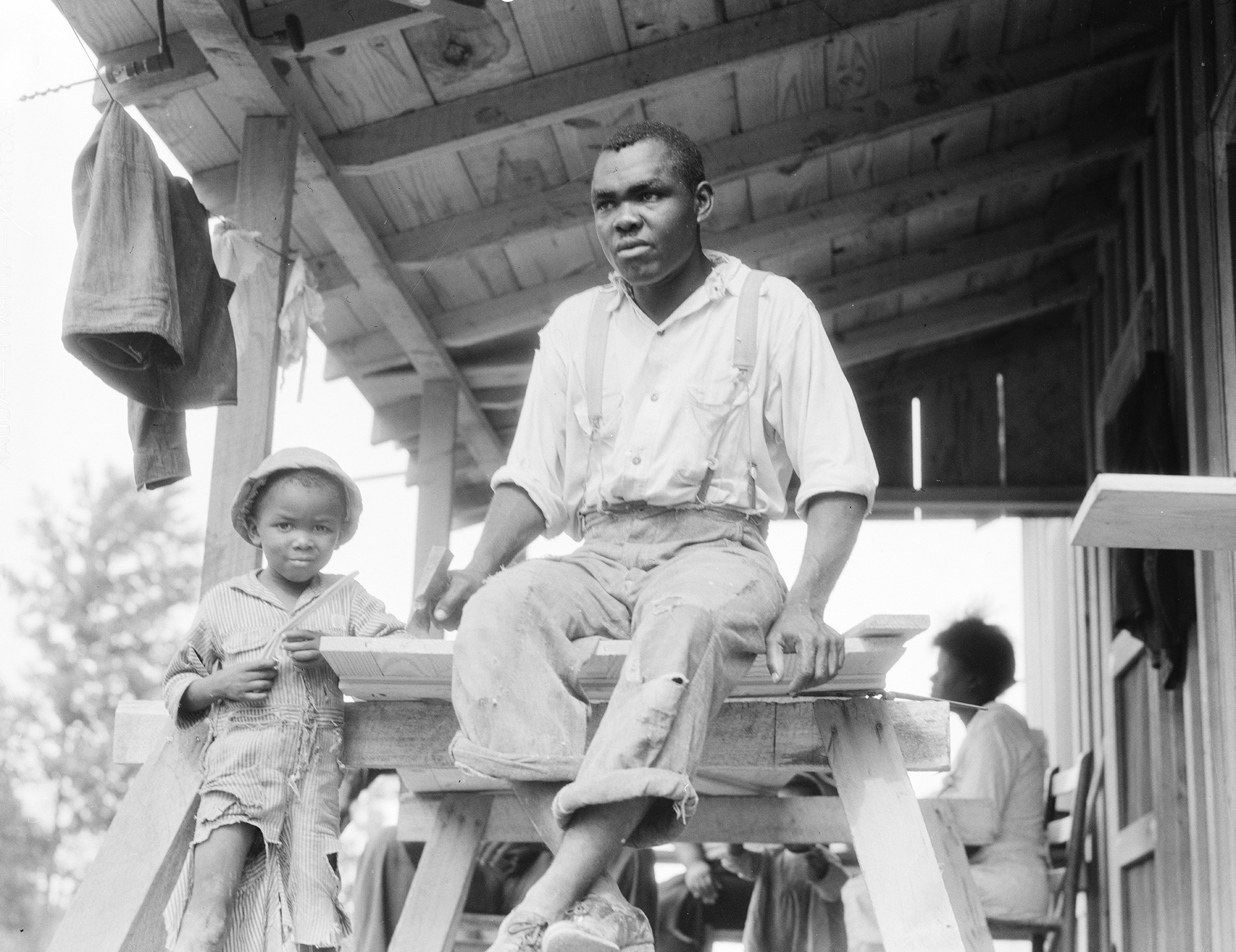

One of the more active members of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, an evicted sharecropper now building his new home at Hill House, Mississippi, 1936. Photograph by Dorothea Lange. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

