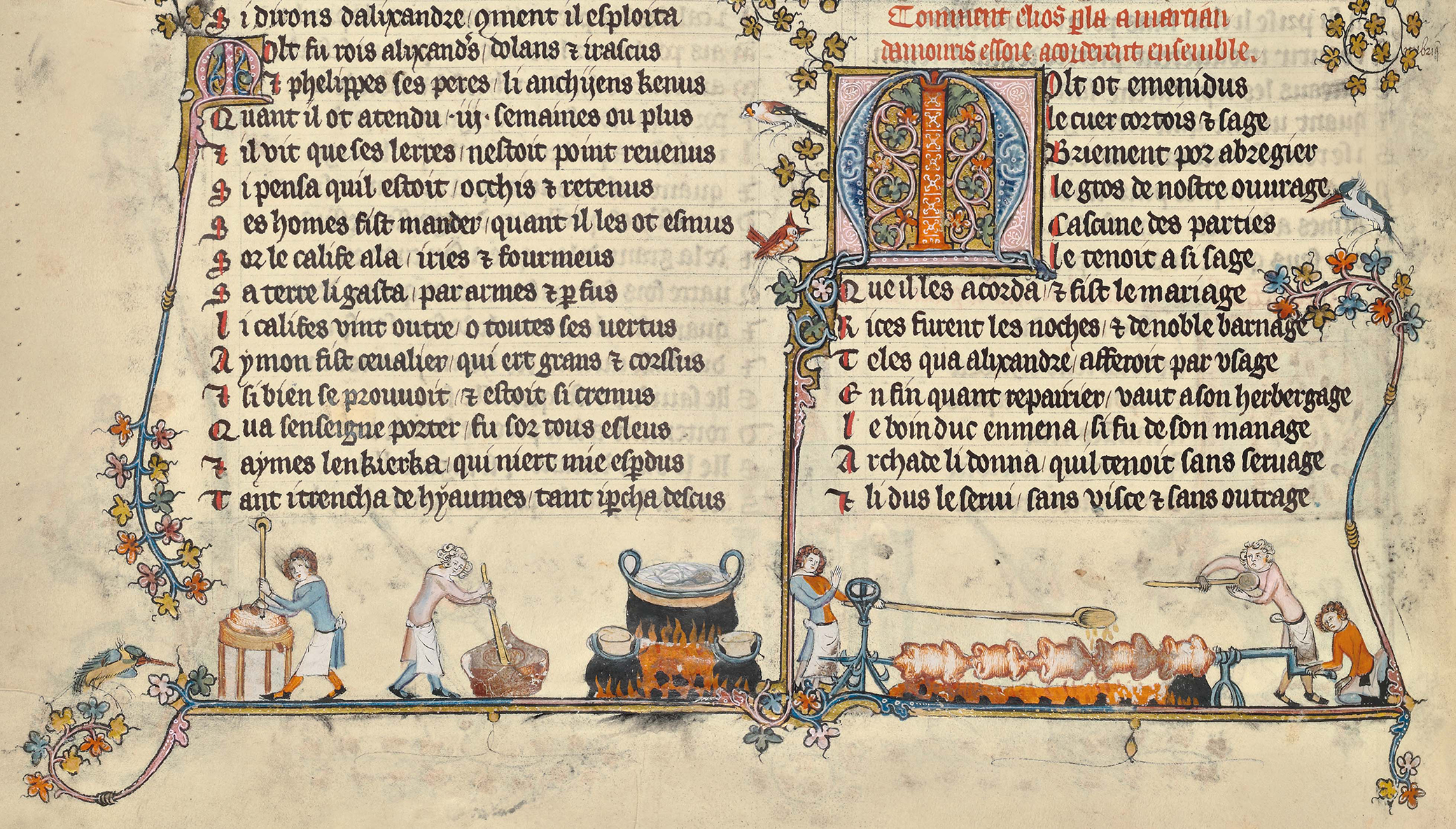

Detail from Romance of Alexander, c. 1338. © Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

The legend that noodles were brought to Italy by Marco Polo (1254–1324) is utterly spurious. The story was probably invented by the Macaroni National Manufacturers Association of America, and appeared in the late 1920s in their publication The Macaroni Journal.

