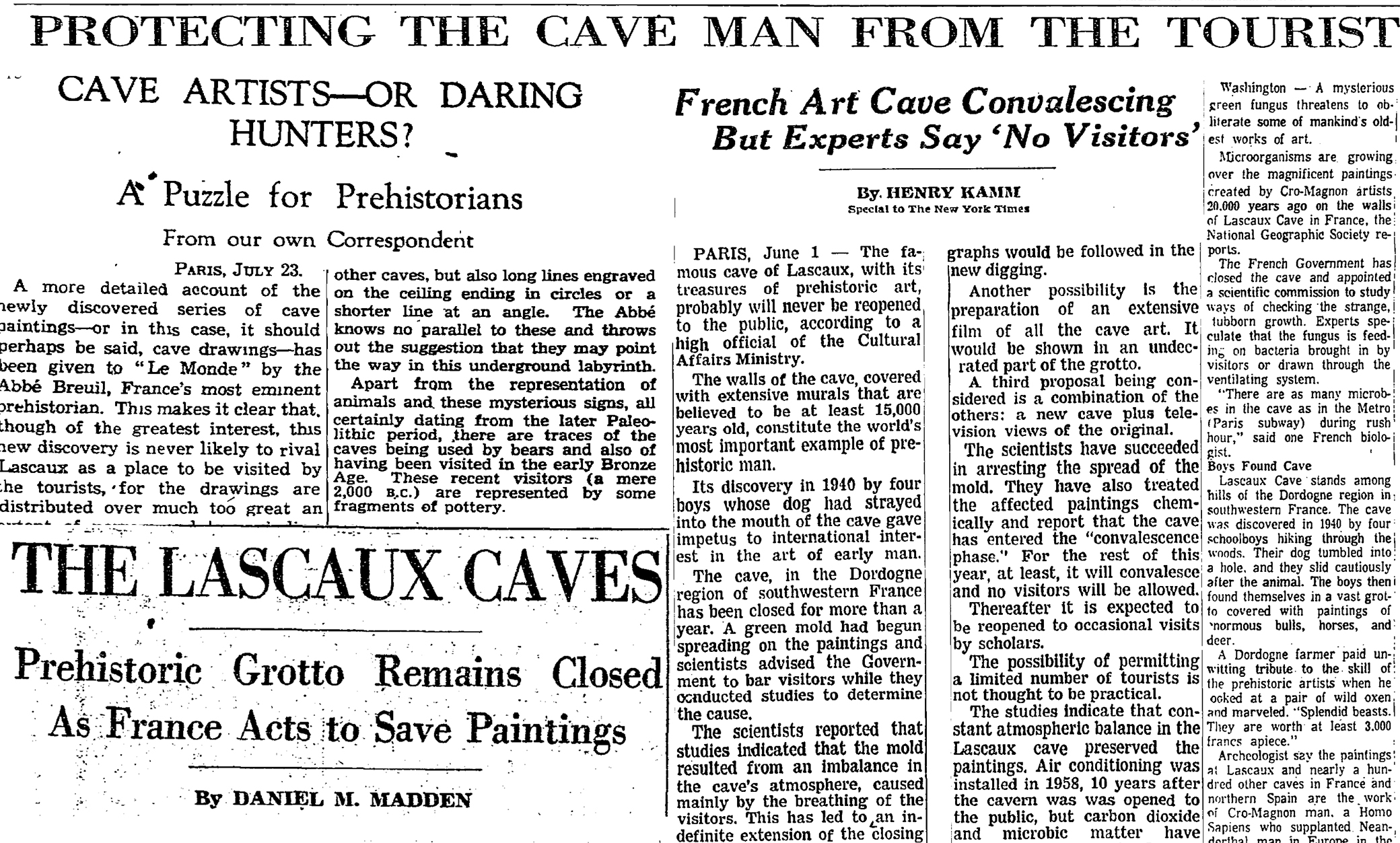

From the Hartford Courant, 1964; the New York Times, 1958 and 1964; and the Guardian, 1956.

