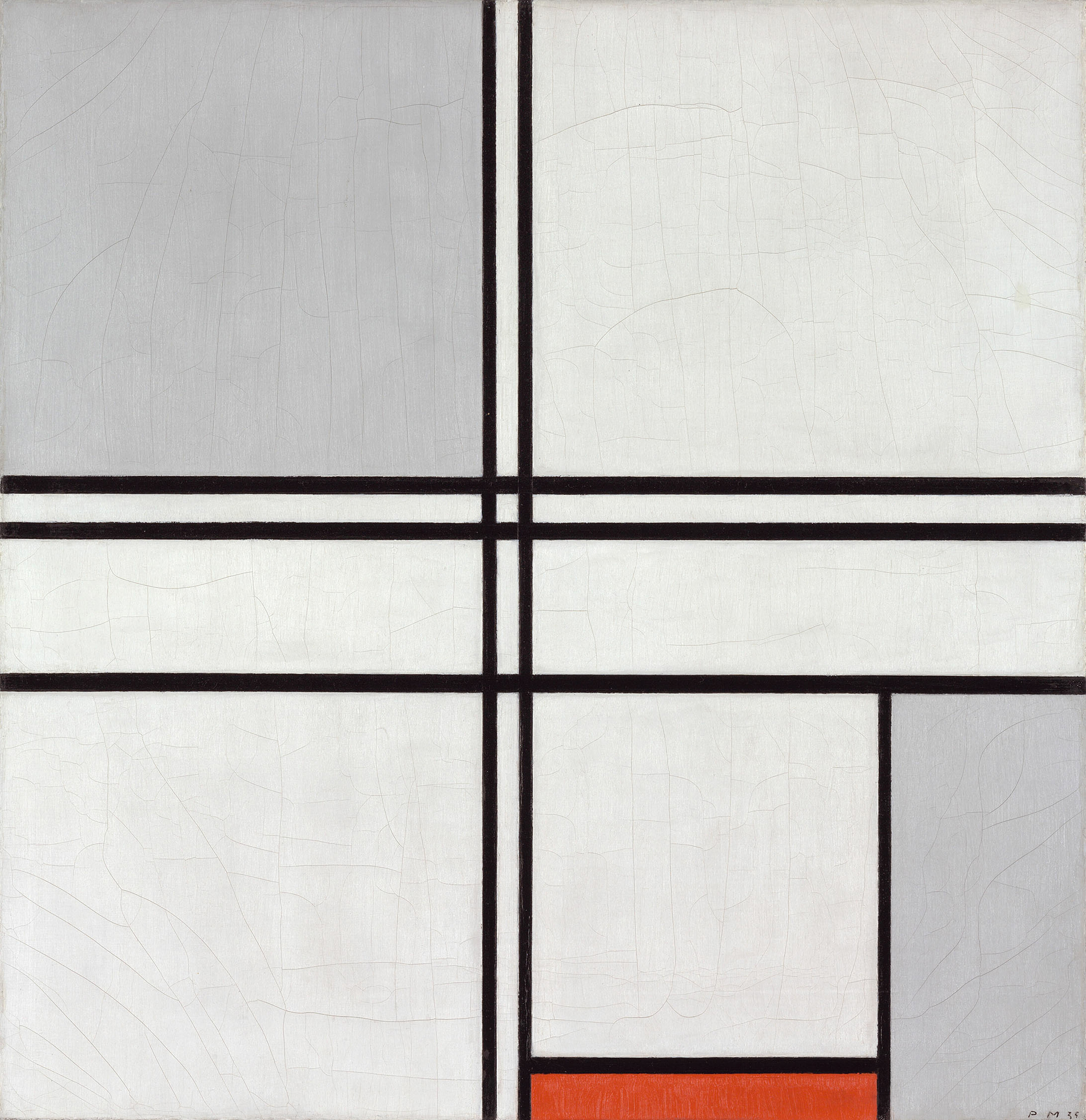

Composition (No. 1) Gray-Red, by Piet Mondrian, 1935. Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Mrs. Gilbert W. Chapman.

Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the history of best sellers, exploring the circumstances that might inspire thousands to gravitate toward the same book and revisiting well-loved works from the past that, due to a variety of circumstances, vanished from the conversation after they peaked on the charts. To read more about the project and explore the other entries in the series, click here.

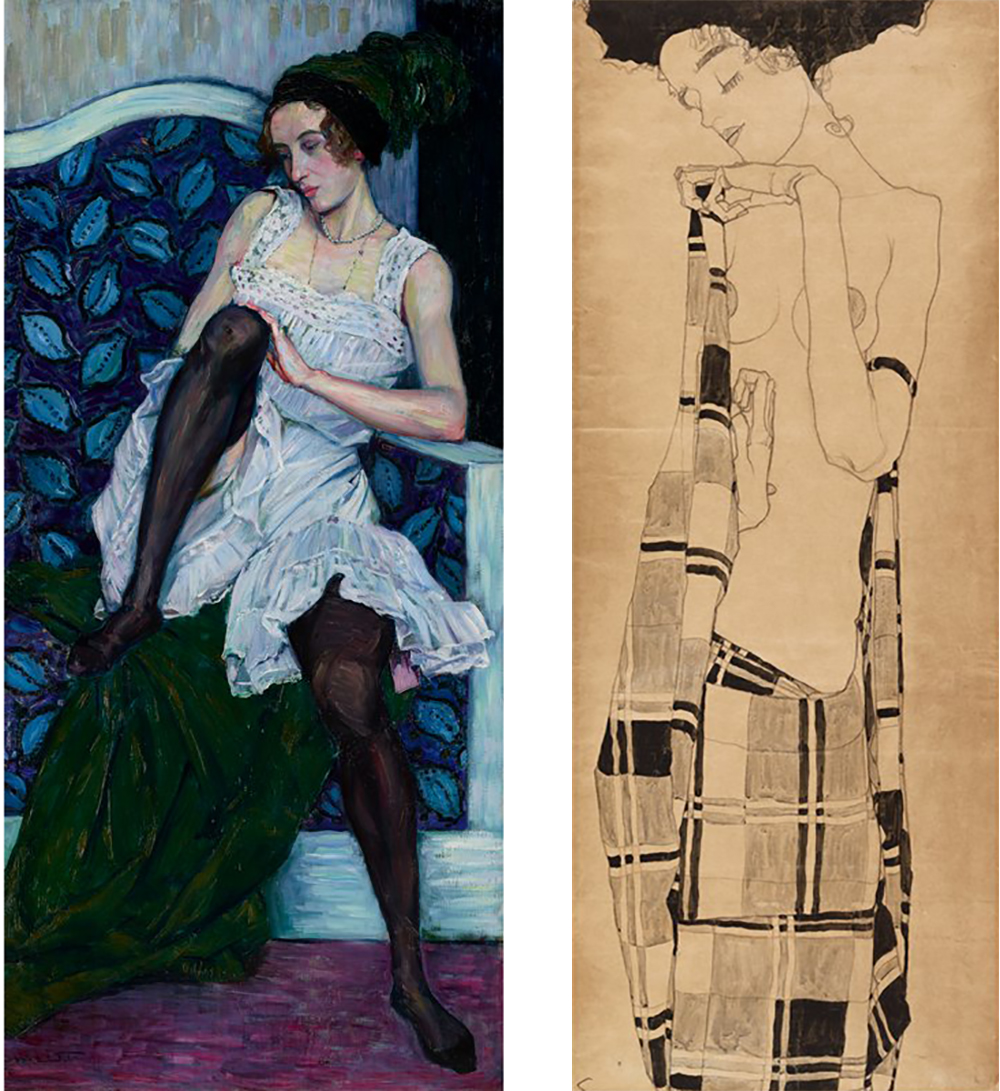

At the beginning of the twentieth century the Viennese enjoyed reading about brothels almost as much as they enjoyed visiting them. The German novelist Margarete Böhme’s 1905 best seller The Diary of a Lost Girl, the purported autobiography of a female sex worker, had been a huge sensation. Its popularity, wrote the critic Siegfried Kracauer on the occasion of the 1929 film adaptation directed by G.W. Pabst, “rested upon the slightly pornographic frankness with which it recounted the private life of some prostitutes from a morally elevated point of view.” Josephine Mutzenbacher, or The Story of a Viennese Whore, as Told by Herself, another lurid purported memoir in which a veteran courtesan graphically recounts her preadolescent sexual exploits, was published anonymously in 1906—likely written by Bambi author Felix Salten—and is still in print today.

