“The Yellow Press,” by L.M. Glackens, from Puck, 1910. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In the spring of 1904, a letter to a New York newspaper made the case for a new kind of presidential candidate. “The American people—like all people—are interested in PERSONALITY,” the writer noted. “He appeals to the people—not to a corporation. Not even the most venal of newspapers has suggested that anyone owns [him], or that he would be influenced by anything save the will of the people in the event of the election.”

The letter was referring to William Randolph Hearst, who owned several large newspapers himself. This vast media empire was matched only by Hearst’s ego, which was on rich display during his failed quest for the Democratic presidential nomination that summer. “It is not simply that we revolt at Hearst’s huge vulgarity; at his front of bronze; at his shrieking unfitness mentally, for the office he sets out to buy,” one editorialist explained in a rival newspaper. “There never has been a case of a man of such slender intellectual equipment, absolutely without experience in office, impudently flaunting his wealth before the eyes of the people and say, ‘Make me President.’”

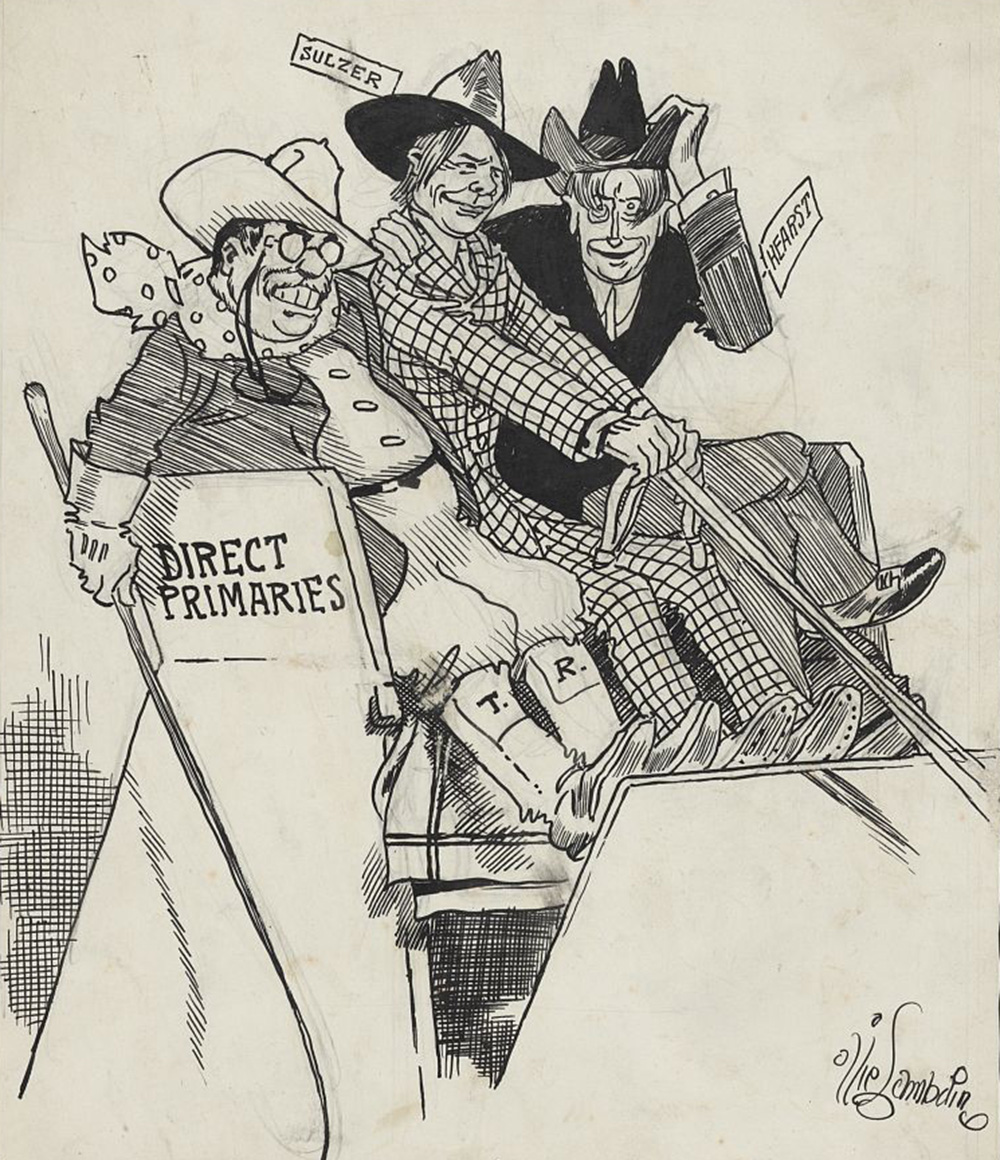

Hearst lost the Democratic contest to Alton J. Parker, who would go on to lose to GOP incumbent Theodore Roosevelt. In recent weeks, some Democrats have put forth their own favored media empire-builder, Oprah Winfrey, as a possible challenger to President Trump in 2020. But that was a bad idea in 1904, and it’s a bad idea now. Hearst’s story should remind us of the dangers of promoting media titans for the executive branch, whether you share their ideas or not.

In his early years, Hearst’s politics were so progressive that critics called him a socialist. Elected to Congress in 1902, he put forth bills to establish stronger railroad regulations, an eight-hour day for government workers, and the nationalization of the telegraph industry. But he rarely followed up on his bills or bothered to appear in Congress at all: of two hundred roll calls in his first year, he missed all but four. The day-to-day grind of politics bored him.

