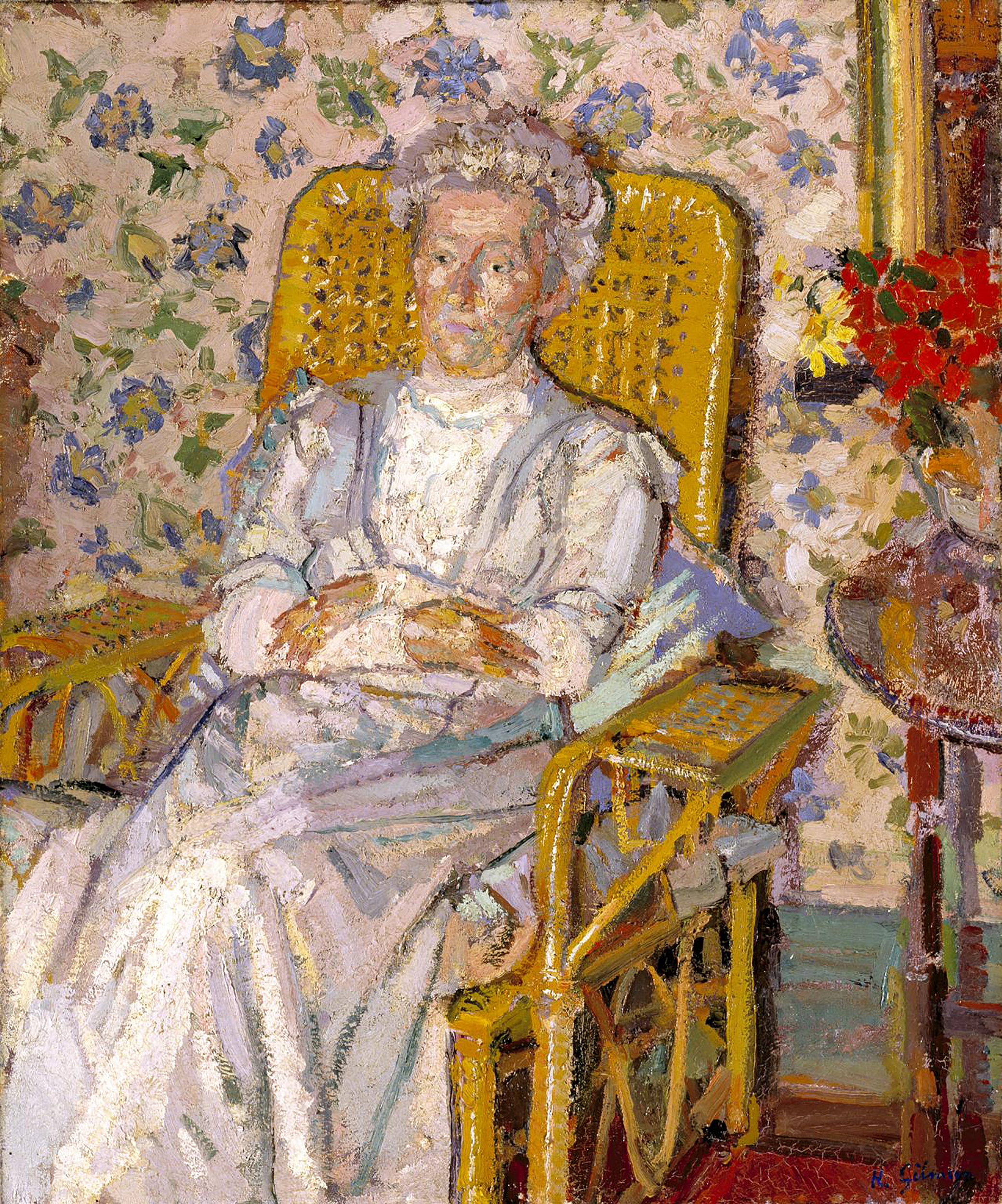

The Artist’s Mother, by Harold Gilman, c. 1913. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the history of best sellers, exploring the circumstances that might inspire thousands to gravitate toward the same book and revisiting well-loved works from the past that, due to a variety of circumstances, vanished from the conversation after they peaked on the charts. We are also publishing a digital edition of one of these forgotten best sellers, Mary Augusta Ward’s 1903 novel Lady Rose’s Daughter, with a new introduction, annotations, and an appendix. To read more about the project and explore the other entries in the series, click here.