In this literary climate, it is unsurprising that the fin de siècle Viennese writer Else Jerusalem’s 1909 novel Der heilige Skarabäus (The Sacred Scarab, retitled The Red House in a later English translation) was a cultural phenomenon. Several male reviewers praised the novel—backhandedly, it would seem—for its sociological texture and cultural detail rather than for any inherent literary qualities. But it was still a best seller. By the time the Nazis got around to burning it in 1933, Der heilige Skarabäus had gone through some forty printings. As with many best-selling novels, the overwhelming initial attention and shock eventually wore off; in 1943 Jerusalem died in Argentina, “alone and somewhat forgotten,” as her daughter later put it.

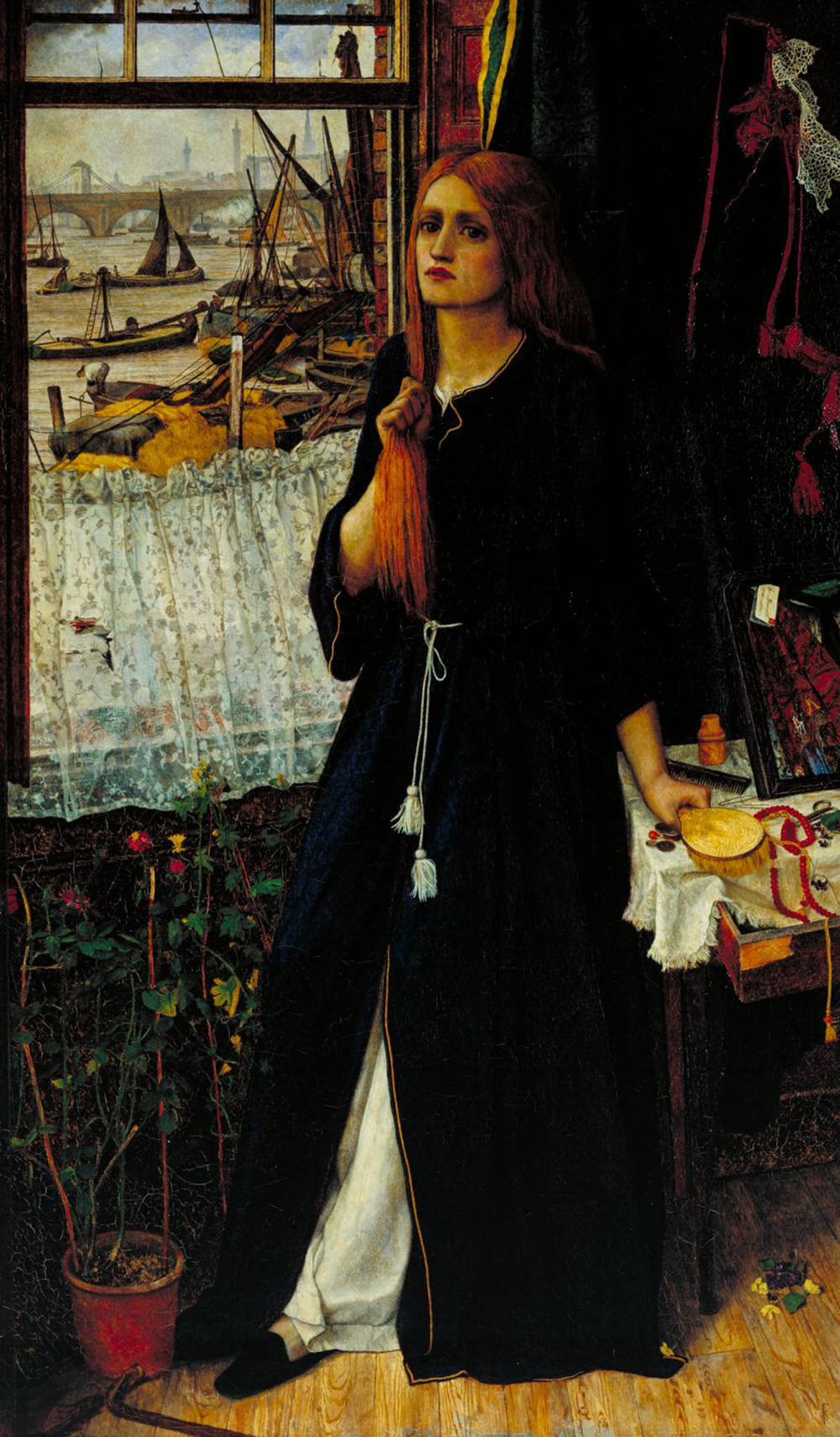

Though seldom read outside of academic circles today, Jerusalem was a pioneering feminist who wrote perceptively about the lives of Viennese sex workers and their role in the political economy of the city’s nightlife. Increasingly encouraged to register with the authorities for a variety of ostensible public health and safety reasons—though the 1,478 women registered as prostitutes in 1905 were just an estimated tenth of all the sex workers in the city, according to historian Nancy M. Wingfield’s research—their existence was seen as a necessary evil by the public and many officials, as a source of anxiety by the state, and as a target for polemics by reformers and conservatives alike. As the proprietress of one aristocratic salon in Jerusalem’s novel advises, “All life is but a great market. One buys or one sells…that is all there is to it.” To her credit, Jerusalem paid attention to who did the buying and who did the selling, and in the process forced her readers to confront some uncomfortable questions, only one of which was why.