Hearst was interested in publicity and—most of all—in power. He burst into the newspaper industry via lurid crime reporting and staged stunts, such as hiring a swim champion to rescue marooned fishermen in the San Francisco Bay; Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner featured pictures of the rescued men drinking coffee around a stove at the newspaper’s offices the following day. He also used his papers to push his pet Progressive causes, including women’s suffrage and the popular election of senators.

But his chief goal was to sell papers, and Hearst was especially good at that. He acquired the New York Journal in 1895 and increased its circulation from 30,000 to 100,000 in a single month. Hearst would repeat the same pattern in San Francisco, Chicago, and Los Angeles, using blood, gore, and sex to gin up readership. His most famous stunt came in 1897, when Hearst sent a team of journalists to free an attractive young woman in Cuba from a Spanish prison. The Journal called her escape “the greatest journalistic coup of this age,” even as competing newspapers charged that the whole matter was a hoax. To Hearst, that didn’t matter. “A newspaper without promotion,” he said, “is like winking at a girl in the dark.”

And promotion did often mean playing fast and loose with the truth if it served Hearst’s purposes. His papers infamously tried to drum up support for an American intervention in the 1890s on behalf of the Cubans, who had been ruled for four centuries by Spain. When a reporter sent to Cuba failed to uncover popular resistance to Spanish control, Hearst told him not to worry. “You furnish the pictures,” Hearst allegedly instructed, “and I’ll furnish the war.”

So he did, playing up sensational accounts of Spanish atrocities. Despite his boast, Hearst didn’t manufacture the Spanish-American War of 1898. But he certainly helped fuel it, which widened his readership—and his coffers.

Hearst’s darkest moment came in the 1930s, when he revived the slogan “America First” in an effort to keep the United States out of any conflict with Nazism. Hearst had begun using the phrase in his newspapers during World War I to oppose both war against Germany and aid to its enemies. His pro-German stance became even stronger with the rise of Adolf Hitler, whom Hearst admired for squelching Communism. He was much more hostile to the Japanese, whom he accused of plotting with Mexico to attack the United States.

