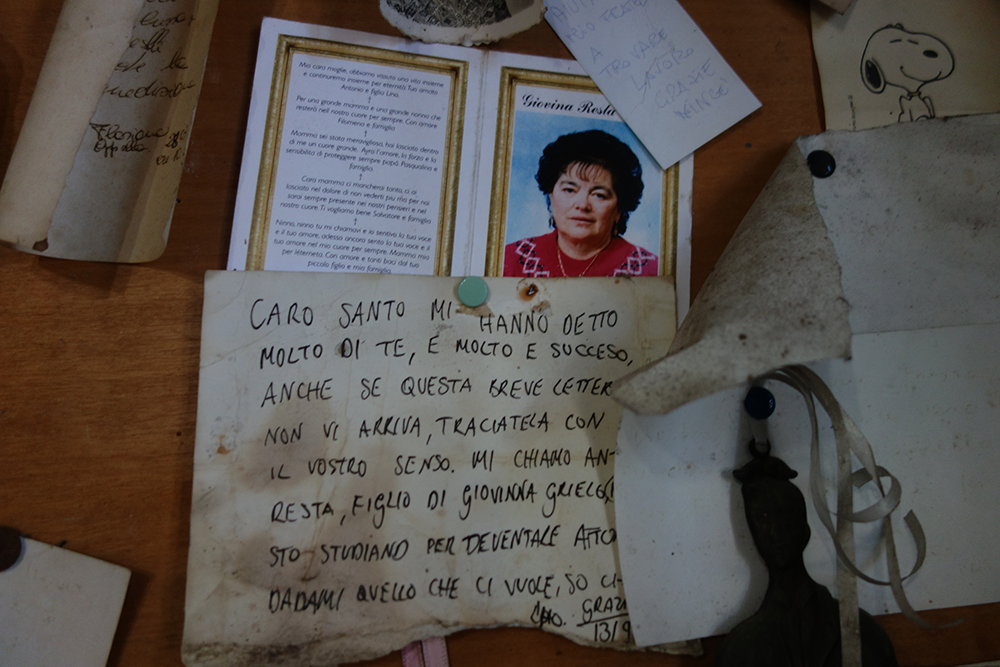

Photographs left by those who have prayed to Uncle Vincent. Photograph by Elizabeth Harper.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

Traffic lights dot the streets of Naples like rhinestones. I’m not being romantic—I mean they’re shiny and worthless. Locals telegraph their unwillingness to stop on red with the internationally understood middle finger, which means tourists like me learn quickly that Neapolitan traffic isn’t ruled by lights or laws. It obeys the sea of motorbikes. Cars go when they go and stop to avoid vehicular manslaughter. Renting a car here wasn’t sensible, but it was the only way I could get to Bonito, where I had made an appointment to meet its most powerful and reclusive resident: a naked mummy named Zio Vincenzo Camuso, or, in English, Uncle Vincent.

Bonito is tiny. It’s not much more than twelve streets on top of a hill surrounded by Campania’s farmland. As soon as I turn off the dirt road onto the city’s cobblestones, a sign with a cross and arrow points me not in the direction of the parish church but toward Uncle Vincent’s shrine, a yellow stucco building that’s a little too big to be a mausoleum and a little too small to be an apartment. I borrow the key to the shrine from city hall and park across the street. I watch as two men in a garbage truck drive by: one makes the sign of the cross and the other tips his hat to the shrine’s iron door.

As soon as I’m inside, the reason for their reverence is clear. Uncle Vincent is known for granting miracles. Photos and gifts from grateful recipients are stuck to every wall and stacked in every corner. There are rosaries, electric candles, potted plants, and ribbons, and baby clothes and thank-you notes from women who asked for help in childbirth. There are hundreds of flat metal charms called ex votos left by people whose prayers to Uncle Vincent have been answered. Sometimes the charms represent the thing they asked for—a baby or a computer—but mostly they depict body parts that have been healed. On one wall a copper leg is pinned to a corkboard next to a picture of a smiling man with his leg in a cast. There are metal eyes, breasts, hands, guts, hearts (both the sacred and the anatomical variety), and even a paunchy belly. A photocopied page of local lore at the shrine describes how hands-on Uncle Vincent can be when he grants these medical miracles. Some people believe he operates on his devotees in their sleep, leaving them cured but with a telltale scar to prove that the work’s been done.