On the evening of July 16, 1931, 150 Black sharecroppers turned organizers met at a church outside of Dadeville, Alabama, to plan their support for the Scottsboro Boys, nine Black teenagers who were falsely accused of raping two white women. An informant tipped off Tallapoosa County sheriff J. Kyle Young about the meeting, but when he and his posse went to break it up, they were stopped by sharecropper Ralph Gray, who stood guard outside the building. In the argument that ensued, Young shot Gray, who shot back. Both men survived—until Gray was found at his home in nearby Camp Hill by a white mob deputized by Matt Wilson, the town’s police chief. The mob killed Gray and five other croppers, and severely beat at least two women: Gray’s wife, Jane, and Estelle Milner, a Black teacher who had been branded an agitator. As historian Mary Stanton writes in Red, Black, White: The Alabama Communist Party, 1930–1950: “Gray’s body was dumped on the Tallapoosa County Courthouse steps in Dadeville and used for target practice—a lesson to would-be organizers.” Despite ample news coverage, there were no state or federal investigations into the Camp Hill Massacre, as it came to be called.

Rather than being cowed, fifty-five Black sharecroppers formed the Alabama Share Croppers’ Union (ASCU) less than a month after the Camp Hill Massacre. At a time when few other organizations would defend African Americans, labor unions like the ASCU fought for both better working conditions and civil rights, as in its defense of the Scottsboro Boys. In the process, Black unions not only continued the fight left unfinished following Emancipation but also laid the groundwork for the civil rights movement. Their various manifestations and efforts on behalf of Black workers demonstrate the diversity of tactics employed in the struggle for equality.

After the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, white lawmakers and justices worked quickly to limit the advances and rights promised by these additions to the U.S. Constitution and were especially focused on constraining the rights of Black workers. As Eric Arnesen writes in Brotherhoods of Color: Black Railroad Workers and the Struggle for Equality, the South remained reliant on Black labor even after the Civil War, but because the region could no longer obtain that labor through enslavement, it turned to other coercive—though legal—means, such as convict labor. Georgia introduced the convict-lease system in 1866, arresting Black men on pretenses such as vagrancy, then leasing them out for manual labor, often to railroads.

Where convict labor could not be obtained, employers turned to another kind of bondage imposed on Black workers: sharecropping. The Freedmen’s Bureau, established by the federal government in 1865, shortly before Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, was ostensibly tasked with supporting newly freed African Americans but kept them in cotton production instead of opening opportunities in other industries. Without the means to obtain self-subsistence, many of the formerly enslaved were forced to work the lands of white planters in exchange for a share of the annual crop. Tallied against their shares were the planters’ purported expenses for the croppers’ housing, food, clothing, tools, etc., which were provided at exorbitant rates to ensure croppers were always in the debt of planters. In this arrangement, planters also controlled whether croppers could work for other employers, such as the railroads, whose agents had to solicit planters for the labor of “their” croppers. And when Black workers attempted to become self-sufficient, they could always be massacred, as happened in Leflore County, Mississippi, in 1889, when dozens of Black residents were killed by the National Guard after they tried to join a cooperative for agricultural supplies.

Southern states overwhelmingly targeted African Americans to become convict laborers and sharecroppers. The case of Joseph Callas, a Russian Jew who was forced into a convict-labor camp in Arkansas in 1908, illustrates how anyone could be picked up for vagrancy, but—as Callas later related in an article for Collier’s—Black workers outnumbered white workers more than two to one and faced especially cruel treatment, such as wanton beatings from overseers. Similarly, African Americans comprised more than 95 percent of croppers on cotton plantations in the Mississippi Delta in 1913, reflecting the failures of Emancipation.

Nowhere were these unfulfilled promises as glaring as in the Mississippi Delta. Stretching along the Mississippi River from the southeast corner of Missouri down through Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana to the Gulf of Mexico, the Delta was home to horrifying conditions. In American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta, Nan Elizabeth Woodruff compares Delta planters to their counterparts in Belgian Congo, where the colonial forces of King Leopold II enslaved, mutilated, raped, and murdered the Congolese: “They may not have cut off the heads and hands of their African American workers, but they engaged in peonage, murder, theft, and other forms of terror to retain their labor.”

