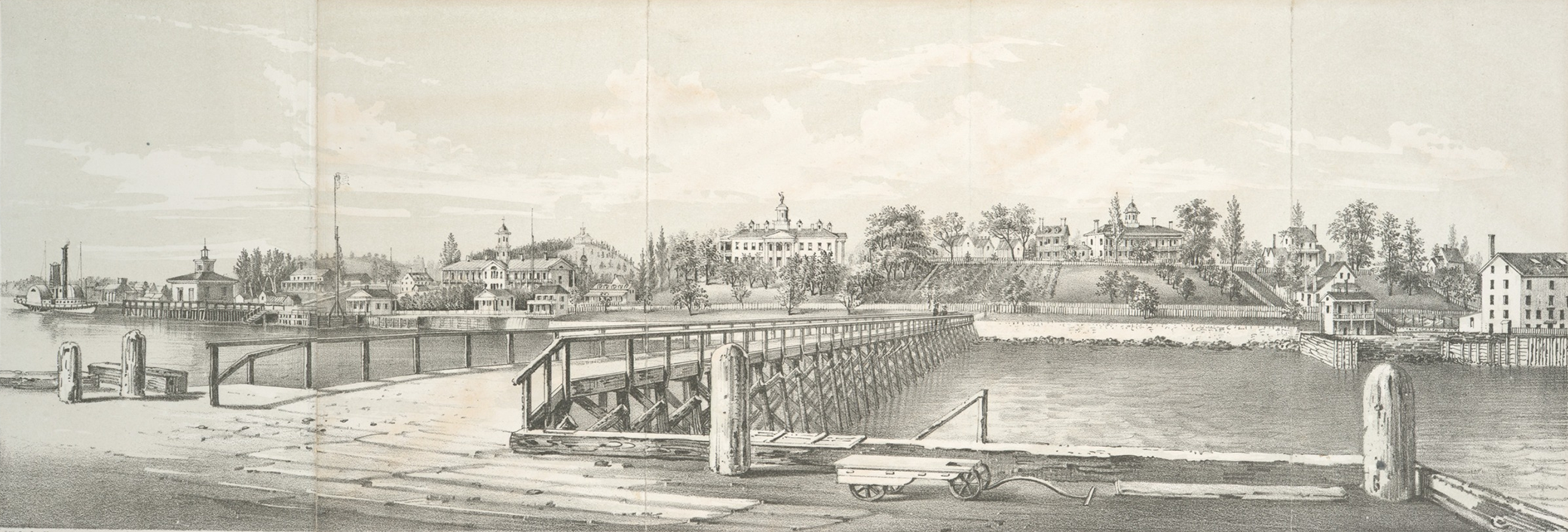

The Quarantine Hospital on Staten Island, by George Hayward, 1858. The New York Public Library, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs.

During the nineteenth century, a period that seethed with typhus, cholera, smallpox, yellow fever, and “black vomit,” port cities like New York were the catch basin through which the world’s sick flowed. These ports controlled the spread the only way anyone knew how: medical quarantines. Staten Island reluctantly hosted the Port of New York’s infected for much of the first half of the 1800s. There are at least three burial grounds on the island for those who died in medical quarantine hospitals.

One burial ground can be found on the corner of St. Marks Place and Hyatt Street in the neighborhood now called St. George, not far from the Staten Island Ferry. The northeast corner of this intersection brackets a municipal plaza of the Richmond County Courthouse. On the overcast day I traveled there in December 2020, the plaza was virtually empty. The number of Covid-19 cases were spiking on Staten Island.

Earlier in the year, I heard a news report that mentioned there were few, if any, memorials to those who died in the influenza pandemic of 1918. It just wasn’t the sort of mass death that lent itself easily to memorialization. I wondered if or how we would memorialize our own pandemic. Soon thereafter, I stumbled across a blog post about the burial grounds—and memorials—dedicated to those who died in nineteenth-century pandemics on Staten Island. I wanted to go see all three sites—the one in St. George, one up the road from there, and one farther south along the coast called Seguine Point—thinking maybe I would glimpse into our future. I was also tired of being inside and wanted to get out for a walk.

