Funeral for the last omnibus, 1913. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

On a chilly day in January 1913, a crowd of nearly a hundred thousand lined the streets of Paris for a somber funeral procession. A black, horse-drawn carriage, decorated with wreaths, passed through those assembled to pay homage to a cultural giant that had haunted the city for nearly a century.

There was no coffin on the carriage. The “funeral” was for the carriage itself: a bulky contraption capable of holding more than thirty passengers on two decks. Since the 1820s horse-drawn carriages like this one had been the backbone of public transit in Paris and other cities around the world. Now they were functionally dead, their horsepower replaced by newer forms of transit fueled by electricity or petroleum. Parisians felt bittersweet, however, about the departure of their beloved “omnibus,” whose technological eclipse seemed to take with it much of what had made Paris so special.

Today the humble bus is the workhorse of public transit, in the nineteenth century it was a novelty. Literary scholar Masha Belenky dubbed it an “engine of modernity” in her new book of the same name, which chronicles the cultural sensation that the omnibus was for nearly a century after its debut: the star of page and stage, and a symbol of the dramatic social and economic changes transforming Paris and France in the nineteenth century.

As Belenky writes, the omnibus—from which our modern word bus derives—debuted in Paris in April 1828, two years after an entrepreneur from Nantes named Stanislas Baudry tested the transport in the streets of his hometown. Baudry was originally just trying to help customers get to the bathhouse he owned on the outskirts of Nantes, but he discovered his coach rides were a sensation even for those who weren’t going to the bathhouse. After this success, Paris was the obvious next step.

Before Baudry debuted his omnibus, Parisians could walk around their city or hire a private coach for 1.25 or 1.50 francs—out of reach for a typical Parisian laborer, who typically earned less than three francs per day. But with the city nearly doubling in size from 1800 to 1846, there was a pressing need for better ways to get around.

A ride in one of the new Parisian omnibus’ fourteen to sixteen seats cost just twenty-five centimes in 1828, one-fifth the cost of hiring a private coach. That meant, as Belenky notes in her book, middle- and working-class Parisians could now affordably traverse the city—or at least certain fixed routes—protected from the elements above and the filthy sewage-strewn streets below. Within months, competing omnibus lines had sprung up in Paris; by 1829, the innovation had spread to London, and by 1830 it had crossed the Atlantic to New York City.

The origin of the contraption’s unusual name remains unclear. The standard story is that the name omnibus, which means “for everybody” in Latin, had adorned a hat shop by Baudry’s first station. He was charmed by the name, the legend goes, and adopted it for his vehicle, which—unlike the more expensive private coaches already available for hire—was for everyone. Regardless of the veracity of this origin story, the name quickly stuck, even after Baudry’s death in 1830 amid floundering business.

Something about the omnibus, open for everyone—if for a small fee—seemed to fit the spirit of the nineteenth century. The idea of affordable mass transit had been tried 150 years prior, when the polymath Blaise Pascal had established a public transportation system for Paris dubbed the carrosse à cinq sols, a four-horse carriage accommodating up to eight passengers and two staff. The carrosse provided inexpensive rides on five Parisian routes for men and women, rich and poor. But Pascal’s idea had foundered on the intense class divisions of the ancien régime: wealthy riders, upset at having to share rides with the rabble, would simply buy all the seats in the carrosse for themselves. Eventually the rich got the government to ban lower-class riders entirely. That, Belenky writes, put an end to the wild popularity of the carrosses. But by the 1820s French society was more ready to mix classes on public transit. The omnibuses were obligated by law to accept all paying (and nondisruptive) customers, regardless of wealth or social status.

The omnibus’ affordability was a boon for working-class riders. But the nineteenth-century omnibus attracted riders of all social ranks—even the very highest. A French princess, the duchesse de Berry Marie-Caroline, was widely believed to have ridden an omnibus incognito, as part of a ten-thousand-franc bet (for charity) with her father-in-law King Charles X. Whether or not this happened, her association with omnibuses helped popularize them, and one line of them was named the Carolines.

