“Mammy Kitty,” c. 1860, ambrotype. Ellis Family Daguerreotypes, Accession #2516-c, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

During the 1840s and 1850s, the rise of photography unleashed a radically new way for American slaveholders to depict, possess, exchange, and preserve knowledge about the world of southern bondage. As itinerant and urban studio photographers spread throughout the South, masters and mistresses did not simply seek to represent themselves. Slaveholders in cities and on farms and plantations made slave photographs—in the cosmopolitan centers of Richmond, Savannah, and Charleston as well as in rural areas such as northern Florida, central Virginia, and northwest Mississippi. Despite the temptation to treat these images as unmediated access into the American past, they deserve to be explained for how they operated in their world rather than ours.

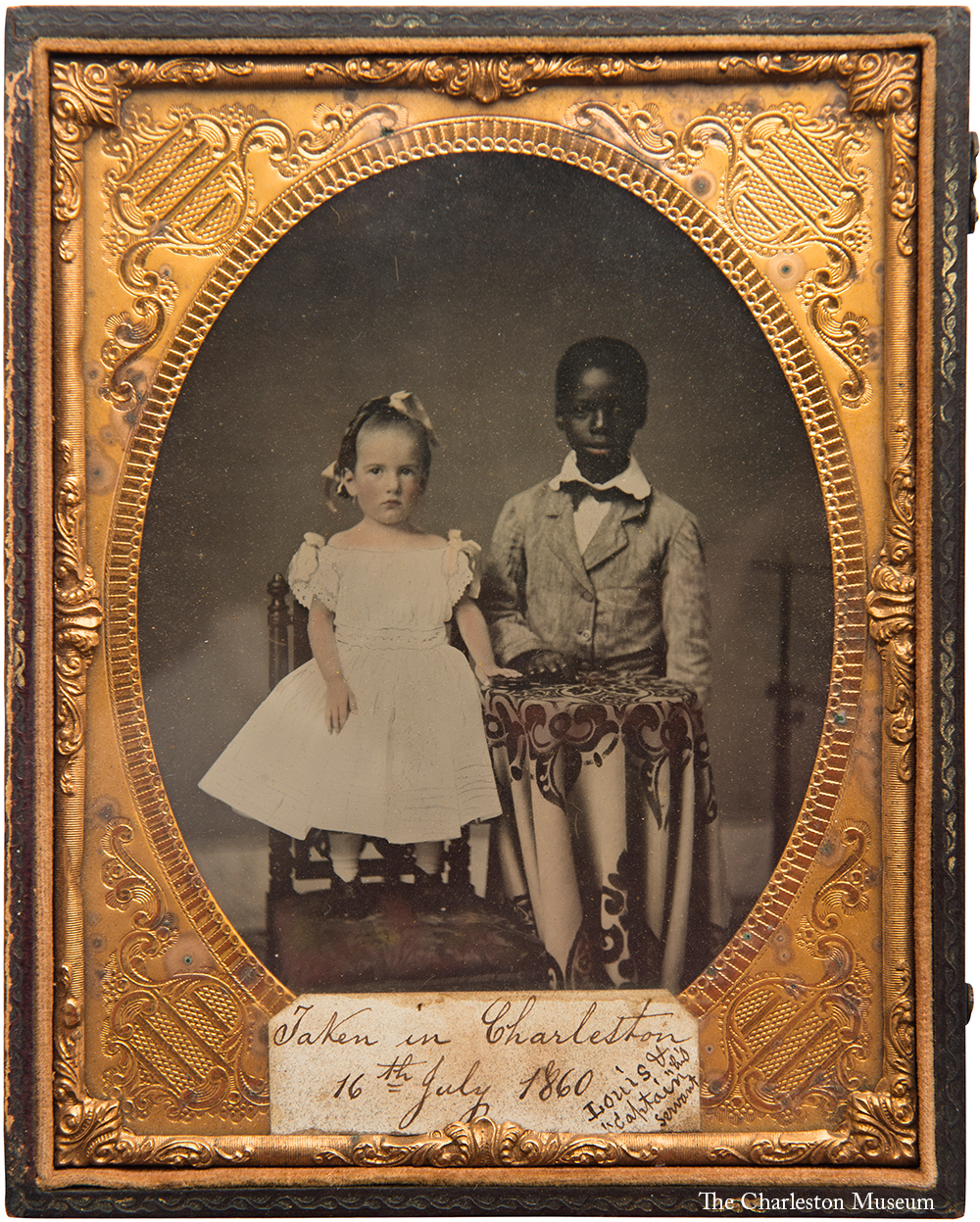

In the contentious political climate of the late antebellum era, slave photographs gave slaveholders a powerful new evidentiary tool to envision and perform a benevolent and intimate regime. Through the circulation and display of images of well-dressed bondspeople and portraits of enslaved caretakers with white children, enslavers projected a comfortable, harmonious, and familial form of bondage, which purportedly treated its laborers as people, not commodities. In the late antebellum era, slave photographs and their attendant photographic practices emerged as a key means for enslavers to persuade themselves and others of the just and beneficial nature of slavery.