In the center of the courthouse plaza is a mangy patch of grass, maybe twenty by thirty feet large and rimmed with sidewalks. Near the center is what looks like a gravestone. Underneath a recessed Catholic cross it reads in memory of the innocent victims of the irish famine 1845–1851. The marker is off center and quite small relative to the size of the patch of grass. It feels slightly out of place and inadequate; a single gravestone implies a single death, when this clearly isn’t the case. The small marker struggles to encapsulate the wave of death caused by the Irish potato famine that crashed on the shores of Staten Island. Near the gravestone is a much larger sign that reads marine hospital quarantine cemetery 1799–1858. These signs appear related, but already the dates raise questions.

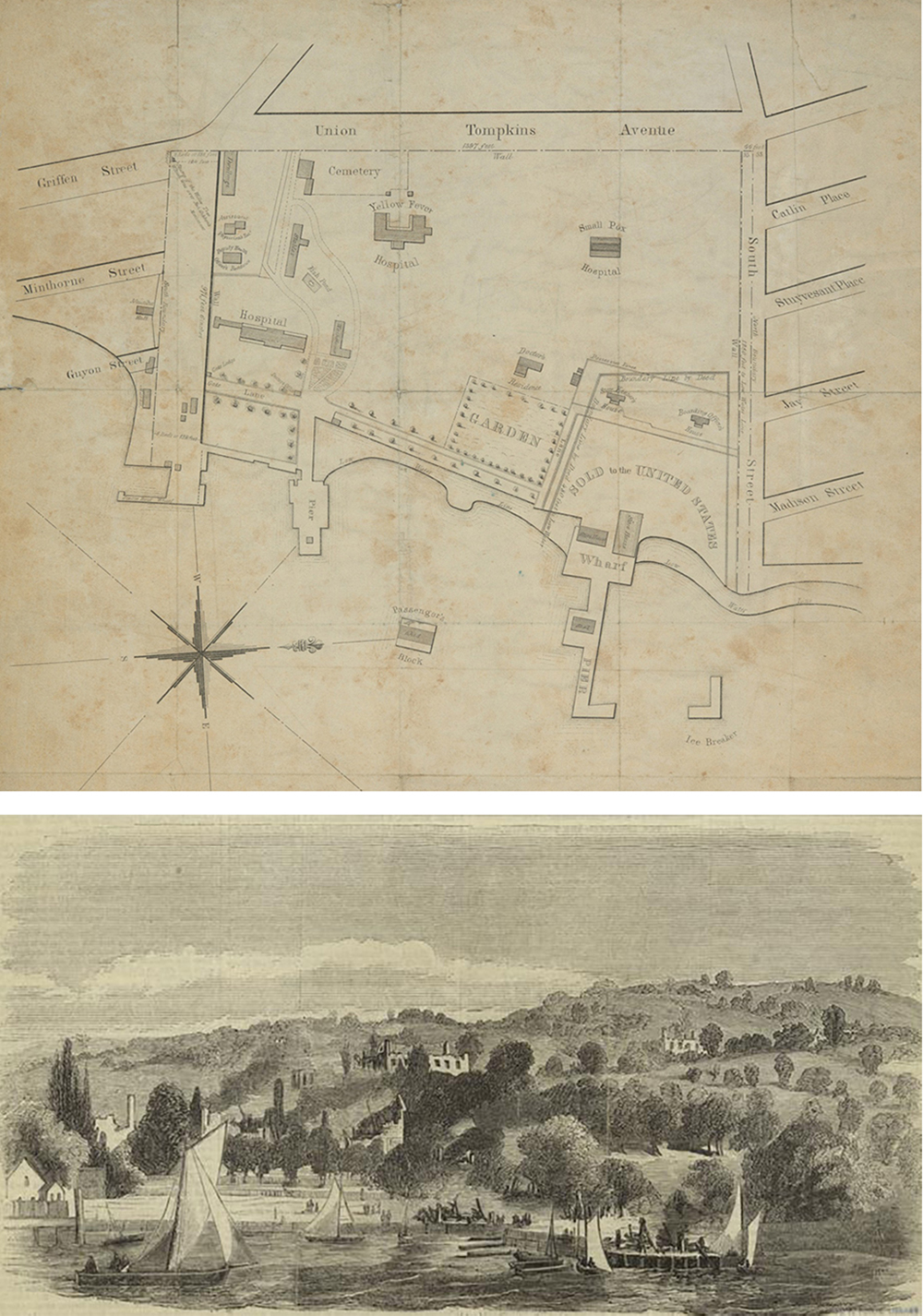

In the nineteenth century, the area occupied by the courthouse housed the locally infamous Marine Hospital, a medical quarantine. This complex of buildings, built on the site in 1799, treated the contagious masses that came through New York, rich and poor alike. The reigning theory of disease transmission at the time was ghostly and gaseous; medical professionals argued that illness emanated from odors, the humidity of steerage, and the stew of marshes. It was carried by winds and in the sheets of the sick. The only effective cure, according to the latest science, was containment.

Up until the 1840s the complex served only a slow trickle of the sick, about five hundred patients a year. Almost from the beginning, neighbors fearing infection complained, to no avail. The arrangement festered. Then the fire-hose spray of European immigration—spurred in part by the Irish famine—flooded the hospital and the surrounding neighborhood with patients. The pitch of islanders’ consternation grew considerably. By 1849 seven thousand people moved through the Marine Hospital per year. Before undertakers had hauled the dead up the road to the Marine Cemetery, near Silver Lake. But during this wave of immigration, so many people were dying that officials directed workers to cut graves on the Marine Hospital’s grounds to bury the dead. There was not enough room for single graves, so three or more bodies filled each trench. In the three years the mass grave operated, from 1847 to 1850, it’s possible that three thousand bodies were buried in the ground under my feet.

