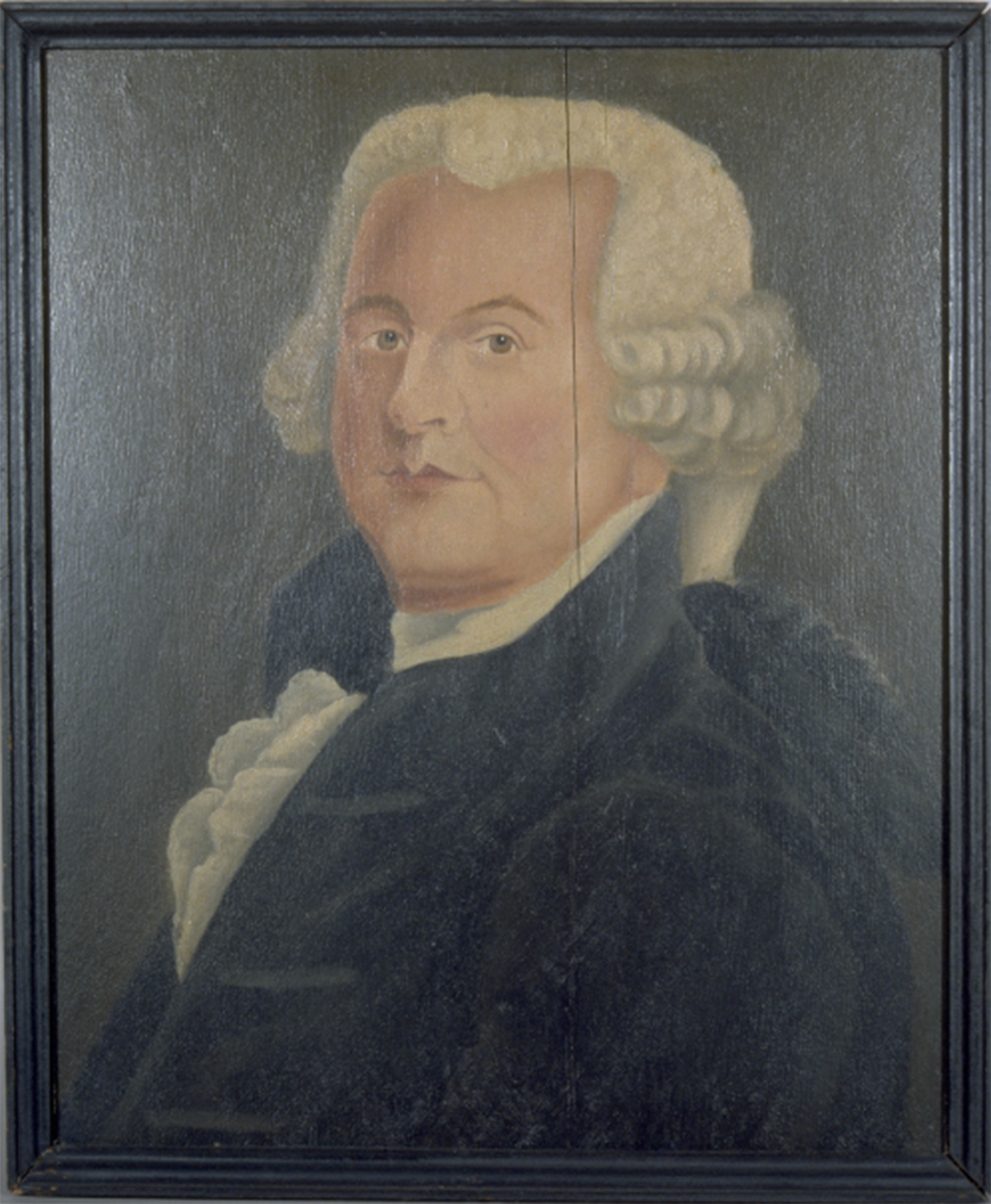

Portrait of John Adams, c. 1800. Historic New England, Gift of Bertram K. and Nina Fletcher Little.

The first indictment and conviction under the Sedition Act of 1798 was of Lespenard Colie of New Jersey; both occurred on October 3, 1798. Though Colie has been described as “a French migrant,” his family had been in New Jersey for over a hundred years, and he was a member of the Presbyterian Church in Springfield, New Jersey. Fragmentary records show him as a teenager holding a farm job, where he was paid monthly and could “go home Saturday Nights & find your own Washing,” and then show him as an adult selling boards and hay. He and his wife Sarah lived in Springfield, ten miles west of Newark, where he paid taxes from 1795 to 1821, and where he advertised a house for sale in early 1798. Colie had been too young to serve in the Revolutionary War, but became part of the Essex County militia. He was described as “very poor,” and ultimately that was the reason for his low fine.