On the left side of the shrine is a marble niche containing the seated body of the man himself. The Plexiglas door between us has knee-high vents; I could kneel down and whisper my prayers to him if I wanted to. But I wonder if he could hear me—his ears are a little caved in. His skin is dusty brown and drapes over him like a limp paper bag, curling around whatever cartilage it finds. The bone on his chin is bare and the flesh on his cheeks sags so much it looks like he has a handlebar mustache. His ribcage peeks through his open sternum as if his skin were a shirt left casually unbuttoned. Combined with the flesh mustache, it gives him a 1970s look that I find kind of charming. He is conspicuously missing the tips of his toes. Thanks to the positioning of his hands in his lap, he is less conspicuously missing his penis, which was deemed immodest and amputated sometime before 1957, when its removal was mentioned in a letter from the archpriest of Bonito.

As an American, I find the sight of a corpse displayed like this a little shocking, but it isn’t so unusual. Catholic churches, particularly in Italy, often display the corpses of saints. In shrines like Uncle Vincent’s, I’ve seen skeletons in formalwear lying in Sleeping Beauty caskets, and gilded boxes containing holy hearts, tongues, heads, arms, toes, and almost any other body part imaginable. The reason is relic veneration, a type of prayer where people ask for a saint’s help in convincing God to answer their prayers. Because a mystical union is believed to exist between saints’ bodies on earth and their souls in heaven, the places where saints’ corpses (or at least parts of them) are kept become a kind of portal between heaven and earth. Plenty of churches are strewn with the holy dead.

According to the Catholic Church, saints (and their bodies) don’t actually have the power to grant miracles—only God can do that. But that isn’t reflected in the way relic veneration works in practice. Many Italian Catholics pray directly to the saints and rely on them to intervene based on their specialties. Some of the more common requests might sound familiar. If you’ve lost your keys, pray to Saint Anthony of Padua, patron saint of missing things. If you need to sell your house, pray to Saint Joseph the Worker and bury a statue of him in your yard. This is the tradition that also leads people to pray to Uncle Vincent.

Technically, the church rejects the idea of praying for direct intervention, but the clergy has a history of looking the other way to avoid alienating otherwise devout Catholics. In the gray area between folklore and orthodox Catholicism, these relationships with saints often become transactional: mortals promise prayers and offerings (such as ex votos) if the saints deliver what they need. But sometimes the prayers go unanswered. In America that’s when the faithful talk about “God’s plan,” but in southern Italy, they might just ask a different dead guy.

When a saint doesn’t respond at first, the petitioner may assume the saint is too busy. In that case, one option is to threaten the saint with replacement. (The citizens of Naples tried this in 1799 when they threw the bust of their formerly beloved patron, Saint Gennaro, into the sea after his dried blood miraculously liquefied in the presence of a French general and seemed to consent to the occupation of Naples. The citizens briefly replaced him with Saint Anthony, who proved ineffective against a volcanic eruption and was fired as well.) But if that doesn’t work, there’s another option that’s even more extraordinary. The petitioner may set her sights a little lower and direct her prayers to a soul in purgatory—a place where flawed souls on their way to heaven are purified in fire. The hope is that since the souls of these regular people are more plentiful and receive less attention than the saints, they will be happy to hear any prayer directed their way. They may respond even faster and be more likely to grant favors if the living also pray for a little refrisco for them—a temporary relief from the flames of purgatory that is supposed to feel like a cold drink on a hot day. It’s a perfectly logical solution: when the demand for Catholic souls in the afterlife is too high for heaven to accommodate, add to the supply by including souls in purgatory.

This is where Uncle Vincent is, spiritually speaking; people in Bonito generally believe his soul remains in purgatory. Yet the official doctrine of the Catholic Church says purgatory is only a temporary stop in the afterlife, one that souls usually try to hurry through. In orthodox Catholicism, people pray for the souls of people they know in purgatory in hopes of getting them into heaven faster; they never pray to them. In folk Catholicism, however, you don’t ask for favors and offer refrisco to the souls of people you know. Instead you pray to souls like Uncle Vincent, the purgatory lifer (or afterlifer).

