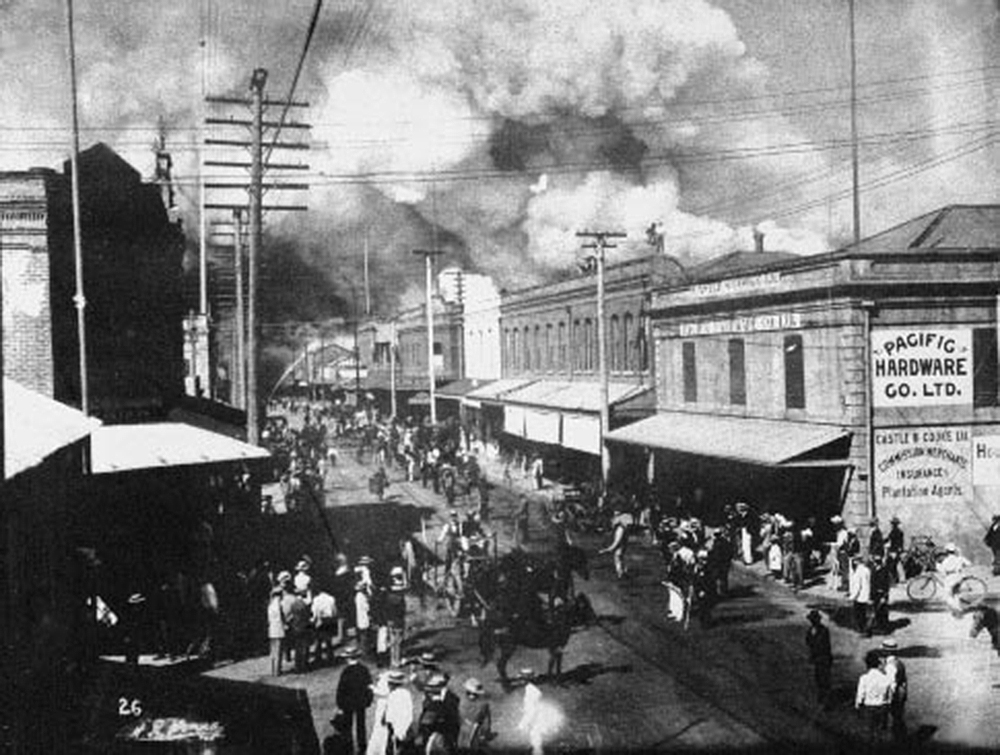

View of Main Street, Honolulu, Hawaii, c. 1900. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection.

On the morning of December 8, 1899, Yuk Hoy, a forty-year-old bookkeeper, awoke in his bed to the flash of a high fever and a mysterious swelling in his thigh. Unable to do much more than mumble, he laid his head down and drifted in and out of sleep, largely ignored by the other men crammed into a windowless room of a two-story flophouse in Honolulu’s overstuffed Chinatown. Having arrived just weeks before from his native China, Yuk Hoy had few friends in the bustling city, and his absence over the following days went unnoticed at the general store on Maunakea Street where he worked. Only his increasingly frantic cries alerted others to the misery of his existence. Woken by his wails, a man named Fong, who lived on the same floor, stumbled in darkness to find him trembling in a litter of straw, his body quivering, as Fong would later describe it, “like the branches of a tree in thunder and lightning gone crazy.”

Fong lifted the man and made his way by moonlight along the unpaved streets of Chinatown to the office of Dr. Li Khai Fai on River Street one block away. Tall and fiery, Dr. Li was one of the few Chinese doctors trained in Western medicine that could be found in Hawaii. Dr. Li was alone when Fong burst in and laid Yuk Hoy in front of him. The man was covered in feces and vomit and raved in apparent madness. Dr. Li struggled to hold his new patient still, all the while wondering how he was still alive. A finger to his wrist revealed a racing pulse, as if the body was facing an internal terror, while his forehead was so warm to the touch that Dr. Li fought the instinct to pull his hand away. When Yuk Hoy yelled, his screams sounded wet, as if emerging from below the sea. The man’s skin was pocked with black spots and open red sores. The lymph nodes in his thigh were so swollen that it looked as if his leg had been pumped full of air and was at risk of floating away. A mixture of blood and foam began leaking out of his mouth, a sign of ruptured blood vessels, and he soon fell into a coma from which Dr. Li knew he would never recover.