Colie was charged with saying “that if the French came he would join them & fight for a shilling a day, & would deliver up any that were inimical to them—& for D_____g the P________” (damning the president). His statement may have been made during the last week of June 1798, when newspapers reported that some Newark area citizens were “remanded before the Judge of the District Court of the United States” for “having spoken their sentiments on the subject of the President.”

On October 3, 1798, Colie was brought before the United States Circuit Court in Trenton and indicted by the grand jury for seditious words. The presiding judge was Justice William Cushing of the United States Supreme Court, joined by Judge Robert Morris. Cushing had earlier been an associate justice and the chief justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. His wife accompanied him on the circuit, and recorded what Colie was charged with exclaiming.

Justice Cushing charged the grand jury on October 2, 1798, and it then withdrew. The next morning, the grand jury handed down the three indictments for seditious words (the only indictments it handed down that session).

Cushing’s grand jury charge began with the duty to “respect the support of GOVERNMENT,” the “absolute importance” of “orderly government,” and the virtues of President John Adams, including his “unshaken independent spirit of liberty, and eminent displays of genius in the most useful services to his country in the most critical crimes, for above thirty years.” (The typesetting error of “crimes” rather than “times” could have, but did not, lead to its own Sedition Act case.) Cushing lamented the “unceasing torrent of calumnies” about officials that came from a faction and some presses, and asked, “How is it possible for any free government to stand the shock of such perpetual, inveterate, malicious hostile attacks?” He acknowledged the citizens’ “undoubted right to express their opinions upon public matters, in a decent manner,” and he later explained that limitation, saying that liberty of the press does not include “a right to print and propagate scandalous and malicious falsehoods.” As he quoted the Sedition Act, Cushing said that “printing and publishing false, scandalous, and malicious writings against the government, with intent to stir up sedition or insurrection—or resistance to the laws”—was “a dangerous offense in all societies” and could “overturn the freest government in the world.” In defending the law’s constitutionality, he said that “liberty of the press” allowed people “to publish any truths they please” and only prohibited “malicious lies and slander.” Notably, as he discussed liberty of the press, Cushing did not define it as only freedom from prior restraints, such as licensing requirements, or quote Blackstone’s definition.

Colie initially pleaded not guilty, but later changed his plea to guilty. Justice Cushing then sentenced him to a fine of $40 and court costs, but no prison time other than until he paid the fine and costs.

Colie’s case showed that speech critical of the government and its officials would not be tolerated.