In southern Italy, especially around Naples, there’s a persistent folk belief that if the names of the dead are forgotten, their souls can’t be prayed for and hurried through purgatory. These unlucky souls remain there forever, but it is believed they are particularly effective in answering prayers if contacted by the living—either through prayer or through the adoption and care of their anonymous remains. This is a helpful tenet in a region that has a lot of forgotten, nameless bodies heaped on top of one another after four hundred years of earthquakes, shellings, volcanic eruptions, floods, and plagues. Go into one of the caves around Mount Vesuvius and you’ll probably find a pile of potentially helpful new friends.

Vincenzo Camuso is one of these powerful but anonymous souls because Vincenzo Camuso probably isn’t Vincenzo Camuso at all. He was named long after he died, and there’s no record of where his name came from. No one is even sure when he died—it could have been the late 1600s or early 1700s based on a description of a confraternity robe his corpse used to wear. But he might have died as late as 1822, when a local court record mentions a Vincenzo Camuso who was charged with theft and general mayhem. Or maybe he was the Vincenzo Camuso from 1722 whose name appears in town records for making a payment on a vineyard. These theories assume that Vincenzo Camuso was his real name, but it could have been the name of the person who found his body or a name inscribed in a crypt that actually belonged to someone else.

What’s certain is that Vincenzo’s body is stuck in the seated position because Bonito’s Brotherhood of the Good Death was responsible for his burial. Members of this confraternity charitably cared for the town’s dead before undertaking was a secular profession. They were the ones who originally brought Vincenzo’s corpse to their crypt at the Oratory of Santa Maria Annunziata, where they placed him in a putridarium—a room where multiple corpses were left to rot on strainer seats until nothing but bone remained. The bones were supposed to be transferred to a final resting place after the decomposition process, but Uncle Vincent mummified instead—a curious but not uncommon occurrence, given the region’s arid climate—so he never made it that far.

The Brotherhood of the Good Death operated for hundreds of years in Bonito, which means the only clue their involvement offers is that Vincenzo must have died sometime before 1849—the latest date the putridarium was used in Bonito, before Napoleon’s public health codes took effect. The French were repulsed by the Italian tradition of leaving corpses to rot in church basements, leading Napoleon to issue the Edict of St. Cloud in 1804 and force churches to abandon their crypts. But the law wasn’t observed until 1849, when all bodies began to be sent to the cemetery just off the main road on the outskirts of town. The Bonitesi, like many other southern Italians, had been reluctant to give up the putridarium. It allowed for a longer relationship with the dead that mirrored Catholic ideas about the afterlife. The putridarium resembled purgatory: a nasty, liminal space for the purging of sin or flesh. The final resting place for the bones was a private niche or mass ossuary that resembled heaven: clean and permanent. But Uncle Vincent never rotted away and thus never rested in peace—an appropriate outcome for the remains of someone who wound up stuck in purgatory. After mummifying in the putridarium, he began a long posthumous career as human decoration.

In the twentieth century, long after Bonito’s putridarium was retired as a place for bodies to rot, the crypt at the Oratory of Santa Maria Annunziata kept a few mummies and bones around for ambience and to remind the congregation to pray for souls in purgatory. Such human remains had no special powers and were thought to be no different than the crypt’s terra-cotta sculptures of people in the flames of purgatory—just another piece of inspirational decor. During this period, Vincenzo Camuso sat wearing a confraternity robe in a wooden niche alongside a woman who had also mummified. They remained there until the earthquake of 1930, when the woman disintegrated and had to be buried. The quake denuded Uncle Vincent of his robe, but his body stayed seated in his niche.

It wasn’t until 1950 that Vincenzo became unusually popular. The congregation built a new marble-and-brick niche for him, located not in the crypt but upstairs, on the left side of the oratory. On the right they built a similar niche to house the relics of Saint Crescenzio, whose bones were encased in a wax effigy of the boy martyr, beheaded at the age of eleven. The pairing seemed to imply that Vincenzo, a mummified nobody, was equal to a martyred saint. Maybe that’s why rumors began to spread that Uncle Vincent could answer prayers more reliably than Saint Crescenzio. People who prayed in front of the saint’s relics began to report that Vincenzo’s mummy called to them, asking for oil to keep the lamps burning near his niche. By the following year, a rogue priest at the oratory was secretly selling postcards with Uncle Vincent’s picture.

