This past summer, as antiracist protestors marched through Brussels—past Avenue du Congo, Rue des Colonies, and so on—the Belgian Federal Parliament assembled a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to formally address the country’s colonial legacy. “Up till now, Belgium has not conducted a reflection on its colonial past,” said commission chair Wouter De Vriendt. “It still divides our society.” A key point of contention is King Leopold II, who ruled the Congo Free State as a personal fiefdom from 1885 to 1908, leading to the deaths of an estimated ten million Congolese people. Many Belgians hope to preserve the various statues of the monarch that still preside over the country’s public squares and seafront vistas.

These monuments are mostly standard imperial tributes, interchangeable give or take a horse or a kneeling Congolese subject. The parliamentary commission might propose to take the statues down or to melt them into depictions of less monstrous Belgians. For the most part, the artists who sculpted these works are dead and unable to object. The latest Leopold II statue, however, was created only in 1998, the center of a sculpture fountain outside Brussels. Its sculptor, Tom Frantzen, noted for his lighthearted public art—jolly renderings of Belgian icons like Hergé and Jacques Brel—is now in his mid-sixties. He has become caught in a debate that barely existed in Belgium in the 1990s, when it was commonplace to praise King Leopold II for his avenues and arboretums, as if his civic works were distinct from the exploitative regime that financed them.

Frantzen, who is white, insists that the statue should remain on view, but not for the customary reasons. In 2018, twenty years after the statue’s installation, he claimed that his bust of the king is actually an anticolonial satire—and had been all along. “This group of statues is the only anticolonial statue in our country and may be regarded as unique,” he announced, eventually triggering an inquiry into why, for the previous two decades, there had been no public record of this political stance.

