Study of Sheep, by J.B.B. Wellington, 1890. British Library.

Sheep have trampled their way into our sayings and superstitions, appearing in place names and poems. When we use these words, however, we rarely think about where they come from. Shoddy, for example, now used as an adjective to describe something that is badly made, once referred to a yarn made from recycled wool; woolen rags were shredded into fibers and then mixed with a small amount of new wool to make a cheap material also known as rag wool.

A children’s favorite is, of course, “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep”:

Baa, baa, black sheep,

Have you any wool?

Yes, sir, yes, sir,

Three bags full;

One for the master,

And one for the dame,

And one for the little boy

Who lives down the lane.

The words of this rhyme have scarcely altered over the years, apart from the last line, and it’s this that may give a clue to its original message. In an early version, which appeared in the collection Mother Goose’s Melody in the mid-eighteenth century, the last line reads, “But none for the little boy who cries in the lane.” One interpretation has been that the rhyme is actually much older than we imagine, perhaps even dating as far back as the late thirteenth century.

In the late thirteenth century, King Edward I imposed a swingeing tax on wool. He needed to raise money to fight the French, and the British wool trade, which was a vastly successful industry at the time, was an easy target. Initially, the government’s plan was to simply take all the country’s stocks of wool and confiscate them for “safe custody,” so they couldn’t be exported to France. Actually, what the government planned to do was to export the wool themselves and keep the profit.

Wool merchants were furious and rose up to complain bitterly. In response, Edward I scrapped the confiscation plan and decided instead to stick extra duty on each bag of wool destined for sale; the tax became known as the maltolt, or “bad tax.” The king justified the tax on the grounds that he was risking his life in war and “his grateful subjects should happily pay their taxes.” Wool merchants saw things very differently and, angry at having to pay such high taxes on their wool, passed the costs onto the wool farmers, forcing them to accept low prices for their fleeces.

“Baa, Baa, Black Sheep” may be a reference to this difficult period, when taxes on wool were so high that only the “master” (the king) and the “dame” (the merchants) made any money from the industry, while the weeping little boy represents the shepherds and wool farmers who went home empty-handed.

The reference to the “black sheep” in the rhyme is trickier to interpret. Black sheep have been both loved and loathed in equal measure over the centuries. In terms of wool production, black sheep among a white flock were problematic. Black wool is difficult to dye, and so a black sheep in a white flock destined for cloth would have represented a financial loss. The coat color of wild sheep is usually a dark body with a pale tummy, but over the centuries shepherds strongly selected for a uniform white coat, which was easy to dye. The gene for dark fleece didn’t disappear, however; it is simply recessive—in other words, a white sheep can carry the black fleece gene within a flock, but you wouldn’t be able to tell which animal it was until it produces a black lamb.

The arrival of a black sheep from a white flock must have left ancient shepherds scratching their heads, bewildered by nature’s alchemy. And so perhaps it’s no surprise that black sheep became the target for superstitions and peculiar folk remedies. An early reference to the healing “magic” power of black sheep appears in an Old French collection of women’s folk beliefs that was translated into English around 1507 as the Gospelles of Dystaues (or Distaff Gospels). A cure for smallpox involved wrapping yourself in a black sheepskin: “Yf a woman haue the small pockes, it behoueth that her husbande bye her a blacke lamb of the same yere, and after bynde her in the skynne, and the let hym make hys pylgrymage and offrygne to saynt Arragonde, and for a trouthe she shall hele.”

Nearly four hundred years later people were still using a similar “cure” in the Outer Hebrides: “When a man was afflicted with pains in his joints, a black sheep, still living, was placed over the rheumatic limbs of the patient.” Records of folklore show a rather schizophrenic approach to black sheep: at the end of the nineteenth century it’s recorded that “one black sheep is regarded by the Sussex shepherds as an omen or good luck to his flock,” while across the water in Ireland, “if the first lamb born of the season is born black, it foretells mourning garments for the family within the year.” In Kent “a black lamb foretells good to the flock,” whereas in Orkney “it is unlucky to see a black lamb as the first of the season.”