He was one of only a handful of people then living in Hawaii who had seen the full power of the disease killing the man in front of him, and his knowledge had come at great personal cost. At the age of nine he had watched as his father, whose conversion to Christianity had led others in their village in southern China to call him a “running dog of the white devils,” came under attack by a mob that stoned him to death in the street. His mother fled with her four children to Hong Kong, and at the age of sixteen Li enrolled at the Canton Medical School, a school of Western medicine founded by an American doctor from Ohio. There he met his future wife, Dr. Kong Tai Heong, who in time would be at his side to witness death on a scale neither could have imagined.

Dr. Kong was widely seen as her husband’s intellectual superior. Left in a basket on the steps of a Lutheran mission in Hong Kong as an infant with nothing more than a pin bearing her name, she had grown up helping German nuns care for other children in her orphanage. They, in turn, helped her apply to the Canton Medical School. There she was known as the most brilliant student in her class, and, with Li, spent her off hours tending to victims of the epidemic ravaging Hong Kong that left hospitals reporting a 95 percent death rate. The pair graduated from medical school one June morning and were married in a Lutheran chapel the same afternoon. The following day they boarded a steamship headed to Hawaii, drawn by its promise of paradise after the hell they had seen.

There was no doubt in Li’s mind that the disease that he had prayed would never follow him had now come ashore. Since arriving in Honolulu, he had built up his practice ministering to poor Chinese immigrants who were suspicious of the small but powerful group of white merchants and missionaries who, two years earlier, had overthrown Hawaii’s monarchy in hopes of American annexation. Any cooperation with the new government would be seen as a betrayal and put him at risk of meeting the same fate as his father. Despite that danger and the late hour, Dr. Li summoned Dr. George Herbert, an English physician who worked for the Board of Health. By the time he arrived, Yuk Hoy was dead. Dr. Herbert called in two other colleagues, and, with Dr. Li, prepared the examining table to conduct an autopsy in the small hours of the night.