The Marine Hospital was unsurprisingly deadly for the hospital’s workers. Budget reports list funeral expenses for employees as their own line item. In 1850 the hospital purchased 556 wooden coffins. In 1856, a year with a deadly yellow-fever outbreak at the Marine Hospital, thirty-three workers came down with the virus, including five nurses, four orderlies, and a cook. Contemporary maps of the grounds show a separate graveyard for employees down the hill from the plaza.

I walked downhill on Hyatt Street toward Victory Boulevard, looking for any sign of the employees’ gravesite. In the middle of the block, inexplicably, is a gigantic pit that’s gone to seed, bordered by a chain-link fence. Marshy plants abound. The pit appears to be a municipal quagmire unrelated to the burial sites, but I estimate the cemetery was located in the southeast corner, next to a day care, a check cashing store, and a Domino’s Pizza. There are no historical markers of what was, or still is, here.

The burial site up the hill on St. Marks and Hyatt, with its single gravestone in the courthouse plaza, is the result of an archaeological survey and disinterment that began in 2003. The remains that were recovered were placed in coffins and reburied in a concrete vault under the patchy grass. I am skeptical that everyone buried there was Irish, as the gravestone implies through omission. How could they be? Immigrants from all over the world came to New York in the nineteenth century, not to mention soldiers coming back from the Spanish-American War with yellow fever.

Then again, that gravestone doesn’t preclude other ethnicities and other stories buried in the crypt. It just expresses the prerogative of whoever arranged this contemporary memorial. But maybe this is the only way we memorialize something that is almost unmemorializable: a gigantic collection of assorted unidentified bones. These bones become a proxy for the tragedy of the Irish famine but cannot also carry the memory of the five or six diseases that randomly washed over the world in the nineteenth century. It’s why we have infinitely more memorials for 9/11 than for the victims of yellow fever. Memorials rarely pay homage to people—they use people to pay homage to ideas.