It is 1942, and the United States has been at war for nearly a year. The men of America, however, are too excited about their moms to focus on fighting Nazis. Day by day, the defenders of democracy are turning into crusaders for “gynocracy.” Under the threat of global tyranny, even “drill sergeants are spelling out ‘MOM’ on the battlefield.”

And who, anyway, is Mom? She is a “human calamity” and “a cause for sorrow.” She “has “enfeebled a nation of once free and dreaming men.” She is “ridiculous, vain, vicious, and a little mad.” She is “cursed, unclean,” “reckless and unreasoning.” With her sinister psychic powers, she’s really a lot like Hitler.

Or so declares the writer Philip Wylie in his essay “Common Women.” First published in his best-selling 1943 collection Generation of Vipers, “Common Women” offered Wylie’s account of the “cult of mom worship”— “Momism,” as he notoriously deemed it—in contemporary life. By the time of Vipers’ publication, Wylie had already made a name for himself as a writer of popular science fiction novels such as The Smuggled Atom Bomb and Gladiator. A number of his books became the bases of successful Hollywood films, including the 1949 drama Night Unto Night, starring a young Ronald Reagan. But Vipers would become his most notorious and enduring work: a frenzied critique of American culture and institutions that encompassed everything from clergymen to chemistry. Over Vipers’ twelve bilious essays, Wylie painted an America of spineless conformists, incapable of recognizing or defending value. And yet Wylie saw himself as a patriot. His hope was that, by excoriating the nation—by exercising what he pedantically called his “critical attitude”—he could redeem it.

Reading Vipers—a book that roasts its readers, their moms, and the military for some three hundred pages—feels as patriotic as pantsing Ben Franklin. And yet Vipers sold some fifty thousand copies between 1943 and 1955, as Wylie boasts in the footnotes to the revised edition. I had learned of the book in a sort of Wikipedia-induced fugue state, clicking through a series of embedded links until I landed on Vipers and then on Wylie, a writer with the spiritual imprint of boarding school still visible in his face. Who were these readers, I wondered, who were willing to pay for put-downs from an Exeter graduate obsessed with nukes and Carl Jung? Apparently I was one of them.

To my surprise, the book was still in print, available in a stately white paperback reissue published in 2010. James Bowman, in a 2013 reappraisal of Wylie for The New Criterion, describes him as “so original that he’s almost unreadable.” There’s something hypnotic about Wylie’s self-aggrandizing pronouncements on American society; turning the pages felt like watching someone Photoshop their own face onto Mount Rushmore. For days, I’d find Wylie’s rhetorical hatchlings, like “the enwhorement of American womanhood,” squirming in my mind. Enwhorement! Perhaps I read the essays to catalogue these mutant phrases. Or maybe I read them for the footnotes, which transform Wylie’s best seller into a maniacal excursus on the experience of writing one.

“You are about to read one of the most notorious passages in American letters,” Wylie announces in the notes to “Common Women,” which are long enough to crowd the original text off the page. Full of preening anecdotes and pouting asides, Wylie’s notes, which appear for the first time in the 1955 edition, give the impression of a man circling the drain of his own mind, talking to and over himself. There was something poignant, and perhaps compensatory, about the marginalia of a writer so marginal. By the time I bought Vipers in 2019, Wylie had shriveled from public memory, but here he was, multiplying himself in the empty spaces of his own text. He had believed that his book would transform the psychological character of the nation and heal the ills of the age. Instead the book he wrote was just another symptom.

Born in 1902, Wylie grew up in Beverly, Massachusetts, the son of a Presbyterian pastor who reared him for a “mature, masculine life.” He grew up, predictably, to hate both the church and his father, leaving home first for Phillips Exeter Academy and then a few floundering years at Princeton, where he split his time between flunking classes, antagonizing professors, and brooding over the Daily Princetonian’s refusal to appoint him editor. After dropping out, he moved to New York, where he worked at a PR firm and attracted national derision when a woman named Elizabeth Hammond filed a successful paternity suit against him. high jinx in parsonage, read one newspaper headline, feasting on the indiscretions of a pastor’s son. Wylie would fulminate over “the Hammond affair,” as he called it, for the rest of his life. Disgraced but undeterred, he went on to publish a string of science fiction stories in The New Yorker, and soon married a model whom he described in letters as “sexually frigid.” She cheated on him prodigiously. He spent eight years “on amphetamines,” drinking so heavily that his wife would attempt, unsuccessfully, to have him committed.