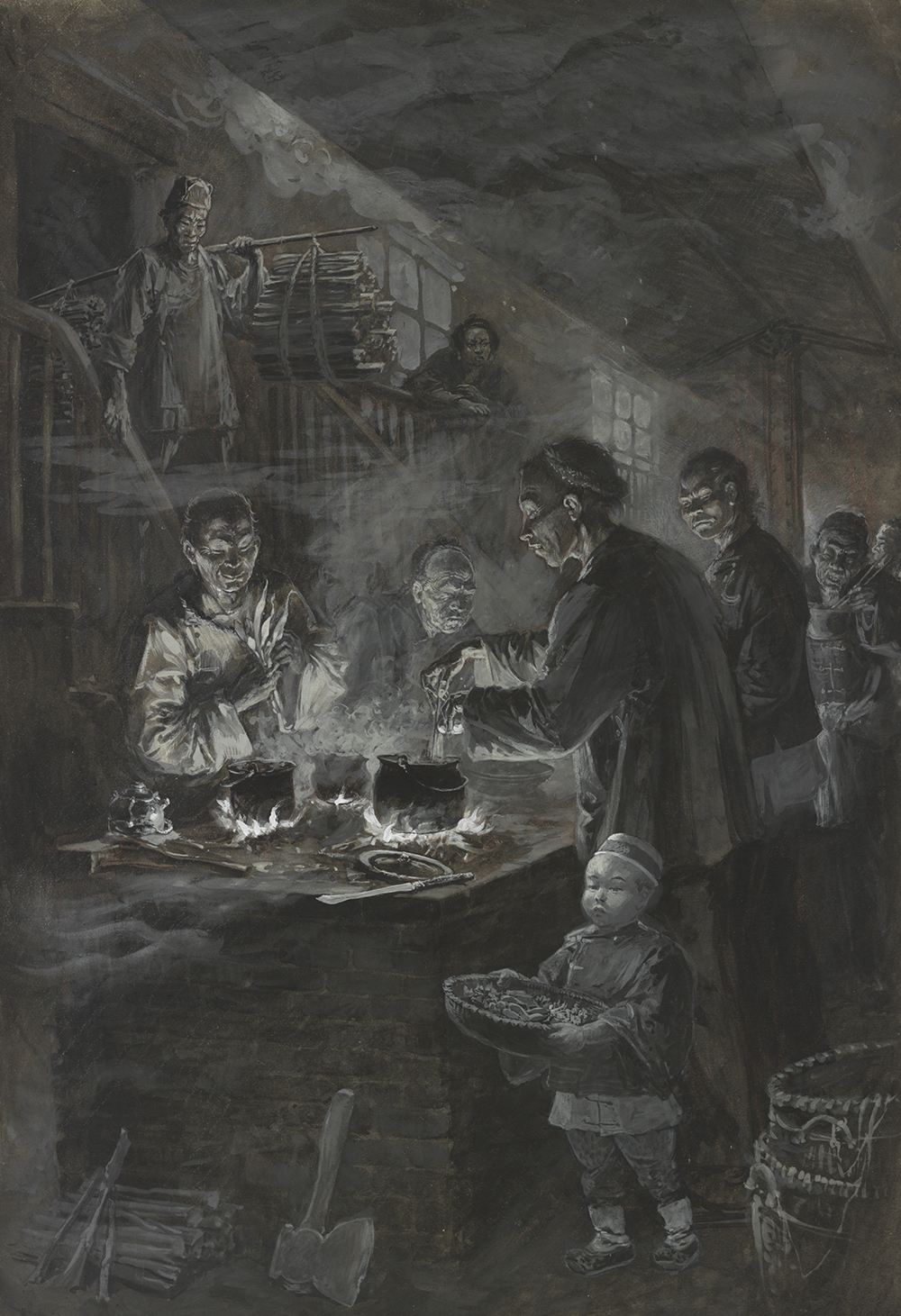

By the flickering light of kerosene lanterns, the team of white doctors stood shoulder to shoulder and watched as Dr. Li opened the body and peeled back its skin to reveal signs of extensive internal hemorrhaging. Dr. Walter Hoffman, a young German doctor just four months into his job as Honolulu’s first bacteriologist, stepped forward to take a sample of tissue from the glands of the dead man. His laboratory across town was the only place on the island that could confirm what every doctor assembled that night now believed: for the first time in history, bubonic plague had reached Hawaii, bringing with it the capacity to kill everyone they loved in a matter of days.

Bubonic plague appeared in the rural province of Yunnan in south central China in the late 1870s, where it festered for nearly two decades before making its way across the globe. By 1893 it had reached the city of Canton, where, in the words of one observer, it killed thousands of people “like plum blossoms in a late frost.” From there, the disease traveled along the Pearl River to Hong Kong, and then on board steamships to the wider world. In China, some ten million people died within a span of five years; by the end of 1910, another five million would perish as plague emerged in India, Australia, Scotland, and North Africa, sparking fears that the Black Death—a fourteenth-century worldwide outbreak of plague that in some areas killed 60 percent of the population—had returned.

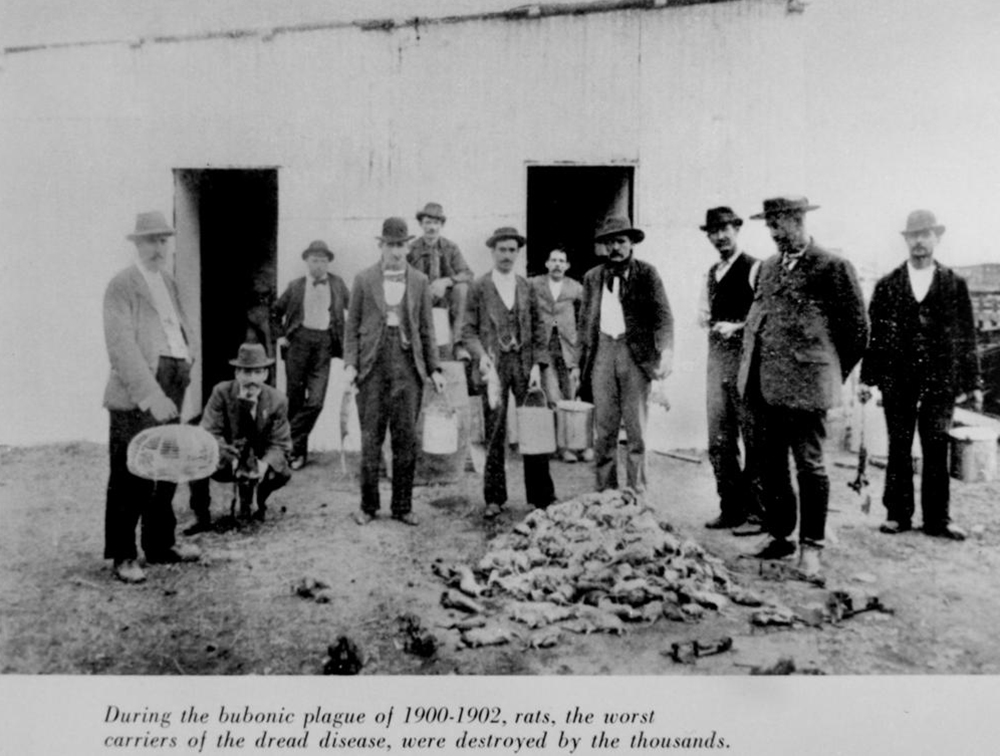

In 1894 a tiny, rod-shaped bacterium known as Yersinia pestis was identified as the source of plague, but beyond that little else—how the disease spread, who was most likely to contract it, or whether any medicines could dent its progress—was known.