I first learned of Jerusalem from a BBC documentary about Vienna in the year 1908 and wanted to find out if she had indeed pioneered stream of consciousness in German literature—a laurel usually bestowed upon Arthur Schnitzler’s blistering 1900 novella Lieutenant Gustl, the inner monologue of a bored, swaggering Austrian army officer in which Schnitzler savages the anti-Semitism and toxic masculinity of his times, which later influenced James Joyce—as scholar Brigitte Spreitzer claimed. It turns out that Jerusalem likely was the first woman to deploy stream of consciousness in a German-language novel with Der heilige Skarabäus. Reading the translation this winter, I was struck by how much and how little had changed despite the perception of progress. The double standard Jerusalem exposed in her novel persists: it is still more acceptable to hire a sex worker than it is to be one.

Jerusalem was a member of Jung Wien (Young Vienna), a new generation of café-loving Viennese writers (many of them Jewish, like Jerusalem) who were struggling with the modern concept of the self and its radical departure from tradition. The group’s published work reflected both the exhilaration and confusion of new scientific disciplines and social theories. At the same time, Vienna was more than a capital city. It was the heart of decadence and psychoanalysis, sex and sexology, the city of Freud and Schnitzler and the raven-haired Adele Bloch-Bauer, Klimt’s famous lady in gold, but also of eroticism both high and low. The same year Jerusalem published The Red House, Karl Kraus, perhaps Vienna’s reigning wit, wrote “The Cross of Honor,” a riff on the absurd “graduated scale of culpability for young girls who embrace a life of vice” and the selective licensing of immorality. It was a perfect example of what Kraus called the Austrian propensity to bureaucratism: “A distinction is made between women who are guilty of engaging in unlicensed prostitution, women who falsely state that they are registered with the police morals division, and women who are licensed to engage in prostitution but who are not licensed to wear a cross of honor.”