A few years later, when a revolution overthrew Charles in favor of his cousin Louis-Philippe, the new king’s family was trapped on the outskirts of a Paris still strewn with barricades and revolutionaries after three days of street fighting. Told it was imperative they join Louis-Philippe at once, his wife, children, and sister did the most sensible thing they could think of to traverse Paris: they took an omnibus. “It is,” historian Munro Price writes, “one of the few recorded occasions on which a victorious revolutionary leader’s family have rejoined him by public transport.”

By 1829, just a year after Baudry launched his first line, there were ten new companies running 264 omnibuses in Paris. Each omnibus could transport 300 passengers per day, for a total of nearly 80,000 daily rides in a city of 700,000 inhabitants.

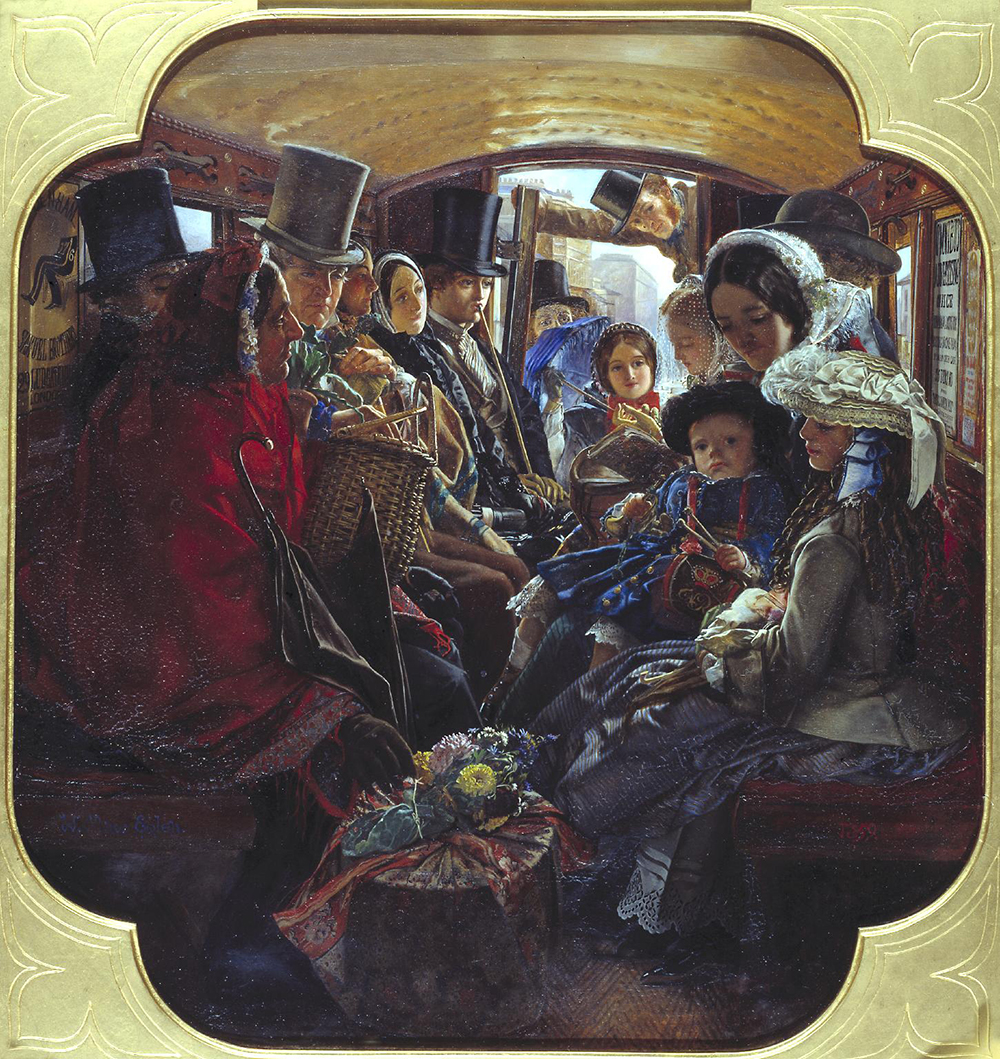

Depictions of omnibus passengers in nineteenth-century literature and art were abundant, as Belenky chronicles in her survey, and they portrayed a mélange of rich and poor. Within a month of the omnibus’ debut, a vaudeville play that featured the devices was performed for audiences, with a plot involving private carriage drivers upset about their newfound competition. Before long, a whole host of omnibus-themed literature had sprung up, from guidebooks to Paris framed around sights to be seen from the city’s omnibus lines to the climax of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, where his 1832 revolutionaries build their doomed barricade in part by commandeering “an omnibus drawn by two white horses” and, after expelling the passengers and driver, overturning it in the street.

The omnibus also spawned a sort of literary subgenre of its own, what Belenky calls the “omnibus flaneur,” a (male) wanderer who takes in the city’s near-infinite variety by riding an omnibus and observing its passengers and the city beyond. Belenky found abundant uses of the omnibus as a literary trope in a range of works from novels to short stories to guidebooks to plays, which are relayed in Engine of Modernity: The Omnibus and Urban Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris.

“By rubbing shoulders with all these lives that came from all corners of the world in order to meet at this banal junction, I always feel like I am surrounded by closed books, the covers of which I wish to lift,” wrote author Lucien Griveau in 1883 of navigating Paris by omnibus. The bibliophile Octave Uzanne noted that on an omnibus, “artists find varied facial expressions, attitudes, details of movements, colors of fashionable clothing; novelists discover numerous real-life types upon which they model their heroines; for there are few other places where observing people is easier and less indiscreet.”

