A serpent, after Conrad Gessner, 1613. Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0).

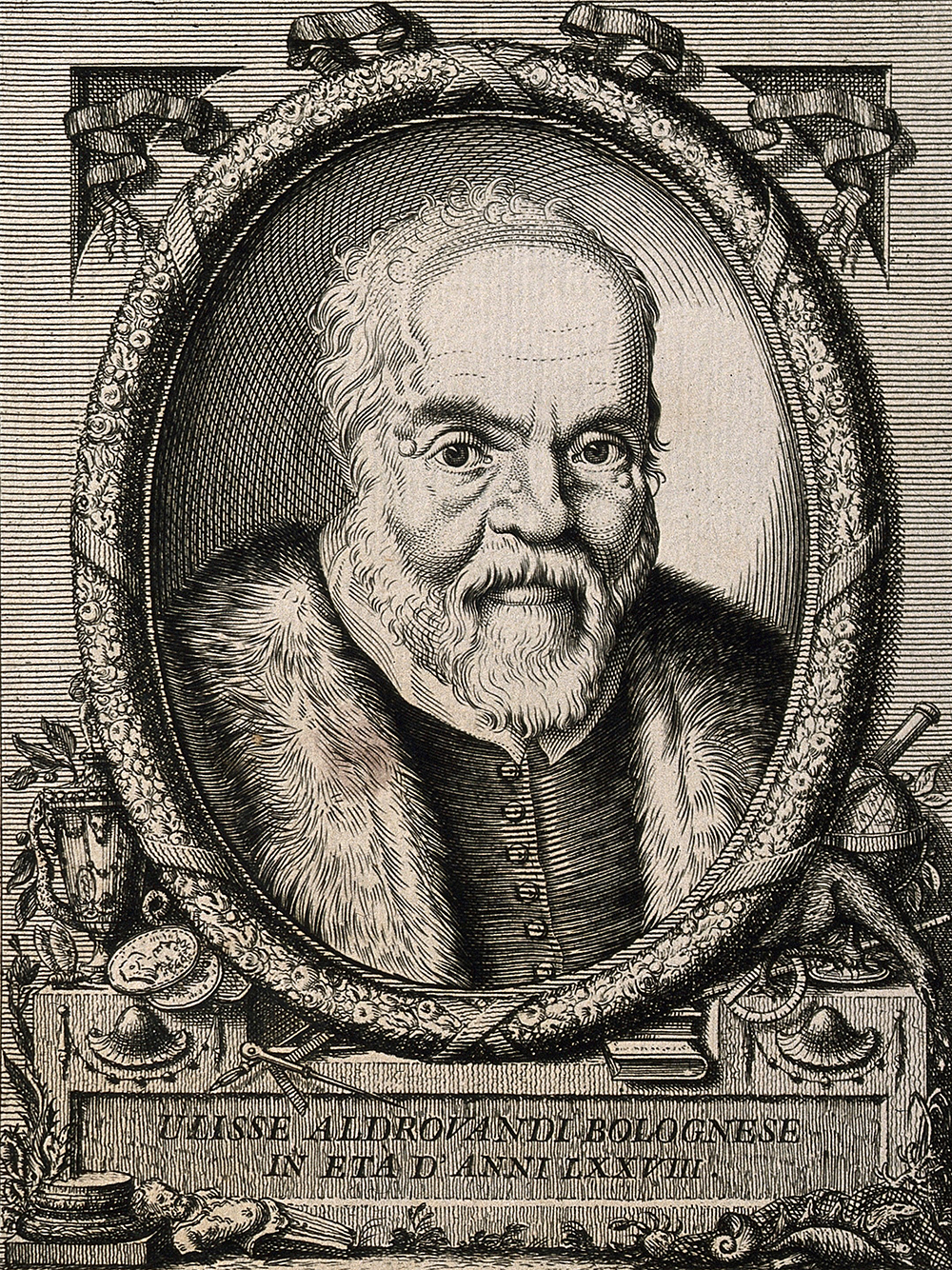

In a letter dated October 15, 1558, Ippolito Salviani, the personal physician to Pope Paul IV, remarked to the young naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi that Conrad Gessner’s book On Fish would soon be available in Italy, “even though it cannot be read without a license from the inquisitors since all of his works are reprobate.” Aldrovandi and Salviani had exchanged letters for several years on the topic of fish, about which the two physicians were preparing books. They sent each other information and specimens from their respective fish markets in Bologna and Rome, and they kept abreast of recent publications by other naturalists across Europe interested in aquatic species. Salviani’s 1558 letter indicates that even in the months before the papacy of Paul IV issued the first Roman Index of Prohibited Books, learned physicians had begun to discuss and prepare for the banning of works written by important Protestant colleagues. Gessner, a follower of the reformer Huldrych Zwingli, believed the virtues of his actions during his life did not influence his salvation; likewise, the excellence of publications did not prevent his forthcoming damnation in the Pauline Index of 1559. Nevertheless, from his position of influence in Rome, the papal physician Salviani was certain that he would be granted a license to continue reading the Swiss Protestant’s works, remarking to Aldrovandi, “I know that they will give me a license.”

The Pauline Index was an aggressive effort by Catholic authorities in Rome to assert papal authority over the circulation of knowledge in Europe. It prohibited the works of nearly six hundred authors, including many of the most prominent physicians of Northern Europe. Yet the Index neither fully prevented medical scholars from reading the prohibited works of their heretical colleagues nor kept them from discussing these works, sometimes even with the prohibited authors themselves. The 1559 Pauline Index of Prohibited Books placed explicit and punishable boundaries on intellectual relationships within the European medical community, in addition to the practical obstacles that existed due to strong personalities, distance, and war. Despite these challenges, the medical republic of letters in which Aldrovandi, Salviani, and Gessner took part would continue to facilitate the exchange of books, ideas, and letters in the face of Catholic prohibitions.

Over the course of the sixteenth century, subsequent Indexes of Prohibited Books continued to prohibit the works of important physicians from circulating in Italy, and Italian physicians continued to protest and find creative ways to evade the prohibitions, often by way of contacts maintained through the exchange of letters.