After his divorce, Wylie turned his attention to what would become two lifelong passions: psychoanalysis and what he called the LIE, or the Liberal Intellectual Establishment. By 1933 he had remarried and moved to Miami Beach, where he wrote articles and appeared on radio shows advocating for “total war” against Germany. Soon after, he was recruited to chair the Defense Council in Dade County, where eighty thousand Air Force ground forces were stationed for training; Wylie and the council’s leadership worried about the possibility of a German attack on the training site. After the attacks on Pearl Harbor, he relocated to Washington, DC, at the behest of the Defense Council and became convinced that “intellectual pacifists” in government were stymieing FDR’s response to Hitler.

Vipers emerged from this period of political frustration: it was both Wylie’s “private catharsis” and a “catalogue” of everything “spiritually, morally, and intellectually” wrong with his “fellow citizens.” He wrote the manuscript over a six-week period in 1942, spurred by his frustration with the lethargic pace of the war in Europe and the government’s “apathetic” response to Pearl Harbor. America’s craven foreign policy, he believed, revealed a cultural rot. Chief among the nation’s afflictions was the “Oedipus complex,” which had become “a “social fiat and dominant neurosis in the land.” Wylie had long believed in the liberating power of the “psychodynamic ideas” of Carl Jung, and hoped that his essays, which he claimed were “derived” from Jungian insights,” would help readers loosen the constraints of the unconscious.

As part of this lofty yet nonsensical endeavor, Wylie produced Momism, a nasty piece of pop psychology well suited to the demands of the zeitgeist. “Common Women” was to be a Jungian exorcism: by expelling Mom’s possessing spirit from the collective psyche, the nation would finally achieve a state of manly self-knowledge and defeat its enemies abroad. Crude applications of psychoanalytic theory had come into vogue in postwar culture, and a Wylie reader was well primed to see shades of Momism in everything from Psycho’s Norman Bates to the ardent, aching performances of male Hollywood icons like Marlon Brando and James Dean. Roger Ebert, reflecting on Nicholas Ray’s classic film Rebel Without a Cause, speculated that Momism had “served as inspiration for the novel on which the film was based.” Indeed, the film’s depiction of an apron-wearing emasculated father, alongside Dean’s tortured vulnerability as the film’s adolescent antihero, chimed with Wylie’s account of the softening of the American man. Wylie’s insistence that mothers had acquired too much influence—over the home and over the nation—found traction in a postwar boom economy where women wielded a new degree of purchasing power and cultural visibility.

Vipers, with its acrid depiction of the U.S. military, seems an unusual success for 1943, a year that saw the publication of best-selling nonfiction titles such as Richard Tregaskis’ Guadalcanal Diary and Ernie Pyle’s Here Is Your War, both paeans to the armed forces. But by 1945 Generation of Vipers had sold 75,000 copies; as of the publication of the annotated 1955 edition, the book had sold 180,000 copies and gone through twenty printings. In 1950 the American Library Association declared it one of the most important works of nonfiction of the first half of the twentieth century. Wylie’s previous book, the 1934 novel Finnley Wrenn, had sold only nine thousand copies in its first printing; after Vipers’ success, it went on to sell over a hundred thousand. Praised by the New York Times and by Malcolm Cowley in The New Yorker, Vipers boasted admirers as unlikely as Simone de Beauvoir, who lauded Wylie for “brilliantly” describing the “reign of the matriarch” in American society. The book found a receptive audience among psychiatrists, including the influential doctor Karl Menninger, who compared Vipers favorably to his own 1942 best seller, Love Against Hate, in a letter to Wylie. The psychiatrist Edward A. Strecker credited Wylie, somewhat grudgingly, as an influence on his 1946 book Their Mother’s Sons: The Psychiatrist Examines an American Problem.

