Lady Macbeth, by Wilhelm Lehmbruck, 1918. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Bruno and Sadie Adriani, 1956.

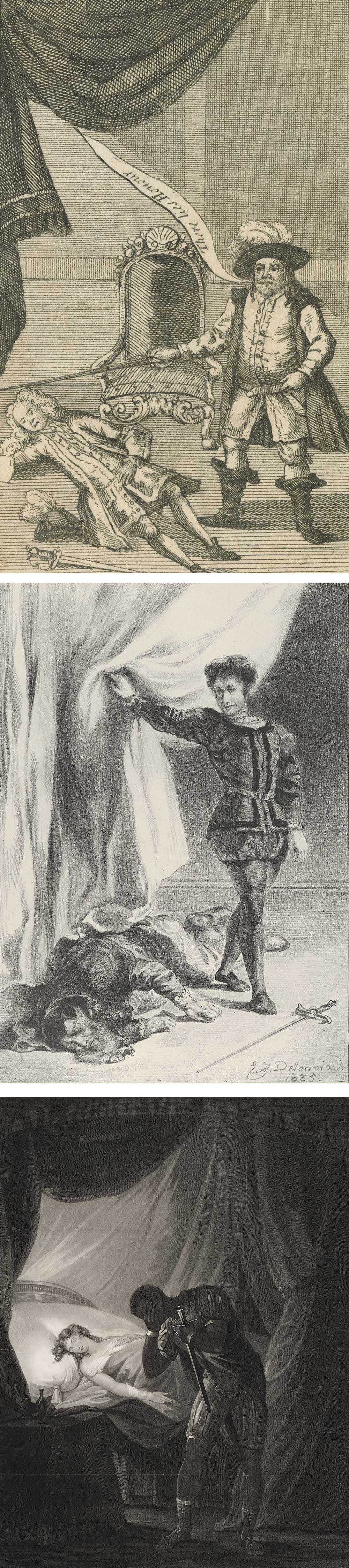

There are seventy-four onstage deaths in Shakespeare’s canonical plays, fourteen in Titus Andronicus alone. By the mid-eighteenth century, the corpse-clogged stage was such an obsolete cliché that Henry Fielding has his 1730 burlesque The Tragedy of Tragedies or Tom Thumb conclude with eight murders and a suicide in as many lines. Actor David Garrick omitted what he called “all the rubbish” from the last act of Hamlet, ostensibly to suit the taste of his time, but actually to allow himself a protracted death scene.

After the king’s death in Thomas Preston’s sixteenth-century morality play Cambises, three lords enter for the sole purpose of clearing away his corpse. As bodies proliferated in plays, the actors had to be efficient in removing inert carcasses from the stage and with more justification from the playwright than the three lords had. Hamlet is exceptionally helpful when he informs his mother, regarding the slain Polonius, “Ile lugge the Guts into the Neighbor roome.” By the nineteenth century this line was usually cut, and the scene ended with the exits of Hamlet and his mother at separate ends of the stage. In an age when the curtain descended or closed as a scene concluded, the disposal of Polonius was of less concern.

The drama critic Percy Fitzgerald, in his nineteenth-century survey of Shakespearean production, refused to dismiss the dragging away of Polonius as a “flighty, capricious proceeding.”

The incident is most potent, and influences all that follows, and that the unhappy prince was now filled with the idea of completely hiding his bloody act by the process of hiding away the body—“safely stowed,” as he put it. We can imagine nothing more appalling than this moment.

Except, perhaps, in the next scene, when Hamlet callously remarks on the smell emanating from this banquet for worms. Still, Fitzgerald had a point. After postponing the murder of Claudius, Hamlet’s precipitous dispatch of Polonius and his subsequent behavior bespeak a new, more ruthless turn of mind. Many actors shrank from this aspect of the prince’s psychology. Victorian actor Henry Irving dared to be seen “dragging the body of Polonius from behind the arras” in 1874, but in later productions, after he had become a prominent actor-manager, he was content to view the body by candlelight.

This convention of disposing of the dead inspired in-jokes. In John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi, there is a moment of black comedy when Bosola, who has murdered the Duchess and carried her corpse off stage in Act IV, has to do the same for the Cardinal’s mistress Julia in the next act. When the Cardinal orders him to “Take up the body,” he comments:

I think I shall

Shortly grow the common bier for churchyards.

