History does not reach us only in classrooms and via textbooks; movies, novels, songs, and even video games have shaped how we understand what came before the present for generations. Lapham’s Quarterly is exploring the history and allure of pop culture’s period pieces, artifacts that captivated audiences with their conceptions of the past—and the political and cultural contexts that made these historical fictions so compelling.

On September 5, 1987, under the spell of the sinking and watery city where Aschenbach first saw Tadzio emerge from the sea like some frail and golden god in Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, the Merchant-Ivory adaptation of E.M. Forster’s cross-class gay romance Maurice premiered at the Venice Film Festival. The production was chummily Anglo-American, making for a curiously polite protest (if protest it was) against the colonial nostalgia and reactionary homophobia of the Reagan-Thatcher years. As much an uncritically aestheticized portrayal of elite English Edwardianism as it was a melancholy glamorization of closeted gay life, the transatlantic confection cost £1.58 million, a sum that would have bought 262 AIDS patients a year’s worth of Retrovir (AZT), licensed for use that year at a price that made it the world’s most expensive drug to date. What are the politics of visual pleasure for a movie about nascent queer love filmed in the time of AIDS but set in the late imperial cocoon of clipped lawns and subfusc?

Forster began writing Maurice in 1913, when the British Empire governed nearly a quarter of the earth’s population and the question of nostalgia was beside the point. Forster was thirty-four, eighteen years had passed since Oscar Wilde’s conviction for “gross indecency,” and it would be another fifty-four years before “homosexual acts” were decriminalized in the United Kingdom. Completed in 1914 and subsequently revised several times, Maurice was published only after Forster’s death in 1970, a year after Stonewall; understandably fearing homophobic reprisal, he had refused to publish the novel in his lifetime, instead leaving the manuscript to his friend Christopher Isherwood, who subsequently oversaw its publication in 1971. The barely canonical novel circles around the story of Clive Durham and Maurice Hall, Cambridge undergraduates who fall in love reading Plato’s Symposium and listening to Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique Symphony. In a “Terminal Note” appended in 1960, Forster reveals that Maurice “was the direct result of a visit to Edward Carpenter,” the Cambridge-educated, sandal-wearing gardener, poet, and utopian socialist who lived with his much younger, rather more working-class boyfriend, George Merrill, in Millthorpe, a village in Derbyshire. Forster praises the intellectual example of Carpenter but credits Merrill’s ambient sensuality with instigating the novel:

George Merrill also touched my backside—gently and just above the buttocks. I believe he touched most people’s. The sensation was unusual and I still remember it, as I remember the position of a long-vanished tooth…I then returned to Harrogate, where my mother was taking a cure, and immediately began to write Maurice. No other of my books has started off this way.

The excessive repression evinced by this explanation of Maurice’s origins would be comical if its cause—the criminalization of gay life—had not been so cruel. A similarly breathless, faintly dusty atmosphere of sophomoric fumbling pervades the novel itself, at times sickeningly.

Rejecting Victorian portrayals of homosexuality as tragic and ruinous, Forster insisted that “a happy ending was imperative,” but most of the story is still pretty gloomy. When Maurice initially condemns Clive for his profession of love, the narration (couched in free indirect discourse) sounds straight out of the literature of homosexual doom Forster explicitly sought to avoid:

Great was the pain, great the mortification, but worse followed. So deeply had Clive become one with the beloved that he began to loathe himself. His whole philosophy of life broke down, and the sense of sin was reborn in its ruins, and crawled along corridors. Hall had said he was a criminal, and must know. He was damned.

Even at the high point of the affair, when Maurice and Clive keep close but rather chaste company for a time in London together, the novel gives us only a very muted sense of mutual satisfaction: “During the next two years Maurice and Clive had as much happiness as men under that star can expect.” By the end of part 2, Clive and Maurice break as lovers when Clive, the more posh of the two and anxious to protect his class privilege, decides to marry a woman. They brawl on the floor, with Maurice weeping and saying, “What an ending, what an ending.”