Prejudice often filled in the blanks. Puzzled by the fact that few upper-class foreigners living in colonial compounds in Hong Kong and India caught the disease even as thousands around them succumbed, some public health officials drew the pseudoscientific conclusion that those with European ancestry had somehow developed immunity to plague and pointed to their survival as proof of racial superiority. In 1897 the powers of Europe, nervous at the thought of allowing someone bearing the disease across their borders, agreed to impose travel restrictions on goods and people that codified this theory into law, allowing upper-class whites free passage from plague-stricken areas while denying entry to everyone else.

With its arrival in Chinatown, the path of plague in Honolulu seemed to confirm what many white Hawaiians already suspected. On the night of Yuk Hoy’s death, another Chinese bookkeeper was found dead with the same symptoms just blocks away. Five additional victims were discovered over the next four days, all of them Chinese men except for one twenty-four-year-old man who had days before arrived from the Gilbert Islands, some two thousand miles away. The Board of Health ordered a five-day quarantine of Chinatown, trapping an estimated ten thousand men and women in the space of eight city blocks. Armed guards stood with fixed bayonets at the edge of the district, intent on keeping anyone infected with the disease from spreading it beyond its borders. A mob soon gathered outside the office of Dr. Li, the man they now blamed for their confinement. The doctor jumped on his bicycle and raced away, barely escaping with his life. As rumors of an imminent riot bubbled through the city, the Board of Health counted down the days until it could lift the quarantine, hoping that their nightmare would soon end.

On the day that the barriers were set to come down, a German teenager named Ethel Johnson developed a suspiciously high fever. The modest Johnson home was on Iwelei Road, a street just outside the quarantine zone that bent from the edge of Chinatown toward the harbor. Wagons filled with human waste, collected from the toilets of the district, were a common sight traveling past the house en route to a seaside dump. A team of doctors sent to the girl’s home found suspicious lumps in her armpits and groin, leaving them no choice but to identify her as a possible case of plague. A phalanx of soldiers formed a barrier around the Johnson home, blocking anyone from entering or leaving the residence, despite the protests of a physician at the Board of Health who found it an insult to group the girl together with “Hawaiians, Japanese, and Chinese, an act which would defile the dignity of [her] whiteness, the people who control and rule this archipelago.”

Ethel Johnson died five days later. Other deaths followed in rapid succession, like dominos spreading across a table. With the quarantine ineffectual, the Board of Health panicked, consumed by the prospect of the islands becoming overwhelmed by a disease that seemed to have no cure. The men then turned to what even they agreed was a solution that would have seemed crazy six weeks before: fire. No science could point to its efficacy, and no city had ever tried it before, but the prospect of burning the disease away satisfied some deep urge.

Nathaniel Emerson, the eldest member of the board, stood at a podium before the group of men who effectively ruled all of Hawaii. The son of missionaries from New England, he was one of the few white adults who had been born on the islands and had sailed east to attend Williams College in his parents’ native Massachusetts. While he was there, the Civil War broke out, and he enlisted in defense of a nation to which his home did not technically belong. Scars from Confederate artillery shrapnel that wounded him during the Battle of Gettysburg still traced his body. He returned to the islands years later, after earning a medical degree at Harvard and then working as a private physician in Manhattan. At the age of sixty, he no longer feared the social consequences of his actions and prided himself on his independence.

“I am willing to go right ahead and take all the responsibility and burn anything and do anything that is necessary,” he told the men seated before him. One by one, his colleagues agreed. They would burn every building suspected of harboring plague to the ground immediately, regardless of the owner’s wishes, praying that fire could do what medicine so far could not. On the morning of Saturday, December 31, local firemen ignited a pair of two-story buildings where a man named Ah Kau had been found dead of plague a few days before. The buildings were home to eighty-five Chinese, Japanese, and Hawaiians, who were all taken to a makeshift quarantine station that resembled a prison. English-language newspapers cheered the new policy, with the Commercial Advertiser calling it “fighting the devil with fire.”

Fire was the city’s last hope, and no one knew if it would work. No New Year’s Eve celebrations were held in Honolulu that evening, the final night of the nineteenth century. The only sound in the deserted city’s streets was that of a Portuguese band, playing the wailing notes of a funeral dirge.

Excerpted from Black Death at the Golden Gate: The Race to Save America from the Bubonic Plague by David K. Randall, published by W.W. Norton. Copyright © 2019 by David K. Randall. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.