The cave paintings of Lascaux were rediscovered on September 12, 1940, seventeen thousand years after their completion, three months after the Nazis marched into Paris, the same month in which German Jews were first ordered to sew yellow stars to their clothing, and four years prior to the bombings of Hamburg and Dresden and Berlin. For most of their existence, a prehistoric landslide sealed them off from the rest of history. A teenage mechanic named Marcel Ravidat was the first modern human being to break the seal. Wandering through the woods outside the French village of Montignac, he noticed a deep hole near an uprooted tree. Inside, using a grease gun as a flashlight, he found perfectly preserved images of stags, bulls, and horses, some of them life-size, some even larger. A few days later, a local specialist confirmed that they had been made by Paleolithic people without agriculture or alphabet.

Ravidat’s timing was oddly perfect. Europe was locked in total war, with both sides insisting that they were saving Western civilization. For France, there could be few more powerful symbols of the rightness of the Allied cause than a hidden gallery of prehistoric art, conveniently located on French soil. Until the end of World War II, resistance fighters used the cave as a hiding place, and when the site was first opened to the public in 1948, the government organized the opening ceremony for July 14, the national day of independence.

Sooner or later, every country plays a version of this game: if an artifact turns up within the country’s borders, then it’s a part of that country’s cultural heritage, even if it was made tens of thousands of years before the country was a country. The people who painted the caves of Lascaux were not, by any fair definition, French or European or Western, but today they are often remembered as the founders of a proud Western tradition they knew nothing about, the humble soil from which Van Gogh and Picasso and Michelangelo sprang.

On the official Lascaux website, you’ll find the cave referred to, more than once, as “The Sistine Chapel of Prehistory.” At least to Western ears, the phrase is strangely soothing, suggesting an unbroken chain of artistic genius linking the Paleolithic to the Renaissance to the present day. The oldest lineages are the noblest, and some historians, afflicted with a nasty case of Eurocentrism, have argued that Lascaux was the site of the earliest visual art ever found, maybe the earliest ever created. Not even close, as it turns out—paintings dating back ten or twenty thousand years earlier have been found in present-day Brazil, Indonesia, and India. But the lie lives on in more than a few textbooks, feeding the myth that Western civilization is the oldest and the best there’s ever been.

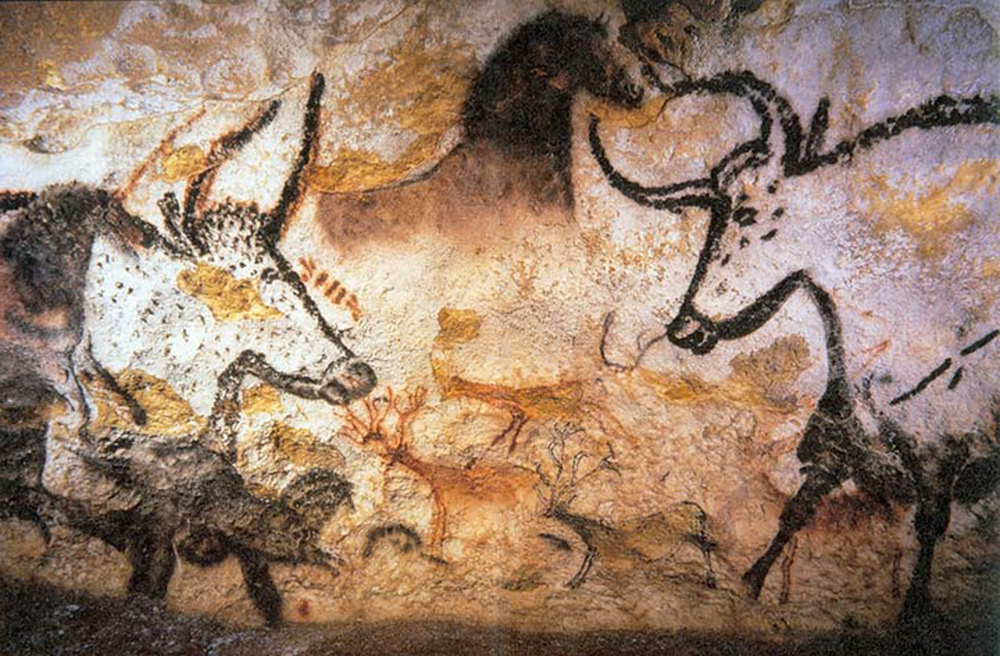

What can be said about the Lascaux caves that isn’t a veiled assessment of ourselves? We know they were painted at some point between 15,000 and 17,000 bc, with pigments scraped from the surrounding land—moist clay for brown and ocher, pulverized berries for red, charred wood for black. We know that the painters led lives that were short and, at least by our standards, brimming with dangers external (wildfires, wild animals) and internal (childbirth, rotting teeth). We know that the painters’ preferred subjects were animals (915 altogether). The Hall of the Bulls, probably the most famous section of Lascaux, is named after its four largest figures, but it also features stags and horses, and bears and bison and galloping rhinoceroses are scattered through the other chambers.

