Going to Church, by William H. Johnson, c. 1940. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Harmon Foundation.

When the freeman James Easton bought a pew in the white section of the Baptist church in Stoughton, Massachusetts, around 1815, church elders asked him not to sit in it. They cited First Corinthians as evidence: “All flesh is not the same flesh: but there is one kind of flesh of men, another flesh of beasts, another of fishes, and another of birds.” The elders argued that there were further gradations of flesh within the category of men left unexplored in the Bible, visible among people in the form of complexion—hence the need to separate those white congregants from the dark-complected ones. Easton refuted this reasoning by making reference to the same chapter of Corinthians: “There is one kind of flesh in men.” The elders relented but asked him to defer to the “peace and harmony” of the church by relinquishing his pew. As his oldest son, Joshua, told the white abolitionist Lydia Maria Child for her 1834 volume The Oasis, the Eastons still came that first Sunday to sit in their pew.

When the family arrived the second Sunday, they found that the other congregants had tarred it. The next week they narrowly missed tripping the cord to a bucket of water suspended above the pew. When the Eastons kept coming, the congregants ripped the pew out of the floorboards. Undeterred, the Eastons lugged their own bench into the empty place where the pew had been. So the congregants tore out the floor.

In November 1828 James Easton’s youngest son, Hosea, now thirty and a minister himself, delivered a speech to the free persons of color of Providence, Rhode Island, condemning Northern racism and bemoaning the terrors and humiliations like those suffered by his family in Stoughton. Black worshippers were still made to sit in “the most remote part of the house of God,” that part of the church “too demeaning to have beasts as its occupants,” he said. Barriers to education and professional life were plunging the nominally free of the North into poverty and dissipation, and the “colonizing craft”—that “diabolical pursuit, which a great part of our Christian community are engaged in”—was endeavoring to rob free men and women of their rightful claim to American soil. Easton urged his listeners to fight these degradations with moral probity and community solidarity. “When our operations become united and the voice of our community may be heard as the voice of one man,” he said, then free black Americans will be able to “control the effects of our own labor, and make it subservient to the benefit of our own community.”