The priest was taking a serious risk. Catholic dogma holds that souls cannot become trapped in purgatory, and the idea of purgatorial souls answering prayers is considered superstitious at best for a layperson and positively heretical for a priest. Nonetheless, a number of churches will be happy to sell you postcards of allegedly miracle-working bones still in their crypts. I bought a few at the gift shop for the church of Santa Maria del Purgatorio ad Arco in Naples, including one of a rhinestone-tiara-wearing skull named Lucia known for finding suitable husbands. These postcards ostensibly help pay for the churches’ preservation, but they also turn what used to be powerful relics into museum exhibits, things of the past that can now be seen only on a tour under a docent’s guidance. It’s hard to interact with the bones spiritually if they’re commodified for tourists. Though they seem to harken to a forbidden form of veneration, in fact they represent a crackdown on the southern Italian practice of worshipping forgotten souls in purgatory.

But in the 1950s devotees of Uncle Vincent treated his postcards like prayer cards and began thanking him for the favors they believed he was granting. At first, Vincenzo’s acolytes kept his oil lamps burning, but soon they had electric lighting installed in his niche. People left gold and silver jewelry, charms, candles, letters, money, and photographs. By May 1962 the local bishop warned that Vincenzo Camuso could be the center of an illicit cult. If the priests wouldn’t move him from the oratory, he would issue a bull and move him by force.

It never came to that. In August 1962, another earthquake hit Bonito. A number of sources claim that this destroyed the oratory where Uncle Vincent sat, but some people deny it, explaining that diocesan authorities ordered the destruction of the oratory despite minimal damage to the building. Given the bishop’s threat, it’s easy to guess why. Saint Crescenzio moved to the new parish church, but Uncle Vincent found another way to persevere. A group of Bonitesi who had immigrated to America paid for the reconstruction of a small part of his old oratory. This is the little shrine where Uncle Vincent sits today.

Despite all the friends and admirers he’s made over the years, Uncle Vincent has a well-known dark side that unnerves me a little when the two of us are alone. When he’s not healing people in the hospital, he seems to enjoy sending people there. Doubt him and he may beat you with a stick or a human bone or push you into a ravine, as he supposedly did to a mason who cursed him while working on the restoration of his shrine. Another supposed victim was the fascist mayor’s wife, who covered him with a sheet because she was ashamed of him. People say Uncle Vincent beat her to death in her sleep and then came for her young husband a year later. It’s a good story, but it’s easily disproved. The mayor in question would have to be Attilio Grieco. He died of a stroke at sixty-seven, and his wife didn’t die until twenty-three years afterward. Uncle Vincent seems like a particularly violent kind of saint, a revisionist capable of exorcising fascism and nonbelievers from the pages of Bonito’s history.

One might wonder if the Uncle Vincent phenomenon is simply a case of mass hysteria—an isolated town that has animated a corpse with little more than the power of collective imagination—but that wouldn’t explain his love of travel. A woman from Catanzaro, a town about five hours to the south, said she had never heard of Bonito until Uncle Vincent visited her in a dream in 1975. He introduced himself and asked her to pray for the salvation of mankind. Another local legend is that his spirit went to Venezuela in 1962, speaking in Bonitesi dialect through a medium at a séance. Uncle Vincent’s appearance at a séance seems appropriate: his democratic appeal, and that of other souls in purgatory, recalls the Spiritualist movement, which popularized the séance and was led by women who lacked access to power in traditional society and religion. In Uncle Vincent’s case, his power can be accessed by people who feel left out of the Catholic Church with its patriarchal and class-based power structure.

I pick up a few prayer cards printed with a midcentury photograph of Uncle Vincent and take the shrine’s key out of my pocket as I prepare to leave. Then I notice a second key on the ring. It is small, as if it belongs to a safe deposit box. The only other lock in the shrine opens the Plexiglas door that separates me and Vincenzo. Now I notice the photos and letters carefully arranged around his body and see the gold necklace that someone had placed in his hands, the thin chain wound around his fingers. I could open that last door, but to what exactly? A violent punishment? A divine favor? Or maybe access to a place where this world and the next seem a little closer. But I don’t need any special powers to get there. I just have to befriend the naked man on the other side. I don’t unlock Uncle Vincent’s door, but I feel a tiny stirring that asks me to keep his lights on as I leave, locking the door behind me.