It must have taken the painters a long time to finish the job. They would have needed wooden scaffolds to reach the highest parts of the cave and candles to see what they were painting. Even with hundreds of candles, we can be fairly sure, it would have been impossible for them to step back and admire their work all at once—too many flickering lights and long shadows on the rough walls. It’s not entirely clear that cave art was meant to be looked at after completion; by the same token, it’s possible that cave art wasn’t supposed to be art, at least not art as a twenty-first-century person understands the word.

But rightly or wrongly, the paintings are remembered as “art”: majestic, timeless, and beautiful for the sake of being beautiful. It would be pointless to deny the paintings these qualities, just as it would be impossible not be moved by the sight of a seventeen-foot-long bull curving dizzily around the walls of a prehistoric cave. Images like these achieve a kind of intensity that great modern painters spent their entire careers chasing. After visiting Lascaux in 1948, Picasso, no stranger to bull art himself, declared that artists had learned nothing new in the past ten thousand years.

“Whiggish”—spoken aloud, the word has a pompous air that suggests its definition. Since 1931, the year British historian Herbert Butterfield published The Whig Interpretation of History, it has denoted a certain naive view of human events, a tendency to view the past in present-day terms, like seeing all of English history, from the Magna Carta to the Protestant Reformation to John Locke, as a struggle to create a constitutional monarchy.

That interpretation of English history is, in a word, wrong: there was nothing inevitable about the emergence of Parliament, and England’s rulers and politicians certainly didn’t believe they were working together toward a common goal. But it’s easy for historians to fall into this kind of analysis without realizing their error. For the Whiggish thinker, accidental or otherwise, history becomes a kind of rough draft of modern-day ideas and institutions, notable only for what it prefigures.

If the Whig interpretation of history is seductive, Whig prehistory is all but irresistible. Ever since Ravidat climbed underground with a grease gun, people have viewed Lascaux through the tinted lens of the present, arguing over what the cave says about art or religion or gender or nature with only the vaguest sense for what those things would have meant to prehistoric man. A sign of humanity’s thirst for expression, a cautionary fable for the industrial era, a fertility rite, a requiem, an initiation ceremony—modern attempts to make sense of Lascaux are hazy and contradiction-ridden. Put together, however, they’re something like a miniature intellectual history of the past two centuries, the results of an eight-decade-long inkblot test that thousands of paleontologists, politicians, poets, philosophers, and painters couldn’t resist taking.