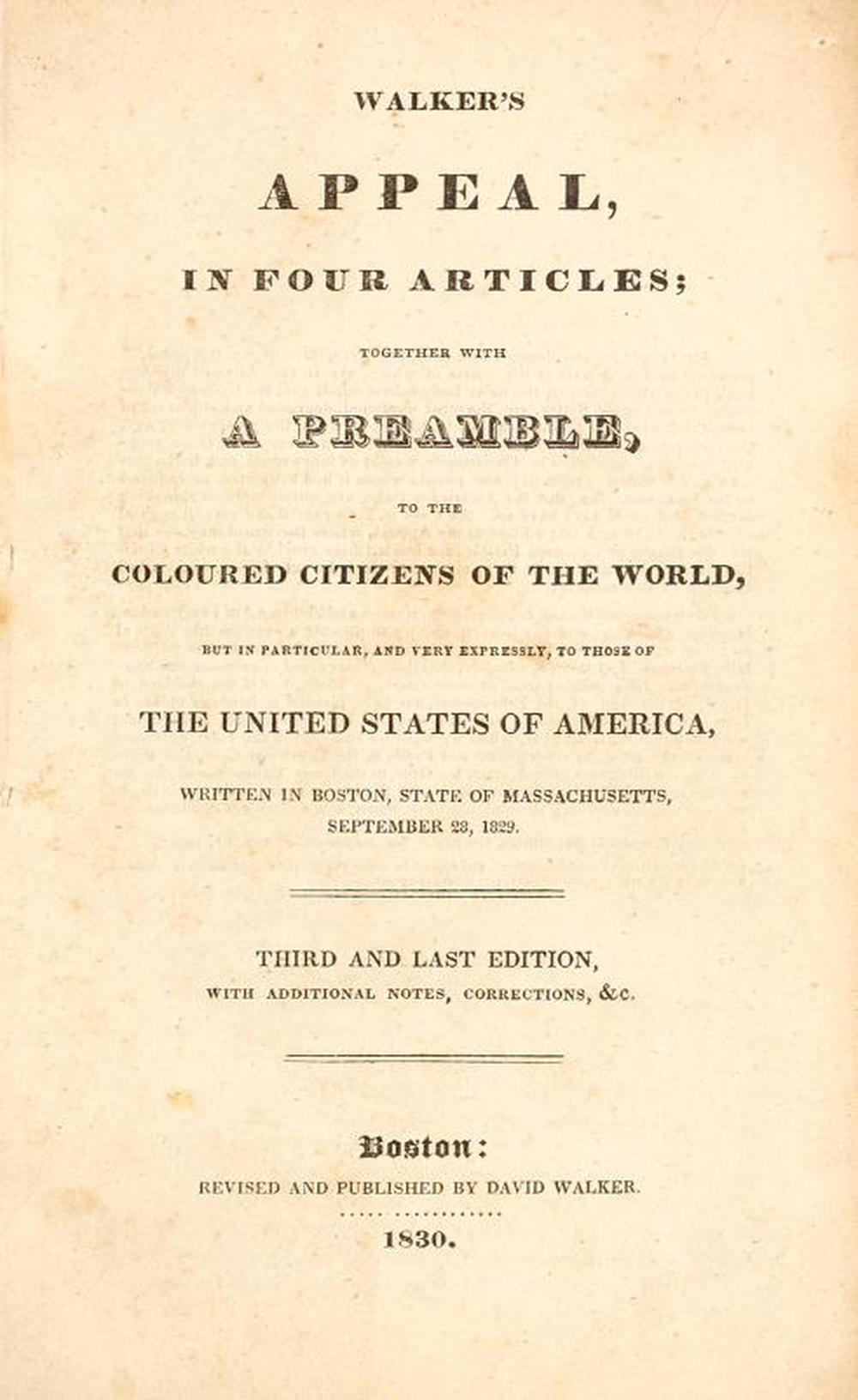

When Hosea Easton gave this speech, he was deep in an effort to organize the free black community of Boston. He had recently moved to the city and become immersed in the abolitionist activity of Beacon Hill. There he met the men with whom he would found the Massachusetts General Colored Association, one of the earliest and most storied all-black abolitionist organizations. The founders included the black abolitionist David Walker, who would rise to national prominence (or, in the South, regional notoriety) and bring the group historical acclaim. Born free in North Carolina in 1796, Walker came to national attention when he published An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World in 1829. The Appeal called on enslaved people to rise up, and its insurrectionary message was felt to be so dangerous by Southern legislators that they banned it. Vigilante slaveholders put a bounty on Walker’s head.

In the sections directed at free persons of the North, the Appeal promoted the kind of organizing the Massachusetts General Colored Association engaged in. This theme was one Walker had been working on since at least December 1828, when he addressed the association at its first semiannual meeting in a famous speech known as “The Necessity of a General Union Among Us.” Delivered within a month of Easton’s address at Providence, Walker’s speech in Boston covered many of the same points. It advocated for moral uplift and community organization, which Walker believed were the means to ameliorate what he called the “hereditary degradation” of racism and slavery—the notion that white supremacy and racial terror had transformed the very nature of black Americans and that these unwelcome changes were passed down to future generations. The two men’s speeches—one celebrated in the annals of abolitionism, the other all but lost to history—are uncannily similar. But perhaps this should come as no surprise. They had been working together for months.

Hosea Easton spent the final year of his life writing the only other text of his we have, A Treatise on the Intellectual Character, and the Civil and Political Condition of the Colored People of the U. States. If his 1828 address at Providence was a scathing denunciation of racist behavior by white Northerners like the congregants in Stoughton, then his 1837 Treatise was a rebuttal to the church’s elders claim that nature was organized by a series of unchanging and all-determining gradations, and that social hierarchy simply reflected what nature had made.

By 1837 this claim, voiced by Stoughton’s elders as a biblical truth, had taken on new life as a supposedly scientific one. The years between James Easton’s birth in 1754 and Hosea Easton’s death in 1837 saw a dramatic shift in the way white men working in the natural sciences defined race. The centuries before had seen race—or “variety,” as it was most often called—defined as the outcome of a dynamic relationship between human bodies and the environments they lived in. Climate theory reached all the way back to ancient Greece, with texts like “On Airs, Waters, and Places” of the Hippocratic Corpus, which proposed that the “forms and dispositions of mankind correspond with the nature of the country,” and sought to pinpoint which particular environmental factors caused which particular human form. In this paradigm, human variety was thought to be highly contingent and human bodies essentially malleable according to climatic features. By the middle of the eighteenth century, however, philosophers, statesmen, and slaveholders across the Atlantic world were redefining race not as the consequence of a people’s environment but as a somatic essence that transcended climate. Kant called it Keime, or germ—a property of the body’s deepest interior that expressed itself in a wide array of anatomical characteristics and cognitive endowments, none of which were changeable.