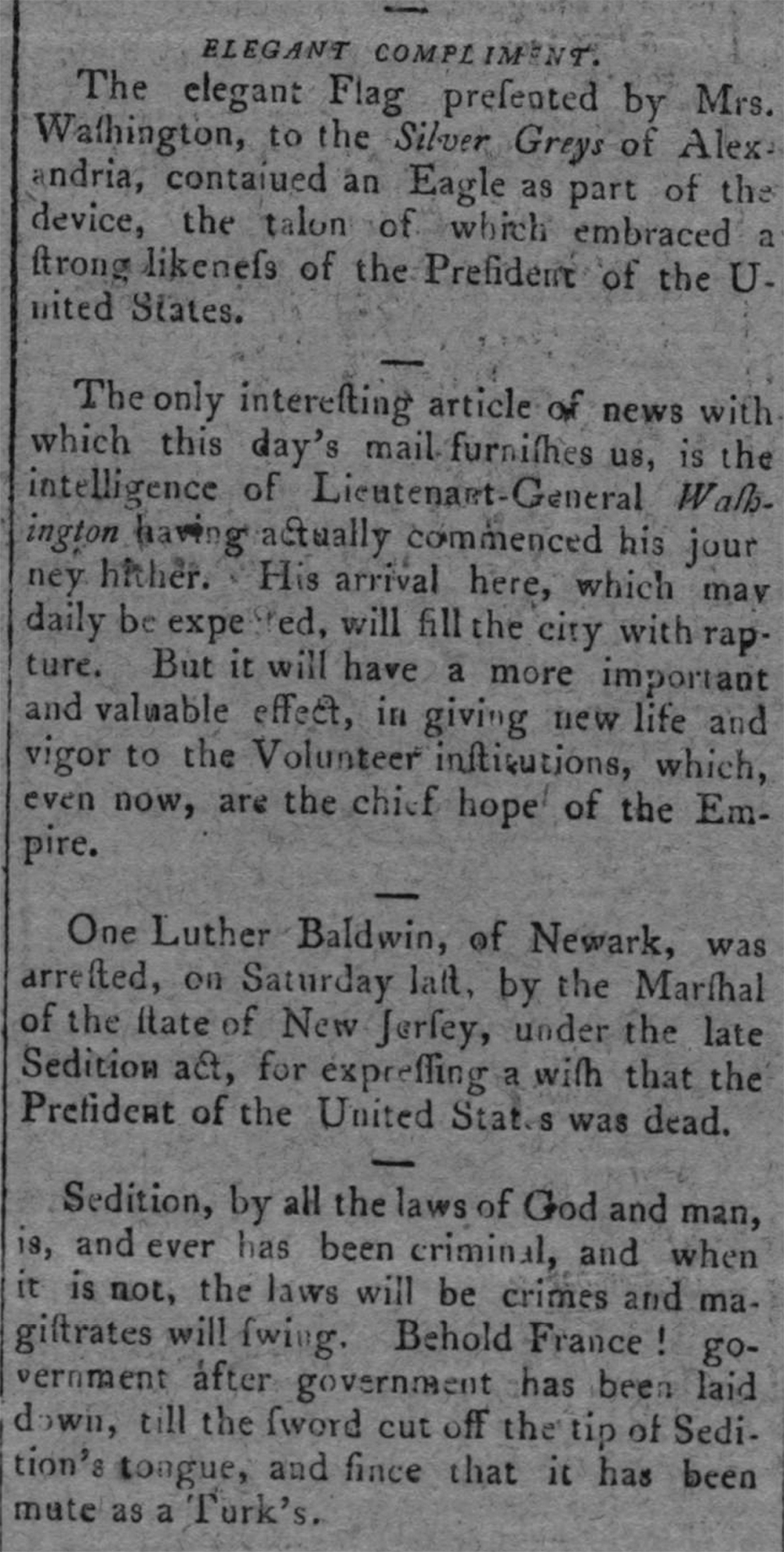

The second and third indictments under the Sedition Act were of Luther Baldwin and Brown Clark of New Jersey, also on October 3, 1798. These three indictments were less significant than the prosecutions of a member of Congress, Matthew Lyon, or of the editor of New England’s leading newspaper, Thomas Adams, both later in October 1798. Instead the Baldwin and Clark prosecutions involved drunken jest in wishing that one of the celebratory cannonballs would hit the president’s posterior. The Baldwin and Clark cases have brought mirth to discussions of the Sedition Act, as historians have solemnly declared that the threat against POTUS (the posterior of the United States) was the “case in which the enforcement of the Sedition Law hit bottom.” Period Republican newspapers were horrified that any Republican would be accused of “firing at such a disgusting target as the —— of J.A.” The English crime of threatening the head of the king was being extended to threatening the posterior of the ruler!

Luther Baldwin and Brown Clark were obscure citizens of Newark, New Jersey. Baldwin’s paternal great-great-grandfather immigrated to Milford, Connecticut, from England in 1639, where he and his children were members of the Congregational church. Baldwin’s great-grandfather moved to Newark, New Jersey, in 1666, where Baldwin’s grandparents and parents later lived. Baldwin was a “wagoner” during at least part of the Revolutionary War, and he paid taxes in Newark during 1779–96. He was described as a “waterman” in his indictment, and used his sloop for odd jobs such as buying and selling hay, repairing bridges when rivers were frozen (charging users a half toll), ferrying passengers across New York harbor, and selling lumber. He was evidently a Republican, because all his business advertisements were in an outspoken Republican newspaper. His death came in May 1804.

Baldwin’s role in the American Revolution became a matter of dispute in 1803, as Federalist papers tired of hearing pathetic stories about his sedition prosecution and went on the offensive. They claimed that Baldwin, after serving on the patriot side for a five-month term, decided the British prospects were better and became a loyalist, carrying on trade with the British, which led to his property being confiscated after he failed to appear at a New Jersey hearing. Republican newspapers responded that he did not desert, that his sale of poultry and eggs to the British in New York City was a cover for gaining and providing information to General George Washington, and that the missed hearing meant nothing because his estate was not confiscated. There were indeed New Jersey spy rings—particularly those led by John Honeyman and by John and Baker Hendricks—though no hard evidence has been found to place Baldwin in one of them. When the Hendricks brothers were arrested by patriot forces, Washington gave orders to “put a stop to the prosecution,” because “they were employed by Colo. Dayton last summer to procure intelligence of the movements of the Enemy,” which was “indispensably necessary.” And they had been allowed “to carry small quantities of provisions and to bring back a few Goods the better to cover their real designs.” The Hendrickses also operated a pair of whaleboats that were authorized as privateers and that required a crew. The truth appears to be the Republican account, because of the response to Baldwin’s petition for compensation in 1790 for war service as a spy. The secretary of war’s report found that his claim to have been “employed to obtain intelligence from the city of New York” had been “established in an authentic manner.”