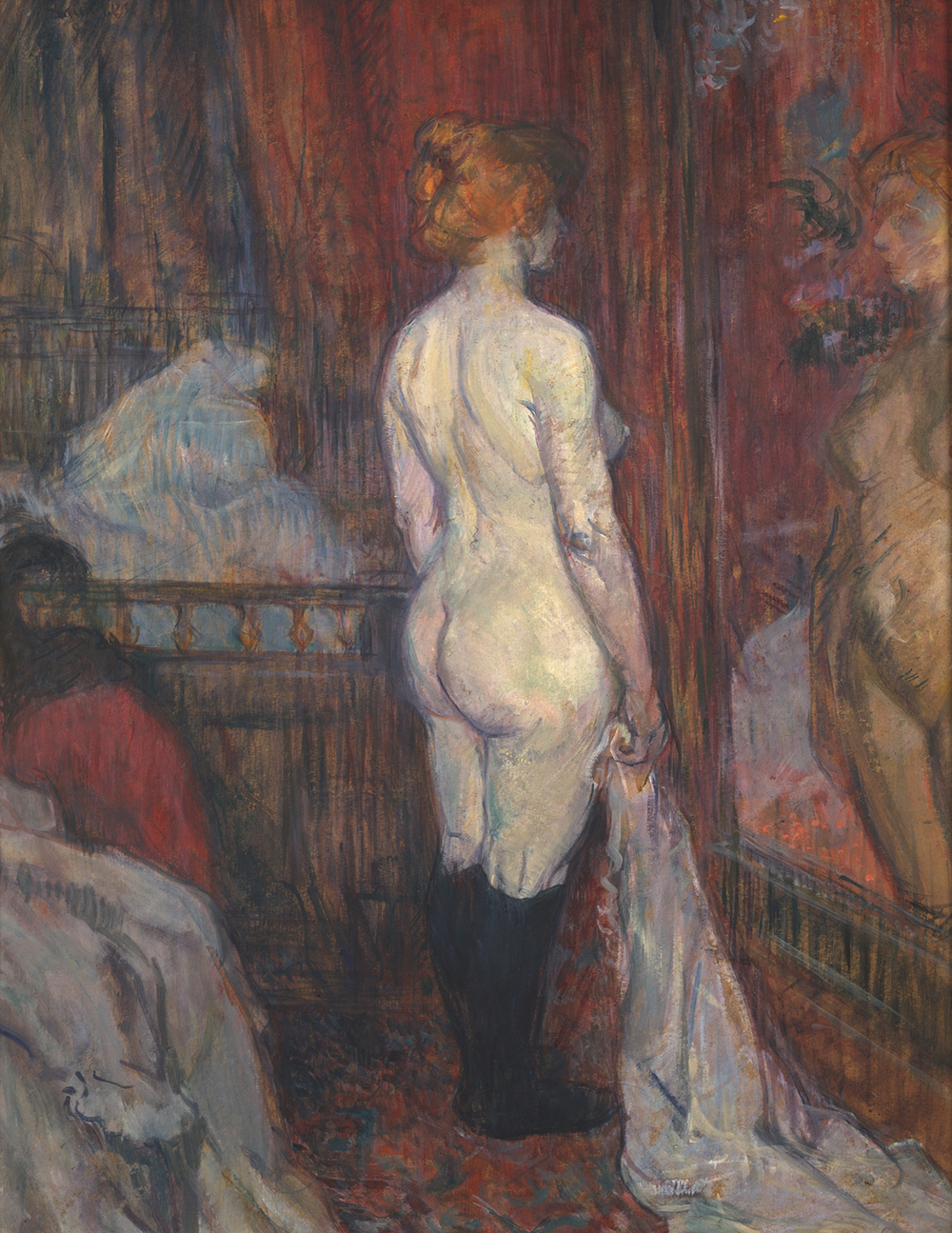

Unlike many other contemporaneous tales set in the demimonde, The Red House is a critique of bourgeois hypocrisy and exploitation; if the women of the brothel are victims, they are victims of a patriarchal society in which they are set up to lose. Jerusalem pays particularly close attention to the bodies of these women and what happens to them, alongside the rising and falling fortunes of their establishment. In the opening pages of the book, young Milada Rezek and her mother, Katerine, immigrants from Bohemia (which later became part of the Czech Republic), are residents of the finest Frauenhaus in the alley, a “well-kept building” named not for the telltale lights of the trade but after the “color of the smooth brick facade,” where the “prettiest, most successful girls” in fin de siècle Vienna reside. “To be taken into the Red House,” writes Jerusalem, “was evidence of standing and a surety of good earnings as well. A girl who was willing to work, not just drink and loaf, was well off in the Red House, and good-paying customers came willingly.” At the same time, the brothel is a business, and the madam, Mrs. Lorinser, looks after the bottom line. There is hardly an empty bed, the girls a “constant stream of young fresh material” who exist merely to enrich the madam with “money earned by their labor.”

Concealed in these detailed sociological descriptions are more far-reaching hypotheses about the roles of nature and nurture. Émile Zola famously drew on the lives of well-known Parisian singers and courtesans to create the heroine of his successful 1880 novel Nana, a deterministic class-revenge story in which the titular character uses male lust to fuel her spectacular rise out of the poverty into which she was born and, in the process, bring the French aristocracy to its knees. The Red House is a kind of Viennese Nana; the sacred scarab of the original German title is apparently borrowed from Zola’s comparison of Nana to the golden dung fly.

Katerine is a tragic character who lands at the Red House in a misguided attempt to spark the sympathy of Andreas, the rural landowner who fathered Milada and refuses to marry Katerine. She brings Andreas’ cousin Janka, her childhood friend, as a further temptation to rescue—or perhaps simply to spite him. But she loses track of her master plan in the effort it takes just to survive: “The past sank away into an unreal haze, leaving only the broken frame of a whirl of gay motes that tricked her blinded soul.” The legacy of sin and corruption, moral and physical, is a persistent anxiety for Jerusalem’s characters.