But in the making of slave portraits, especially individual portraits, owners produced a problematic contradiction: slaves were categorically denied full personhood in southern law and culture, yet the conventions of photographic portraiture theoretically suggested the uniqueness of those bondspeople sitting before the cameras. Could it be that slaveholders spent time, energy, and money on images that actually asserted the full humanity of their property? Was it possible that photographic portraits of slaves revealed, as photographer Marcus Root put it, “that individuality or selfhood, which differences him from all beings, past, present, or future”?

Though they never stated so explicitly, slaveholders evidently sensed the dangers of these implications. Visual evidence, private letters, and diaries reveal how owners walked a fine line between elevating and subordinating their slaves through photography. Enslaved people could pose, but they were limited to certain poses. Slaves’ clothing and postures might suggest bourgeois respectability, but slaveholders consistently undercut that status as they discussed and displayed slave photographs. Limiting slaves from realizing the full spectrum of social identities and character traits available to whites was a subtle but vital means of maintaining the imaginative boundaries that divided enslaved from free. After 1839, the very photographic practices that helped owners insist their slaves were not treated as commodities simultaneously amplified the cultural denial of full personhood.

Owners made the abstractions of “slavery” and “mastery” concrete through miniature photographic depictions and social performances. They constructed and enacted a benevolent, intimate form of slavery for themselves and those in their social circles, one that implicitly and explicitly rejected the notion that slaves were viewed and treated as commodities. But slave photography actually constituted a precarious tool of power for southern slaveholders. A photographic portrait also made claims about the identity of the enslaved sitter. The very same portraiture conventions used to convey a humane form of bondage simultaneously implied the individuality and subjectivity of the enslaved sitter—at least in theory. This was the bargain slaveholders made, consciously or not, when commissioning slave portraits. Elevating favored slaves helped owners to rationalize bondage and to perform a benevolent form of mastery, but elevating the slave too much imperiled the ideological foundations of their world. How slaveholders dealt with the implications of slave portraits is partially revealed in written records. Rare diary entries, private letters, and paper notes attached to photograph cases reveal how southern whites articulated what slave photographs conveyed and confirmed. Time and time again, slaveholders sought to define, undercut, and limit slaves’ expressions of humanity. Photography created a venue that cast enslavers as the arbiters of enslaved people’s social identities.

