Louisa Lee Schuyler and Virginia Gildersleeve, c. 1915. Photograph by Bain News Service. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Most graduation advice—whether given in boom times or moments of crisis—depicts a future replete with untrammeled ground and endless unknowns. And if you take a look at commencement addresses from the past, you’ll see a glimpse of what people in power told privileged young people to believe in and sketches of what the future could be, which we can now consider next to the reality of what came next. Lapham’s Quarterly is revisiting the history of giving advice to graduates and others in the process of acquiring knowledge or skills. Below is a selection from the first commencement address by a woman at Smith College in 1919.

You can celebrate a graduate in your life by introducing them to Lapham’s Quarterly. It’s an invaluable resource for graduates beginning a lifetime of learning outside the classroom. Send a gift subscription today for just $49.

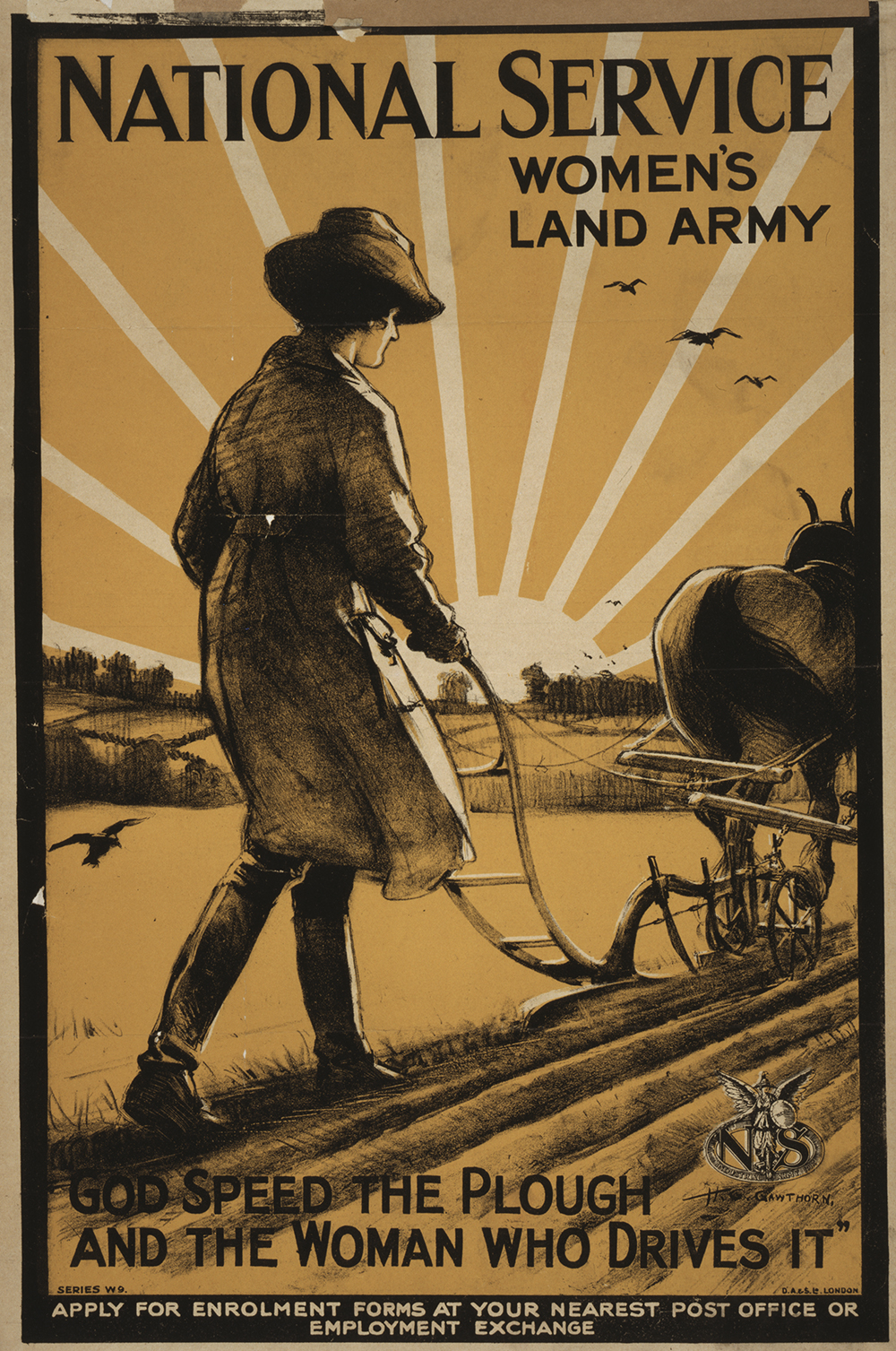

Smith College, a liberal arts college for women in Massachusetts, opened in 1871. Nearly fifty years later, the school chose its first female commencement speaker: Virginia Gildersleeve, the dean of Barnard College in New York, from which she had graduated herself before earning a PhD from Columbia University, where she studied with William Allan Neilson, president of Smith from 1917 to 1939. Gildersleeve had been active in making her students part of the war effort—sending students upstate to labor on farms and attend lectures in Women’s Land Army training programs—as one prong in her lifelong campaign for increased investment in women’s education. Her Smith College address made a patriotic—and classist—argument for sending women to college, even or especially in wartime, almost as a national security imperative.

The end of her speech extends beyond America’s borders toward international cooperation, a coda likely influenced by Gildersleeve’s activities in 1918. In the final year of World War I, the dean met Caroline Spurgeon, an English professor and literary critic, and Rose Sidgwick, a history lecturer at the University of Birmingham; together the two Brits and the American came up with the idea of a sort of League of Nations of women academics, so that, Spurgeon argued, “we at least shall have done all we can to prevent another such catastrophe.” Sidgwick never made it back to England, dying of the Spanish flu in December 1918 in New York. “As was so often the case in that epidemic of 1918, it was the younger and the stronger woman who died,” Gildersleeve wrote in her 1954 memoir. “I felt that she had died as truly in the service of her country as had the thousands of her young countrymen who had fallen on the fields of Flanders and of France.” A few months after Sidgwick’s death, Gildersleeve and Spurgeon founded the International Federation of University Women.