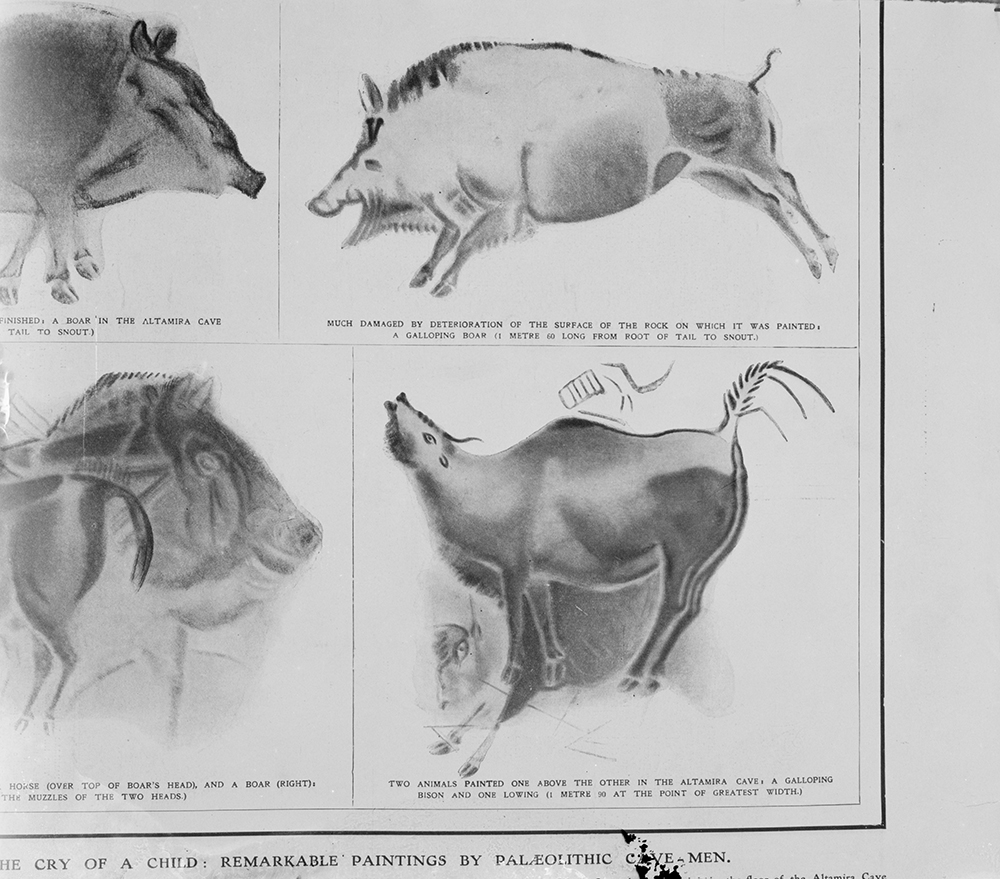

Few people in the past 150-odd years of art history have had better careers than cavemen. The nineteenth-century avant-garde, hungry for an alternative to modern civilization, found one in the prehistoric caves that bored aristocrats were busy uncovering at the time—Altamira in 1879, Font-de-Gaume in 1901, El Castillo in 1903, La Pasiega in 1911. Here was the future, or at least a future, for the arts: stark, fearless, unconcerned with prettiness or realism.

Once you notice it, the Paleolithic is everywhere in the twentieth-century canon. It’s there in the poetry of T.S. Eliot, who finished The Waste Land a few years after visiting Font-de-Gaume; in Max Ernst’s frottage, by which the texture of the wall becomes a part of what’s hanging on it; in Picasso’s bull lithographs (not actual cave art but at least sketched on stone); in French Fauvism and German Expressionism and Wyndham Lewis’ portraits and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Guy Davenport would later call it “the Renaissance of the archaic”—this sudden obsession with mankind’s earliest achievements, slicing through the decadent present like a stone knife.

It takes a lot to pine for the days before flushing toilets. In some ways, the Renaissance of the archaic wasn’t a celebration of prehistory so much as an attack on a modern world the Lascaux painters never knew. For Picasso or Lewis, prehistory became an alternative to history, offering a dose of authenticity that civilization couldn’t match. In the 1950s, the poet and ex-Resistance fighter René Char wrote about the black stags he’d seen on the walls of Lascaux:

You stags have leapt across millennia

From darkness in the rocks to the air’s caresses.

The hunter driving you, the spirit watching you,

How I love their passion, viewed from my wide shore!

“Across millennia”—for Char, the defining trait of cave art is one its creators probably never thought about: timelessness. The survival of the stags and horses at Lascaux was a happy accident; if a landslide hadn’t sealed off the cave, they would have disintegrated within a couple of centuries (the fate, it’s safe to assume, of almost every other prehistoric painting). But the accident enabled twentieth- and twenty-first-century admirers of Lascaux to conceive of it as fresh and mummified at the same time. Walter Benjamin said that antiquity, to a modern, was a ruin. By the same logic, prehistory is an airtight cave.

In 1983 the French government completed a near-identical replica of Lascaux, located two hundred meters from the entrance of the original cave. This seemed to be the only way to solve the problem of contamination, the inevitable result of germs, moisture, and carbon dioxide smuggled by tourists into a site that, until recently, had been sealed off from the elements. In the coming decades, Lascaux II was succeeded by Lascaux III and then Lascaux IV, the latest in the beloved franchise. The faux cave was created with a 3-D laser scanner; it’s housed in a big, slick museum designed by an international architectural firm. Lascaux IV’s hours are nine am to seven pm, tickets for adults cost sixteen euros, and a recommended visit lasts between two and three hours. As of March 2019, Lascaux IV was rated the second-best thing to do in Montignac on TripAdvisor. From the online reviewers:

The caves of prehistoric art of France are world treasures that everyone should experience.