Amid the menace of convict leasing, sharecropping, and general white-supremacist violence, Black organizer Marcus Murphy helped form the Alabama Share Croppers’ Union. Hired by the Alabama Communist Party to organize sharecroppers and other farmworkers, Murphy—aware that overt organizing could spell death for Black workers—focused on building an underground resistance movement, divided into cadres of armed union members. Rather than meet en masse to discuss plans, each group was assigned a captain to coordinate their efforts. During Murphy’s tenure as leader of the ASCU, the union expanded from Alabama to Georgia and Louisiana.

The ASCU’s commitment to racial equality set it apart from the mainstream U.S. labor movement at the time. The movement had first coalesced nationally around the Knights of Labor, which was founded in 1869 and attempted to organize both Black and white workers in all industries, with a focus on the demand for an eight-hour workday. Facing accusations of political violence and consequent state repression, the Knights of Labor saw its membership start declining in 1886, when many local branches joined the newly formed, and more conservative, American Federation of Labor. The AFL came to dominate the U.S. labor movement and employed a double standard to exclude Black workers: it allowed its affiliated unions to bar African Americans while also refusing to charter Black-only unions. Not content to keep their racism within the confines of their own organization, AFL members also attacked other unions for their interracial organizing. In 1941 in Helena, Arkansas, as Woodruff relates in her book, a mob of fifty white AFL members beat, tarred, and feathered two organizers with the Congress of Industrial Organizations, which had been founded six years earlier as a more radical alternative to the AFL and included Black workers.

Black workers began organizing independently of the hostile mainstream labor movement, forming their own unaffiliated unions. The ASCU remained independent until 1937, when it merged with the CIO. The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU), which also organized sharecroppers, was founded in 1934, three years after the ASCU, and remained independent until 1946, when it joined an AFL inching toward desegregation after World War II. The AFL and the CIO would go on to merge in 1955. Full desegregation of the labor movement would arrive only with the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964.

Instead of drawing their support from the conservative AFL, the ASCU and STFU were founded by the Communist and Socialist Parties, respectively, which provided them with organizers, legal representation, funding, and other resources. Union members often could rely on only left-wing radicals; in its early years, following the Camp Hill Massacre, the ASCU counted on cash donations delivered by white communists, who risked their livelihoods, if not their lives, in the process.

The ASCU’s ten thousand members were mostly, but not exclusively, Black and stretched from Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama to Georgia and even North Carolina. The STFU had thirty-five thousand members, of which up to 15 percent were white, across Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Alabama. Of the unions’ Black members, nearly all were direct descendants of enslaved African Americans. The grandfather of Ralph Gray, for example, was emancipated after the Civil War.

Black unions waged two struggles simultaneously: one against exploitation by their employers, the other against racism throughout U.S. society. These issues always implicitly, and often explicitly, intersected. Black workers developed a strategy to address them together that was dubbed “civil rights unionism,” a form of labor organizing meant to achieve not only economic goals but also political ones.

While both the ASCU and STFU practiced civil rights unionism, it was the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) that best captured the synthesis of labor organizing and civil rights activism, as advocated by its president A. Philip Randolph. The union was founded in 1925 to organize twelve thousand mostly Black sleeping car attendants employed across the United States by the Pullman Company. BSCP members had to defend themselves from further segregation—being pushed out of working in the railroads altogether, rather than just being segregated from other railroad workers—as well as cooptation by the all-white Order of Sleeping Car Conductors, who sought to take over the BSCP once it proved successful at organizing workers. At the same time, the BSCP also had to win higher wages and other concessions from Pullman. Unlike the ASCU, the BSCP originated as an aboveground effort focused on urban transportation hubs, often in the North, where workers were more likely to be fired than killed for organizing. That said, railroads of course traversed the country, and BSCP members found themselves confronting the same racially hostile conditions that the ASCU and STFU faced. Unsurprisingly, northern BSCP members became personally invested in the fight against southern segregation, with Black train crews responding to racist behavior from white passengers or railroad workers by going on strike, then and there, until the matter was resolved.

The BSCP openly and consistently connected its labor organizing with more general issues of race. The BSCP’s official publication, Messenger, implored members to cast off the “slave psychology” formerly associated with portering, and the union’s annual convention brought workers together with reformers and politicians. Its leaders supported the creation of the National Negro Congress, a more militant alternative to the NAACP. It is largely thanks to the BSCP that labor organizing became an avenue for Black struggle, whereas many African Americans had previously seen it only as the purview of white workers—due in no small part to the AFL’s racial discrimination.