Janka wants Milada to go to a convent, “where she’ll learn honest work and prayers,” but Katerine, no stranger to unrealized futures, disagrees: “Why should she be any better than her mother?” For all its sympathy for its characters, the novel often seems to see them as fundamentally broken victims “crushed by fate.” Jerusalem dedicates the book to “dancing maidens, laughing brides, happy mothers,” asking these respectable women to take pity on Katerine, who “did not ask for charity, only for her right,” and others like her: “Let your compassion touch them gently, these victims of your happiness.” The author’s concern can appear charitable at times, the brothel a kind of social cause of which she’s particularly fond. Voyeurism with a conscience—but voyeurism nonetheless.

The plot rolls on, unwilling to grant false uplift to complicit readers. Janka briefly wins the fight over Milada’s future when the child is sent to a church-run “public school for neglected children.” But soon the brothel’s ownership changes hands, and the penny-pinching Lorinser is replaced by the rational Mrs. Goldscheider. The Red House is given a makeover, and Katerine is one of the grateful few allowed to remain at Red House 2.0—until she proves unable to adapt to the new environment, that is. She is banished to Braunau, a small town on the border with Germany, where she is forced into increasingly precarious working conditions and dies prematurely and alone, having become completely estranged from her daughter, who returns to the Red House after finding that there are no spots available for girls raised in brothels.

Milada comes of age while the new Goldscheider salon flourishes, one node in a network trafficking naive girls from provincial towns to the numerous “cabarets, wine rooms, small variety halls, public and private brothels” of the big city:

The girls were young, pretty and well trained. Really, they seemed even well-bred. There was no flavor of broken lives about them, nor the stupid impudence of the chance adventuress. In short, the Red House became a feature of city life, of itself the best assurance of success.

Goldscheider finds that “the establishment which came nearest, in appearance and management, to a respectable middle-class home was the surest guarantee of success. Places that had the flavor of cheap cabarets, dives, too closely connected with the wretchedness of the street women, might attract for a moment but could not hold the best-paying customers.” When in need of fresh “material,” she visits the cafés and the “public lying-in clinics and hospital wards” to recruit nannies, teachers, housekeepers, and unwed mothers. With the proceeds, the madam subsidizes her daughter’s education at a fancy Dresden school—and, seeing something of her daughter in Milada, she takes the orphan under her wing.