The gift shop isn’t anywhere near as good as the Chauvet Cave gift shop, but that’s a small complaint.

The replica is absolutely perfect. At first I was worried it would be tacky, but they have it presented in such a way that you really forget you’re in a replica. And the self-guided exhibit afterwards was really excellent to get up close and see the detail. I can’t recommend it highly enough. I rented a car and drove from Sarlat. While the scenery was nice, it was quite a twisting route on narrow roads. I would have been completely lost if I hadn’t rented a GPS at the last moment. In retrospect booking a bus tour might have been a good option.

Overall a brilliant experience that surpassed my expectations.

This was the highlight of my whole week.

Go as early as possible.

There was a time when you couldn’t talk about Lascaux, or cave paintings in general, without talking about a French abbot, artist, archaeologist, and Whiggish anthropologist named Henri Breuil. He was born in 1877, shortly before the rediscovery of the Altamira caves that would consume much of his professional life. As a professor of prehistoric ethnology in Paris in the 1920s, he developed the theory that cave paintings were the remnants of a religious ceremony. Paleolithic hunters would paint animals before going out to hunt them; by controlling their images first, they believed they could control their bodies later.

Breuil made important contributions to his field. He was also consistently wrong about the works he studied. On an expedition to Namibia in the 1950s he discovered a beautiful image of a woman painted on the side of a mountain. Rather than accept that this image could have been made by black people, he tried to argue that it was the work of ancient Mediterranean artists who had traveled thousands of miles across the Sahara, leaving no trace of their journey. Visits to Lascaux strengthened his confidence in claiming that the cave’s artworks were part of a pre-hunt ritual—despite the fact that reindeer, Paleolithic locals’ primary food source, are never pictured.

Gradually, other theories replaced Breuil’s, many of them proposed by French specialists funded by the French Ministry of Culture. The paintings were meant to celebrate the end of a great hunt. The paintings were meant to honor the spirits of animals, which early human beings worshipped as gods. The paintings expressed remorse. The paintings were part of an initiation ceremony. The paintings expressed triumph. That European cave paintings, whatever they were for, were the world’s oldest went almost without saying. (The 2018 discovery, by Maxime Aubert, Pindi Setiawan, and Adhi Agus Oktaviana, that Indonesian cave paintings are at least forty thousand years old—i.e., older than any paintings found on Western soil—was met with polite surprise. It now seems fairly obvious that the rediscovery of so many cave paintings in Europe in the past two hundred years does not prove that prehistoric Europeans invented art, only that modern Europeans have been blessed with an extraordinary amount of time and money to spend digging up their own land.)

The most famous painting in Lascaux is called the “Dead Man,” or the “Bird Man,” or simply the “Shaft Painting,” after the tall, narrow area where it was found. It’s also the only painting in Lascaux to feature a human being, if a man with the head of a bird counts as human.

The bird man is lying next to a bison, and both figures appear to be dead or dying. The bison has been pierced with a spear; the bird man’s spear rests, broken, near his feet. The painting is, quite appropriately, all about “shafts”—not only the two weapons but also the short stick, pictured nearby, with a bird on top and, most perplexingly of all, the bird man’s erection, pointing straight at the bison’s heart.

Every part of the Shaft Painting, cries out, to borrow Adorno’s famous line about Kafka, “Interpret me.” In this sense, it’s quite different from Lascaux’s other, more brazenly literal images, to the point where some archaeologists suspect it was created much earlier or later than its neighbors. The writer Georges Bataille, one of postwar Europe’s most dedicated students of Lascaux, found the bird man too “schematic,” even as it reinforced his theories about the unity of Paleolithic man and animal.

To the Freudian, the Shaft Painting is about achieving sexual maturity. To the existentialist, it’s about the human condition before the alienation of modern life set in. To the feminist, it’s about the origins of patriarchy. To the structural anthropologist, it’s about religion—and so on, the ingenuity and validity of each of these theories as obvious as their insufficiency. In 2012 the artist Trevor Paglen offered an unmistakably twenty-first-century take: “When I look at it I see a painting of a humanoid who has just inaugurated the greatest mass extinction that the world has ever seen and is sexually excited by that. I sometimes think that the artist who painted that scene meant it as a confession to the future.”