The first forms of pasta probably arrived in Italy when the Arabs introduced a form of thin dried noodles called itriyya. We know from Muhammad al-Idrisi, the Moroccan-born geographer of Roger II, Norman king of Sicily, of a factory for dried pasta near Palermo in Sicily, which exported it to most of the Mediterranean. And a basket, or barrel, full of “macaroni” is mentioned in the inventory of the possessions of a soldier from Genoa as early as 1279, which confirms the importance of that area for dried pasta.

Lasagne and gnocchi were often mentioned in poems and tales from the end of the thirteenth century onward. In a humorous ballad recorded in a circa 1282 document in Bologna, two women textile workers go out on a drinking spree to a local inn, where they also manage to eat huge portions (seven plates) of gnocchi and lasagne. The great fourteenth-century storyteller Giovanni Boccaccio featured many pasta dishes in his Decameron, including macaroni and ravioli with butter and grated Parmesan.

The road of pasta toward global success was still far in the future, but by the fourteenth century the long journey of Italian pasta was truly underway, and England was one of the first places to adopt it.

One of the best known poets in the whole of English literature, Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343–1400), the son of a wealthy vintner, was sent on several occasions to Italy for diplomatic and trading negotiations. At least three trips are on record, and it seems impossible that a writer who showed an interest in the food available in London, and who included a cook among his travelers (many of whom were quite keen on the pleasures of the table) in The Canterbury Tales, was uninterested in Italian food. Unfortunately no letters or diary can support this claim, but we can speculate that when Chaucer was sent to Genoa in 1372–73 to meet the doge on behalf of the king of England to discuss the use of an English port by Genoese ships, he was offered some local specialties. At least two possible candidates spring to mind, given Genoa’s fame as a center for the production of dried pasta. Both are mentioned in thirteenth- and early fourteenth-century Italian manuscripts: lasagne and a kind of macaroni. Moreover we know that in 1351 some “master lasagne workers” were hired by a Genoese merchant ship, and therefore it is fair to assume that this type of pasta was popular and consumed by the crew.

A recipe for lasagne from this era is remarkably simple. White flour is mixed with lukewarm water, and thin sheets of the resulting dough or paste (pasta) are produced and left to dry. They are then boiled in a good broth, preferably made with capon or other fatty meat, and served layered with some good grated cheese in each layer. Another dish is specifically indicated as “Genoese.” This is another type of thin pasta, called tria (recalling the Arabic itriyya), cooked in almond milk, and mainly used for convalescents.

I am not, of course, claiming that Chaucer brought back the recipes, but in the oldest English cookery manuscripts, of the fourteenth century, collectively known as the Curye on Inglysch, we find some dishes that may have been inspired by Italy.

The first one is called losyns (or loseyns), and it probably refers to the type of pasta shaped as a lozenge, but the procedure is the familiar one of lasagne. And the recipe is virtually identical to that found in a fourteenth-century Italian Libro della cucina. Typically, the strips of pasta were dried, boiled, plated in three or four layers, and served with grated cheese and some sweet spices, mainly cinnamon. This addition of sweet spices might seem a little odd, but while staying with family and friends in Tuscany I decided to experiment with it. I used a form of wide, thick tagliatelle, and tossed the pasta with butter, grated Parmesan, a little cinnamon powder, and one ground clove. Although my guests were a little suspicious at first, my gamble paid off, and they all licked their forks clean: Renaissance-style tagliatelle went down a treat and kept those around my table very happy. The mixture of sweet and savory worked perfectly well, and the butter fried on a low heat until it became the color of hazelnuts made it wonderfully smooth.

No recipes, however scantily described, have survived either from the Anglo-Saxon period or from that of the early English kingdoms. But people did travel between Britain and the Italian peninsula—Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales, c. 1146–1223), for example, visited Rome three times, in 1199, 1201, and 1203—and they presumably reported some details about daily life and food in Italy.

It is difficult to establish links between culinary traditions in distant countries seven hundred or so years ago, but there were numerous opportunities for exchanges of practical information concerning crafts and trades, and food would have been a part of this. From the thirteenth century onward Italian merchants and bankers, especially from Lombardy and Tuscany, established trade contacts in the south of England to buy the excellent wool produced there. Lombard Street in London is a reminder of their settlement, and the cachet connected with this region has remained to characterize a number of dishes. Among the recipes collected in the Curye on Inglysch, apart from “Lombard rice” and “Lumbard mustard,” we also find leche lumbard, a spiced boiled pudding of pork, raisins, dates, and eggs in a sauce of wine and almond milk, with powdered cinnamon and ginger. The widespread use of almond milk as a basis for sauces or as a cooking medium may have come from Spain or Italy, both influenced by Arab cookery from the eighth to the tenth centuries, because as far as we know almond milk is never mentioned in Roman cookery.