Perhaps the most ingenious of these removals occurs at the end of Henry IV, Part I (act 5, scene 4), when Falstaff comes upon the slain body of Hotspur and decides to claim the trophy as his own. The First Folio stage direction reads Stabs Hotspurre and takes him on his backe, and a few lines later Throws down the bodie at the feet of Prince Hal. This requires a certain agility and stamina on the part of the actor playing the fat knight.

In the eighteenth century, according to Fitzgerald,

[James] Quin had little or no difficulty in perching Garrick upon his shoulders, who looked like a dwarf on the back of a giant. But oh! How he tugged and toiled to raise Barry from the ground…At length this upper-gallery merriment was done away with by the difficulties which Henderson encountered in getting Smith on his shoulders. So much time was consumed in this pick-a-back business that the spectators grew tired, or rather disgusted. It was thought best, for the future, that some of Falstaff’s ragamuffins should bear off the dead body.

Although a few actors were capable of hoisting the dead warrior, later acting editions often prescribe soldiers to perform the task. In 1945 Laurence Olivier as Hotspur added to his displays of athletic death by persuading Ralph Richardson’s Falstaff to carry him upside down in full armor, his legs over the fat knight’s shoulders.

Corpse clearance in the post-Brechtian theater provokes no embarrassment. In Michael Boyd’s 2000 staging of the Henry VI trilogy at the Swan Theatre, he invented a red-clad, mute character called the Keeper who brought each corpse to its feet and walked it off.

Not only deaths but scenes of torture, eye-gouging, and amputations were frequent on the pre-Commonwealth English stage. An audience familiar with domestic deathbeds, public executions, and moribund plague victims left in the open would have been discriminating spectators. If the Romans of the Empire channeled capital punishment into mass entertainment in the arena, the princes and potentates of Christendom turned a judicial event into a public spectacle. Beheading, hanging, drawing and quartering, burning, drowning, garroting, flaying, whipping, breaking on the wheel, and lopping off limbs, tongue, and ears were all on display for a demanding crowd of enthusiasts.

As at a sporting event, the mob might boo a headsman off his stroke or cheer as the disjecta membra of a disembowelment were held up to view. The victim’s behavior was also under scrutiny: fortitude or bravado might win admiration, while flinching or struggling met with derision. A forthright speech of contrition and resignation was always welcome. Although the more gruesome of these punishments were eventually suppressed, the noose and the guillotine remained popular diversions until the end of the nineteenth century.

The theater historian W.J. Lawrence devotes a good deal of erudition to describing how shows of mayhem were achieved, with bladders and sponges of cow’s blood and vinegar, the liver and lights of a slaughtered sheep, fake heads with their gory reservoirs. In George Peele’s 1594 play The Battle of Alcazar, for instance, in which three characters are disemboweled on stage, “violls of blood and a sheeps gather” are called for as props. Lawrence does not conjecture on how stage hangings were achieved, but it is a relatively simple affair. A Saint Louis University production of Caryl Churchill’s 1976 play Vinegar Tom, available on YouTube, graphically shows two witches being hanged; once the stools are kicked out from under them, their bodies twitch in the air. The murky lighting no doubt conceals the harnesses that make this possible.

The Elizabethan theater proprietor Philip Henslowe’s diary lists expenses for an executioner’s scaffold (“frame for the heading”) in Black Jone (i.e., John, 1598) and later for George Chapman’s Conspiracie and Tragedy of Charles, Duke of Byron (1608). As scholar Glynne Wickham has pointed out, the purchase and storage for the scaffold frames speaks to the crucial nature of these execution scenes. The first recorded stage decapitation, that of Isabella in John Marston’s The Insatiate Countess (1613), may have employed a conjurer’s trick known as “The Decollation of John Baptist.” The mechanics had been laid out in Reginald Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft (1592) with suggestions on how to make the effect appear more grisly. In the “ripped from the headlines” drama A Warning for Fair Women (1599), John Beane is stabbed fifteen times, so that “he spends more breath that issues through his wounds / then through his lippes” (act 4, scene 5); put in contact with his attacker, the wounds bleed again, allowing him to identify his murderer before he expires.