Read more about The Slow-Burn Best Seller

The writer and scholar Stephanie Coontz locates Wylie in a cohort of postwar writers who attempted to make sense of generational changes in American life by pathologizing American women. In Their Mothers’ Sons, Strecker argued that overbearing mothers had made their sons unfit for duty, resulting in the 2.5 million men discharged from the army. In 1947 came Modern Woman: The Lost Sex, a work by sociologist Ferdinand Lundberg and psychiatrist Marynia F. Farnham arguing that “contemporary women are in very large numbers psychologically disordered,” and in many cases bequeath their neuroses to their children. Like a misogynist retelling of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, Wylie’s “Common Women” indicts the cult of domesticity while framing men as its primary victims. And while the essay scandalized readers, it gave him cover for his most un-American ideas as well as a veneer of sociological legitimacy.

In his preface to the 2010 edition, the writer Curtis White hails Wylie as a “Nietzschean vitalist” who probes the “discrepancy between what we claim as right and what we are.” The comparison is a wishful one, to say the least. Vipers’ success owes more to the author’s misappropriation of psychoanalysis than to any philosophic insight. It’s easy to understand why Vipers and similar pop psychology books were so successful; in repackaging psychoanalysis for American readers, these books shoehorned a challenging school of thought into a consoling worldview. Ultimately, Vipers reads like self-help for chauvinists: a do-it-yourself guide for overcoming the Oedipus complex and winning the war. The language of neurosis becomes a tool for shoring up national supremacy. Rather than complicating our understanding of the self, books like Wylie’s, Strecker’s, and Menninger’s suggest that the human psyche is easily understood and more easily repaired. Just get a handle on the mommy issues and you’ll hit two birds with one stone: girly boys and global fascism.

Wylie wanted to liberate the nation from “diseased serfdom.” Instead he was “forever tagged as Woman’s Nemesis,” as he laments in the footnotes. The book had failed to transform his “great nation” as he hoped it would. Men continued to love and hate their mothers in the same proportion as before. “My risky efforts,” he wrote, to “sever the psychic umbilicus” attaching men to their mothers “achieved nothing.” But one wonders what was so “risky,” really, about Wylie’s tired rehearsal of misogynistic tropes, his obsession with bedwetters and ballbusters. Indeed, “Common Women” buoyed the success of Generation of Vipers, whose other essays scarcely merited comment in the press. Despite courting outrage, “Common Women” merely ratified prevailing anxieties about women’s social influence while securing Wylie’s reputation as an intellectual iconoclast.

Only in one essay, titled “Businessmen,” does Wylie offer an unorthodox opinion: that modern society, from urban design to the automobile, conspires in the service of capital. “Maybe we are staring at the decline of the West,” Wylie wonders after thirty pages of ruminations on the approaching era of “managerial feudalism,” “public thievery,” and the “fundamental immorality” of American businessmen. By the time Vipers was reissued in 1955, the flourishing of American leftism in the 1930s and ’40s had come to be known by cold warriors as the “twenty years of treason.” Even the intelligentsia found themselves on the front lines of the cultural Cold War, populating the mastheads of secretly CIA-backed periodicals such as Encounter and The Partisan Review. Against this backdrop, “Businessman” argued that, American consumer culture, like Communism, “attributes all social ills to an improper or insufficient distribution of junk.” Of course it’s vapid to equate a consumerist society with a Communist regime on the grounds that both depend on things. And yet the essay still mounts a more formidable critique of American values than anything in “Common Women.” Wylie’s readers, however, showed little interest in his skewering of McCarthy and the icons of free enterprise. It was “Momism” that seized his readers’ imaginations while affirming their prejudices. Far from braving controversy, Wylie’s anti-mom diatribe overshadowed his attack on entrepreneurialism, aligning Vipers with the mores of midcentury America.

Ultimately, Wylie’s book was not an indictment of the zeitgeist but a distillation of it: a relic of a time, as Coontz writes, “when we hated Mom.” Like the “psychic umbilicus” leashing men to their mothers, Wylie’s success yoked him to his most hated subject. After Vipers, wherever Wylie went the specter of Mom followed, always reproving, always remembering, outlasting even the writer himself. Far from defeating the Oedipal complex, Wylie became its perfect avatar: a man rhetorically wedded to Mom in both life and death. philip wylie, writer, dies; noted for “mom” attack, read the headline of his New York Times obituary.