Paglen’s theory probably isn’t the most accurate interpretation of Lascaux, and it’s not entirely clear he buys it himself. (Why would the agent of mass extinction have a bird’s head?) But it has a claim to being the most honest; when discussing the prehistory of Homo sapiens, often the best we can do is say, “When I look at it I see…”

Paglen’s remarks sum up the discourse surrounding cave painting in another sense as well. In 1963, fifteen years after opening Lascaux to tourists, the French government closed it again. The paintings were drowning in mold, courtesy of the thousands who visited Lascaux every day and made it a little uglier for those who came later. Since the 1960s, an enormous amount of money and brainpower has been sacrificed to protect Lascaux from its admirers—all for the sake of images that probably were never meant to last more than a few years, let alone seventeen millennia. Nobody can agree on what the paintings were for, but everyone seems to acknowledge that they should be protected at all costs—and so the discourse surrounding the cave has inched away from the essential What was it for? and toward the existential How do we hang on to it?

That the 1960s also saw the birth of the modern environmental movement is no coincidence. Setting aside the vast difference in scale, the debate about the future of Lascaux Cave is the debate about the future of the planet. The forces that Lascaux’s preservationists were fighting—carbon dioxide, rising temperature, newly resilient microbes—quickly turned out to be the same forces demolishing the world’s ecosystems. In both cases, of course, the underlying culprit was the same. Substitute “Lascaux” for “Earth” in the transcripts of a 2009 symposium on the cave and they read like a survey of environmentalist rhetoric, ranging from moderation to fatalism:

We have never had a static and stable equilibrium, on the contrary there have always been changes in certain climatic parameters.

Any adverse effect on the works of art in the cave, whatever it may be, is sorely felt by those who love it, i.e., all of us. However, we are far from the cataclysmic announcements we may have heard or read. No, the frescoes of Lascaux are not “condemned” and the cave is not in “danger of death”!

Lascaux is the tragic illustration of human errors, when fluctuating age-old equilibrium is suddenly broken.

The symposium, organized by the French Ministry of Culture and Communication, was occasioned by the arrival of an especially nasty fungus called Fusarium solani. The fungus is believed to have been spread to the walls of the cave by workmen installing (fate has a sick sense of humor) a filtration system designed to keep the paintings in perfect condition.

Lascaux’s recent history is riddled with these humiliations, little reminders that some of the world’s most powerful people have only the vaguest sense of what they’re doing. It’s doubtful that the ministry would have addressed the mold crisis so quickly if the UNESCO committee hadn’t threatened to add Lascaux to its list of endangered sites (imagine the headlines: cultural capital of the world can’t care for its own culture). But in other ways the Lascaux preservation movement has been a model of level-headed international cooperation. There are no cave climate-change deniers (or, on the other extreme, ecoterrorists trying to dynamite the cave back into airtightness). When France hosted its symposium and invited specialists from around the world, no countries boycotted the event. There are no corporations with incentives to ignore the situation at Lascaux or corporate-sponsored lobbyists sowing doubt among the powerful. Because the beauty of the cave can’t really be exploited, nobody has second thoughts about preserving it.

Even if the Lascaux paintings evaporated tomorrow, they would live on in at least one other form. Paglen included a photograph of the Shaft Scene in The Last Pictures, a work of art so grandiose it starts to sound satirical before going back to grandiose again. The Shaft Scene and ninety-nine other images (among them a still from a Japanese science fiction extravaganza and a shot of Leon Trotsky’s brain) were etched onto a gold-plated silicon disc. The disc was placed inside the EchoStar XVI communications satellite and launched into space from Kazakhstan in October 2012. At the moment it’s hovering 24,000 miles above the Earth’s surface, where it will stay until someone discovers it or until it burns up, whichever comes first. When asked to describe the work, Paglen used the phrase “modern-day cave painting”—a Space Age Lascaux, waiting to be oohed and ahhed over by whatever kind of life survives the present.

That analogy fairly reeks of Whiggishness—Paleolithic art reimagined as a rough draft of Paglen’s project. There’s no reason to believe that the people who decorated Lascaux daydreamed about a distant future in which their descendants would admire their handiwork, and there are more than a few reasons to think they didn’t. But there’s another way in which The Last Pictures does bear comparison to the paintings of Lascaux: billions and billions of years from now, it is likely to reveal just as little about the beings who made it and just as much about the ones who find it.