Nothing could possibly sustain me under this fearful responsibility of being the first woman to speak at a Smith commencement except the realization that your president himself is partly responsible for my education. He knows the worst, and if I disgrace his training, on his head will it be.

This is in many ways a blessed commencement season. For the first time in many years we can send out our graduates—we of the colleges—with a light heart. For the first time since the Class of 1914 went out, all unconscious of the fearful significance which future ages were to attach to its class numerals, we send our graduates out into a world comparatively, at least, at peace. The Class of 1919 is to be congratulated, I think, warmly congratulated, on the era in which its college life has fallen. You have passed your college career during some of the most critical years of the Great War: years which have seen the entrance of our own country into the conflict, victory coming to our arms, and finally, the dawn of peace. What a wonderful experience! Never will you forget these great days during which you have lived and worked together.

As the title of my commencement address, I have chosen the phrase “Ordeal by Fire.” My subject is one about which you have already heard a great deal, I am sure, but which you could hardly hope to escape at this commencement season—that is, the test which the war brought to our women’s colleges, the way we stood the test, and what we have learned from it. This test came at an opportune moment. The colleges of liberal education were already under fire. A battle was raging between the advocates of liberal education and of technical or vocational training. Women’s colleges, especially those of us here in the East, were accused of being obsolete and old fogyish and unpractical. Now personally, I have never thought that the issue between vocational and liberal education was so sharply cut. I have felt quite certain that we all needed both of these—we needed general, all-around training to make us better human beings, and we needed training in the particular handicraft or vocation or profession with which we were to earn our livelihood—to render some service to the world in return for our living. But at all events, when the war came, there was a chance for us to get some light on the problem as to whether this liberal education of the women’s colleges did make us better all-around human beings. And as the colleges appeared in the light of war, did they seem old fogyish, unpractical, obsolete? I do not think they did. They seemed far from perfect; we perceived ways, many ways, in which we might have been better; but on the whole, we seemed to be of use.