The Red House emerges as a character in its own right, its essence somehow managing to survive each subsequent iteration of the brothel. The chaos of constant turnover in one of the capital’s debauched districts underscores the precarity of sex work in the metropolis and the inexorable logic of its pitiless social system: without any rights—and often without the right documents—the clandestine (or unregulated) sex workers are entirely at the mercy of a succession of madams, hygiene officials, and police officers who can inspect and evict them for any reason at any time. In fin de siècle Vienna, sex work was inextricable from the precarious housing situation. As the new century approached, Vienna’s population swelled, doubling to nearly 1.6 million by 1900, and all these people needed somewhere to stay. Among the immigrants were many Jews, who began to relocate when Austria granted Jews full citizenship in 1867. Unsurprisingly, this sudden proximity to strangers in intimate settings inspired all sorts of anxieties about the types of encounters taking place between Jews and non-Jews, men and women, adults and children.

Jerusalem knew these facts better than most, having witnessed the infamous trial of madam Regine Riehl in 1906. Though it was Riehl—a gentile—who was accused of abuse, embezzlement, fraud, pandering, and a host of other crimes, Vienna’s anti-Semites seized on the role played by Antonie Pollack, her Jewish deputy. Jerusalem seems to have incorporated much of what she learned from the trial into her fiction, from the exploitation of immigrants to the ethnic features of Mrs. Goldscheider, “a slender woman with waved red hair and a delicately cut Jewish nose,” a “custodian of the pleasures of love” who “brought to bear on her new enterprise all the pedantic accuracy and businesslike methods she had learned in a long mercantile career.” In her sober hands, we are told, the Red House is transformed into “a shop for love in which the stereotyped prostitute pattern was refreshingly absent.”

Arthur Schnitzler called The Red House “a very strange book.” The author first met Else Jerusalem in May 1909; according to his journal, she “proved to be a pleasant and clever woman” during their discussion of “the genesis of her book, her youth, her plans—her grammatical errors, her lack of freedom, her awkwardness as an Aquarius.” She was still young when her best seller was released—only thirty-two—but, as a woman, she had had to fight to be taken seriously.

Else Kotányi was born in Vienna in 1877, the only daughter of well-to-do middle-class Hungarian Jews. She was something of a prodigy, auditing classes in literature and philosophy at the University of Vienna at the age of sixteen as one of the first außerordentlichen Hörerinnen (extraordinary students, part of a non-degree program) in the university’s history. (Restrictions on female enrollment were formally abolished only in 1897, some 532 years after the university was first established.) Perhaps because she had been taught to do more than cut noodles and had advanced further than most girls her age, she wrote passionately about education in all matters of life. In her 1902 book-length essay Gebt uns die Wahrheit! Ein Beitrag zu unsrer Erziehung zur Ehe (Give us the truth! A contribution to our marriage education) and in the 1899 novella collection Venus am Kreuz (Venus on the cross) she had rooted the oppression of women in culturally sanctioned ignorance about the world in which they lived. In Shifting Voices: Feminist Thought and Women’s Writing in Fin-de-Siècle Austria and Hungary, scholar Agatha Schwartz suggests that for Jerusalem, the way forward “lay in a reclaiming of women’s power over their daughters’ upbringing.” Toward that end, she lectured and advocated for protections against the trafficking of women and girls, especially immigrants. In 1901 she married industrialist Alfred Jerusalem. The couple had two children, one of them the Communist writer Fritz Jensen, who was killed in an unsuccessful assassination attempt on Zhou Enlai, the first premier of the People’s Republic of China.

