Disk brooches, c. 600. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Joseph Pulitzer bequest, 1987.

To understand the earliest Anglo-Saxon kings, it is perhaps best to begin with a story about their contemporaries in Scandinavia. Around the start of the sixth century there was a Danish king called Hrothgar, who ruled for many years with great success but was brought low by a monster that repeatedly attacked his mead hall and massacred all his men. Eventually, after twelve years of despair and devastation, he and his people were saved by a young hero from the neighboring land of the Geats, who defeated and killed the monster with his bare hands, and for an encore went on to dispatch its vengeful mother, who lurked in a lair at the bottom of a lake. Such was the hero’s amazing prowess that he later became king of the Geats, ruled for fifty years, and died in old age defending his people against a dragon.

As a historical source, this story has the disadvantage of being completely made up—the monsters and the dragon are something of a giveaway. The above is a very bald summary of a long poem, known since at least the eighteenth century by the name of its heroic protagonist, Beowulf. Although set in Scandinavia, it is written in Old English by an anonymous author. It survives in only a single manuscript, badly damaged by a fire in 1731. From the style of its script we can discern that it was written around the year 1000, but most historians think that the poem itself was composed considerably earlier. Based on its content, it cannot have been written before the middle of the seventh century, and despite lots of robust academic debate in recent decades, the majority view remains that it is probably a product of the eighth century. Given that lay literacy at that time was highly restricted, the likelihood is that it was the work of a priest or a monk.

Early students of Beowulf were disappointed that it was preoccupied with monsters and said almost nothing about real historical events or people. Its only apparent link to reality is Beowulf’s uncle, King Hygelac, who has been tentatively identified as the man who invaded Frisia around 523, which is how we deduce that the poem is probably set in the sixth century. But these early scholars rather missed the wood for the trees, because while Beowulf is all but useless for reconstructing the politics of sixth-century Scandinavia, it is peerless in illuminating the society of the earliest Anglo-Saxon kings and their subjects. It vividly brings to life a world in which kings dwell in great wooden halls, feasting with their followers, drinking mead, and listening to poets harping about the heroes of old; an era of restless warrior bands in search of adventure; and wandering royal exiles, hoping one day to win back their ancestral thrones.

