking off into the distance, as alluringly unattached as one of his own creations, a Leyendecker Man. He then added: “But maybe I couldn’t have...”

1 For example, Schau writes, “Joseph was the firstborn son; his brother Frank Xavier was born three years later. A sister, Augusta, the third and last child, arrived after the family had emigrated to America.” The Cutlers’ book proves that Joseph was not the firstborn son: there was a fourth child, Adolph, born in 1869, five years before Joseph. Also, Joseph’s sister, Augusta, was not born after the family had emigrated to America; she couldn’t have been, for she was born before Joseph, in 1872. So Joseph was actually the third-born child and second-born son. ↩

2 Nick Carraway makes his own connection between Gatsby and magazine advertisements when he says that listening to Gatsby is “like skimming hastily through a dozen magazines.” ↩

3 Leyendecker was not without his antecedents—most notably Thomas Nast and Reginald Birch—but our modern-day image of Santa Claus arguably owes as much to Leyendecker as anyone else. His holiday Saturday Evening Post covers helped popularize the image that Sundblom would later solidify in his Coca-Cola advertisements: the jolly, plump, rosy-cheeked old man with a long white beard and a sack full of toys decked out in a red suit trimmed with white fur. ↩

4 Gibson is famous for giving us an iconography of twentieth-century femininity with his now-iconic “Gibson Girl,” who could be considered the counterpart to (and half the gendered pair with) the Leyendecker Man. Leyendecker supposedly shared this view of his own work. His women are by no means unattractive or underdeveloped as characters—they are impeccably well rendered—but the men, almost to a man, drip with a desirousness not present in his portrayals of women. This is the male gaze setting its sights on the male. ↩