President John Adams, traveling from the nation’s capital in Philadelphia to his home in Quincy, Massachusetts, reached Newark during the late afternoon of July 27, 1798. The “brigade horse, infantry, and grenadiers” assembled, along with the militia, “marched to the spot where the President landed, and escorted him to his lodgings.” Meanwhile, the artillery company assembled on the Battery and fired “a federal salute,” and other cannon were fired “from the Fort at Governor’s Island, and from the British frigate Topaz” with nineteen guns; and “bells were rang.”

Baldwin, approaching a tavern, heard the cannon discharges honoring President Adams, and exclaimed in a “loud voice” (according to the indictment) that the president “is a damned rascal and ought to have his arse kicked.” He then said, “I wish one of the charges would pass thro’ his arse.” The indictment said this was “to the great scandal and contempt of the President of the United States and government.” A later account, widely reprinted from Newark’s Republican newspaper, plausibly gave the context of Baldwin’s tipsiness and Brown Clark’s minor role:

Luther Baldwin happening to be coming towards John Burnet’s dram-shop, a person that was there [Brown Clark] says to Luther, there goes the President, and they are firing at his a—: Luther, a little merry replies, that he did not care if they fired through his a—: Then exclaims the dram seller, that is sedition.

Unfortunately for the merry duo, the tavern owner, John Burnet, was a Federalist and was on the payroll as a salaried postmaster. He reported the incident to the United States attorney, and was required to post bond to assure his appearance as a witness against Baldwin at the upcoming session of the United States Circuit Court. The prosecution initially was evidently under the common law of seditious libel, like the prosecutions of Burk and Durell, until the indictments on October 3.

Baldwin’s words kept evolving during his prosecution. Federalist newspapers, in delayed notices of his arrest, reported that he expressed “a wish that the President of the United States was dead.” Republican accounts were that “he did not care if the persons who were firing some cannon as the President was passing through the town, were to fire through his body (loaded only with powder).” The incident continues to evolve; some authors describe the case as “the jailing of a drunkard for refusing to stand as the president rode by.”

Baldwin’s and Clark’s separate indictments for seditious words were handed down from the grand jury after Lespenard Colie’s on October 3, 1798. Unlike Colie, they were not in court that day, and so they were arrested and placed under bonds to ensure their appearance at the next court session. In that next session of the Circuit Court on April 2, 1799, both pleaded not guilty and were required to enter new recognizance bonds for their appearance for trial at the October session—Baldwin for $500 and a surety for another $500, and Clark for $500 and two sureties for another $500. Witnesses were also bound over to appear, including John Burnet to testify against Baldwin.

Both Baldwin and Clark changed their pleas to guilty in court on October 3, 1799, a year after their indictments. Baldwin was fined $150 plus court costs, and Clark was fined $50 plus costs, with both being kept in custody until those amounts were paid. The reason for the low fines is that they were “penitent” as “speakers of sedition,” as Justice Bushrod Washington wrote.

These cases were ludicrous, the often anti-Federalist Philadelphia Aurora observed. It was “astonishing how men with common sense could be found to support such prosecutions or juries to recognize such absurd charges,” other than to attack the opposition. Inebriated men had been criminally charged with sedition for their merry banter about harmless blanks.

But these cases showed something far more serious, a political double standard. The local Republican paper protested: “Most of the Papers in the United States, which are violent in advocating the justice of the Sedition Bill, teem with the most virulent invectives against Thomas Jefferson: and yet such editors are unmolested. Why this partiality?” “None of the Federal Grand Juries have ever presented a ‘federal ’ printer.” Republican newspapers claimed that a leading Federalist member of Congress and sponsor of the Sedition Act, Robert Goodloe Harper, said essentially the same thing about the president that tipsy Luther Baldwin had said: “I wish the horses may run away with him and break his neck,” in reaction to Adams announcing new envoys to France. “But why is not this man, that wishes such terrible wishes about the President, arrested and punished?”

Baldwin’s and Clark’s cases raised not just levity but also significant questions about freedoms of speech and press. One resulting essay on the Sedition Act, in Newark’s Republican newspaper, noted that “all who can read, must know, that Congress is expressly forbidden by the constitution to form any law restricting the freedom of speech or the liberty of the press, and consequently, that they have no more right to enact that law, than the great Mogul would have, and it is no more obligatory on the citizens of the United States than an act of the British Parliament.” Another essay said that Baldwin’s “arrest proves how little confidence is to be reposed in the limitations of the law”—instead the Sedition Act showed “arbitrary power” as in “the days of Harry the Eighth.”

Excerpt adapted from Criminal Dissent: Prosecutions Under the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 by Wendell Bird, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2020 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.