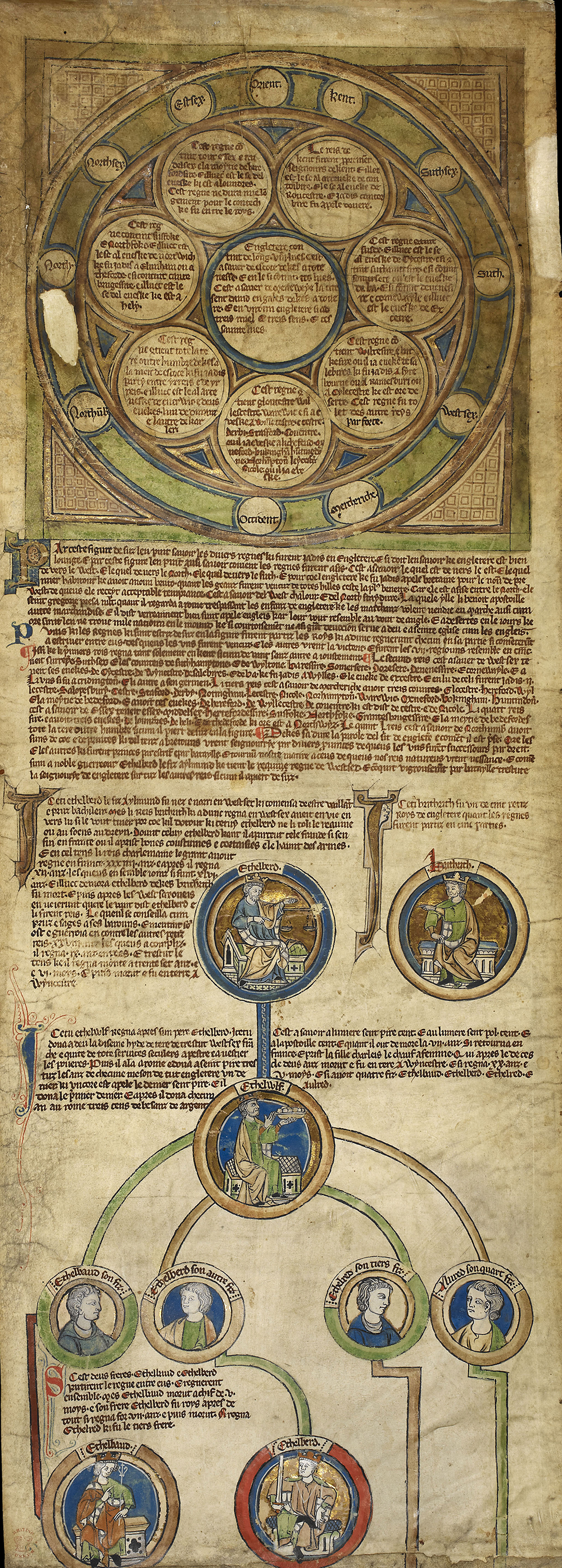

Beowulf is a much better guide to the earliest Anglo-Saxon kings than some seemingly more sober and bona fide sources. Take, for example, Henry of Huntingdon, who wrote The History of the English in the early twelfth century. “Now when the Saxons subjected the land to themselves,” Henry tells us, “they established seven kings, and imposed names of their own choice on the kingdoms.” He goes on to list these kingdoms in what he implies was their order of creation: Kent, Sussex, Wessex, Essex, East Anglia, Mercia, and Northumbria.

It is hard to overstate the enduring impact of this statement. Henry’s confident declaration that there were originally seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms quickly became an established fact and gave rise in the sixteenth century to the word heptarchy, a term that still finds its way into school curriculums today, despite academics suggesting for the past half century that it should be given a decent burial. Their reason for doing so is that Henry’s assertion rests on no authority at all—he simply listed the more prominent kingdoms he found in his early sources.

Another source on which Henry of Huntingdon drew heavily was the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle—or Chronicles, as some historians prefer. These were initially compiled at the end of the ninth century by scholars working at the court of Alfred the Great and relate the history of Alfred’s kingdom—Wessex—and its neighbors from the earliest times. The compilers presumably drew on older annals and sources that are now lost, for some of the information they record is demonstrably true. Among the entries for the fifth century, for instance, we find dates for the accession of popes, emperors, and bishops that are tolerably accurate. The Chronicle gives the impression of being a credible source even for the earliest period, and for centuries historians were inclined to treat it as such.

It also provides stories about the foundation of other kingdoms. Sussex, we are told, was founded in 477 when Ælle landed with his three sons in three ships, killed many Britons, and drove the survivors into the woods. Wessex, meanwhile, was apparently founded by Cerdic and Cynric, a father-and-son team who beat the Britons, having also arrived in three ships, or possibly five—the Chronicle is confused on this point and has them arriving twice, in both 495 and 514.

But the narratives that suggest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were being founded from the middle of the fifth century are flatly contradicted by the archaeological record. When we look at the remains of early settlements, for instance, what we find is all relatively modest. Buildings are either fairly humble halls that look to be residences or else an even more basic type, constructed over a shallow pit, and hence known to archaeologists as sunken-featured buildings; these were probably used as workshops or stores. There is nothing on such sites to suggest much in the way of social differentiation.

It seems that the earliest Anglo-Saxon settlers had set themselves up as free, independent farmers. They took—or were granted by whoever was in charge—enough land to support their family. This family would have lots of dependents to help work the land who were not free—slaves, probably in many cases Britons who had remained in situ or else had been rounded up by their new masters. Such divisions of status seem to be reflected in the earliest cemeteries, in which around half of all adult males were buried with some form of weapon. Since in barbarian societies the bearing of arms was equated with freedom, it seems likely that these were the graves of freemen, or ceorls. By implication, those males buried without weapons would have been their slaves.

In the latter part of the sixth century, several changes happen at once. From around 570 there is a sudden and dramatic drop in the number of furnished burials, both male and female—enough to suppose that the practice had been deliberately restricted. At the same time, we find a minority of individuals being interred in extremely ostentatious ways, buried with extravagant quantities of costly items under giant mounds of earth. Such barrows burials had been common enough in Bronze Age Britain but had seldom been carried out in the intervening 1,500 years. Their reintroduction in the late sixth century signaled the emergence of an elite determined to advertise its superiority. When we look at the building record, there is a sudden desire on the part of some to build on a much grander scale, constructing dwellings that dwarfed the modest homes of others.

These changes in the archaeological record accord well with the evidence of place names. Among the commonest types of Anglo-Saxon place names are those ending in -ing or -ingham, elements which mean “the people of” and “the settlement of the people of.” A place name like Reading, for example, means “Reada’s people” in Old English, and similarly Wokingham means “the settlement of Wocca’s people.” In the nineteenth century, and for a long time into the twentieth, scholars were happy to believe that these names had been introduced into the landscape by the earliest Saxon settlers, and that men like Reada and Wocca must simply have been among the first off the boats. It has since been shown, however, that this was an unfounded assumption, because such place names do not coincide with the earliest archaeological evidence of settlement. It now seems likely that the first examples of -ing and -ingham names date to the late sixth century—the same moment we see signs of rapidly rising elites.