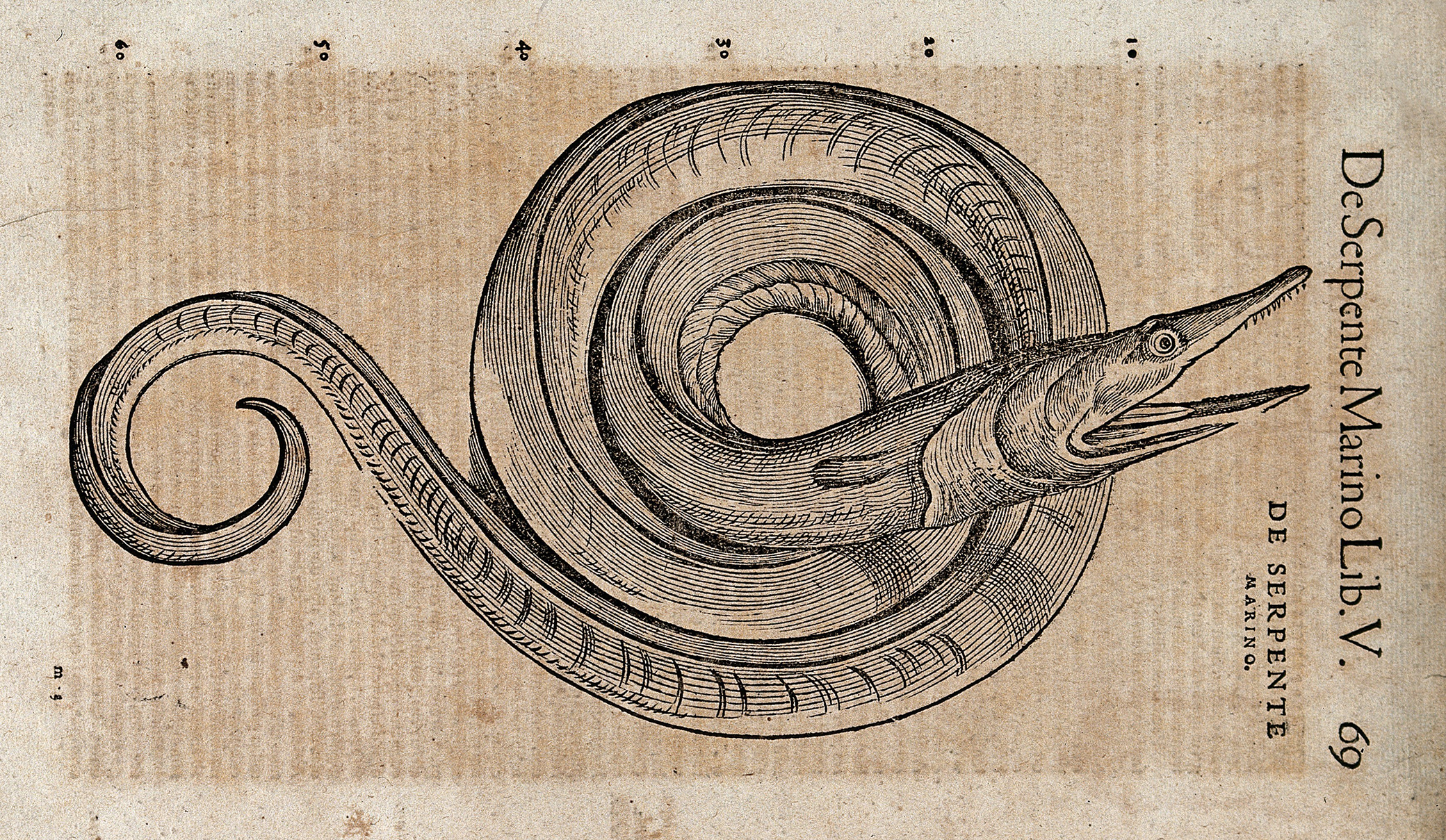

In January 1559, the Pauline Index was distributed across Italy condemning all works written, edited, printed, or commented on by heretics, works published recently and anonymously, and the vernacular Bible. It also required booksellers to present lists of their merchandise to the local inquisitor and priests to deny absolution to people who owned prohibited books.

The Pauline Index divided authors into three classes. The first class included a list of authors whose written works were banned in their entirety. Authors listed in the second class had only certain of their books banned, while others were permitted. The third class consisted of anonymous books or books of uncertain authorship. The Pauline Index placed all writings by heretics in the first class, which included all Protestant authors even if the content of their works was not religious, thereby tying the authors’ religious identities inextricably to all of their writings. The second class of prohibitions included books that were threatening to the Catholic faith but written by authors who were not heretics. As soon as the Index was published, physicians including Aldrovandi and Salviani petitioned to keep certain prohibited medical texts, and Catholic authorities in Rome started to devise alternatives to the complete prohibitions placed on these books. In February 1559, less than two months after the Pauline Index was published, the Vatican released the Instructions Regarding the Index. From the outset, the prohibition of medical books represented an exceptional case that demanded a more nuanced approach to these texts than book burnings.

