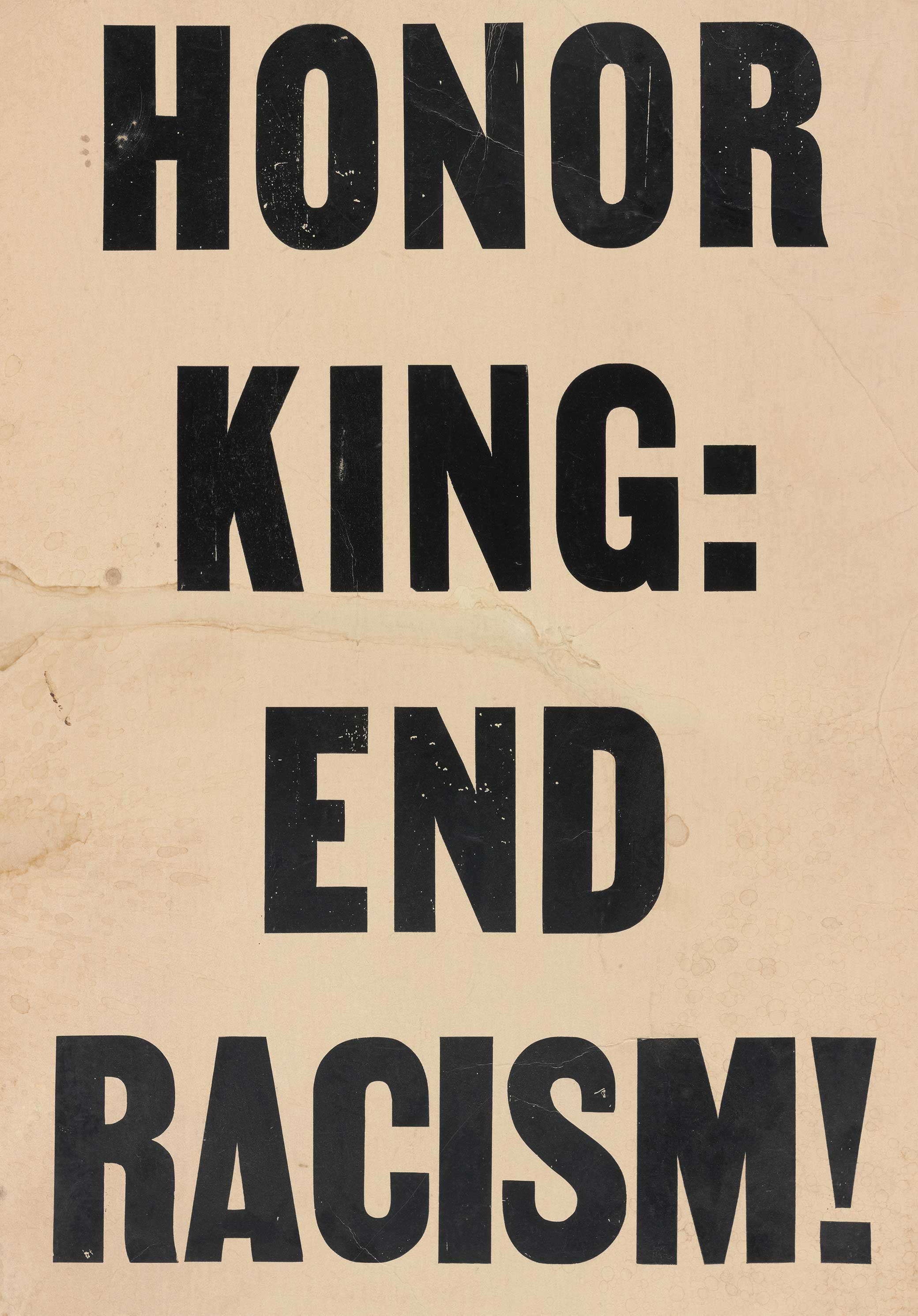

Poster from 1968 march in Memphis. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division.