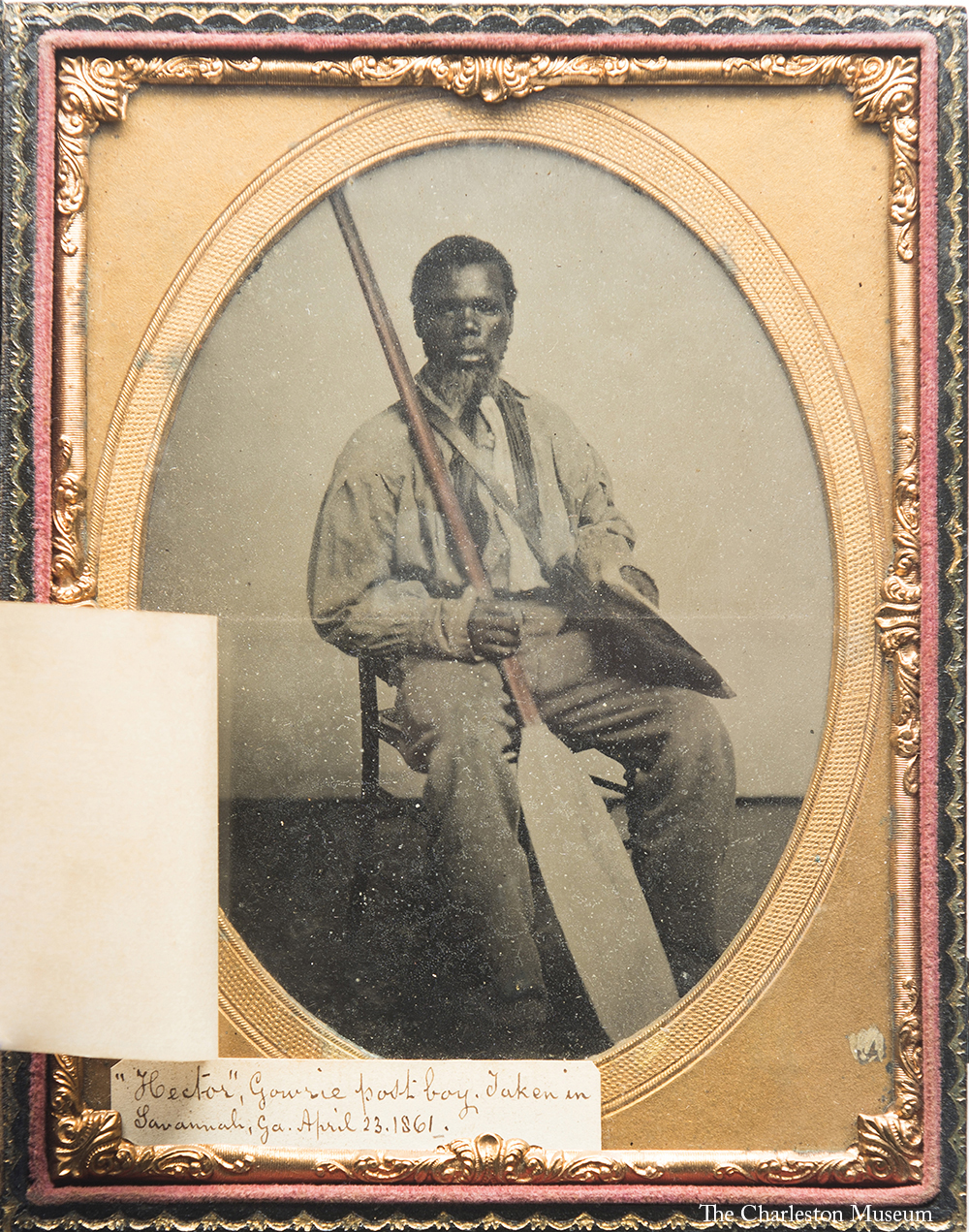

Slaveholders framed these photographs as acts of intimate possession over their slaves, rather than as vessels for slaves’ self-expression. A boatman as well as a favored slave at Gowrie plantation outside Savannah, Hector often traveled to the city to deliver mail and obtain supplies for Louis Manigault. In 1861 Hector posed in the full-length portrait necessary to capture his oar. Hector’s image was part of the broader genre of “work photography,” one that emerged as the daguerreotype became less expensive. It permitted all types of workers to pose with their tools, as in the case of Isaac Jefferson, a free blacksmith and the former slave of Thomas Jefferson, whose apron, hammer, bare arms, and exposed chest signified his labor. Hector might have taken a pride in his image similar to that which Jefferson took: the oar that dominates the picture suggests the geographic mobility prized by enslaved boatmen; the newspaper suggests how Louis Manigault depended upon Hector to bring him news from the outside world. Yet Louis Manigault made sure to assert his control over Hector. As Manigault would later write, “In this picture I had him taken with his paddle in one hand, and a newspaper in the other, with the Gowrie plantation mail-bag over his shoulder.”1 Manigault enveloped Hector’s possession within his own authority. Hector could claim “his paddle,” but Manigault claimed ownership over Hector and mastery over the photographic process: he framed this photograph as an act of possession. Hector could strike a pose, but this was only a product of his master’s bidding.