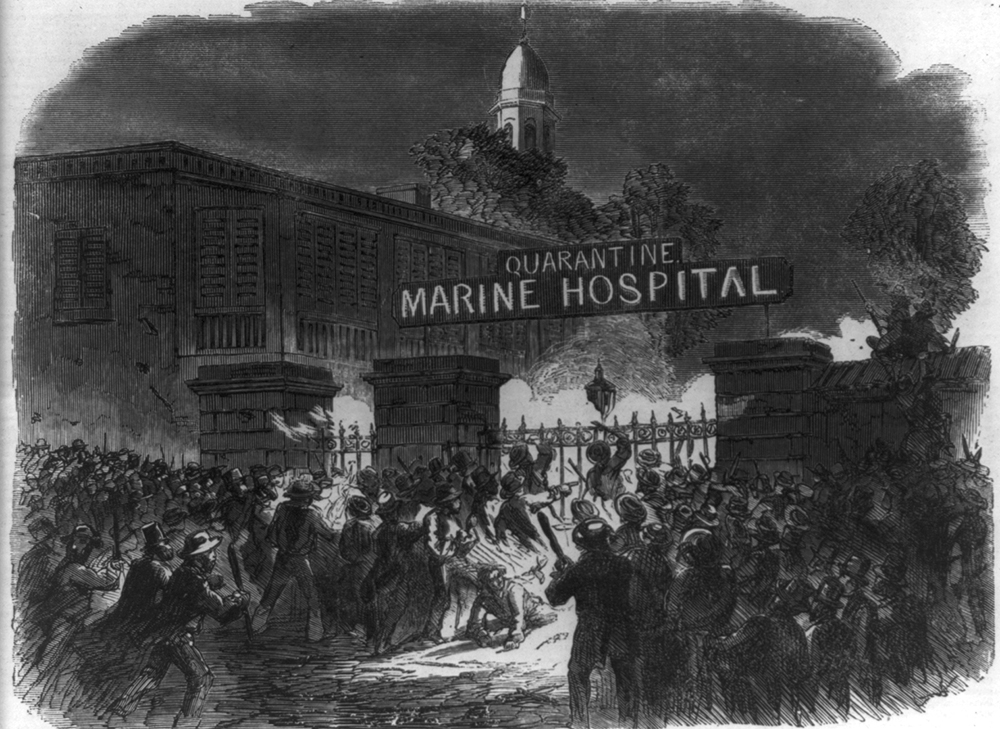

Once immigration to New York tapered off in the early 1850s, unclaimed bodies from the Marine Hospital were once again taken up the road to the Marine Cemetery. As they were wheeled past Staten Island homes, their inhabitants grew increasingly alarmed by the idea of living in the wake of diseased corpses, spouting their miasmas of germs. These fears would continue until residents found a direct but radical solution that cut out the root of their problem: they burned the Marine Hospital down in 1858.

The annual number of patients treated at the Marine Hospital complex was down to the low hundreds by 1858, but the villagers had had enough. On the night of September 1 a mob stormed the six-foot walls with mattresses full of straw and flammable camphene. What didn’t burn the first night, they came back and lit the second. A stevedore shot another stevedore to settle a grudge and an ailing patient passed during those two nights, but no one died as a direct result of the blaze. After the compound was reduced to smoldering rubble, it was never rebuilt. The Marine Cemetery at Silver Lake essentially ceased operations, too.

But the burial plot near Silver Lake was still there. Throughout the rest of the 1800s, the Marine Cemetery had a fence and a house for the caretaker. Gravestones marked a handful of the dead: William Crowther of London, who died in 1818 of fever while on his way home from Haiti to Philadelphia, and Andrew Staley, a “native of Old England who fell victim to the epidemic fever” in 1805. A 1923 site survey showed that twenty-four tombstones remained, which I calculate to be less than half of a tenth of one percent of the total number buried. The Marine Cemetery was then swallowed up by the new public Silver Lake Park in the 1920s. When the city then turned a portion of the park into a golf course, the surviving gravestones were buried in the process of terraforming the links.