This ascendant theory of race as biological was formulated and embraced by slaveholders. Thomas Jefferson, in his 1785 Notes on the State of Virginia, wrote that he was not sure “whether the black of the negro resides in the reticular membrane between the skin and scarfskin, or in the scarfskin itself; whether it proceeds from the color of the blood, the color of the bile, or from that of some other secretion.” A modern reader of this list might wonder what “scarfskin” is or what “other secretion” Jefferson might be speaking of—but the truth is that Jefferson did not know. As he guessed where race “resided,” Jefferson offered a series of half-invented anatomical features for its bodily location. His equivocal list implies that Jefferson had no idea what race was or where it was located, which makes his conclusion all the more strange: he was nevertheless certain that race was contained inside the body and “fixed in nature.” In the decades that followed, the scientific establishment worked to supply the empirical proof of this difference and give evidence for slavery’s rightful basis in some natural, permanent hierarchy.

Easton’s Treatise directly confronted the biological theory of race. The abolitionist’s central claim was that “no constitutional difference exists in the children of men.” Humans had become variegated, he wrote, but the cause of this variegation “cannot be found in nature.” Where, then, and how? For Easton, the mechanism of racial differentiation was to be found in the “incidental circumstances” of human life—that is, in human history. It is easy to miss the scientific nature of Easton’s Treatise because so much of it is spent on discussing the past; the bulk of the introduction contrasts the history of Europe with the history of Africa. But this is exactly Easton’s point: racial difference was not a product of nature. It was a product of history.

In Easton’s telling, European history was defined by war, conquest, and savagery, whereas African history consisted of lavish cultural achievement and peacemaking. This history had turned European-descended people into a “barbarous and avaricious” race. In the modern era, this race had focused its violence on Africans in the form of slavery. The history of slavery was the turning point in racial differentiation, for the brutality of slavery had transformed a once thriving people into what Easton assessed as a “degraded” race. This diagnosis—that black Americans had become “degraded”—could strike us now as acceding to the racism of the white scientists Easton was writing against, a group that would come to be known as the American School of Ethnology. It is true that Easton agreed that race was manifest biologically, that it expressed itself in the shape of the head and nose, in the texture of hair, in a person’s posture and gait. Easton did not argue that the American School misread the signs of race; he argued that they misread the cause, and here is where his assessment of “degradation” assumed its antiracist shape. Whereas the American School pointed to the signs of race as empirical proof of natural African inferiority, Easton pointed to them as visible evidence of racist systems. These systems, particularly slavery, had written themselves onto the very bodies of African-descended people. Easton’s radical, antiracist claim was that everything his fellow Americans thought they were seeing about race was actually about racism. His criticism was not of black Americans as individuals or as a people but of the system that brutalized them.

Easton’s theory shared some conceptual bedrock with the climate theory that had come before, which the ideologues of biological race had worked hard to displace. Easton also represented human bodies as highly malleable, able to undergo massive transformation in response to their conditions of life. As an abolitionist text, however, his treatise retooled climate theory, replacing the all-powerful environmental factors like heat and humidity with human social factors, namely the all-encompassing violence of slavery.

His argument also shared a foundation with the other trend in the sciences that emerged around 1837 and would explode in 1859 with Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species: evolutionary theory. At the same moment that white scientists of race were concluding that race was a transhistorical, unchanging essence, geologists, biologists, and other naturalists were discovering that the opposite seemed true. The years that Hosea Easton was organizing the Massachusetts General Colored Association, 1828–33, were also the years that Charles Lyell was publishing his three-volume Principles of Geology. The Scottish geologist argued that Earth was far older than the six thousand years given to it by the Bible, and that our planet’s surface was subject to ongoing geological change by natural processes that were still at work. Darwin would read Principles of Geology aboard the HMS Beagle and take much from its concept of change over time. At the same time Lyell was writing, French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was developing his concept of “soft inheritance,” or the notion that animals developed traits favorable to their environments and passed them on to their offspring. It was becoming clear that Earth and its living things had experienced great change over a vast timescale, and that these changes were related to the conditions of life in which creatures found themselves. Evolution revealed the idea of an unchanging racial essence to be the elaborate white supremacist hoax that it was—which is what abolitionists like Easton had been claiming all along.

David Walker’s Appeal made this case most clearly. Walker rejected the notion that nature had made African-descended people biologically inferior. He demystified this claim as the work of white statesmen and slaveholders who sought a scientific—thus apparently indisputable—explanation for slavery. It was history, not nature, he argued, that had created racial difference; as Easton would, Walker, too, dedicated much of his Appeal to retelling the biblical and secular history of white brutality—and the racial “wretchedness” among black Americans that had resulted from it. For Walker, as for Easton, race was not the basis of slavery, as Jefferson had so influentially claimed, but the effect.

