Humans were originally tropical creatures, and we are predisposed to like it warm. But not too warm: research shows that while the optimal temperature varies from person to person, it always lies between 70 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit. Despite this preference, our ancestors left the African savannahs 200,000 years ago to make their homes in significantly colder latitudes. People were capable of acclimating to freezing, life-threatening temperatures—but learning to love the cold required a journey of a different kind.

The cartographer Olaus Magnus, who was also the last Catholic archbishop of Uppsala, left one of the first accounts of life in the snow. In the sixteenth century he took lengthy voyages to remote areas of Norway and Sweden, and his report of these travels, A Description of the Northern Peoples, inspired interest throughout Europe. Illustrated with woodcuts and accompanied by a magnificent map, it provided a captivating, and sometimes fantastical, vision of the wild realm of the north and life amid ice and snow. In one memorable passage Magnus describes a symbolic horseback battle of the seasons on “the first day of May, when the sun enters the constellation of Taurus.” Riders on one side wore furs and represented the winter, while the other riders, in the role of summer, wore leaves and flowers. The opposing troops entered the town armed with lances, fighting until summer won the day. Symbolic struggles between the seasons were staged in places from Scandinavia to the Alps, taking the form of combat, debate, and dueling songs. But while the details and locations varied, the outcome remained constant: winter always lost in the end.

A heat wave is unpleasant and can be deadly, but low temperatures pose a far greater threat to life. Protection from this danger required humans to mobilize their powers of invention. For generations, winter’s icy embrace posed an enormous challenge. What can people eat when there’s nothing to harvest? How can they keep from freezing to death? And how can they move from one place to another when snow blocks every path and road? Answers to these stark questions represent many of civilization’s grand achievements. Having enough to eat, for example: from drying apples and pears to smoking fish and meat, pickling vegetables, canning plums, and curing bacon, nearly all techniques for preserving food emerged to help adapt to winter. The cold also fueled the development of heating and insulation systems. For vast stretches of time, the common way to heat an indoor space was simply to light an open fire. Stone fireplaces first emerged in the eighth century. By 1200 an efficient masonry oven was a fixture not only in monasteries and castles but in many private residences as well. While the subsequent centuries brought improvements in ovens, the underlying technology had its limits. One eighteenth-century aristocrat, Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate, Duchess of Orléans, left a vivid account of an insufficient oven in the otherwise sumptuous palace of Versailles. “It is such a fierce cold that it cannot be expressed,” she wrote on January 10, 1709, in a letter to Sophia of Hanover. “I sit by a large fire, have screens in front of the doors, have a sable around my neck, a bearskin wound about my feet, and for all the good that does I am shivering with the cold and can barely hold my quill. In all the days of my life I have never lived through a winter as raw as this one; the wine freezes in the bottles.”

But relief was in sight: central heating. The system, first making use of hot water or steam, was invented in the late eighteenth century. Its adoption was slow, and it long remained a privilege of the elite. The technology first appeared in nonaristocratic homes around 1900, and it remained far from standard for a long time after its introduction. With time, central heating was increasingly powered by oil or gas rather than wood or coal.

Heating systems went along with another technique for softening winter’s sting: keeping the cold out. When people first began to build small windows in their dwellings, they covered them with animal skins or linen designed to let in at least some light while retaining as much warmth as possible. Later, wooden shutters could seal windows when winter storms raged outside. Windowpanes were reserved for churches until well into the twelfth century and were considered the height of luxury for long afterward. If it got too cold, the solution for millennia was simply to seek refuge in bed: an entire family, along with their servants and guests, might find mutual warmth under the covers. Hanging curtains to create canopy beds or even building alcove beds into the wall provided another layer of heat-trapping protection.