The omnibus fascinated authors in part because it was a useful literary structure: an author could write a series of vignettes, each beginning when a passenger boards the omnibus and ending when that passenger debarks. But the omnibuses also seemed to be a metaphor for the emerging industrial and slowly democratizing society of the nineteenth century.

“There is no doubt that the omnibus is the agent of democratic progress,” wrote journalist Taxile Delord in an 1854 compilation of omnibus-themed stories, jokes, and facts called Paris-en-omnibus. “The omnibus diminishes distances, combines all social classes, mixes up all the ranks.” Chronicler Emmeline Raymond noted in an 1862 article that at omnibus stations, seats were allocated strictly based on passengers’ place in line, rather than by social standing—a fact that would have horrified the aristocrats who brought down Pascal’s seventeenth-century attempt at mass transit.

Poet Charles Soullier put his praise into verse in 1863:

The professions and ranks are mixed there all together

The stout shopkeeper is next to a worker

The priest’s frock mingles with military uniform;

You see here united in all liberty.

Of course, these tales of social mixing only went so far, as Belenky discusses in chapters devoted to the omnibus’ interaction with class and gender The role of omnibuses as space open to all caused repeated tension with nineteenth-century gender norms. When omnibus capacity was expanded by the addition of rooftop seating in the 1850s, the second deck was originally reserved for men only—a limitation only partly explained by the voluminous hoop skirts then in fashion. Even inside the omnibus cab, nineteenth-century moralizers saw the mixing of genders as vaguely scandalous, something to be avoided if possible and constrained if not. One midcentury article unearthed by Belenky told women riding omnibuses to “avoid all conversation and limit interaction as much as possible, if you must have it at all,” for fear that “a certain eagerness on your part may be misinterpreted.”

Some of the nineteenth-century observations about gender dynamics on omnibuses Belenky uncovered in her research echo twenty-first-century critiques of public-transit behavior. Raymond warned of the nineteenth-century manspreader, “who tries to get comfortable without regard to his neighbors...he leans over, he stretches out, he sticks out his elbows, etc.” Twenty years earlier, author Édouard Gourdon wrote of sexual harassers being drawn to the new form of public transit: “le monsieur aux cheveux gris,” or the gray-haired man, who spends “five-sixths of his life” on the omnibus because he enjoyed the opportunity to bump up against attractive women in close quarters.