It is hard not to speculate that the decision by Walker and Easton to attack antebellum race science, as well as the many similarities in their theories of racial differentiation, came out of their time spent together in Boston as antiracist and abolitionist organizers. Their work spurred a concerted effort on the part of prominent abolitionists, most notably Frederick Douglass and Martin Delany, to go after the biological theory of race and debunk it. Douglass picked up their mantle in his 1854 address titled “The Claims of the Negro, Ethnologically Considered,” which promulgated the idea that “the evils most fostered by slavery and oppression are precisely those which slaveholders and oppressors would transfer from their system to the inherent character of their victims.” Douglass argued that slavery and racism had made their stamp on the malleable minds and bodies on which they acted, and he affirmed what Walker and Easton had proposed: that the “condition of men,” not their inherent character, explained the “their various appearances.” Douglass also furthered the political conclusion that stemmed from this oppositional theory of race. If the unnatural systems of slavery and racism had imposed differences where none existed, then the only way back to nature’s equality was emancipation.

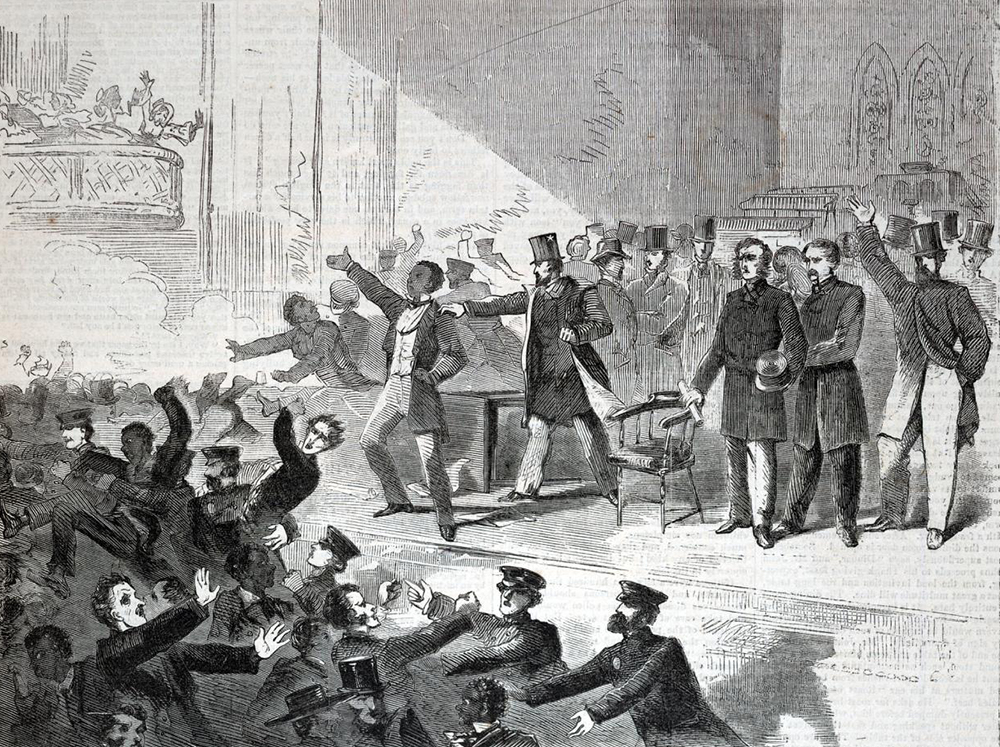

When Douglass wrote these words, he had been free for sixteen years, having emancipated himself in 1838. But he was not free of the racism that pervaded the North and had led Stoughton’s Baptist churchgoers to tear James Easton’s pew out of the floor. In his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, Douglass told of what happened to him when he refused to abide by segregation on a trip up Boston’s North Shore. Seating himself in the whites-only train car, Douglass was seized by six men who told him that if he did not leave the car, they would drag him out. He refused, and they did. “They clutched me, head, neck, and shoulders,” he wrote. This time, it was Douglass who tore out the seats. “But, in anticipation of the stretching to which I was about to be subjected, I had interwoven myself among the seats. In dragging me out, on this occasion, it must have cost the company twenty-five or thirty dollars, for I tore up seats and all.” In the midst of these persistent terrors, abolitionists pulled the floor out from under the scientific falsities built to justify them.