My self-guided tour took me there next. Layered over the land where all the dead were buried is the eighteenth fairway. Right beyond the golf-cart parking lot and next to a sand trap is a boulder that sits on paving bricks; behind it is a blue spruce and a flagpole with an American flag, an Irish flag, and a Parks Department flag.

On the rock is a plaque that reads

the forgotten burial ground 1849–1858

here lie the unmarked graves of irish immigrants who fled the great famine in search of freedom. those who are buried here died from disease, alone and isolated, in the tompkinsville quarantine before ever tasting freedom. the 7,000 dead, most of whom had no survivors who could afford markers, were buried anonymously. they will never be forgotten.

2002

Here, once again, are conflicting dates and figures, suggesting that the cemetery was only open from 1849 to 1858 and that there are seven thousand dead, a number I haven’t seen elsewhere. While it is wonderful that someone has recognized the thousands of people probably buried beneath the golf course, it notably revolves around a certain strain of Irish identity. One effective way to remember messy, sprawling catastrophes is by sorting out the dead into different buckets. It slices away at the vines and weeds that make human death an unwieldy, largely ungraspable abstraction. To remember, we reduce the story to one that the living can relate to. Clearly someone needed this story, this memorial, to exist, though I can’t say who. It might not matter if the facts aren’t perfectly straight.

After 1858 ships still needed a place to send infected passengers, and people without family or money continued to die on the various islands in New York Bay that still quarantined the sick. Though the state stopped using the Marine Cemetery, they continued to bury bodies elsewhere on Staten Island. Officials sent diseased corpses to a burial ground on a marshy lowland on the southeastern coast now known as Seguine Point.

As a burial ground, Seguine Point was as hotly contested and despised by its neighbors as any other. The plot had been the proposed site of a quarantine hospital to replace the compound farther north in Tompkinsville. The state even started construction on a new building in 1857, but the locals torched the nascent structure. They also destroyed the pier, hoping to further inhibit the use of the site. This spate of destruction inspired the pyromania in Tompkinsville of the next year.

When a New York Times journalist traveled to the site in 1882, after it began serving as a burial ground, he could not find a carriage that would take him from the train station to the beach. Locals didn’t dare go near it. The plot was neighbored only by farms. He walked muddy roads until a passing driver agreed to take him as close as half a mile. Upon arrival the reporter found a “desolate” scene. Not much more than cheap wooden tablets marked the graves. A fallen tree lay among the plots. He met a man fishing near the site who told him that he often saw people pull up in tugboats, dump the coffins in graves, cover them with dirt, and leave without a prayer.

In 1890 the state decided to get rid of the graves at Seguine Point. Officials hired a dredging contractor named Mr. Flannery to exhume the bodies and cremate them on site in an ad hoc brick oven. A series of articles in the New York Herald captured the careless and grisly process. As hired men dug up corpses, often a leg or arm would fall off. “Without the slightest hesitation,” reported the Herald, “it would be thrown with the rest of the body,” much like a fruit vendor tossing an apple back onto their cart. The grave diggers hooted with delight when they found gold and jewelry. Flannery failed to get the crematorium running for the first couple days, so bodies were piled in an open pit. Residents complained of the smell. By the third day, the brick oven was functioning. Workers, who had been sleeping in the graveyard in a crude shack, eating beans and macaroni cooked over a fire, began to incinerate the bodies. The process was not smooth, and the number of grave diggers dwindled, causing the foreman to ply the remaining men with whiskey.

Every body was supposed to have been exhumed, cremated, and buried on Swinburne Island, just off the coast from Seguine Point. But not everything went to plan and the remains didn’t all get buried; the crematorium blew the ashes out to sea. But after reading the Herald’s account, I can’t be confident the contractor got every last body from this poorly maintained and haphazardly organized cemetery.

Today, the burial ground at Seguine Point is covered by Wolfe’s Pond Park, a large recreational area with a rocky beach. As I walk on the beach, the tide is out and pairs of men with boots and pitchforks dig up rocks in search of bloodworms for bait. Flocks of Brant, down from Canada for the winter, honk and dive for food just past the shore.