Even when documents allegedly demonstrating this conspiracy were exposed as forgeries, Hearst refused to give ground. “The essential facts contained in the documents were not fabricated,” Hearst insisted, even if the documents themselves were.

After his failed 1904 White House bid, Hearst ran unsuccessfully for New York mayor in 1905, New York senator in 1906, and then president again—this time as an independent—in 1908. His presidential campaign went nowhere, in part because Hearst refused to take any advice. “We have no prominent men associated with us,” he bragged. “If I have prominent men connected with me, I will have to consult with them—and I don’t consult with anybody.” Hearst had already become a pariah among Democratic party bosses, who viewed him as a loose cannon and a megalomaniac. “He is controlled by the idea that he is greater than the Democratic Party,” one disgruntled leader said. “He is [a] slave to passion and egotism. His creed is that everybody who is for him is an angel, while everybody who is against him is a demon.”

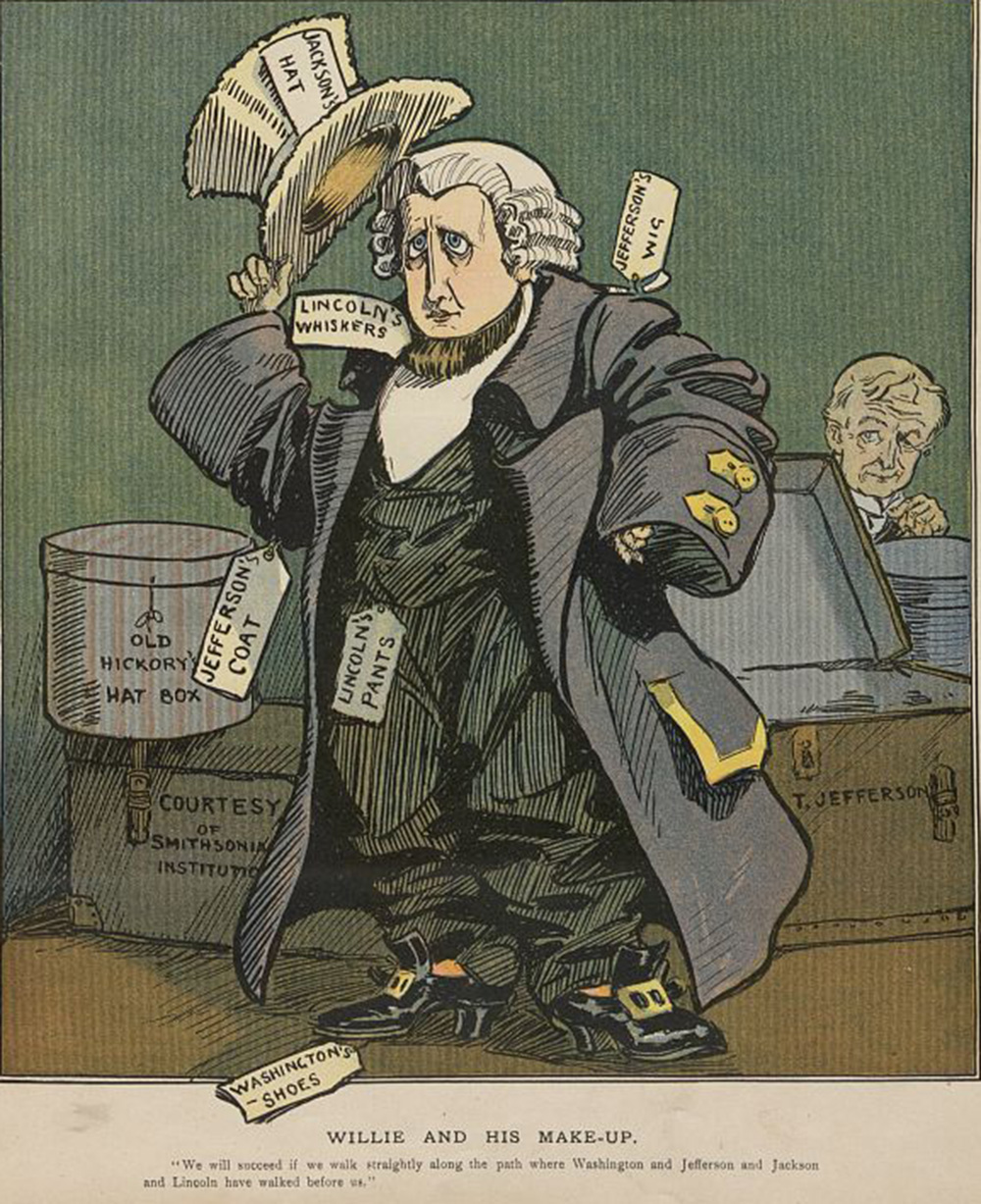

Most of all, critics blasted the shameless manner in which Hearst used his own media empire to support his political campaigns. Hearst newspapers ran block headlines in praise of him throughout the 1904 presidential contest and during his subsequent runs for office. Sometimes they took a man-on-the-street approach, like “BANK PRESIDENT TELLS WHY HE IS FOR HEARST”; other articles reported fervent expressions of public sentiment, such as “A HEARST VICTORY! CRY POLICEMEN’S WIVES.” Hearst and his wife appeared as Mr. and Mrs. Santa Claus at a much-chronicled 1903 Christmas Eve party in New York, presenting toys and candy to thousands of children. Young athletes received “Hearst cups” in the city basketball tourney he sponsored, and “Hearst coffee wagons” distributed sandwiches and hot drinks to the poor.

But Hearst mostly disdained campaigning in person, believing that that his self-manufactured media image would carry the day. He was wrong. Although he controlled eight daily newspapers, he couldn’t control how other papers—and other politicians—depicted him. In 1906, during Hearst’s failed quest for the New York governorship, Theodore Roosevelt dispatched an aide to suggest that the assassin of Roosevelt’s predecessor, William McKinley, had been inspired by the Hearst press. It was then falsely reported that the murderer had been carrying a Hearst paper—with an anti-McKinley editorial—when he killed the president.