In 1979 the United States had nine annual federal holidays. To create long weekends for workers and reduce disruption to industrial production caused by midweek holidays, Congress rationalized the nation’s calendar in 1968 to create Monday holidays. The Monday Holiday Act of 1968 combined Lincoln’s and Washington’s birthdays to create Presidents’ Day on the third Monday in February. Further, Memorial Day, Labor Day, Columbus Day, and Veterans Day became Monday holidays. Holidays that were powerfully identified with a specific date such as Independence Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas Day remained unchanged. After the reform, only two holidays honored specific individuals: Columbus Day and Christmas Day.

Federal holidays are exactly that—they apply only to federal government employees; neither state nor local government employees receive federal holidays, nor do employees in the private sector. Martin Luther King Jr. holiday advocates knew, however, that private and public sector employers often aligned their calendars with the federal government’s. Accordingly, they hoped a federal King holiday would encourage states, local governments, and private sector employers to follow their lead. In 1979 the Judiciary Committee claimed that eleven states had a King holiday, but holidays dedicated to King were outnumbered by Southern holidays dedicated to the birthdays of Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Jefferson Davis, plus Confederate Heroes Day and Confederate Memorial Day. There were no holidays dedicated to women at all.

Other issues competed for political attention—among them, the campaign for full employment. In 1974 Coretta Scott King founded the National Committee for Full Employment to secure passage of what became the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act of 1978. The two campaigns sometimes fed into each other, and Coretta developed her lobbying skills fighting for full employment. She noticed that when she spoke about the holiday, it generated more public excitement than the Humphrey-Hawkins Act. Further, while Coretta and allies won passage of that act, victory was bittersweet. Congress eviscerated the act so it would never achieve full employment.

Having learned a valuable lesson—Congress was in no mood to pass sweeping liberal economic reform—Coretta turned her full attention to lobbying for the holiday. With her support, momentum quickened.

Public support for the holiday had been strong since the early 1970s, yet the near all-white, near all-male Congress needed persuading. In 1979 Michigan Democrat John Conyers, who sponsored the original King holiday legislation, reintroduced it in the House and Indiana Democrat Birch Bayh introduced a Senate version. Enough pressure had built to force Congress to hold joint hearings of the Senate Judiciary Committee and the House Post Office and Civil Service Committee to consider the bill.

These hearings, on March 27 and June 21, 1979, provided the stage to debate King’s historic reputation, and holiday proponents sought to shape a new consensus about him. To do this, they attempted to portray King as a leader who forced the nation to live up to its highest ideals. Bayh acknowledged that a holiday would not be a “panacea for the nation’s ills,” but that the time had come to appreciate that a “black citizen has made a significant enough contribution to society to be recognized as a national holiday figure.” One way of “recognizing full citizenship” of the African American community was a holiday, and Bayh further noted the need for minority youth to have role models so they can live “within the system.” This hope, that the holiday would encourage minority youth to live within the system, exhibited a desire to fortify, not change, the political system. On the Senate Judiciary Committee, a majority favored the holiday because King’s “unique accomplishments” made him worthy of the honor. His legacy was such “that persons of all colors can strive to attain the universal goals of freedom and equality,” and setting aside a day to honor him would publicize the cause of racial justice. This position reaffirmed the politicians’ faith in American democracy and belief that since legal obstacles to racial integration had been removed, African Americans could attain freedom and equality—if they strived.

The committee’s majority agreed that King’s nonviolent method “strengthened the American ideal of government responsive to its people” and proved the nation’s ability to correct inequities within a democratic framework. This rationale paralleled civil rights memorialization that displays the nation at its mythical best, having corrected an injustice in response to minority concerns. Similarly, the House Committee on Post Office and Civil Service believed a holiday would be an “appropriate testimonial to an extraordinary individual” that would “underscore the nation’s continuing commitment to alleviate the invidious effects of discrimination and poverty.” Here the committee at least acknowledged King’s commitment to remediating poverty even if it overestimated the nation’s commitment.