The idea that black sheep stand out from the rest of the flock, for good or ill, probably explains the phrase black sheep of the family, someone who’s a disappointment or wayward character within in a group. It’s a near universal idea—la pecora nera in Italian, das schwarze Schaf der Familie in German, France’s brebis galeuse and mouton noir, svartur sauður in Icelandic, and so on, with some interesting regional twists; the Croatians say, “Da vidimo čija majka crnu vunu prede,” meaning “We see whose mother is spinning black wool.” Ironically, the country that has the greatest number of sheep—mainland China—doesn’t use the phrase; the Mandarin equivalent is hài qún zhī mǎ, “the horse that brings trouble to the herd.”

Sheep are, however, pivotal to Chinese mythology and celebrations. The Chinese zodiac consists of twelve animals, each one with its own distinct character. Dating back to the fifth century bc, this ancient classification system subscribes to the idea that a person’s destiny can be determined by the astrological “climate” at the time of their birth, including the position of the planets, moon, and sun.

Each year is a creature, and the animals follow each other in a predictable twelve-year cycle: rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig. Each animal has a unique set of traits that people born in those years are said to possess. Over the past hundred years or so, the “Year of the Sheep” fell on the years 1907, 1919, 1931, 1943, 1955, 1967, 1979, 1991, 2003, and 2015, and it’s a sign said to be dominated by an easygoing but perhaps frustrating docility. Those born under the sign of the sheep are, in Chinese culture, thought to be peace-loving, gentle, and patient but also timid, shy about leadership, and prone to complain.

The Year of the Sheep is also known, confusingly, as the Year of the Goat and the Year of the Ram. The Chinese word yang refers to the subfamily Caprinae, which includes sheep, goats, ibex, and all manner of cloven-hoofed creatures. In Vietnam the equivalent, mùi, is unequivocally a goat, while in Japan hutsuji is a sheep. Whatever the interpretation, however, the character traits remain distinctly passive and self-effacing. How different, then, from the Western equivalent, Aries. For followers of astrology, those born under the sign of the ram are said to be headstrong, impulsive, and restless, natural-born leaders with a will of iron but little sensitivity.