We had, at all events, not so trained our graduates that they were unconscious of the call of service and patriotism, because, as you all know, college women flocked by the thousands into the service of the government—flocked into a thousand different varieties and types of work of which they had never dreamed before the call to war came. In all these many types of new and strange work, the women college graduates showed certain traits for which we like to think a college education at least partly responsible. They showed brains to an appreciable extent! We hoped we had some brains, and we were glad to see evidence that the power of straight thinking in almost any line of work, from hoeing corn to drawing up State Department documents, was useful and practical. They showed one thing which a few years ago—well, not a few years, but perhaps even twenty years ago—might have seemed more surprising: they showed great physical strength, health, and endurance. I think that the work of the Woman’s Land Army and of other similar enterprises must have annihilated finally the last relics of that “clinging vine,” “fainting female” idea of mid-Victorian times, and it annihilated also any relics of the idea that a college education wrecked the health of a girl.

They showed also very strikingly the power of adaptability. That is a very important quality, which we had hoped college graduates might have. Even in normal times, you see, it is almost impossible in a woman’s education—far more difficult than it is in a man’s—to train her for the specific thing that she may hereafter be doing in life: some specific, technical job. We cannot foresee surely what her work is to be. And the jobs that developed during the war were of the sort that no human being could have anticipated. Who would have thought of training girls in college to inspect gas masks, for example? And yet that turned out at one moment to be an important form of service. At Barnard College we conducted for some months a training school for the YMCA overseas women workers, and we graduated 1,998 from an intensive one week’s training course during which they learned French, hygiene, recent history, geography—oh, much more than that—the manners and customs of our Allies, British, French, and Italian; canteen cookery; storytelling; recreational games; and physical culture!

War was not only a training school, it was also a trying-out ground—that is, metaphorically speaking, we jumped them over hurdles so that we could observe their reactions and see how they would be likely to react overseas. It was very interesting to see how well, on the whole, college graduates adapted themselves to this queer performance. I don’t, of course, mean that all college graduates were better than all non–college graduates, but they averaged much better in catching on quickly, in good temper under these strange and trying proceedings, and in learning these new tasks that were so suddenly imposed upon them.

I think another thing we all learned during the war about college graduates and other people was the truth of William James’ theory, expressed in his essay called “The Energies of Men,” where he tells us that we generally use so small a fraction of the powers at our command. We dawdle through life in a sort of half-awake manner; we could do so much more if the pressure came. The pressure did come, and under that tremendous stimulus many of us did a thousand times more than we had ever thought we were capable of. That lesson, I think, we should hold through our lives: that realization that if we only care enough, if the great call comes, there is more power within us than we have dreamed of.

Another thing that the war showed us was the value of scholarly research. Now it is not the primary purpose of the college to produce scholars. Of course the world at large has a strange superstition that any woman college graduate is a paragon of scholarship. You know—I know—that that is not true! Students in college should, however, appreciate the value of scholarship and of creative research. We were shown striking examples of this during the war—unexpected to some extent. We might have expected, of course, that a great physicist would discover some method of detecting the presence of a submarine. No one would reject physical research as unpractical. But take the archaeologist. Could anything have seemed more useless to the practical mind than archaeology, especially than the work of one scholar I know who spent many years happily as curator of ancient art and medieval arms and armor at the Metropolitan Museum in New York? Now if that appeals to you as it does to me, it seems a delightful way to spend one’s years, but useful? It is incredible to think that it could have been. But the world changes from time to time, and old customs return. And when the government needed trench helmets, it sent for the curator of arms and armor of the Metropolitan Museum, and he was transformed into a major in the Ordnance Department. He developed a very superior variety of trench helmet, which was of immense service to us in helping to win the war. I could give you other examples of the same sort of thing. We learned, then, that scholarly research may be useful. That is a good argument to use with the general public, but it shouldn’t be a necessary argument to use with a college audience. We ought to know that you never can tell whether it is going to be of use, and that whether it is ever going to be of any practical use or not does not really matter, because the mere pursuit of truth, the widening of the boundaries of human knowledge, is worthwhile just for its own sake.