I push up from the beach through a thicket of seagrass, northern bayberry, and phragmites to what contemporary maps call the “BBQ area.” In the place of the old burial grounds is a wide-open field, quite flat, with picnic tables. There is an intentional-seeming diversity of trees planted at unimaginative and awkwardly even intervals; sycamores and red oaks mix with paper birches and ginkgos. Goose mess carpets the squishy grass. The only other people in the BBQ area are two middle-aged women with matching red hair and red jackets sitting more than a hundred yards away.

It is more than likely that there are human remains buried in this marshy BBQ area, yet there’s no memorial. I am also suspicious that there are Marine Hospital employees buried near the day care in St. George, because I cannot find any records of disinterment. News reports suggest that developers disturbed the on-site quarantine graves at least twice in the twentieth century, once as recently as 1957 when the corner where the plaza now stands was turned into a parking lot. One local claims that during construction she once saw a dump truck full of bones. She followed it to the water and watched as the contents were emptied into the harbor.

I found a number online for the group responsible for the lone gravestone at the courthouse and dialed. A woman on the other end of the line answered and was surprised when I told her I was writing about the island’s forgotten quarantine burial grounds. She said, emphatically, that “it is absolutely no secret that there are quarantine burial grounds on Staten Island, every history book mentions them.” Then she said she wasn’t going to talk to me on a cell phone and hurried off the line. I felt a little silly for thinking I might find a latter-day facsimile of the abandoned cemetery caretaker Mr. Hunter, from Joseph Mitchell’s 1956 story. Mitchell’s character is warm, nostalgic, and happy to talk at length. My memorialist was not interested in me and my own petty investigation into the incompleteness of memorials. She protects and rehabilitates abandoned cemeteries, and maybe that was enough. You can’t interrogate the desire to protect abandoned graves too much because it is a bottomless task. Do we need to keep clean and protect all graves for all of time? Of course not. We just do what we can. We establish tributes as an expression of our own thin, fleeting dominion over history.

Never forget, we often say, knowing all the while that we must forget in order to function on a daily basis. Cemeteries, while so solid-seeming, are just blips in the slipstream of history, an attempt to control time and hoard memories that we all know will fade. Soon they’ll be covered in a layer of sediment. Most of the ten thousand people who died of infectious diseases on Staten Island in the nineteenth century are and will be forgotten. We claim to remember them when it is useful to the present, as it must have been in 2002, when someone decided after almost seventy years that they would publicly re-remember the burial grounds. Cultural memory, clearly, is not contiguous. The past is a mess.

During the coronavirus pandemic, Staten Island once again has to deal with the interment of unclaimed bodies of plague victims. In April 2020 the public administrator for Richmond County announced that five people who had died of Covid-19 were still unclaimed. If they weren’t spoken for, they would be buried at one of four cemeteries, based on their religion. The Associated Press reported a story at the same time about Mount Richmond Cemetery, where Jews who die poor or unclaimed are buried. “A century ago,” according to the article, the cemetery “buried garment workers killed in the Triangle Shirtwaist fire and those who fell to the Spanish flu. More recently, it was Holocaust survivors who fled Europe.” The cemetery has struggled to keep up with burials during the Covid-19 pandemic, burying almost ten times as many people as usual.

At the time I was walking around Staten Island, more people were dying in the borough than anywhere else in the city, much like in the late 1840s. Richmond County officials worked to make sure Staten Islanders were buried on the island and not sent to Hart’s Island, the city’s main cemetery for unclaimed bodies.

But without a site like the Marine Hospital, that choke point and locus of disease, the bodies of Covid-19 victims will simply be scattered among the rest of the dead. Their gravesites will not become a place to collectively mourn our experience of mass death. Every Staten Island history book will likely mention the coronavirus pandemic, and many might mention the borough’s attempt to keep the bodies buried on the island. But will we remember? What remains of nineteenth-century gravesites suggest that we will, but only if we need to.