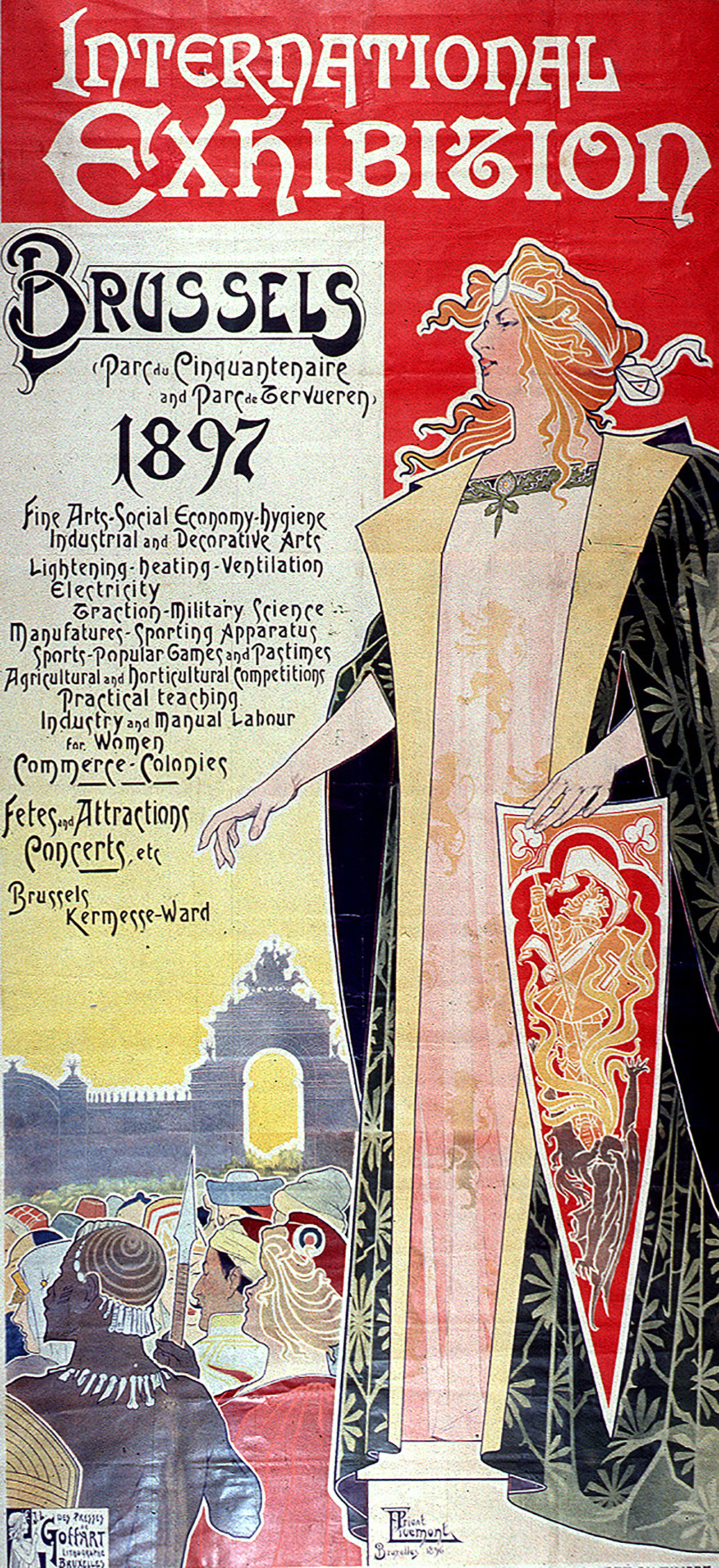

The statue sits on the grand lawn of a former colonial museum outside Brussels, known for its taxidermy animals and looted art. Local heritage associations installed the artwork for the centennial of the 1897 Colonial Exhibition, a fair held on the same grounds to promote Leopold II’s colonial project to a reluctant Belgian public. The resulting commemorative bust—surrounded by bronze animals and a trio of “African warriors”—resembles any other statue of the king, with his recognizable aquiline nose and rectangular beard.

The nearby museum, the Royal Museum for Central Africa, founded in 1898, was rebranded as the Africa Museum in 2018, after an exhaustive renovation meant to address its colonial past. It was at this point that Frantzen offered an artist statement (the sculpture’s first), explaining his supposed satire. The elephant diverts his gaze away from the monarch, signaling his rejection of “the ivory looting with which Leopold II shamelessly enriched himself,” while the lion’s turned head demonstrates that “he despises the king’s actions, and the king’s people who violated his habitat.” The warriors’ peg legs apparently serve as a comment on colonial violence: “Note also that the strong warriors have chopped-off feet,” he declared, “a direct reference to the least beautiful story of colonization.” (Amputated hands were a hallmark of the Belgian colonial project, collected by soldiers as justification for used bullets.) The title, The Congo, I Presume, was more than a vague play on the nineteenth-century colonial catchphrase “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”; it referred to “the disdain the king displayed toward the Congolese people,” he later explained.

This anticolonial narrative didn’t meet with any public resistance at first. The Brussels-based newspaper Le Soir reported on Frantzen’s statement without comment; an online inventory of Belgian monuments registered the artwork as “a satirical commemoration of the 1897 Colonial Exhibition.” The Africa Museum published Frantzen’s text on its website and made it accessible via a QR code next to the monument. Still, not everyone accepted the about-face.

The style of The Congo, I Presume is muted compared to a typical Frantzen statue. His other sculptures are often exaggerated and theatrical, acting out childish hijinks in the spirit of zwanze, a cheeky Bruxellois brand of humor. While the animals are rendered with cartoonish contours similar to Frantzen’s other work, Leopold II receives a traditional, dignified treatment. It’s hard to imagine that a passerby would pick up on the work’s supposed anticolonial message, particularly given the regal setting. On the other side of the lawn, the museum’s Beaux-Arts palace still carries the Builder King’s monogram in at least forty-five places; the estate and even the tramway connecting the town to the capital were directly financed by the exploitative rubber and ivory trade established by Leopold II. At most, a generous visitor might note that the composition elevates a Black person for once, with the “African warriors,” outfitted with spears and feathered headdresses, positioned above a European colonizer.

Although Frantzen’s revised account of the statue fit with the museum’s newly rehabilitated image, museum director general Guido Gryseels was skeptical. “Frankly, I don’t know what to think of it,” he told me. When Gryseels started working at the museum in 2001, its displays hadn’t evolved since he had first visited it as a child, over a half century earlier. He had always considered The Congo, I Presume a holdover of this uncritical approach, yet another statue cast from the same racist stereotypes. In summer 2020 Gryseels finally checked his memory against the archives. “I read his brochure from 1998,” he reported, “and there is a totally different interpretation than the interpretation he gives now.”

The unveiling ceremony was indeed steeped in colonial nostalgia. The leopard-print flyer celebrated the civic works that the king had bestowed upon the nearby town of Tervuren. Reverence for the king was overt, if tempered with caveats. “It is true that Leopold’s Congo policy was decidedly controversial, especially in the light of future events,” read the press release. “But it is also undeniable that the Congo became a Belgian colony, and that the relations between the two countries have always been close.” After speeches praising the monarch, the guests—including representatives from the government and the royal family—retired to the museum rotunda, where a brass quartet played beneath artworks depicting scenes such as Belgium Bringing Security to the Congo or Belgium Bringing Well-Being to the Congo.