The Pauline Index placed prohibitions on forty-seven authors who were trained or practicing as physicians. All except four medieval authors—Arnald of Villanova, Pietro d’Abano (also known as Petrus Aponensis), Marsiglio di Padova (Marsilius of Padua), and Raimundo Sabande (Raymond of Sabunde)—were contemporary authors who lived into the sixteenth century. The reasons for their inclusion in the Index varied, but nearly all were banned for their participation in heterodox religious groups rather than the medical content of their writings. Many of these men were Europe’s leading physicians and members of the medical republic of letters.

Italian physicians responded immediately to the limits imposed on their medical republic of letters by the Pauline Index. This community was the most bookish part of late Renaissance medical practice, and physicians resented the limitations that the Index imposed on the books and libraries so necessary for their profession. Andrea Pasquale, the physician to the Duke of Tuscany, wrote of the Pauline Index in 1559, “From this is now born a huge inconvenience, that all doctors who for thirty or forty years have studied and thirsted for their books with their vigils and studies, are now deprived of them.” He further complained, “If there had been physicians or philosophers present, it would not have happened like this,” but because the Index was carried out by monks, matters of medicine were of little importance. Physicians felt that their scholarly work was being undermined by ecclesiastical authorities. The medical community needed its books; it relied on relationships established through travel and letters and thrived on learned debate, new editions of texts, and large reference volumes, all published in print. In the years immediately following the Pauline prohibitions, the medical community responded by finding new ways to maintain the scholarly relationships in person and in print that had been so vital to developments in medical knowledge in the early sixteenth century.