It was not, of course, the novel’s ending, since Maurice goes on to fall in love with Alec Scudder, a young servant on the Durham estate. The unhappily married Clive greets the revelation of Maurice’s new entanglement with genteel contempt, barely comprehending what he has been told: “Intimacy with any social inferior was unthinkable to him.” But Forster did not celebrate the transcendence of social hierarchy he had so vividly witnessed in the Carpenter-Merrill household. A few chapters earlier, Maurice is disgusted to learn that his new lover was a son of the village butcher: “Maurice flung his hat on the floor of the car with all his force. ‘That is about the limit,’ he thought, and buried both hands in his hair.” So much for love that knows no bounds; though estranged, Clive and Maurice speak as class equals behind the back of Maurice’s new love, the butcher’s son. Though Clive, with his country estate and London house, clearly outranks Maurice, a mere stockbroker, their shared time at Cambridge sealed them together in a gentleman’s pact of noble sexlessness—highly dramatic, gloriously narrated, and later lushly filmed. Hypnotized by the sullen passion of the Clive-Maurice romance, we learn almost nothing about the ostensibly triumphant love of Maurice and Alec, which suddenly (and without any convincing characterization on either side) escapes the overwhelming constraints of class and sexual repression, ending the novel in an inchoate glimmer, a conditional possibility, an afterthought.

There is a certain line of argument that would dismiss these skeptical reflections as hopelessly anachronistic, insisting that Foster was a lion in his own time, visionary in his imagining of still-unthought queer love. But the reactions of Forster’s friends and contemporaries, several of whom read drafts of the book, would suggest otherwise. Carpenter was lukewarm in his praise, telling Forster in an August 1914 letter that he didn’t “always like your rather hesitating tantalizing impressionist style.” He did appreciate that the ending is a happy one: “I am so glad you end up on a major chord.” Bloomsbury critic Lytton Strachey was more frank about the limits of the evasiveness that Carpenter called “tantalizing,” excoriating Forster for sexless scenes that appeared so primly anti-erotic compared to Strachey’s own exuberant homosexuality: “I really think the whole conception of male copulation in the book rather diseased—in fact morbid and unnatural.” Perhaps the harshest reaction came from Hugh Meredith, a married former classmate to whom Forster had dedicated A Room with a View: he was so indifferent to the manuscript that Forster felt their very friendship had been called into question. Even Forster was less than sanguine about the novel’s prospects, writing to his friend Florence Barger in 1915, “To you [Maurice] will reveal a new and painful world, into which you will hardly have occasion to glance again.” Major chords aside, to Forster the world of homosexuality was a painful one—how could it be anything but in 1915?

While Forster’s contemporaries saw Maurice as behind even their own times, the generation that followed him would come to see the novel as a precursor to gay liberation. Looking for a pair of fresh eyes for his old draft in 1932, Forster turned to the young Isherwood, only twenty-eight and already the author of two novels as well as a constant companion of W.H. Auden’s in the erotic, artistic, and intellectual playgrounds of interwar Berlin. In his 1976 autobiography Christopher and His Kind—itself a kind of coming out from the more winking, novelistic recounting of the same period in 1939’s Goodbye to Berlin—Isherwood evokes the scene of their first meeting in a deflective third person:

Christopher sits gazing at this master of their art, this great prophet of their tribe, who declares that there can be real love, love without limit or excuse, between two men. Here he is, humble in his greatness, unsure of his own genius. Christopher stammers some words of praise and devotion, his eyes brimming with tears. And Forster—amused and touched, but more touched than amused—leans forward and kisses him on the cheek.

Paradoxically, a novel that seemed too stilted, “impressionistic,” “morbid” even to Forster’s contemporaries becomes a moving celebration of male love “without limit or excuse” to a leading writer of the ostensibly more liberated 1930s generation. Isherwood sees the older novelist’s hesitation as humility and the mildness of his experiment as prophetic of a still more permissive world to come. In contrast with Forster’s more critical Edwardian contemporaries, who saw him as something of a sexless fuddy-duddy, Isherwood blames the Edwardian period itself for Maurice’s chasteness, elegizing Forster as a “wonder” who, “imprisoned within the jungle of prewar prejudice,” could nevertheless put “those unthinkable thoughts into words.”

A decade later, Isherwood was dead and gay liberation was about to suffer its harshest test. Ronald Reagan was sworn into a second term in 1985 and Margaret Thatcher into a third in 1987. By the end of 1987, three months after Maurice screened at Venice, more than forty thousand had died of AIDS in the U.S. The number of reported cases had topped fifty thousand. On Reagan’s orders, noncitizens with HIV were barred from entering the country. The same year Larry Kramer founded ACT UP. Clearly, an opulent fantasy of gay Edwardian infatuation wasn’t in the zeitgeist. Or was it?

For those who had seen other film adaptations by the producing and life partners James Ivory and Ismail Merchant, Maurice’s ambiance was to be expected. Directed by Ivory (who cowrote the screenplay with Kit Hesketh-Harvey) and starring Hugh Grant as Clive, James Wilby as Maurice, and Rupert Graves as Alec, the Merchant-Ivory Maurice leans heavily, and predictably, into the atmospheric glitz of the antique, the precious, the privileged. True to Forster’s ambivalent eros, bodies are kept to a polite minimum, impeccably styled. Indeed, style itself becomes an object of attraction, and one is almost unsure whether to fall in love with the undeniably beautiful trio of lead actors or the surrounding furniture and houses.

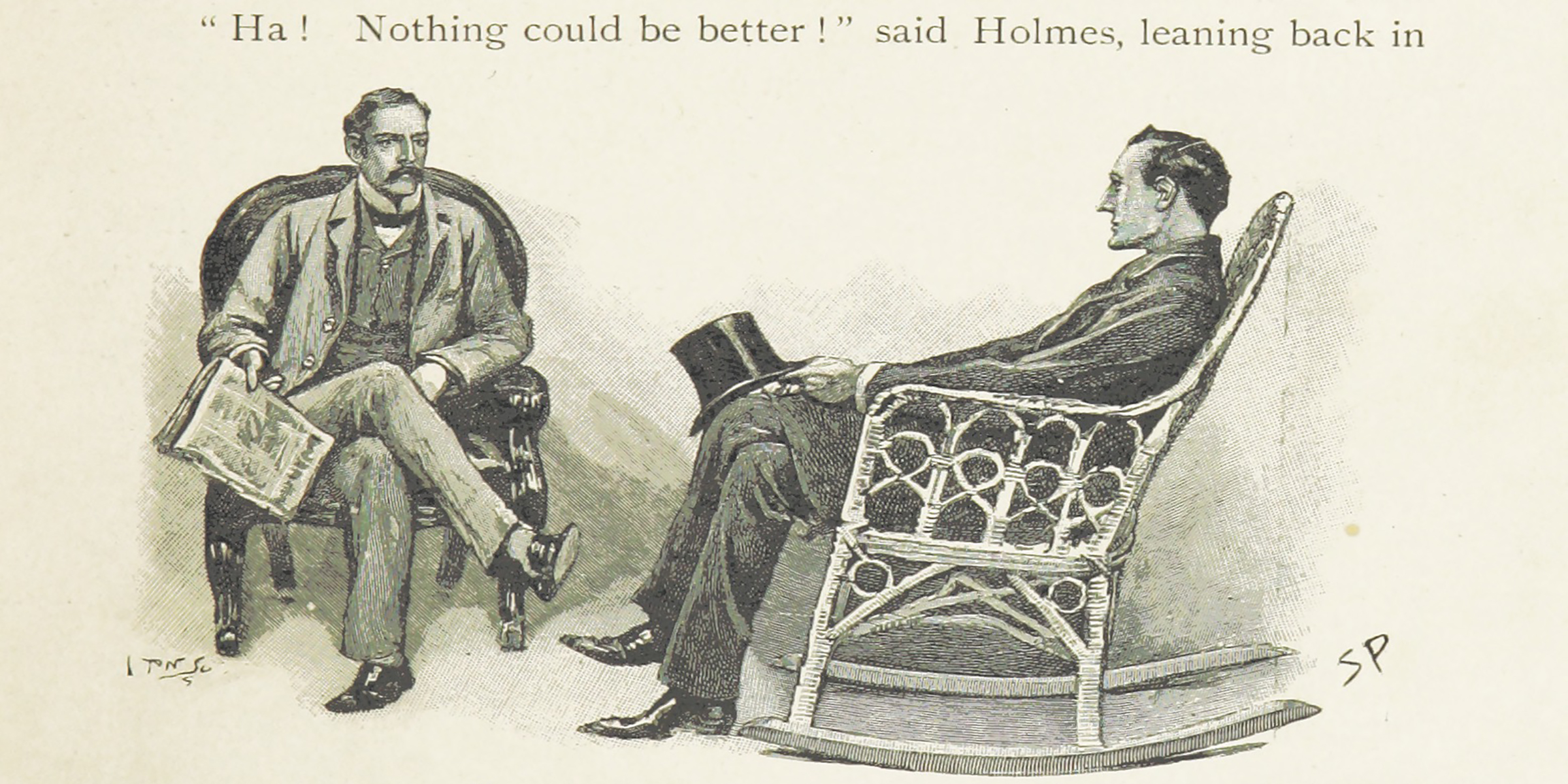

Apparently Ivory wasn’t sure either. At one of the summits of the film’s over-exquisite longing, Grant rests his handsome head ever so suggestively on Wilby’s khaki knee to the plaintive strains of “Miserere mei,” Allegri’s 1638 setting of Psalm 50. Suddenly the music stops. A nape is stroked, locks twirl, and, as the protagonists shift, turning for a kiss, the creak of wicker is heard. An awkward noise for a collegiate kiss? Not so, thought the film’s director, who told The New Yorker in 2017, “The sound of that wicker chair is so sexy…it’s a fantastic sound. It just happened.” While probably not what ACT UP had in mind when its members chanted, “We’ll never be silent again! ACT UP!” in reference to its 1987 poster campaign “Silence=Death,” the creak of wicker and rustle of silk do capture the discreet aesthetic of the film’s version of gay life. Critics of Ivory’s too sunny, almost rose-colored view of the English high bourgeoisie (no one is quite an aristocrat) may be surprised to learn that this cold palette extended even to the cinematography, and quite deliberately. In his recently released memoir, Solid Ivory, Ivory recalls, “In later life I turned to chillier colors myself, and told my cameramen and art directors that I wanted certain films of mine to be predominantly cool in color, as for instance Maurice.” Thus the several paradoxes of Maurice compound: a deeply sad book built around a happy ending turned into an almost baroquely passionate film shot in self-consciously cool colors.

Though profoundly repressed, the Merchant-Ivory Maurice is in fact—and perhaps despite itself—a weirdly emotional movie, arguably outstripping the novel itself in this respect. The film’s principal characters are frequently seen weeping, passing out, breaking down. Shortly after his Cambridge friend Lord Risley is convicted and imprisoned for gross indecency, Clive has a fainting spell at the Hall family dinner table, collapsing to the floor in a crash of china, and has to be carried upstairs and put to bed by Maurice. When Maurice calls for a doctor, the man insists that the Halls call for a nurse. In the scene where Clive and Maurice have their parting as lovers, Wilby says the line “What an ending, what an ending” with tears streaming down his face, trembling, shaking, convulsing almost, falling back into a chair and curled into himself like a shattered and helpless infant. To Forster’s original dialogue, Ivory and Hesketh-Harvey add “What’s going to happen to me?” and “I’m done for.”