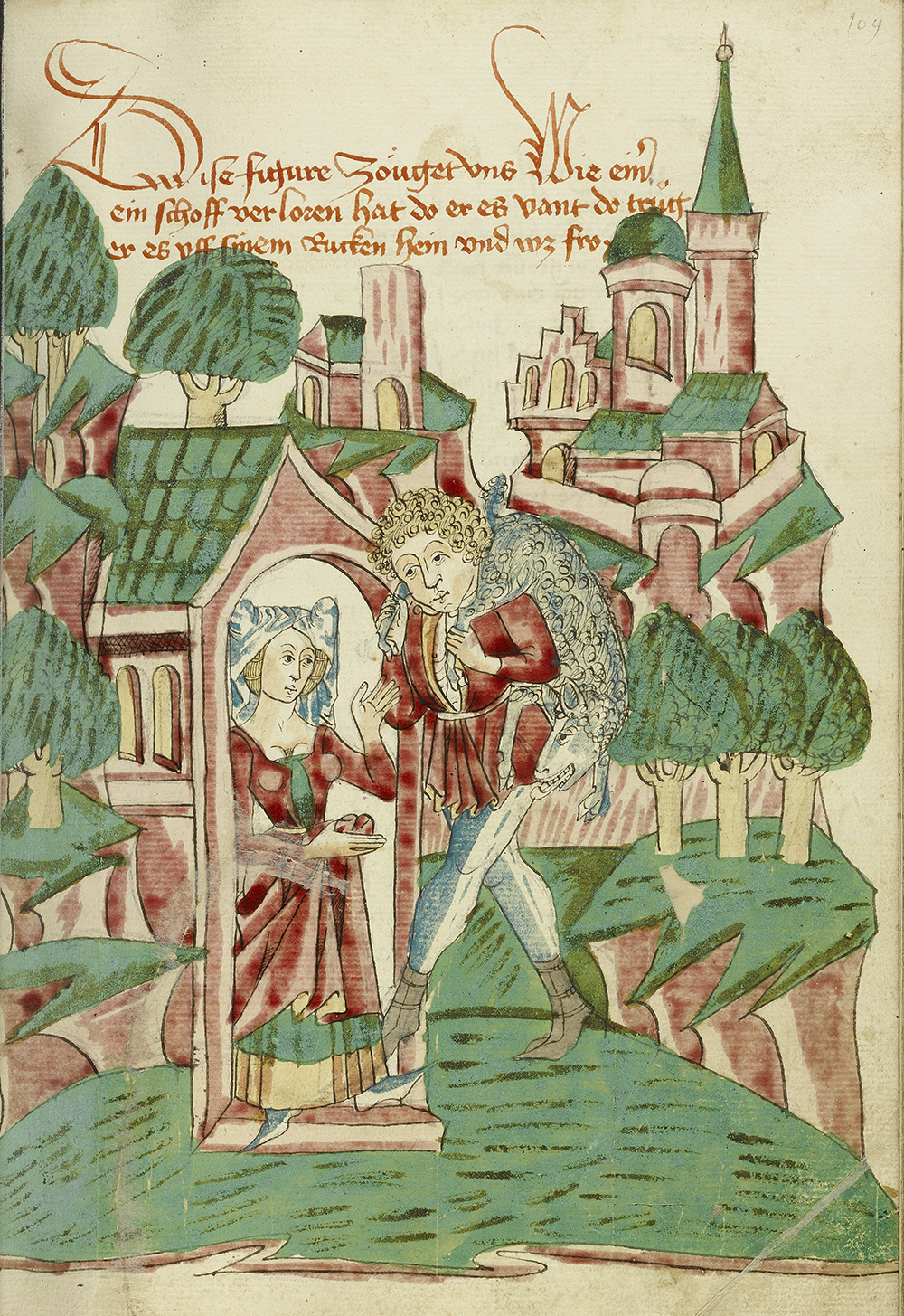

Another famous phrase, a wolf in sheep’s clothing—a person who hides vicious intent under a veneer of kindness—has a particularly ancient pedigree. It appears in the New Testament (Matthew 7:15) as part of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount: the King James Bible declares, “Beware of false prophets, which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves.” All is not lost, however, as they will reveal themselves by their actions—“by their fruits shall ye know them.” This phrase is often wrongly described as coming from Aesop’s Fables, an older text written in ancient Greece around the end of the sixth century bc, but Aesop’s large collection of allegorical stories does include plenty about sheep and wolves and the uncomfortable relationship between them.

“The Dog, the Wolf, and the Sheep” is a cautionary tale about bearing false witness—the sheep is falsely accused of stealing by the dog, with the wolf backing up his story. The sheep is found guilty of the crime, but in the end it’s the wolf that dies—the moral being that liars get their comeuppance. The tale of “The Wolf and the Shepherds” is a brilliantly pithy warning about hypocrisy. As retold by Plutarch, “A wolf seeing some shepherds in a shelter eating a sheep came near to them and said, ‘What an uproar you would make if I were doing that!’ ” “The Wolf and the Lamb” is a rather more depressing tale of tyranny: a wolf, wanting to eat a lamb, justifies it by listing all the things the lamb has done wrong in his short life. The lamb protests his innocence, but the wolf eats him anyway, finding other excuses to commit the act. The moral, one suspects, is that a bad person will always find a reason for his actions.

From Follow the Flock: How Sheep Shaped Human Civilization by Sally Coulthard, published by Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2021 by Sally Coulthard. All rights reserved.