Lasagne is not the only Italian dish to feature in the Curye on Inglysch. Here we also find a recipe for ravioles, a mixture of grated cheese with butter encased in little parcels made with thin layers of pasta. The ravioles would then be boiled in a tasty broth, laid out on a plate and served with melted butter and grated cheese “beneath and above,” and sprinkled with a pinch of ground spices, usually cinnamon and cloves.

Another recipe, which appears immediately after the ravioles, is also inspired by an Italian type of pasta, which was to have much success in the following centuries: macaroni. In Italian, as maccheroni, the word originally referred to pasta dumplings (gnocchi), and only later, in southern Italy, did it turn into the familiar tubular form. In the medieval English recipe, Makerouns look more like vermicelli (“little worms”), which only appeared later in England. The word maccheroni was traditionally explained as coming from Greek or Latin maccare, meaning to pound or crush. However, it is more likely to have been invented by the Arabs, as the word maqroun referred to little rings of pasta, made with durum wheat.

Recipes for meat dumplings often appear in England under the name of tartlettes, turteletes, or torteletys, the last being closest to the Italian original tortelletti. These pasta dumplings had different fillings, and in early Italian recipes they were also indicated by color: white ones were made with a filling of cheese, and green with a filling of spinach and herbs. These, like their Asian equivalents, such as Japanese gyoza or their Chinese relatives jaozi, could be boiled or fried.

Sometimes pasta dumplings even shed their pasta casings. The following dish is mentioned in a chronicle written by Salimbene de Adam, a Franciscan monk from Parma, circa 1282. He tells us that one day in August he ate, for the first time, some “ravioli without any pasta wrapping.” He pretended to frown upon them, as something certainly invented by gluttonous people, but obviously enjoyed them. They are still made in Florence, where they are known as gnudi or “the naked ones,” but they are also found in central and northern Italy, with various names, such as malfatti (the badly shaped ones) or green dumplings.

Literature often represents food as something to be desired. In his Decameron Boccaccio gives a vivid picture of a most extravagant land of plenty. There excellent ravioli and macaroni are cooked on top of hills made of Parmesan cheese and covered with vines tied up with sausages. Once ready, the pasta morsels start tumbling down the hill toward a stream of the purest and best Vernaccia wine. Readers of Boccaccio’s tales must have found these stories irresistible, so much so that they decided to go and check for themselves.

Gnudi

Serves 6–8 (10–12 gnudi per person)

1 kilogram (2 pounds) spinach

300 grams (10–12 ounces) ricotta (ideally made with ewe’s milk)

2 eggs

100 grams (4 ounces) freshly grated Parmesan

1/2 teaspoon grated nutmeg

50 grams (2 ounces) white flour

salt and pepper

a few sage leaves

First wash the spinach. To cook it, heat one teaspoon of olive oil in a large pan, add the spinach to the pan and a pinch of salt, and cover. No more water should be necessary. In about 3–4 minutes, the spinach should be ready. Remove and put in a colander. When cooled a little, make sure that you remove as much of the moisture as possible by squeezing it with your hands or by putting a weight over the spinach in the colander. Chop the spinach, and squeeze again if necessary.

In a large bowl, add the spinach to the ricotta passed through a sieve (or possibly, if it is very fresh, left to drain overnight). Add a generous pinch of grated nutmeg, the grated Parmesan, the eggs, and some salt and pepper. Mix well. Taste the mixture, and adjust the seasoning.

At this point, using some flour, start making fairly small-sized balls (about 3 centimeters or 1 inch in diameter) in your hands, adding more flour if necessary. Place all the naked ravioli on a tray or a clean cloth and sprinkle with a little flour. Boil some water in a large pan, add some salt, and then carefully drop the naked ravioli into the water. They will be cooked in less than 5 minutes.

Remove them carefully with a slotted spoon and arrange them in a well-greased oven dish, pour over some melted butter, then sprinkle over a few sage leaves and grated Parmesan. Slide under a grill for a few minutes and serve hot. In Tuscany they also serve them with a meat and tomato sauce, rather than grilling.

Excerpted from How We Fell in Love with Italian Food by Diego Zancani, published by Bodleian Library Publishing. Copyright © 2019 by Diego Zancani. Distributed in North America by the University of Chicago Press.