Rather than presenting their books to be burned as the Index required, professors in Bologna instead presented lists of books for which they hoped to receive exemptions from the prohibitions. Throughout February and early March, the leaders of the city and university of Bologna repeatedly voiced the concerns of the learned men of the city to Ambassador Giovanni Aldrovandi in Rome. Professors of medicine, law, and the arts proposed long lists of “most useful and necessary authors in medicine” that did not deal with matters of religion and requested that the volumes be excused from the far-reaching Pauline prohibitions.

Aldrovandi, a prudent ambassador, confessed wistfully in a letter dated February 4, 1559, “To be completely honest in my description of their lists [of books] that do not cause harm, it is that wanting too much, they will not achieve anything.” Paolo Costabile, the Master of the Sacred Palace—the pope’s theologian—confirmed that it would not be possible, based on the list provided, to obtain a general license for the whole university. Instead, doctors would have to apply individually for the books that were “most necessary for their profession.”

With the advent of the Pauline Index, university professors joined a dissenting chorus of professionals whose livelihoods were at risk due to ecclesiastical censorship. In early 1559 the guild of bookmen in Venice banded together to pressure the papacy to moderate the Pauline Index and insisted that its members toe the party line. The Venetian government supported the bookmen in 1559, declaring that if the Inquisition wanted to burn books, it would first need to buy them. In Florence, Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici reacted similarly, suggesting that the burning of books be a “fire for show” so as not to threaten the “poor booksellers.” In Rome, Cardinal Ghislieri was unsympathetic to these state efforts to protect booksellers. He protested that in times of plague, people willingly burned the goods in infected houses to protect the city despite financial losses. Ecclesiastical language comparing heresy and plague highlighted the risk that the Church contended forbidden books could pose for spiritual health, but for printers, publishers, booksellers, and scholars, printed books offered intellectual and fiscal opportunities that outweighed the risk.

The Bolognese physician Ulisse Aldrovandi followed his correspondent Salviani’s example by applying for licenses to keep and read the prohibited books in his library. In January or February 1559 Aldrovandi applied, with unknown result, for a license from his Jesuit confessor Francesco Palmio. The request was forwarded to the General of the Order, Jaime Laynez, and listed as a warrantor Aldrovandi’s brother Teseo, who was in Rome as the procurator of his order, the Canons Regular of San Salvatore. We know for certain that Aldrovandi was granted one reading license in 1566 and another in 1595–96, and that the inquisitor of Bologna wrote a special license into his copy of Theodor Zwinger’s Theatrum vitae humanae granting Aldrovandi permission to read it in Villa Saint Antonio on August 4, 1603. Physicians took pains to protect their libraries in the wake of Catholic prohibitions.

In 1565 Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti of Bologna famously remarked that in his city, “the Index of Prohibited Books has done little.” In the case of Aldrovandi, archival evidence suggests otherwise. In a letter dated April 1, 1559, approximately two months after the Index was published in Bologna, Aldrovandi’s friend Alfonso Cattanio, professor of medicine and natural philosophy at the University of Ferrara, consoled Aldrovandi on the recent incineration of part of his library. Cattanio expressed his “great sadness” upon hearing of “the burning of your books.” He continued, “I would offer you some comfort if I did not know you to rise again in the things of this world, as the palm does even when it is oppressed, after you heard of the loss of many of your labors, studies, and vigils, and through this the damage of the many very rare works that you sought with so much yearning in order to furnish your study.”

While the letter does not explicitly state that these book burnings were a direct result of the Pauline Index, it seems likely that Aldrovandi’s past encounters with the Roman Inquisition and new status as professor in the university could have forced him to comply with rules that other scholars largely ignored. It also seems likely that not all of Aldrovandi’s books written by heretical authors and banned on the Pauline Index were actually burned. The last page of his expurgated copy of Gessner’s On Rare and Wonderful Herbs is signed in Aldrovandi’s own chicken-scratch hand “Totum perlegi” (“I read it all”) and dated July 23, 1556. It seems likely that most of Aldrovandi’s medical books were spared but that he was forced to destroy religious works written by authors on the Index. While Paleotti was right that the Index of Prohibited Books had not accomplished its full goal of ridding Bologna of prohibited works, it brought certain individuals, and especially their libraries, under close scrutiny.

Reprinted with permission from Forbidden Knowledge: Medicine, Science, and Censorship in Early Modern Italy by Hannah Marcus, published by the University of Chicago Press. Copyright © 2020. All rights reserved.