Unanimous support remained elusive on the Judiciary Committee. Four Republican senators—arch-segregationist Strom Thurmond (South Carolina), Paul Laxalt (Nevada), Orrin Hatch (Utah), and Alan Simpson (Wyoming)—dissented from the majority. Thurmond had an infamous history of opposing racial integration. He ran as the pro-segregation States’ Rights Democratic Party’s presidential candidate in 1948 and continued to frustrate civil rights initiatives throughout his career.

Following his lead, Senate opposition to the bill centered on five points: economic cost, holiday traditions, King’s historic importance, state holiday alternatives, and a federal day of observance. First, Thurmond and his fellow dissenters argued that the economic cost to the government, $195 million paid to federal employees for a day off, was too expensive in an inflationary economy.

Second, the existing holiday traditions argument asserted that only Christ, Columbus, and, according to the minority, Washington—despite the 1968 reforms—had federal holidays named in their honor. Granting King a memorial equal to the son of God, the man who “discovered” the Americas, and the man who “founded” the nation seemed blasphemous to the authors of the minority report. To these dissenters, the remaining six holidays recognized events “of such magnitude that they transcend regionalism and special groups or cultures.” Implicitly, by denying King’s broad appeal they sought to define him as relevant only to the African American community, which was thought of as a special group or culture. The dissenters argued that King did not transcend the cause of “civil rights for black Americans,” therefore he was irrelevant to most Americans.

The third dissenting argument concerned King’s place in history. The dissenters alleged that King was unworthy of unique adulation by reviving charges that he had Communist sympathies and was therefore traitorous. Drawing on discredited FBI allegations, several submissions at the hearings asserted that King was a socialist or at the very least a fellow traveler of Communists. The minority also argued that King’s anti–Vietnam War stance, his advocacy for Communist China’s United Nations membership, and his antinuclear activism were such controversial and subversive positions as to cast doubt on his patriotism. Because King “aroused the emotions of the American people,” time had to “temper” those emotions before Congress could properly judge his place in history.

In short, opponents insisted that King had “not preserved beyond reproach his place in history.” The fourth and fifth arguments related to the holiday’s structure. The dissenters asserted that national holidays did not truly exist as Congress could only legislate for federal employees. Therefore, responsibility for public holidays fell to the states to decide. Finally, should they be forced to honor King, the dissenters favored not a paid holiday but an unpaid memorial day. This alternative, first proposed in the Senate by Massachusetts Republican Edward Brooke in 1968, remained ever-present throughout the debate. Having this option enabled opponents to concede, if necessary, that King deserved remembrance without having to agree to a full holiday.

However, advocates seeking the prestige of a paid holiday thought an unpaid memorial day unacceptable. Though the minority conceded King made an “outstanding contribution…to the cause of civil rights for black Americans,” such phrasing confined King’s influence to Black Americans only. Another minority report, authored by opponents from the House committee, reached similar conclusions. Despite these reservations, both committees recommended the legislation to Congress.

The interrogation of King’s reputation was typical of a pattern noted by Derek H. Alderman, scholar of the phenomena of street naming. Since 1968 U.S. cities have named 955 streets after King. Alderman argues that successful commemorations must concern a legitimate historical figure, have resonance with the contemporary public, and be hybrid enough to appeal to more than one group. Whether King embodied these three factors appeared doubtful to some, but his supporters vigorously maintained he did. King boosters and detractors debated King’s merits according to these criteria, even if not explicitly stated as such. Yet, as architectural historian Dell Upton writes in What Can and Can’t Be Said, monument builders must contend “with the continuing dominance of white supremacy.”

The final word would be given by a body that was overwhelmingly white and male, and which included former—and some still practicing—white supremacists. The first demonstration of who had the final word came in 1979. On November 13, 1979, the House began to debate the bill. It did so for a mere forty minutes. The proposed January 15 holiday—on King’s birthday—fell five votes short of the two-thirds majority required (252 to 133) to pass without amendment under suspension of the rules (a procedure usually reserved for noncontroversial bills). Only one Republican, Ben Gilman of New York, spoke in favor.