What the mass media gave, in short, it could also take away. The newspapers outside Hearst’s orbit were only too happy to do Roosevelt’s bidding, trumpeting each of his anti-Hearst statements in vivid detail. “He has enormous popularity among ignorant and unthinking people,” Roosevelt proclaimed, denouncing Hearst. “He preaches the gospel of envy, hate and unrest…He is the most potent single influence for evil we have in our life.”

William Randolph Hearst foreshadowed Donald J. Trump in many ways, although the president might even be less self-aware than Hearst was. Hearst despised Orson Welles’ now-classic film Citizen Kane, which Hearst correctly recognized as an indictment of his character and career. But Trump has called it his favorite movie, because he sympathizes with Kane’s plight: they both had a series of difficult wives and mistresses, plus a greedy public that insists on knowing more about them. “He and his wife getting further and further apart as he got wealthier and wealthier—perhaps I can understand that,” Trump told Errol Morris in 2002. But Trump—unlike Hearst—also won the presidency. And surely that helps explain the buzz around Oprah Winfrey, whose backers see her as the anti-Trump. Where he is egotistical, she is empathetic; where he is ignorant, she is informed; and where he is miserly, she is munificent.

Winfrey’s charitable efforts vastly outpace the notoriously stingy Trump. But Hearst was equally generous, often paying the medical and tuition bills of his strapped employees. And he was a great advocate of women’s causes, just like Oprah, hiring Susan B. Anthony to write articles in defense of female suffrage.

Hearst was also a believer in his own press; he owned the press. We could expect the same from Winfrey or from any other media behemoth elected to lead us. They spend their careers cultivating images, which are fickle and fleeting. When all of the other snapshots blow away, only one thing remains: the towering likeness of the giant who produced them.