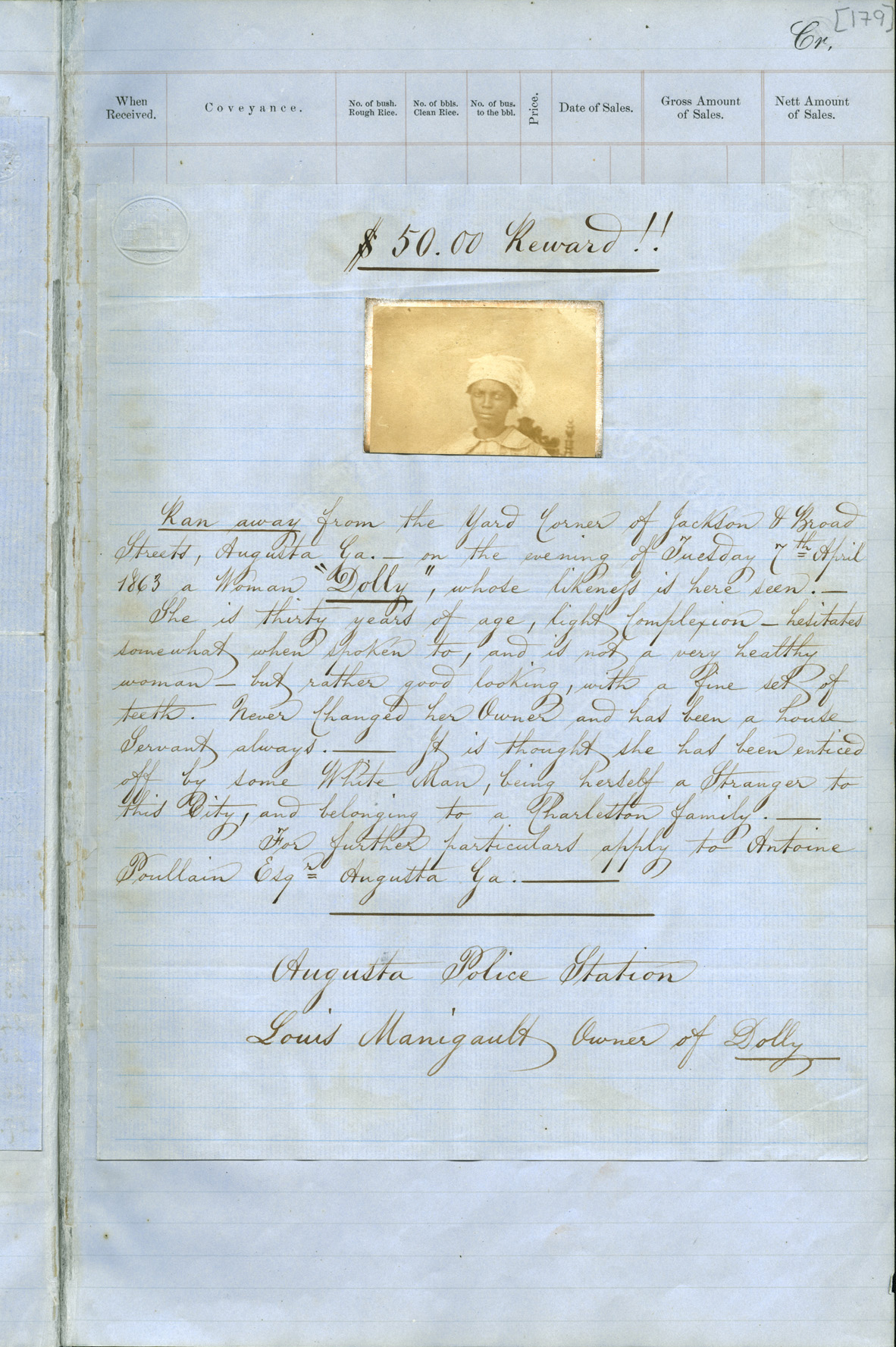

Every slave portrait, no matter how benevolent it seemed, could be used as a tool to police slaves’ movement. This point is illustrated by the case of Dolly, a washer and a cook at the Manigaults’ Silk Hope Plantation, just outside Charleston, and at Gowrie. When the Civil War came, Dolly labored for her mistress Fannie Manigault in safer inland terrain in Augusta, Georgia, but on April 7, 1863, she took flight. Her master Louis quickly responded, circulating at least two fugitive advertisements in Charleston and Augusta. The advertisements laid bare only part of what Louis Manigault felt he knew about Dolly. They described Dolly’s appearance in detail: “thirty years of age,” “light complexion,” “rather good looking, with a fine set of teeth.” Manigault considered one personality trait worth mentioning: she “hesitates somewhat when spoken to.”

The ads also suggested Dolly had been “enticed off by some White Man.” But in private, Manigault and the overseer at Gowrie, William Capers, discussed how they actually suspected Dolly had run off with an enslaved man named Lewis, a bellhop at the L.L. Hotel in Augusta. It is entirely possible, particularly given the mention that Dolly was “rather good looking,” that Manigault had enjoyed or sought sexual relations with Dolly. This could help to explain why he was willing to use various means to catch Dolly but was unwilling to reveal that she had left with an enslaved man.

These means included the use of Dolly’s carte de visite, commonly made by the dozen. Manigault’s innovation in policing tactics reflected an emergent understanding of the draconian possibilities of photography across the country. An 1860 New York Times article suggested that “daguerreotype likenesses of servant girls” could help employers find servants who had stolen from them and absconded. In the South, Manigault had updated fugitive slave ad technology—which had long used generic, crude woodcuts of slaves, often holding a satchel of goods on a stick. His private correspondence, moreover, reveals that he felt the very qualities of portability, transparency, and individuality that made slave photographs windows onto seemingly consenting slaves also made them useful tools to identify fleeing slaves. “Will you be kind enough to show the following to my father who will stick it up at the Police Station + take all necessary steps,” Manigault asked a contact in Charleston. He highlighted how a “similar notice is at the Augusta Police Office, with likeness, which is very important in such cases. This woman left during my absence to the plantation and took with her an ample wardrobe of her own clothes.” Manigault knew that Dolly’s “ample wardrobe” could easily defeat the typical slave ads, which mentioned only what a runaway was wearing on departure. The photograph, however, captured Dolly’s face.

1 From a note attached to the photograph of Hector, Manigault Family Photographs, The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina.↩

Adapted from Exposing Slavery: Photography, Human Bondage, and the Birth of Modern Visual Politics in America by Matthew Fox-Amato. Copyright © 2019 by Oxford University Press and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.