The House resumed debate on December 5, when the legislation’s sponsors hoped to succeed with a simple majority. This attempt appeared promising, but without a two-thirds majority, opponents could sabotage the bill with amendments. That is exactly what happened. When the bill came to a vote, Illinois Republican Robert McClory proposed an amendment to move the proposed holiday to the third Monday in January, conforming with the 1968 calendar reforms. McClory’s amendment still allowed for a paid holiday; he argued that a Monday holiday saved taxpayer money and limited disruption to industrial productivity. Having a long weekend would also allow citizens more time to prepare for the day. It passed by a majority of 291 to 106 as 217 Democrats (80 percent) and 74 Republicans (45.5 percent) voted in the affirmative. Notably, 72 percent of Southern Democrats approved the holiday, a figure unimaginable fifteen years prior. Of Southern Republicans, however, 60 percent opposed the holiday. At face value, this vote illustrates the shift in the South’s political alignment since 1964. Southern Democrats voted to honor an African American, while Southern Republicans, the first of their like since Reconstruction, voted against. However, the alignment had not changed enough to protect the bill from amendment.

The House appeared to deliver a strong endorsement. However, Robin Beard, a conservative Republican from Memphis, proposed to move the holiday again, to the third Sunday of January. He claimed that this honored King while being “sensitive to tremendous costs in productivity.” The Sunday observance would therefore be an unpaid memorial day, not a federal holiday. Contradicting its affirmation of the McClory amendment, the House voted 207 to 191 in favor of the Sunday amendment. Tellingly, fifty-two Democrats who voted for Monday then voted for Sunday. Southern Democrats shifted most: thirty-one changed from Monday to Sunday, and twenty-two who had voted against Monday voted for Sunday. That Georgia Democrat Larry McDonald, a fierce anti-Communist King critic, took the latter course suggests that some who voted for the Sunday amendment did so not to honor King but rather to sideline his legacy with the minimum recognition possible.

The Republicans turned out to be just as noncommittal. Fifty-two of the seventy-four who originally voted for Monday switched. Seventy of the seventy-three who had voted no to Monday also voted for Sunday. The fact that most Republicans who voted no to a Monday holiday supported a Sunday holiday was either an acknowledgment that King deserved at least some recognition or a cynical attempt to relegate the nation’s memory of him to a forgettable Sunday. The destructive Sunday amendment conformed with a pattern whereby opponents of civil rights memorials shunted them to the sidelines of civic society where they could be safely ignored. A memorial Sunday holiday had no more significance than Mother’s Day or Father’s Day.

In this context, holiday proponents perceived those who voted yes to Monday and no to Sunday as possessing superior civil rights credentials. Rejecting the amendment, the Congressional Black Caucus withdrew the legislation. Bronx representative Robert Garcia stated that the Congressional Black Caucus would not settle merely for “a commemorative day.” Due to the failure of the House bill, the Senate did not proceed to a vote on its own version. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution summed up the stalemate in an editorial: “We deeply resent the insult presented Dr. King’s family and admirers by the House of Representatives.” It argued that despite, or perhaps because of, centuries treating “black people as second-class citizens,” the House voted for a “second-class holiday.”

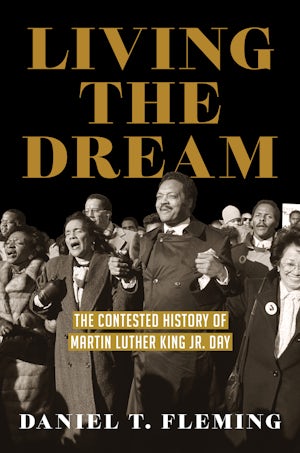

From Living the Dream: The Contested History of Martin Luther King Jr. Day by Daniel T. Fleming. Copyright © 2022 by Daniel T. Fleming. Published by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher.