On Stage II, by Edgar Degas, 1876. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Katherine E. Bullard Fund in memory of Francis Bullard, by exchange.

A common legend in the theater holds that by 1599 William Shakespeare had grown tired with the clowning antics of the actor William Kempe. As a member of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, Kempe played Launcelot Gobbo in The Merchant of Venice, Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing, and Peter in Romeo and Juliet. His greatest character was a “goodly portly man…of a cheerful look, a pleasing eye, and a most noble carriage” named Falstaff. Prince Hal’s compatriot and drinking buddy is a comedic role of the utmost sophistication, a cowardly knave capable of deep irony and introspective cynicism, who Harold Bloom claimed was the “grandest personality in all of Shakespeare.” Yet Falstaff’s creator felt that Kempe’s style was old-fashioned and derivative, drawing from the doggerel punning of the clown Richard Tarlton, whose pranks had audiences laughing only a generation before. Now such antics seemed stale. The playwright and poet Thomas Nashe agreed, noting that Kempe was mostly a “jest-monger and vice-gerent general to the Ghost of Dick Tarlton.”

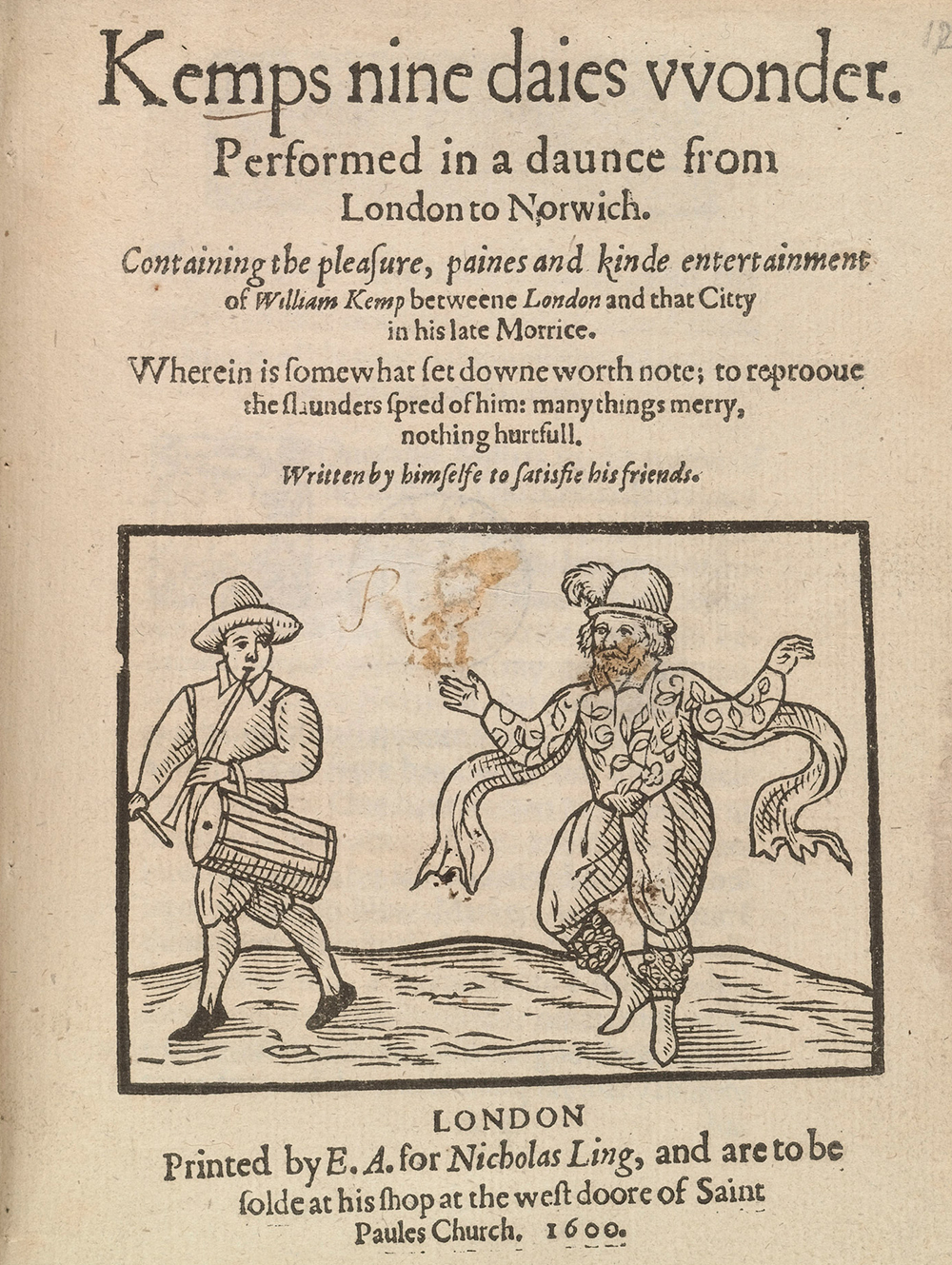

Shakespeare replaced his clown with the more nuanced comedic actor Robert Armin, who was poached from a troupe supported by William Brydges, Baron Chandos. After his departure, Kempe found new ways of entertaining audiences, such as when he supposedly performed a lively Morris dance the hundred miles between London and Norwich in mottled pants and belled caps. (He meant to complete the marathon publicity stunt—which he wrote about in a 1600 pamphlet—in nine days, but it took twenty-three, after frequent stops and at least one strained hip and a tumble into a ditch.) By contrast, Armin had developed a reputation as a quick wit, brilliant at improvisation and adept at subduing an unruly audience with cutting barbs. Scholar Stanley Wells explains in Shakespeare & Co. that “after Armin’s recruitment Shakespeare began to create clowns who are more wistful, introverted, and musical: semi-choric commentators on the action.” These included Touchstone in As You Like It, Feste in Twelfth Night, and Lavatch in All’s Well That Ends Well. The disturbing, nihilistic clown who accompanies King Lear on the element-blasted hearth—“I am better than thou art now; I am a fool, thou art nothing”—was a role supposedly written with Armin’s particular genius in mind, as was Iago from Othello (though there is far from a scholarly consensus on the casting). Critic Frank Kermode speculates in The Age of Shakespeare “that if Armin had not joined the company these roles might not exist in the forms familiar to us.”

So iconic are these characters, so familiar, and so oft rendered that it’s hard to imagine the actors who originally performed them. More than three centuries before Orson Welles gave us his Falstaff, that character was endowed with life by Will Kempe; long before Bob Hoskins, Ian McKellen, or Kenneth Branagh could slither next to Othello’s ear, Robert Armin had defined Iago. While we can’t know which actors played which parts across the entirety of Shakespeare’s oeuvre, there is a tremendous amount we do know, in part because the quartos of his plays (cheaply printed copies of individual scripts) name the players. The reputation of some actors was equal to that of the playwrights (with significant overlap), so that even though it’s impossible to visualize exactly how they performed—the timbre of a voice, the expression on a face, the placement of a body—we often understand a surprising amount about their work. Theater is a collaborative art, and as much as the English stage of the era offered something revolutionary in presenting original secular drama, that innovation was due not just to those who penned the plays but also to those who performed them.

Secular theater as we would broadly recognize it was an Elizabethan innovation. During the Middle Ages, drama was reserved for the elaborate religious cycles performed by amateur actors, frequently drawn from professional guilds that represented the trades, such as carpenters or bakers, who staged performances tied to the liturgical calendar. Throughout the sixteenth century the purpose of the theater began to change, as the vogue for humanism encouraged the staging and writing of plays with classical and historical themes. Even before the opening of the first designated theater for new plays, the short-lived Red Lion in 1567, secular scripts had been performed in aristocratic manor homes, grammar schools, and the Inns of Court. The simply named Theatre, one of the most popular stages of the era, was constructed in 1576 by James Burbage, scion of a well-known acting family and father of Shakespeare’s favored performer Richard Burbage. At this point everything in the burgeoning entertainment industry accelerated, and new venues—the Curtain Theatre in 1577, the Rose in 1587, the Swan in 1595, the Fortune in 1600—rushed to keep up with the creative output of playwrights and the demands of audiences. Shakespeare’s Globe joined them in 1599.

With theaters largely consigned to first Shoreditch, just north of the City of London, and later Southwark directly south of the City, a vibrant and insular professional community developed. The industry didn’t just employ actors and playwrights. A fleet of watermen, for example, ferried audiences across the river, and concession operators sold roasted hazelnuts and oranges to those in attendance. In such a thriving community, albeit one that was comparatively small, various troupes of actors and playwrights engaged in competition both good-natured and not. The poaching of players like Armin wasn’t uncommon, and authors would often directly mock and slander one another on the stage. During the war of the theatres from 1599 to 1602, Ben Jonson and his adversary Thomas Dekker maligned each other across half a dozen plays, with Shakespeare jokingly referring to the possibly concocted rivalry between the pair in Hamlet when the character Guildenstern observes that “there has been much throwing about of brains.” For the first actors, performance wasn’t just business, it was an entire lifestyle, and for men like Jonson, Dekker, and Shakespeare, the play was perhaps less the thing than the stage itself was.

In considering Shakespeare’s first folio, thirty-six plays printed in 1623, seven years after his death, and edited by actors John Heminges and Henry Condell, it can be easy for literary scholars such as myself to slide into thinking about these works as somehow existing beyond the grubby world of the actual theater. And yet as literary scholar Andrew Gurr reminds us in Playgoing in Shakespeare’s London, Shakespeare wrote “for a highly specific stage…not for any theater in the abstract nor for the printed page.” This was true of not just Shakespeare but also Jonson, Christopher Marlowe, and their contemporaries. Shakespeare didn’t have in mind an arid graduate seminar, but rather wrote for the Globe Theatre in the warm dwindling sunlight—the length of acts had to be timed to end before it became too dark. The background noise of theatergoers loudly munching on concessions would require consideration as well. Scenes would need to be scheduled so that Blackfriars’ stagehands could cut candlewicks, lest smoke sting the eyes of performers. So prevalent is the contention that Shakespeare was “not of an age, but for all time,” as Jonson wrote, that we can forget how he was very much of his own age, one that he shared with the actors who performed his words.

Metaphors about performance recur throughout the folio: “All the world’s a stage,” from As You Like It; “Our revels now are ended. These our actors / As I foretold you, were all spirits,” from The Tempest; and life is called “a poor player / That struts and frets his hour upon the stage” from Macbeth. In that last soliloquy the Scottish king describes all of us as being walking shadows, an apt summation of the actor’s art as well. Only so far back can we as modern people directly approach the actor’s art. The earliest Lear available on film is Ermete Novelli’s silent performance in a 1910 Italian adaptation; the oldest Macbeth we have is the French actor Paul Mounet’s version from 1909—a previous American movie was produced but has been lost to history. The first Hamlet to survive features Sarah Bernhardt in a two-minute silent film from 1900, itself a satisfying inversion of the Renaissance stage’s gender conventions. The invention of recording technology was revolutionary because it solidified the previously evanescent nature of performance, but the nature of performance before that event horizon remains inaccessible. Unlike a fixed text, whose words we can appreciate centuries later, none of us will ever see Kempe’s clowning or the work of all those who followed him. And then there are all those who performed Shakespeare’s great female roles—Lady Macbeth and Ophelia, Cleopatra and Portia, Juliet and Emilia. The prepubescent boys who played those roles (sometimes conscripted against their own wishes) also helped create their characters, but their names are mostly forgotten.

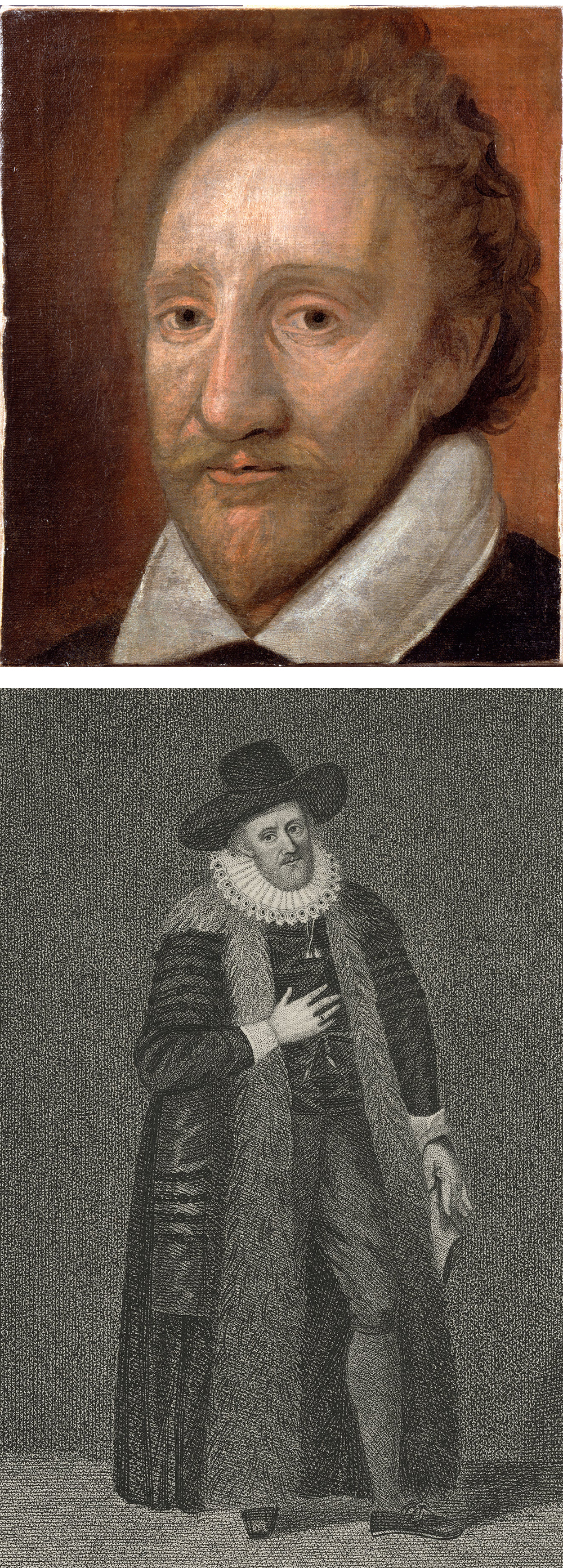

Anxiety over these lacunae has helped generate a sentiment described by the critic Ron Rosenbaum, who recalls in The Shakespeare Wars reading a “somewhat obsessive scholarly paper” that posited an “unbroken chain of Hamlets.” In this hypothesis, an actress like Bernhardt perhaps saw the great nineteenth-century Victorian actor William Charles Macready play Hamlet, and he in turn may have seen John Philip Kemble’s Shakespearean performances—all the way back to Richard Burbage, the first actor to play the role. Like a game of actorly telephone over four centuries, a certain intonation of pitch, or a way of holding one’s body, might be delivered as an inheritance from Shakespeare’s day. It’s a romantic conjecture, as theaters were closed for the two decades of the Puritan Interregnum in the middle of the seventeenth century. It’s unlikely that any of the Shakespearean actors who performed once the Restoration reopened the stages had any clear personal memory of Burbage’s performance. And yet it’s hard not to feel a bit of the actor’s personality conveyed in the anonymous contemporary oil painting of Burbage held by the Dulwich Gallery in London. With warm eyes and a slight smile, the portrait gives a sense of how the actor might appear on stage, the sheer presence of the man an unexpected revelation for those who imagine Hamlet as slight, slender, and sensitive.

Like all Renaissance companies of actors—the Queen Elizabeth’s Men, Lord Strange’s Men, the Earl of Pembroke’s Men—Shakespeare’s company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later the King’s Men), was affiliated with an aristocrat who gave the otherwise disreputable profession the stamp of legitimacy. All of these companies worked grueling schedules on behalf of their patrons. The Admiral’s Men, for example, performed for forty-nine straight weeks during the 1594–95 season, taking off only the Sabbath and going on hiatus only during Lent. During that time the troupe staged thirty-eight different plays, twenty-one of which were new. Memorization of lines was facilitated with “cue scripts”: an actor would know only their own part and the lines spoken directly before theirs. This was done not only to ease memorization but also to prevent the theft of scripts, which could then be sold to printers. The scripts for plays had to be completed in anywhere from four to six weeks, often by the hand of multiple writers who had stage experience themselves (as Shakespeare did, playing the ghost of Hamlet’s father and other roles). Wells explains that Shakespeare’s plays are “imbued with knowledge and understanding of the profession,” with a practical approach to “how many actors are available, how long it will take for them to change from one costume to another and get from the lower to the upper stage…and how much doubling he can impose.”

An author also had to take into account the temperaments, talents, and deficiencies of individual actors when writing a character. When we imagine Hamlet we might have in mind Laurence Olivier, Ethan Hawke, or David Tennant, but Shakespeare was thinking of Burbage, who also originated the roles of Richard III, Othello, and Lear. Among audiences and playwrights alike, Burbage was celebrated for his naturalism; the poet Thomas May enthused that he presented “grief in such a lively color,” and the dramatist John Webster simply called him “an excellent actor.” He was often contrasted with Marlowe’s favored performer Edward Alleyn, an actor with the Admiral’s Men. As the critic Richard Baker would write a half century after Alleyn and Burbage’s heyday, they were “two such actors that no age must look to see the like.” Where Burbage was subtle, Alleyn was loud; where the former worked within studied silence, the latter positively bellowed. Jonson criticized Alleyn’s strutting style as “furious vociferation.” Burbage himself (or Shakespeare) mocked it in Hamlet, condemning actors who “tear a passion to tatters, to very rags, to split the ears of the groundlings.” But Alleyn also had his advocates. The playwright Thomas Heywood praised him as the “best of the actors,” and even Jonson wrote in a poem that he “did give / so many poets life, by one should live.” Alleyn’s volume was suited to raging, with Marlowe designing for him the titular conqueror in Tamburlaine the Great, Barabas in The Jew of Malta, and Doctor Faustus.

At the height of their careers, men like Burbage and Alleyn, Kemp and Armin, were more celebrated than the playwrights who crafted their lines. Social historians have long emphasized how the division between high and low culture hadn’t ossified quite so completely yet. Although it’s anachronistic to compare the Renaissance stage to present-day examples of popular culture, it’s easy to see intimations of our own entertainments in the fandom directed at these celebrities. Kempe, for example, might have been seen as the less subtle comedian when compared to Armin, and yet accounts describe how the mere appearance of the jester on stage, smiling and wagging an eyebrow, resulted in paroxysms of laughter from the audience, who expected such gestures from the famous actor as if he were a beloved character in a contemporary sitcom pratfalling into his neighbor’s apartment. Or consider the esteem in which theatergoers held Alleyn, with the contemporary historian Thomas Fuller opining that his skill was such that “he made any part to become him”—a declaration reminiscent of how modern-day critics describe Method actors. It’s humbling to consider just how much of Shakespeare, or Marlowe, or any other playwright from the period crafted their work with these performers in mind, and just how much of the enchantments of the stage were a negotiation between actor and audience. The author’s name might not even be mentioned.

Perhaps these lost companies live on as more than shadows, the faint chorus of their voices audible in the plays themselves. None of us will ever hear Alleyn’s bellowing or see Kempe’s clowning, but traces of their talents must figure into the text of the plays, though it’s impossible to always tell how. An actor will approach a script differently than the person who wrote it, and in performance there are fortuitous accidents that lend themselves to revision. Alterations by actors through rehearsal and trial and error could explain some of the differences between the quartos of Shakespeare’s plays, which were printed and sold while he was alive, and the folio published several years after his death and traditionally accorded the role of being authoritative. Rosenbaum explains how the 1603 quarto of Hamlet has been “dubbed ‘Bad’ because it appears to be a truncated and garbled version of the play—a sort of seventeenth-century bootleg edition.” In that early printing the most memorable line of Hamlet is rendered as “To be or not to be; ay, there’s the point.” In our own century, when audiences, students, and readers encounter that original rendering, it can seem awkward in its colloquialism, almost funny when compared to the iconic grandiosity of the canonical version. Did theatergoers in Shakespeare’s time have a similar reaction? Did somebody laugh when Burbage had hoped they would sigh? Was the rewrite of Hamlet’s famed monologue Shakespeare’s choice? Or is an improvisation of Burbage whispering down through performance after performance?