Unable to rely on the solidarity of white unions, Black unions such as the BSCP looked elsewhere for support. Besides the Communist and Socialist Parties, the greatest source of aid became progressives, who had gained political power in the federal government during the Great Depression. After seeing how the NAACP found success, Black unions understood that they had to focus on winning political support from the federal government, not the states. After Franklin D. Roosevelt won the 1932 presidential election, the New Deal opened up more avenues for the unions to pursue federal recognition. The New Deal not only allowed Black unions to become the legal representatives of Black workers but also created federal agencies tasked with assisting both unions and workers. One of them, the National Mediation Board, forced Pullman to negotiate with BSCP, and the porters won their first contract in 1937. Also that year the ASCU’s lobbying of the Roosevelt administration helped lead to the creation of the Farm Security Administration, which relocated croppers to land purchased by the federal government. The STFU worked with the FSA on a joint program finding croppers off-season work, picking crops in the Southwest. While the federal government often made the same racist decisions that organizers had been dealing with from other employers, the fact that the croppers were no longer beholden to the planter class was significant. These efforts didn’t just improve the working conditions of Black union members, they also offered workers opportunities to escape the bondage of convict leasing and sharecropping, whether by working in other industries, such as the railroads, or farming outside the South—even on their own land.

As groundbreaking as the ASCU, STFU, and BSCP could be, they were not without their faults, especially when it came to politics, gender, and even race. The competing influences of communists, socialists, and progressives over the unions, and the labor movement in general, caused conflict between radicals and moderates, such as when the “Popular Front” strategy of the late 1930s emphasized unity against fascism over racial equality and other goals. Prefiguring a problem that would go on to plague the civil rights movements, all three Black unions also elevated men over equally committed women. Despite Eula Gray’s essential role in founding the ASCU, for example, the Communist Party apparently never even considered appointing her to the position that Marcus Murphy came to fill. While the BSCP maintained a Ladies’ Auxiliary, which worked on organizing and fundraising, it always answered to the union’s male leadership and sought to support male workers, rather than organize women as workers themselves. (While sleeping-car porters were exclusively men, the BSCP did not consider supporting the introduction of women to the role.) Ultimately the unions proved unable to bridge the divide between Black and white workers and remained primarily Black unions until they were subsumed by the mainstream labor movement—after which they soon ceased to be unions at all.

While the ASCU, STFU, and BSCP had largely left the stage by the 1950s—the BSCP limped on until 1978, increasingly sidelined as automobile and air transit gained popularity—each left an indelible mark on the civil rights movement to come. The ASCU offered a model of regional organizing against white supremacy, similar to the local coalitions that would drive the struggle in the 1950s and 1960s. The STFU, which was founded slightly later and lasted longer—it would continue under various names until 1970, but ceased organizing sharecroppers in the South in 1946—had a more direct connection to the civil rights movement: its union members became part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, organizing and participating in sit-ins, freedom rides, and demonstrations, including the March on Washington in 1963. The idea for a March on Washington—which the BSCP’s Randolph helped lead—was spurred by an earlier mass march organized by Randolph in 1941; the planned protest against discrimination in the defense industries led Roosevelt to sign an executive order before it could take place. Other BSCP members were active in the civil rights movement, including E.D. Nixon, president of the Montgomery local, who helped organize the Montgomery bus boycott.

The tools at the disposal of these organizers were imperfect, but progress was possible. Randolph evoked the scale of the challenge in 1944 when he explained the necessity of Black unions amid the racist U.S. labor movement. He also made it clear that it was perhaps inevitable that the tactics of these unions would migrate to new battlegrounds, because there was no place in the United States that couldn’t benefit from what the organizers had learned in the labor movement.

There is no organization in America composed of white people which does not have some racial discrimination in it, but if the Negro is going to take the position that he should come out of every organization [that] racial discrimination is in he will come out of both the AF of L and the CIO. He will also come out of the church and the schools of America. He will refuse to go to Congress. In fact, this ridiculous position will lead him to the conclusion where he will be compelled to get out of America and eventually off the earth, for racial discrimination is everywhere.