Beyond questions of gender, some observers found the social environment of an omnibus to be alienating rather than energizing, such as another author in the 1854 Paris-en-omnibus:

Nothing predisposes toward sadness and melancholy more than frequent omnibus travel. A regular omnibus rider, no matter what sex, is a somber, quiet person who turns inward. The omnibus makes you mistrustful and misanthropic...You’d think people would get to know each other. Ha! Think again: you sit next to one another without saying a word.

The omnibus also posed a physical danger to both its passengers and Paris’ pedestrians, as a massive vehicle lumbering down the capital’s narrow streets. The omnibuses posed a risk both to people in the path of the carriages—Émile Zola, for example, used a character getting run over by an omnibus as a plot point in his 1883 novel Au Bonheur des Dames—and to the riders themselves, especially those perched precariously on the exposed upper deck. Omnibus-related injuries or deaths were so prevalent that one whimsical author suggested that doctors must be major omnibus investors because injuries from the carriages gave them so much business.

The supposed democratic nature of the omnibus also had its limits. Belenky finds that the omnibus flaneur of literature, who recounted stories of his rides around Paris, was explicitly a character who rode the omnibus by choice, rather than by necessity. In one 1894 collection of omnibus stories, the flaneur makes a point of exiting the omnibus at the end of each story and taking a private cab back home.

While the low fare was within the reach of Paris’ working class, it was still too much for the city’s abundant poor. (Ridership increased dramatically in the 1850s when omnibuses added the second deck, exposed on the roof, which an additional fourteen passengers could ride for half price.) Service didn’t start until 8 am, a perfectly fine hour for middle-class Parisians but one that left many working Parisians to trudge to work on foot. And while omnibuses were theoretically open to all riders regardless of social status, conductors were allowed to reject passengers for “inappropriate attire” or the potential to “disturb” other passengers—limitations that fell predominantly on the poorest Parisians.

The reality of omnibus ridership probably involved much less class mixing than was depicted in books and artwork. “And yet,” Belenky writes, “more than any other aspect of the omnibus, it was the potential for class inclusiveness that captured the imagination of contemporary commentators.”

The fascination with omnibuses persisted even after the horse-drawn carriages were eclipsed by metros and motor buses in the early years of the twentieth century. While omnibuses had endured competition from trams and streetcars, these new motorized forms of mass transit proved fatal. Still, while these new methods of transit were faster and more reliable, many Parisians—or at least, many Parisian writers—felt that speed came at a cost. The slower pace of the omnibus was better for observing the city, such a key aspect of the omnibus’ cultural cachet; other early twentieth-century writers presciently worried that the faster motorized transit would prove more dangerous for pedestrians.

Even those who were happy to see technological progress recognized the significance of the departing omnibus. Even beyond its impacts on culture and mobility, the omnibus had helped reshape the geography of nineteenth-century cities. The hulking carriages challenged Paris’ many medieval streets, before Baron Haussmann’s famous reconstruction of the city. “In streets where in the olden days a priest’s mule or a gentleman’s horse squeezed between walls so narrow they almost touched, now let circulate the omnibus, this Leviathan of carriages, and other vehicles passing each other with lightning speed,” writer Théophile Gautier noted in 1854. A Paris of omnibuses demanded wider streets, and soon enough those wider streets arrived. And so it was that the last ride of a Parisian omnibus in January 1913 became a funereal occasion, passing with ceremony rather than a whimper.

In a sign of things to come, historian Peter Soppelsa notes that the omnibus’ funeral was sponsored by the car magazine L’Auto, and the horse-drawn carriage was followed in the procession by a column of automobiles; also present were a number of bicyclists. Most of the old horse-drawn omnibuses would within a few years be melted down to support France’s efforts in World War I. London’s last few horsebuses endured another year, until August 1914, when its horses were commandeered for the war.

Newspaper accounts of the event cast the omnibus as a “loyal servant” who had passed on after a “fulfilling career.” As for the last omnibus itself? As Soppelsa wrote, it was packed with “haggard old men” singing “a funeral march with a polka rhythm.” Hanging from its side was a sign bearing a horse’s face and the simple caption: merci.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece gave insufficient credit to the work of Masha Belenky, author of Engine of Modernity: The Omnibus and Urban Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris, as a source for the research of this piece.