But beyond the cold itself, humans faced another winter foe: the snow. Up until 150 years ago there was little anyone could do to counter the white blight but shovel it away. When snow made roads impassable, the only choice was to travel on ice. The routes traveled in summer and winter were often different: when snow hid the landscape’s features and pathways, people took the most direct route between two points. Horse- or ox-drawn sleds became the preferred means of transport. In the early days of rail travel, trains often got stuck in the snow. In January 1890, for example, a train traveling west over the Rocky Mountains came to standstill and the seven hundred passengers on board had to wait two weeks before their trip could continue. But as the nineteenth century drew to a close, rotary snowplows began to be attached to the front of locomotives, making it possible for trains to travel through deep snow.

In cities it was important to clear the streets quickly after a snowfall. An early solution involved flattening the snow with heavy rotating drums. Later on snowplows proved more effective but created a new problem: what should be done with the snow they piled on the sides of the streets? Getting rid of it was easier said then done. Transporting the snow outside of town or to a collection site required organization and money. And the snowplow did not spell the end of winter’s dangers or its ability to inspire creative problem-solving. In 1887 a New York inventor suggested using steam engines to power a network of heated pipes below the city’s streets and sidewalks to melt the snow away. The idea was never realized in New York, but other cities—including Reykjavík and Oslo—now have heated streets.

In March 1888 a legendary blizzard hit New York City, bringing wind gusts of more than eighty miles per hour. The storm knocked down power lines and brought traffic and the new elevated trains to a standstill. Horses froze to death in their harnesses, ships sank, and several hundred people died. For the next four days, the city was buried under three feet of snow, and drifts trapped many people in their houses. Sleeping cars stationed at railroad depots became emergency shelters. For the first time in its nearly hundred-year history, the stock exchange failed to open. But the traumatic winter storm led city planners to propose relocating telephone cables and public transport underground. A few years later plans for these ambitious projects were completed, and New York’s subway system was born.

