Shakespeare Memorial Library bookplate, 1895. Folger Shakespeare Library.

None of William Shakespeare’s friends and associates left behind a description of his library. Nor is there a record of it being dispersed at the time of his death. His will refers neither to books nor manuscripts. In fact, it gives no sign of a literary career at all, or even a literate one. Contemporary dramatists such as Francis Beaumont, Thomas Dekker, John Fletcher, Robert Greene, Thomas Heywood, and Ben Jonson all left behind plays in manuscript. No Shakespeare playscript, though, has ever been found. (Part of the manuscript of a play about Sir Thomas More has been attributed to Shakespeare, but the part is small and the attribution contentious.)

We do, however, know a few things about Shakespeare’s relationship with books. He wrote plays according to a method that has been labeled plagiaristic; “appropriative” is a more polite term, and historically more accurate. Quantities of prior plays, poems, novels, histories, and almanacs fed into his writing. The breadth of his sources is exceptional; they number in the hundreds and span diverse eras, countries, and genres. By some means, Shakespeare had contact with most or all of these source texts.

During his career, a network of libraries linked bookmen to one another. Jonson, for example, used Francis Bacon’s library, and John Florio used the Earl of Southampton’s. Shakespeare probably knew John Bretchgirdle’s clergyman’s library in Stratford and printer Richard Field’s working library in London. Shakespeare referred to libraries as “nurser[ies] of arts” (in The Taming of the Shrew) and characterized them as treasure troves and cure-alls. Titus Andronicus invites Marcus Andronicus and Lavinia to “Come, and take choice of all my Library, / And so beguile thy sorrow.” The Tempest seems to have been written late in Shakespeare’s life. Many scholars have read it as his theatrical farewell, and the sorcerer Prospero as his alter ego. Prospero tells Miranda, “Me, poor man, my Library was dukedom large enough,” and later confesses: “Knowing I loved my books, he furnished me, from my own Library, / With volumes that I prize above my dukedom.”

Doubtful oral traditions have come down to us as well. One anecdote concerns Ben Jonson, with whom Shakespeare seems to have maintained a complex relationship of mutual affection and perpetual jousting. The anecdote sees Jonson “in a necessary-house” (in other words, on the lavatory) “with a book in his hand reading it very attentively.” Shakespeare notices Jonson thus engaged and says he is sorry Jonson’s memory is so bad he cannot “sh-te without a book.”

If Shakespeare had a library, we can readily visualize its contents. Apart from working drafts, along with manuscripts and copies of his principal literary and historical sources, he probably owned reference works: writing guides, dictionaries, and foreign-language instruction manuals. Examples of the latter include Claude de Sainliens’ A Treatise for Declining of Verbes (1590); Sainliens’ The French Littleton: A Most Easie, Perfect and Absolute Way to Learne the Frenche Tongue (1591); William Stepney’s The Spanish Schoole-master (1591); John Eliot’s Ortho-epia Gallica (1593); and G. Delamonthe’s The French Alphabet, Teaching in a Very Short Tyme, by a Most Easie Way, to Pronounce French Naturally, to Reade It Perfectly, to Write It Truely, and to Speake It Accordingly (1592). All these titles were printed or published by the Stratford-born bookman Richard Field.

Of the many hundreds of book owners I’ve studied, the overwhelming majority left behind evidence of their ownership—bookplates, book labels, signatures, marginal notes, manicules, inscriptions, imprecations. That is the case today and it was true, too, of book collectors in Shakespeare’s day. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century collectors often wrote their names on title pages or other leaves of their books. John Bretchgirdle was vicar of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford. He probably baptized the infant William Shakespeare, and certainly had one of the best libraries in town. On each of his title pages, Bretchgirdle wrote “Jo. Bretchgyrdles Book,” along with details of where he bought the book. Edward Alleyn wrote his name twice in his books, once on the title page and once on the verso of the last leaf. Among other Shakespeare contemporaries who were also book-markers, Ann Raynor used a tidy and legible script to sign her books on the inside of the front cover, while Humphrey Dyson ink-stamped the date on his books in a manner as idiosyncratic as a signature.

Apart from writing “Will: Boothby” on his title pages, Sir William Boothby had his books bound in armorial calf, goatskin, and vellum. A folio volume from his library, now in a private collection, is bound in calf with raised bands that divide the spine into even compartments, each one featuring Boothby’s lion’s-paw crest stamped in gold. The sixteenth-century book collector Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, also had his books bound in personalized leather covers. Those bindings were decorated with his initials and his coat of arms—a muzzled bear chained to a ragged staff—stamped in gilt on the upper cover. Dudley’s home was Kenilworth Castle, near Stratford-upon-Avon.