This timing might alter the way we think about such names. There is a tendency to picture places ending in -ing as rather cozy communities, living together because of bonds of kinship—little more than extended families. Beowulf begins with a brief history of King Hrothgar’s people, who are called the Scyldings, after their found father, Scyld, and it assures us how much they loved their leaders past and present. But it also makes clear that these leaders were lords, and the way they had achieved their dominance was far from benign. Scyld, we are told, had started life as a foundling but rose to greatness by robbing the halls of others and laying fear upon them, forcing them to pay tribute. We may suspect that something similar was occurring in late sixth-century Britain, and that men like Reada and Wocca were not necessarily benevolent father figures, but rather men with strong right arms, violent proclivities, and boundless greed, asserting control over others, demanding tribute in the form of goods and services. Ceorls who had previously been independent, farming their single hides of land, lords of their own little communities of family and slaves, now found themselves bound to contribute to the upkeep of one particular individual or family that was lording it above the rest.

If this model is correct, it meant that originally kingship was open to anyone with enough ambition and muscle—even a foundling like Scyld could quickly create a lordship that covered a large territory. And it implies that initially there may have been quite a lot of kingdoms—a good many more than the seven immortalized by Henry of Huntingdon in the twelfth century.

The most common assumption is that all kingdoms probably began as such small-scale affairs, and that some had grown larger by bullying others into a state of dependence. Having secured the submission of his neighbors, an ambitious warlord could call upon them to fight in his ranks, enabling him to take on bigger contenders, until eventually he established his supremacy over a wide region. At what stage such a man might start styling himself as “king” must have varied from case to case. The modern word derives from the Old English cyning, meaning something like “son of the kin.”

It is impossible to say for certain why kings suddenly emerged in the later decades of the sixth century, but the middle decades had been notably catastrophic. Trouble began in 536, when a number of writers noted that something was very wrong with the weather. “During the whole year,” said the Byzantine historian Procopius, “the sun gave forth its light without brightness…it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear.” Even the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, generally unreliable as it is for the sixth century, noted two eclipses around this time.

It was a “dust veil” event caused by volcanic eruptions, first detected in the data in the early 1980s. Scientists have only recently pinpointed the culprit as a volcano that erupted in Iceland in 536, and then again in 540 and 547. On each occasion it spewed enough ash into the sky to obscure the sun across the whole of the northern hemisphere, causing a dramatic drop in temperatures: recent analysis has identified 536–45 as the coldest decade in the past two thousand years.

The consequences were obviously calamitous: crops failed everywhere and famine swiftly followed. “Failure of bread,” wrote an Irish annalist in 536, and again in 539. After the famine came bubonic plague. It began in the east, devastating Constantinople in 541, spreading to the western Mediterranean in 542, and eventually reaching Ireland in 544, where it must have torn through a population already weak from hunger. It is extremely unlikely, as some have suggested, that this plague did not also spread to Britain. We can reasonably infer, in spite of the absence of documentary evidence, that the Anglo-Saxon communities in the east of Britain must also have been affected. Even if, by some unlikely fluke, they managed to avoid the worst ravages of the disease, they would still have faced the same climate downturn and famine during these terrible decades: you cannot dodge a dust-veil event.

All over the British Isles, across Europe and beyond, populations must have been devastated in the middle years of the sixth century. In Ireland the calamities kept on coming until the mid-570s, with the earlier plague followed by a wave of further epidemics, including smallpox. The unknown factor is how quickly these societies recovered from what one chronicler called “the great mortality.” The southwest of Britain appears to have been hit very hard and to have remained depopulated for decades, possibly centuries. Other British areas, such as the northwest, seem to have recovered quite quickly, to judge from the archaeological record. Precisely how the Anglo-Saxon communities to the east were affected will probably never be known, but it is hard not to imagine that the shocks of the mid-sixth century could have caused society to be severely shaken and radically reshaped. Acute shortages of food must have led to increased violence, with desperate communities raiding each other.

Devastated survivors may have been willing to surrender their independence and submit to the rule of others if that was the only way of guaranteeing their sustenance. (The word lord derives from the Old English hlaford, meaning “loaf-guardian,” or “bread-giver.”) Amid all the death, violence, and chaos, there must have been a few individuals who emerged as winners and were able to turn the desperation of others to their own advantage.

Adapted from The Anglo-Saxons: A History of the Beginnings of England: 400–1066 by Marc Morris, published by Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2021 by Marc Morris. All rights reserved.