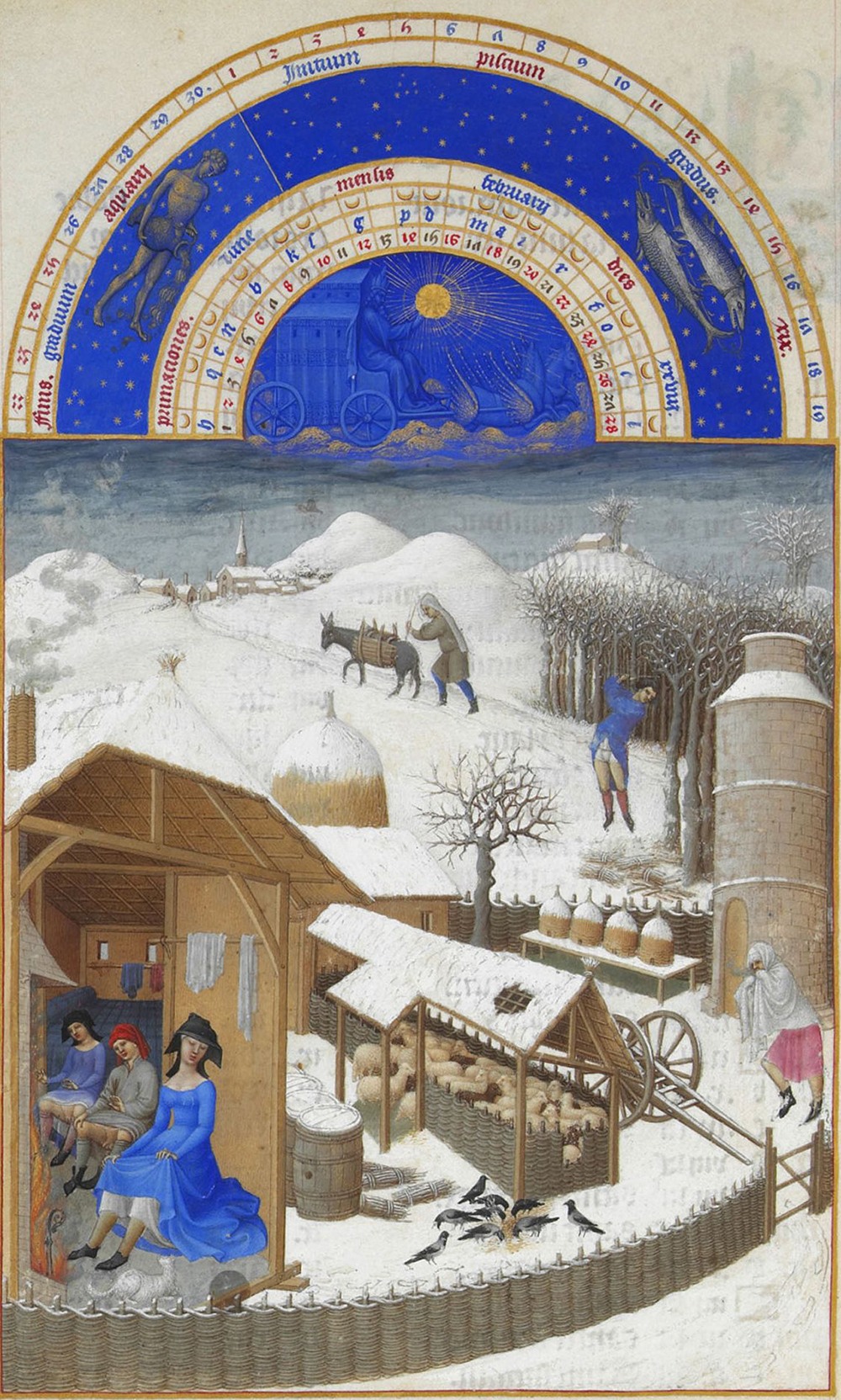

Paintings provide a glimpse of how people dealt with cold and snow in earlier times. But there’s a catch: the earliest depictions of the winter season date only from the fifteenth century. Before that no one took the trouble to draw or paint winter scenes. Did the limited color palette fail to inspire artists’ imaginations? Or was the winter so hated that people avoided showing it? Whatever the reason, the first known image of winter is the February illustration in the famous Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry manuscript, created circa 1414. The artist depicts woodcutters in a leafless forest, sheep huddled together for warmth, and birds picking through the snow in search of scattered feed. Works from the sixteenth century show that winter was not completely without its pleasures, however. Snowball fights and ice-skating were already popular, and Flemish and Dutch masters painted convincing scenes of people elegantly gliding over frozen ponds and lakes. There was even an early form of ice hockey, known as colf.

Building snowmen is another beloved winter activity that has endured since that time. Fashioning snow into a more or less convincing representation of a person represents a minor triumph over the forces of nature. The label “snowman” really applies only part of the time, as snow women flourished, too. In the late nineteenth century, for example, one snow artist captured a stunning likeness of Queen Victoria. The tradition of artistically ambitious snow sculpture stretches back to at least 1494, when Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici commissioned snow figures from Michelangelo for the courtyard of his palazzo. They were “very beautiful,” according to one observer, but exactly what they depicted before melting is unknown.

While winter offered certain pleasures, the idea that a winter landscape could be beautiful remained a rare sentiment for centuries. Snow, ice, and glaciers evoked negative associations. Traveling through the mountains during winter was dangerous, and people simply avoided it unless their obligations as tradesmen or pilgrims required it. It took a revolution in perception to make the wintry wilderness appealing. In the late eighteenth century a new obsession with nature as “wild” and “sublime” swept through much of the Western world. Mountains with snow-crowned peaks no longer seemed solely threatening—they also exerted an irresistible fascination. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, always ahead of his time, embodied this shift. He wrote about his Eislust, or passion for ice, which fed both his interest in mountains and his love of skating. In addition to local winter excursions into Germany’s Harz region, he made three trips to Switzerland’s majestic Gotthard Pass, starting in November 1779. Unlike the vast majority of Gotthard travelers, Goethe was not primarily interested in passing from one side of the Alps to the other. Instead he felt magically drawn to the “jagged ice cliffs” of the Rhône Glacier and the “vitriol-blue chasms” he glimpsed there. At the same time, the famous man of letters appreciated civilization’s adaptation to the winter. He became a particular fan of the Swiss masonry oven: “Indeed, it is most delightful to sit upon it, which in this country, where the stoves are made of stone tiles, it is very easy to do.”

Another half century passed before the first tourists stayed in the Alps over the winter. Up until then, any guests still holding out in a mountain hotel went scurrying to pack their bags as soon as the first flakes appeared. Johannes Badrutt, the business-savvy owner of the Engadiner Kulm hotel in St. Moritz, is celebrated as the father of winter tourism. According to legend, he spent a rainy evening in September 1864 by the hotel’s fireplace, talking to visitors from London. Badrutt claimed that on especially sunny winter days it was possible to walk around the area without a coat because of the warmth of the sun. He encouraged the English tourists to return in winter and see for themselves, offering to pay their travel costs if his account proved untrue. Travelers could not resist this intriguing bet and returned in mid-December—arriving under a bright sky and covered in sweat. They stayed until March. During these winter vacations, the main attractions were ice-skating and sledding. Skiing became popular later; at the Paris World’s Fair in 1878, skiing was touted as an exotic novelty. Norwegians can be credited with the spread of the sport, in particular a man named Odd Kjelsberg, who is said to have brought the first pair of skis to the Swiss town of Glarus. Christoph Iselin, a Swiss ski pioneer who took up the sport in 1891, supposedly only practiced in the dark at first so that he would not be laughed at.

For many children today, winter wears an unmistakable face, with chubby cheeks and white whiskers: Santa Claus. But since when have people associated winter with an old man? In Germany, a certain Herr Winter made a series of ever more frequent appearances starting in the mid-nineteenth century. He was the personification of ice, snow, and bitter cold. In 1848 Moritz von Schwind, an Austrian artist, drew Herr Winter for an illustrated magazine in Munich. For inspiration, von Schwind used figures based on Saint Nicholas, the fourth-century bishop of Myra. As the stern embodiment of the year’s coldest season, Herr Winter did not look good-natured. The Santa Claus we know, with his friendly smile and hearty ho-ho-ho, was a German-American coproduction. The driving force behind the evolution came from the United States: German-born Thomas Nast, a caricaturist in New York, adopted Herr Winter and gave him a friendly appearance. In 1863 Nast’s Santa appeared on the cover of Harper’s Weekly, distributing gifts to Union soldiers. This Civil War Santa wore a patriotic outfit of striped trousers, a fur coat with stars, and—appropriate for the occasion—a friendly but somber expression. Over the next three decades, Nast turned Santa’s simple hat into a pointed cap, and the coat became red, the beard grew white, and the face took on a merry expression. Nast is also likely the source of the story that Santa comes from the North Pole. But Santa Claus owes his real breakthrough to Coca-Cola. In 1931 the beverage giant hired illustrator Haddon Sundblom to create a version of the Christmas hero for an advertising campaign. Sundblom drew Santa Claus winter after winter for over thirty years.

Every year as Christmas nears, people around the world begin asking the same question: Will there be a white Christmas? It’s as if snow on Christmas were natural or fated—but is it? Climate researcher Martine Rebetez became interested in this question in the 1990s. She observed that people assumed that white Christmases had become less common over the years, but the statistical record suggested otherwise. Rebetez began examining Christmas illustrations in books and on greeting cards produced in nineteenth-century England. Her intriguing discovery: not a single picture featured snow until 1850, and only isolated examples of snowy landscapes appeared between 1850 and 1860. Then, a few years later, a winter wonderland became the standard backdrop for Christmas scenes. Because the custom of mailing preprinted Christmas cards to friends and family spread from England, people half the world over were soon sending cards evoking the magic of a white Christmas. Rebetez can only speculate about why snow so successfully infiltrated illustrators’ imagination of Christmas, but new travel habits may have played a role. The rush of British tourists to the Alps is one possible influence. In these high altitudes, snow at Christmas was essentially guaranteed. Images of the New England landscape, where Christmas snow was also common, may have been a factor as well.

Today ice and snow are losing ground as climate change progresses. It’s a paradox: now that winter is no longer an existential threat—thanks to new heating systems, insulation, and thermal coats—the snow is melting away. Winter often seems to be a mere shadow of its former self. And yet what happens when falling flakes are an ever rarer occurrence? Our longing for the experience of a “real” winter grows—and, as a consequence, so does the number of ways to satisfy it. Some people travel to places where winter still reigns. Every year tourists flock to snowy Lapland, for example. There they celebrate the cold and everything else that evokes the romantic ideal of “the North”: vast frozen wastes, endless nights bathed in the glow of the Northern Lights, herds of reindeer led through the tundra by Sami people in bright traditional clothing. Visitors hungry for more winter enchantment after a day of snowshoeing, dogsledding, or ice sailing on frozen lakes can spend the night in a “snow village” with elaborately constructed snow-and-ice structures. Perhaps the disappearance of winter also explains the growing popularity of activities like ice swimming.

Some scientists claim that the chronic warmth that surrounds us is unhealthy, causing heart disease and obesity; as countermeasures, they recommend cold showers, jogging shirtless, turning down the heat, or a full-body cryotherapy chamber. Temperatures as low as −150 degrees Fahrenheit are said to relieve rheumatism and arthritis, slow infections, boost athletic performance, promote weight loss, reduce depression, and fight aging. Now that it can’t kill us, winter is positively healthy.

Cold is not the only manifestation of winter that modern inventions try to re-create. Some are now attempting to duplicate one of winter’s smallest yet loveliest aspects: frost patterns. In the old days, nearly every winter window was a canvas for delicate crystal forms that grew into astonishingly plantlike shapes. “The ice on the windowpane forms itself into crystals according to the laws of crystallization, which reveal the essence of the force of nature that appears here,” mused Arthur Schopenhauer. “But the trees and flowers which it traces on the pane are unessential, and are only there for us.”

Since double-paned windows became the norm, however, window frost patterns have become a rarity. The situation puts a new twist on the plaintive words of the nineteenth-century German poet Friedrich Hölderlin: “Ah, where will I find Flowers, come winter?” Fortunately, today’s consumers can buy a solution in a bottle: ice-crystal spray, which can make convincing frost patterns on any glass or acrylic surface. “A winter backdrop in the summer—no problem!” declares one manufacturer.

If our longing for winter’s lost glories becomes too overwhelming, we can always seek solace in the library, where books provide a window to winters past. Henry David Thoreau offers us a memorable account of a New England winter in his 1843 essay “A Winter Walk.” Thoreau describes a field mouse sleeping in a cozy tunnel under the turf, an owl sitting in a hollow tree, and rabbits, squirrels, and foxes nestled in their respective shelters. “In winter,” he writes, “nature is a cabinet of curiosities, full of dried specimens, in their natural order and position.” Yet the season was not defined by stasis alone: “The recent tracks of the fox or otter, in the yard, remind us that each hour of the night is crowded with events, and the primeval nature is still working and making tracks in the snow.”

“In winter we lead a more inward life,” he notes. “Our hearts are warm and cheery, like cottages under drifts, whose windows and doors are half concealed, but from whose chimneys the smoke cheerfully ascends.” Faced with winter’s coldness and rigor, we become keenly aware of our own inner warmth. Perhaps that heightened awareness is what we will miss the most if winter ever truly leaves us.

Translated from the German by Lori Lantz.

For more on the history of winter, read Bernd Brunner’s Winterlust: Finding Beauty in the Fiercest Season, published this month by Greystone Books.