An aura of unraveling, anxious panic and indistinct, undiagnosable illness pervades the second half of the film, with Maurice seeking out first his family doctor and then a specialist in hypnotism, increasingly hysterical. Declaring himself an “unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort” to Dr. Barry (Denholm Elliott), Maurice asks, again teary-eyed, his voice quavering, “Am I diseased? If I am, I want to be cured.” Supine on the couch of the hypnotist Lasker Jones (Ben Kingsley), Maurice cries bitterly at the suggestion he envision a pretty girl, saying, “I want to go home to my mother,” and barely stammering out, “She’s not attractive to me” and “I like short hair best” through profuse tears. Ivory may have intended his response to the death and decay of the body that so grimly defined the AIDS era to be one of slick hair and perfect skin, white-tie attire, and, of course, wicker. But even in this nostalgic, romantic idyll of abstinent love and apparently inviolable privilege, queer love is never far from the three-headed Cerberus of medicine, law, and pseudopsychology. Sickness always finds its way in, hissing, “Et in Arcadia ego” in a crystalline whisper.

Maurice was released in the United States on September 18, 1987, thirteen days after its premiere in Venice and almost exactly five weeks after I was born. When I was a teenager, the film acted as a kind of code word for bookish, pre-Grindr gays: “Have you seen Maurice?” It’s since become something else, an escape, perhaps, from a new sickness, a new death. I watched Maurice most recently with my boyfriend in the third week of March 2020, hiding in dread and reading CDC press releases as a new pandemic shut down New York. Soon enough there were rumors that patients with HIV wouldn’t be given ventilators. I was thirty-three, he was twenty-three, and in all the years since we’d joined the unspeakables of the Oscar Wilde sort, not a day went by that we didn’t remember the pandemic of forty years and forty million, the one whose name was hard to speak even now, the one that cost a generation. Somewhere between Central Park’s Great Lawn under pastel skies and the bright terror of boyish love on England’s green and pleasant land, we walked alone and waited for what would come, watching as Maurice Hall sought doctors for a disease for which there was no cure and barely a name. For me this was the heart of what it meant to watch the film in our acutely vulnerable moment: so much promise, so much beauty, but never quite fulfilled. Because we were in love, we thought of love; because it was queer love and so many had died and so many more would die still, we thought of death. If Maurice was a tragedy in its own time, and a witnessing and memorial in ours, it was for this reason: that so much love had given rise not to life but to loss. That even the strongest bond could not protect us. That there would be few happy endings. That we might not last the night.

Read past entries in this series: Caroline Wazer on Assassin’s Creed, Kristen Martin on orphan trains, Jeremy Swist on heavy metal’s fascination with Roman emperors, and Emma Garman on the Happy Valley set.