The impulse to create cheap thrills is timeless, and some modern stagings luxuriate in such tricks. The all-male Propeller Theatre set its 2011 Richard III in a horror-movie psycho ward whose denizens’ access to edged tools led to the white coats becoming crimson long before the intermission. During the Henry VI, Part II seen at the Swan in 2000, the reviewer for the London Daily Express reported “blood from a severed arm sprayed over my lap. A human liver slopped to the floor by my feet. An eyeball scudded past, then a tongue.” For an audience inured to “splatter flicks,” such overly graphic effects can have diminishing returns for everyone but the dry cleaner.

Lawrence lists the various actions characters go through as they prepare for execution or self-mutilation, but he provides no evidence as to how the actors, deft enough at the mechanics of simulated bloodletting, played the victim during these episodes. Shakespeare and his colleagues may have imitated the atrocities of Senecan tragedy, but their characters rarely espoused Seneca’s philosophical attitude to death. Only the most stalwart of heroes faces it with equanimity, let alone contentment. The moment of death became of sufficient dramatic weight that its prominence needed to be supported by spectacle. It points to what may be a decisive factor in the proliferation of death scenes in Elizabethan and Jacobean drama: the emergence of the professional actor seeking opportunities to demonstrate his virtuosity. Death provides the moment when the star could round off his performance with a stirring speech in full view of the entire audience.

With dying a dramatic attraction, the valedictory speech takes center stage. The plain statements of debility, demise, and contrition found in medieval drama metastasize into rhetorical showpieces. Shakespeare, for the most part, bucks this trend. Of Shakespeare’s protagonists, only Romeo indulges in a protracted and florid farewell, appropriate for a poetic lover. More usually, Shakespeare prefers to let the moment of death occur without a wordy accompaniment: such prominent characters as Macbeth, Lady Macbeth, Falstaff, Cordelia, Hector, Henry IV, and Richard III die unseen; Titus and Coriolanus depart unvoiced. Juliet declares, “Then I’ll be brief” before stabbing herself. Caesar utters only the sardonic Et tu, Brute, echoed when Brutus declares before his suicide, “Caesar, now be still. / I kill’d not thee with half so good a will.” Hamlet’s last words concern the political succession before a slow fade into Horatio’s “the rest is silence.”

Presumably Hamlet had more to say, but Shakespeare prefers to pinpoint death’s arrival verbally as a simple exclamation or interruption: Lear’s “Look there, look there!”; Othello’s “Killing myself, to die upon a kiss”; Antony’s “I can no more” (he dies in the course of Cleopatra’s next speech); and Cleopatra’s own “What should I stay—.” The ellipsis serves as the signal for extinction. The soul expires on the breath.

One of the most extended death scenes in Shakespeare is the stifling of Desdemona by Othello. Implored by Emilia to “speake againe,” she recovers just enough to affirm her innocence—“A guiltlesse death, I dye!”—and to forgive her erring husband: “Commend me to my kinde Lord: oh farewell.” Unlike an exemplary Christian but like a compliant spouse, she commends herself not to the Lord but to her lord and master. Henry Jackson, a young scholar soon to be a fellow of Corpus Christi, left a Latin record of seeing Othello at Oxford in September 1610. He was especially struck by the dying moments of Desdemona, who “pleaded her case very well” and “moved [us] more after she was murdered, when lying on the bed she appealed to the spectators’ pity with her very expression.” Jackson’s notation is pregnant in suggesting, first, how the audience’s attention could be riveted on a stage death; then, that a boy actor might move it by skilled mimicry; and, last, that the action of dying was drawn out. Attending a Royal Shakespeare Company Othello recently, a critic records that “the affective power of her slow death here was…remarkable.” Desdemona enacts dying both in extenso and in extremis.

Rhetorical reticence makes Shakespeare an outlier. Most of his contemporaries have their dying heroes spout magniloquent tirades. In scenes of judicial execution, the condemned usually puts up a show of defiance or stubbornness before uttering a repentant “scaffold speech.” This reassures the audience that murder will out in a world ruled by Providence.

Excerpted from The Final Curtain: The Art of Dying on Stage by Laurence Senelick, published by Anthem Press. Copyright © 2022 by Laurence Senelick. All rights reserved.