Another change that came to us out of the war was a new attitude toward other nations. I heard a very charming and talented woman from Chile speak a few months ago and give her impressions of our country. She had visited the United States in 1911 and stayed here for a year, and she said politely that we were a very charming and delightful people at that time, but so concerned in our own affairs, almost unconscious of the existence of other nations, so occupied were we with the aims, interests, and activities within our own great boundaries. “And now,” she said, “I have returned to you in 1918, and had I known nothing of the history of the world during the last four years, had I been a visitor from another planet, I should yet have realized that some great thing had happened. Now your mind is full of the other peoples, you are thinking always of how to help them, you are the friend of all the world—the friend of all the world!” I thought that a very striking description of the change which has indeed come over the minds of so many of us. The colleges, I think, have been very quick to respond to this new feeling toward other nations, this new sense of responsibility as citizens of the world. It has been said that the intellectual class of the East was largely responsible for the entrance of America into the war—that is, for the development of public opinion here which resulted in our entrance into the war. Whether that was true or not, I think that the women and the men of the colleges did realize more quickly, perhaps, than some classes in the community our responsibility to other peoples in this great crisis.

We realize now, I think, the desires of the peoples of the world for closer cooperation, closer friendship, hard though it may be for politicians to devise the actual political machinery to put these desires into effect. Even the senior senator from this great commonwealth [Henry Cabot Lodge] may still indulge at times in the good old American pastime of “twisting the British lion’s tail,” but we nonpolitical thinking people realize very acutely that on the right sort of understanding and friendship between the great English-speaking peoples rests more than on any other single thing the hope of the world today.

Now how can we of the women’s colleges in these next critical years help to give effect to this yearning of the peoples for understanding and for cooperation? We can help, of course, in the first place by striving to get acquainted with the women of other countries, the university women of other lands who are reaching out their hands to us across the sea. By some such inspiring organization, by the exchange of the right sort of women professors, women instructors, and students between the institutions of the various countries, we can hope to learn to know the women of other lands.

But it won’t help us to get to know them unless we drop that strange provincialism with which we, like other peoples, are still afflicted. We must learn to realize that people can be different from ourselves and yet no worse than ourselves—in fact, perhaps better.

You remember how hard it was for the British and American soldiers to get over their amazement at that purely superficial habit of the French soldiers of kissing each other occasionally on the cheek. How hard it was for them to realize that a French general kissing a soldier on the cheek might exemplify the most superb and dauntless heroism of the war! If we exchange women professors and women students, and if you stand off and say, “Oh, but her clothes!”—“Have you noticed her strange manners?”—if you stand off like that, then this mutual understanding and cooperation won’t prove effective. We must forget the superficial differences and get at the real fundamental similarities.

The statesmen at Paris are now trying to construct, in the face of immense difficulties, a political machine to give effect to this desire for cooperation among the peoples. But there is something even more important—that is, a great web of friendship and understanding and good feeling among the peoples of the earth without which no political machine can work. Now we must help to weave that web, and each individual friendship between persons of different nations is just one more thread in that great web, one more safeguard against future international misunderstanding and perhaps enmity. And that is why this work, this interchange of knowledge and students, is so important, perhaps one of the most pressing duties that face the college and university women of America today.

As you go out today at this great moment, I give all good wishes. May your success and happiness be as great as the year whose name you bear! Good fortune go with you, 1919!

Read the other entries in our series: Lewis H. Lapham, Frederick Douglass, Kurt Vonnegut, Qohelet, and Quintilian.