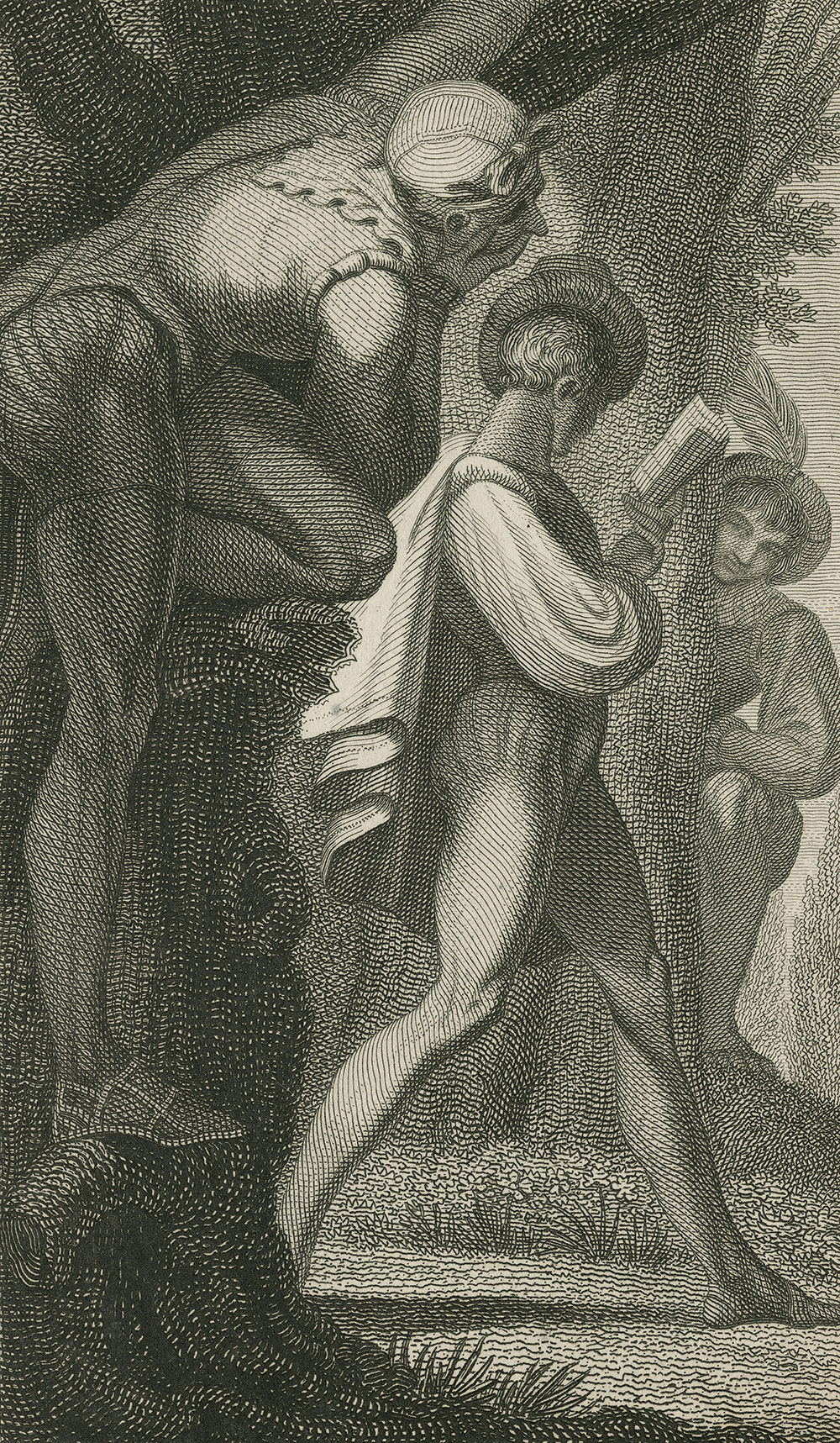

Mystery and controversy surround the Shakespeare family arms and motto. In 1596 the College of Heralds granted a coat of arms to John Shakespeare. Most scholars believe the College was responding to an application from William Shakespeare in his father’s name. Unlike John, his son could afford the steep cost and possessed the steep ambition to apply for a crest. The Shakespeare application was not smooth sailing; it had to be submitted more than once. A supplementary request to combine the crest with that of the Arden family was rejected.