Newspaper clippings from the era likewise conflict with Frantzen’s account. Le Soir reported that Frantzen himself initiated the project: “The sculptor Tom Frantzen, listening to the djembe drum and the savanna radio, wanted to bring his contribution to the centennial of the Colonial Exhibition of 1897.” (He then “took his machete” to administrative hurdles.) Elsewhere Frantzen praised the visual symmetry between his work and the 1897 fair’s reconstructed villages, where hundreds of Congolese people were forced to perform behind barriers and signs that read do not feed the congolese.

COMRAF, a Congolese diaspora organization founded in 2004 to advise the museum, was also unconvinced by Frantzen’s new artist statement. “In the early 2000s,” explained the organization’s president, Billy Kalonji, “the word decolonize wasn’t even mentioned.” The museum has only started to correct for close to a century of silence on its colonial origins—a situation historian Adam Hochschild has compared to “a huge museum of Jewish art and culture in Berlin that made no mention of the Holocaust”—in the past decade, thanks in part to COMRAF. Its organizers have continually petitioned for interventions, such as recognition for the Congolese who died in the 1897 Exhibition, despite resistance from the museum’s overwhelmingly white staff. Much like the museum, the statue doesn’t merit a sweepingly reparative reputation either, Kalonji said. “It can’t be a so-called decolonial monument without the inclusion of the people concerned,” he argued, referring to the community that Frantzen included only as bronze flamingos. (The migratory birds supposedly represent today’s Congolese diaspora.)

As a public monument, the statue is not technically the Africa Museum’s responsibility; it falls under the jurisdiction of the Belgian Buildings Agency. But in July 2020, amid local and international protests against racism and an atmosphere of heightened scrutiny, the museum tacked a short note onto Frantzen’s text. It states that, at the time of the inauguration in 1998, “it was clear [the statue] had been placed there in honor of King Leopold II.” The note is cautious, avoiding any explicit accusations. All the same, it offended Frantzen, who told me the intervention was “absolutely malicious.”

No one but Frantzen can be sure of his original intentions. For all the paint-by-numbers symbolism, there are a few arguments in his defense. His magnum opus, The Waaienberg Trails, a fantastical sculpture garden outside Tervuren, speaks to a similar kind of chaotic parody, even though its Boschian cortege—complete with robots, Trojan horses, and a caricature of Angela Merkel as the Statue of Liberty in a suicide vest—was created years after The Congo, I Presume. The inclusion of severed legs is also unsettling, and difficult to dismiss. Frantzen claims that he “had to move heaven and earth to get permission to depict the black warriors with lopped-off feet.” It certainly evokes some kind of brutality, even if the details are inconsistent with the actual colonial practice of amputation, which concerned hands rather than feet.

Frantzen recently proposed changing the statue, conceding, if only indirectly, that the “satirical anticolonial message does not seem to be clear enough for certain people.” Titled The Fall of the King, the new intervention would throw the monarch from his pedestal, copying what activists have been trying to do for decades, long before it was fashionable. In Frantzen’s version, the king would remain awkwardly on display, suspended at a diagonal mid-fall, his stiff beard angled skyward.

In the end, whether Frantzen’s anticolonial stance is genuine or just a revisionist gloss, the harm is the same. It obscures the reality that just twenty years ago, it was acceptable to gather on a mild spring day to applaud the father of Belgian colonialism—a fact that’s all the more urgent given the Africa Museum’s outsize role in educating the public. A field trip to the museum—which over half of all Belgians have visited—serves as a primary lesson in colonial history for thousands of schoolchildren every year.

In 2018 the most offensive statues in the museum’s collection were relegated to an underground gallery, a mea culpa basement where visitors can shake their heads at all the racist tropes. It’s a superficial and self-congratulatory exhibit, but it still manages, as Gryseels puts it, to remind Belgians of “how we used to see Africa.” The sketches for The Fall of the King similarly attest to the impulse to explain away one’s failures and attribute the values of the present too generously to the past—a challenge for any historical reckoning, particularly the kind that the Belgian Parliament now hopes to undertake.

In the meantime, the sculpture fountain remains on the lawn, framed by stately topiary and historical plaques with perfunctory mentions of the estate’s violent origins, including its fin-de-siècle human zoos. Lately the bust of King Leopold II has fallen into a state of disrepair. Frantzen suspects that the lack of upkeep is “a pretext to remove the sculpture collection,” explaining that the government has the right to remove artwork by a living artist if it’s repeatedly vandalized. The shallow water no longer conceals the concrete blocks beneath the bronze figures; spray-painted in bright red, “FDP,” the French acronym for “son of a bitch,” still stains the king’s pedestal.