Shortly after The Red House was published, Jerusalem met the man who would become her second husband, embryologist Victor Widakowich. The scandal of their affair—which began when both were married to others—would eclipse whatever scandal had been caused by the novel. In January 1911 Else divorced Jerusalem and converted to Lutheranism in order to marry Victor, though she kept her first husband’s name. The following month, Victor’s ex-wife, Antonie, died by suicide. The newspapers had a field day with this real-life Viennese drama. The pair emigrated to Buenos Aires, where Victor was appointed professor and, eventually, head of the city zoo. Family photos show Victor crossing the street with a costumed chimp and Else holding a tiger cub in her lap.

Returning to Argentina aboard the Cap Polonio in 1925, Jerusalem caught the eye of a fellow German-speaking passenger who gave her the nickname “Panther Cat.” It was Albert Einstein, who was passing through Buenos Aires on his South American tour. Jerusalem became part of Einstein’s inner circle in Argentina, serving as his confidante and interpreter to the press. “It was funny to see the great sage accompanying her to the fair or helping her to do the shopping,” Jerusalem’s daughter later wrote. But Jerusalem would never truly feel at home in her new country. According to the historian Ronald C. Newton’s German Buenos Aires, 1900–1933: Social Change and Cultural Crisis, like many of her fellow immigrants, Jerusalem found herself culturally bereft in Buenos Aires, which she considered irredeemably provincial and paternalistic. “How many women who return to the homeland in high spirits,” she wrote, “come back again bearing the painful discovery I don’t know what’s happening—but I don’t understand people anymore—everything has become strange.”

American readers of The Red House had to wait until 1932 for an English translation. “The book can be useful in America as it has been in Europe,” claimed the Macaulay Company, the house behind the House, now that “a change in our social attitudes” had rendered this novel of bad manners suitable for public consumption. Translated by R.I. Marchant and bound in red cloth, the American edition featured a sleek design and an Art Deco title page. Prohibition was over, and the Great Depression had left readers hungry for a variety of dramas and disappointments very different from their own. Looking over the era’s best sellers, it would seem that Jerusalem’s novel would have chimed with the trend for depressing narratives in which suffering was ultimately ennobled, like Pearl S. Buck’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Good Earth—the first of a trilogy that also featured sex workers.

It wasn’t easy to break through in a crowded market. Mainstream publishers picked their top performers ahead of each season and passed the recommendations on to booksellers and reviewers. The Red House was featured in a preview in Publishers Weekly in December 1931 alongside copies of Murder in the Night and Super-Gangster and a pile of coins below the slogan “Keep on the GOLD STANDARD.” (Excruciating financial puns seem to have been the stock in trade during the Depression.) “True realism in the best tradition of Zola and Balzac,” proclaimed an ad in the New York Times Book Review in January 1932. But the novel was not advertised among these titans of French literature; instead the publisher promoted The Red House next to salacious romance fare like What Price Virtue? and A Good Time Man. It featured perhaps most prominently in registers of prohibited books.

The novel was more successful in Europe, where it translated more readily and inspired a slew of films set in the demimonde, including 1928’s Die Rothausgasse, directed by prolific Viennese filmmaker Richard Oswald. Foreign audiences saw what officials and censorship boards wanted them to see in these screen adaptations. (In Soviet Russia, for example, the Red House served as a symbol of the unique evil of capitalist exploitation.) If Jerusalem was not the first to write about brothel life or to air Vienna’s dirty laundry, she was perhaps the first to say aloud that which was commonly kept quiet. Not unlike the investigative reporting undertaken by Emil Kläger and Hermann Drawe, whose intimate photographs of and popular slide shows on the appalling living conditions of Vienna’s poorest were collected in the 1908 book Durch die Wiener Quartiere des Elends und Verbrechens: Ein Wanderbuch aus dem Jenseits (Through the Viennese slums of poverty and crime: A travelogue from the netherworld), Jerusalem’s novel, in its own melodramatic way, brought faces from the city’s other half out of the shadows and into the full view of respectable society. In the minds of Vienna’s officials, who did their best to stop Kläger and Drawe, muckrakers like these did nothing but undermine the city’s stellar image. But it takes courage to set the record straight, and Else Jerusalem was nothing if not courageous.

The author would like to thank Dr. Adrian Daub and Dr. Nancy M. Wingfield.