The application was so controversial that the Shakespeare arms were cited as a factor in the 1602 complaint by a heraldry official that coats of arms were being granted to undeserving commoners. The Shakespeares’ application does appear to have exaggerated their wealth and over-egged their connection to the better sorts of Ardens, who had lived in the district since at least 1438. The Shakespeares may also have paid a bribe in lieu of proof of their noble lineage. They could not prove, for example, that a warrior ancestor had defended Henry VII—because he almost certainly had not. Nevertheless, William Shakespeare was soon referring to himself as a “gentleman.”

The final “letters patent” version of the Shakespeare family arms has been lost, but we do have drafts and a detailed description: “Gold, on a Bend, Sables, a Speare of the first Steeled Argent. And for his creast or cognizaunce a falcon, his winges displayed Argent standing on a wreath of his colours.” Variant versions add a helmet and tassels. The spear was an unavoidable inclusion (and, in gold and silver, an aspirational one). Complementing the arms was the motto Non sanz droict, “Not without right.” The claim, sometimes made, that Shakespeare used this motto on many of his documents is patently false. On nearly all the surviving documents the motto is absent. It seems to have been composed specifically for the arms application. (An alternative theory, not widely accepted, is that the motto is not a motto at all but a record of the application’s initial rejection—Non, sanz droict, “No, without right,” the comma making all the difference.)

The search for Shakespeare’s library provides an intriguing perspective on his purchase of arms. Was he assembling a collection of books that he would clothe in beautiful calfskin and morocco? Was he planning to display his heraldic crest on the books’ front covers and spines? Did “gentle Shakespeare,” in other words, yearn for a proper gentleman’s library? Every connoisseur of leather-bound tomes would swap a limb for an original volume displaying Shakespeare’s crest. With my wife, Fiona, I’ve searched far and wide for just such a volume.

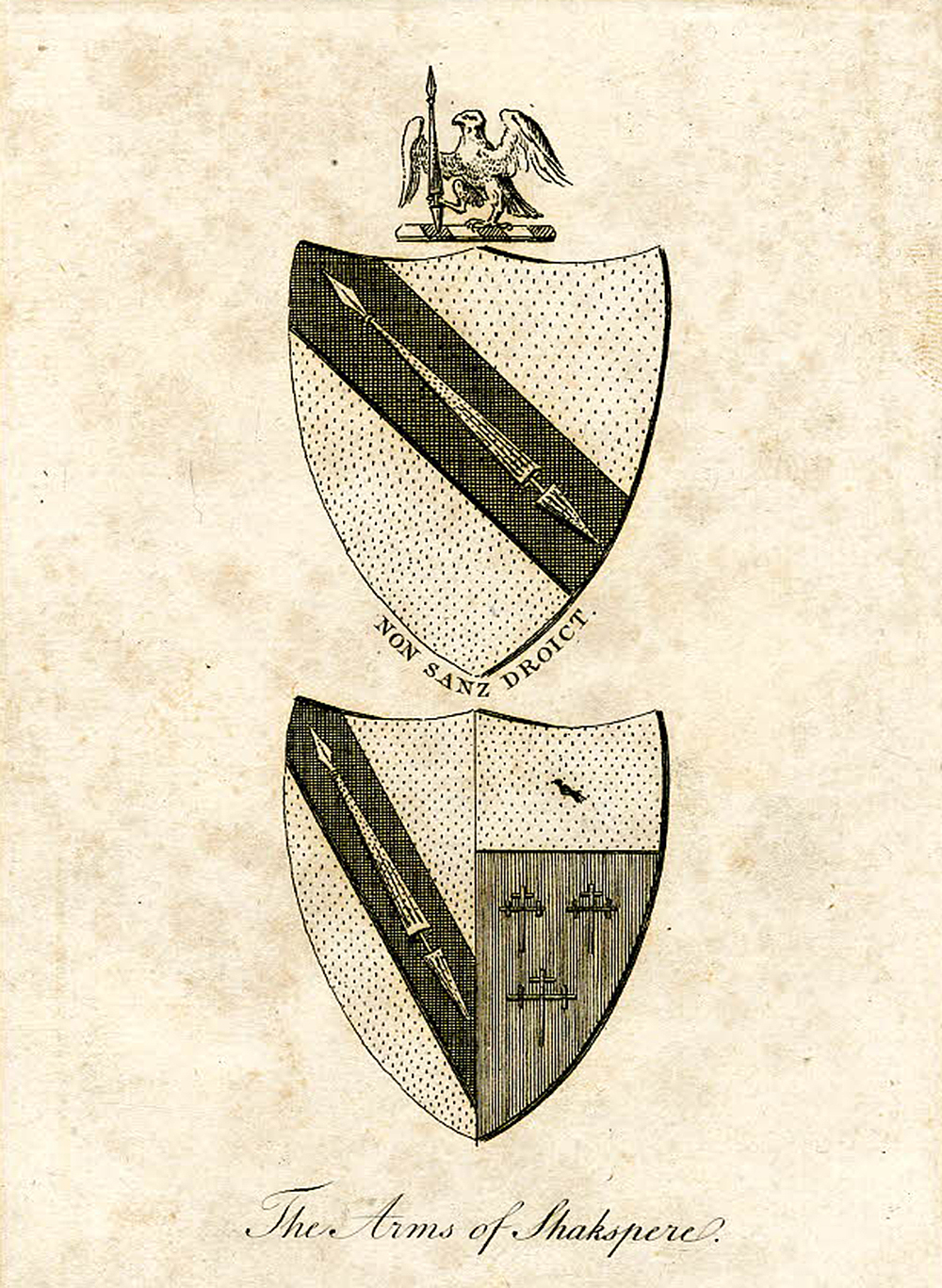

A few of our finds are exciting and suggestive. Perhaps the most intriguing one was previously owned by the Lane family. A theological work by Agostino Tornielli, it was published in Milan in 1610, then shipped to England where, in 1615, it was bound in brown calfskin in a distinctive style. The book’s spine is divided by raised bands into eight compartments decorated with golden sprays of laurel. The cover panels feature a rectangular decoration with, in the center, an image blocked in gilt showing the tragic story, from Ovid and used by Shakespeare in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, of Pyramus and Thisbe. (The story also influenced Romeo and Juliet.) In the image, Pyramus lies on the ground, expired, and Thisbe ends her own life by spearing herself on an upright sword. A lion flees but Cupid stays to watch the spectacle.

Apart from the handsome leather cover, the edges of the text block are beautifully decorated with elaborate patterning: snail and lion motifs within laurel wreaths on a field of gilt “fleurons,” or printers’ flowers. Three other bindings in the exact same style, with the exact same gilt block, have also been documented. All four volumes date from before the year of Shakespeare’s death, except for one which was bound in that year. The latter volume, bound in black turkey, is especially notable because it is a copy of Ben Jonson’s Workes (1616), a book closely connected to Shakespeare.

The owner of the four bindings is not known, but there are a few hints. Do the fleurons signify a literary career? That would fit the depiction of Pyramus and Thisbe, which suggests a deep interest in literature (the owner chose a literary motif over a royal, ecclesiastical, political, or military one) and possibly a deep interest in Shakespearean literature. In tiny letters, the cover image is signed “I.S.” No one knows whether the initials are those of the block-maker, the bookbinder, the bookseller, the book’s owner, a patron, or a dedicatee. No one has stepped forward to claim them. One person with those initials is “Iohannes Shakespeare,” William Shakespeare’s father, a man who made part of his living by dealing in leather hides, no doubt some of them for bookbinding.

Sotheby’s sold the book in 1926. Maggs Brothers of London bought it then sold it to Henry Clay Folger. It is now in the Folger Shakespeare Library, not attributed to any early owner.

Apart from this intriguing foursome, Fiona and I found many other armorial bindings from the right period. Not one of them, though, displays Shakespeare’s crest. Not one of them is conclusively traceable to his library. Nor have we found a Shakespeare bookplate.

If he was indeed assembling a fine library, we know a little about what Shakespeare’s books might have looked like. In the middle and later decades of the seventeenth century, the rise of Puritanism shifted bookbinding fashions towards simplicity and austerity; rich decoration was a radical and dangerous act. But in Shakespeare’s day the most delightful bindings were sumptuously decorated with gilt ornamentation: stars, dots, blocks, chevrons, cartouches, centerpieces, arabesques, ellipses, flowers, diamonds, rolls, and scrolls. Rooms of books bound in this way look like collections of jewels.

Thinking about Shakespearean bookbindings sparks off other exciting thoughts. Robert Southey’s “Cottonian Library” consisted for the most part of books bound by his daughters and their friends in floral cotton remnants. The delightful homecraft bindings make the books look soft, fresh, warm, and eminently embraceable. Shakespeare probably was entitled to keep his own acting wardrobe. Imagine Shakespeare’s children covering his books in fragments of the knotted and embroidered costumes he wore when playing the Ghost in Hamlet, and that his children and grandchildren wore when playing games of Scaramouches. What would such an artifact be worth? What would it tell us about Shakespeare’s life and character?

Excerpted from Shakespeare’s Library: Unlocking the Greatest Mystery in Literature, by Stuart Kells, published by Counterpoint Press. Copyright © 2018 by Stuart Kells. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint Press.