Excerpts from McClure’s Magazine, November 1909, and the San Francisco Chronicle, December 14, 1886.

In 1909 McClure’s Magazine published an article exposing a dark secret in New York City. Muckraker George Kibbe Turner reported that men (many of them Jews) were luring girls and young women into the sex trade against their will as part of the so-called white slave trade:

The average life of women in this trade is not over five years, and supplies must be constantly replenished. There is something appalling in the fact that year after year the demands of American cities reach up through thousands to the tens of thousands for new young girls. The supply has come in the past and must come in the future from the girls morally broken by the cruel social pressure of poverty and lack of training. The odds have been enough against these girls in the past. Now everywhere through the great cities of the country the sharp eyes of the wise cadet are watching, hunting her out at her amusements and places of work. And back of him the most adroit minds of the politicians of the slums are standing to protect and extend with him their mutual interests.

Turner’s McClure’s article alarmed Jews who believed that anti-Semitism lay behind the focus on Jewish sex traffickers. Jewish organizations, including B’Nai B’rith, helped counter the accusations by starting their own anti-sex-trafficking crusades. Their campaigns shifted public opinion a bit, as evidenced by the writings of Clifford G. Roe, assistant state’s attorney of Cook County, Illinois. “The good Jews,” wrote Roe, know other Jews were involved in white slavery “and feel keenly the unspeakable shame of it.” He quoted an American Hebrew editorial stating, “If Jews are the chief sinners, it is appropriate that Jews should be the chief avengers of the dishonor done to their own people, and in many cases to their own women.”

At the same time, Turner’s horrifying depiction of a sex-slave market spurred Judge Thomas O’Sullivan to begin a grand jury investigation, appointing oil magnate John D. Rockefeller to be its foreman. After months of searching, in 1910, the grand jury found there was no evidence for “an organized traffic in women for immoral purposes” in New York’s streets. The verdict should have been the end of the sex-trafficking hysteria, but more than a century later a similar lack of evidence has not prompted any slowdown among anti-trafficking campaigns or a decline in their popularity.

Since the nineteenth century, sex-trafficking reformers have come from many different groups, all with different agendas. “In contemporary anti-trafficking campaigns,” scholar Elizabeth Bernstein argued in 2010, “it is ironically secular feminists who are advocating for family values, together with a new middle-class contingent of evangelical Christians.” Both groups, says Bernstein, share “the conviction that sexuality should be kept within the confines of the romantic couple serves to cement a political alliance between ideologically disparate constituencies.”

Anti-sex-trafficking campaigns have never been proved to be effective in eliminating sex trafficking. They have clearly been successful in generating money and attention for other causes as various as women’s suffrage, labor laws, prostitution reform, religious groups, and immigration reform, however. These other agendas often crowded out the women at the center of the fight. For the most part, prostitutes’ voices have been erased from history, aside from in vice reports and a few memoirs, so the history we end up with is of people suppressing prostitution, not those engaged in it.

Prostitution has not always been illegal in the U.S. During the colonial era, prostitution was basically legal, although sometimes vagrancy laws and similar statutes that did not specifically target the sex trade were used to arrest prostitutes. There were no federal anti-prostitution laws before 1910.

Prostitution had a quasi-legal status. Laws governing it differed from state to state and sometimes from city to city. It was tolerated in the nineteenth century. Many cities had flourishing red-light districts—even though by that time in many states and cities prostitution was technically illegal—such as New Orleans’ Storyville and Chicago’s Levee districts. The criminalization of prostitution was directly linked to anti–white slavery campaigns. It wasn’t until 1919 that a federal law criminalizing prostitution was passed. And it took until 1925 for all existing states to enact their own anti-prostitution laws.

Anti-trafficking campaigns were an effective way to discriminate against all “undesirable” ethnic groups. Italians were targeted, as were the Chinese. One of the earliest organized campaigns against sex trafficking in the United States centered on “immoral” Chinese women who were supposedly leading white men and boys on a dangerous, debauched path and spreading syphilis as they went.

In a response to the so-called Yellow Slavery, California congressman Horace Page drafted a law to “end the danger of cheap Chinese labor and immoral Chinese women.” The anti-immigrant, anti-Chinese Page Act was passed in 1875, setting the template for over a century of legislators using human-trafficking laws to discriminate against unpopular groups. The measure prohibited the transportation of immigrants from China, Japan, “or any Oriental country” to the U.S. for “lewd and immoral purposes,” including “prostitution.” The law also made it illegal to transport any Asian people for involuntary work, but prostitution was singled out and punished the most harshly. Asian prostitutes were also banned from immigrating to the U.S. The Page Act was one of the first laws to conflate trafficking with prostitution.

The hearings on immoral Chinese prostitutes in Congress that had begun during discussion of the law were still taking place two years after the Page Act passed. Dr. H.H. Toland, a member of the San Francisco Board of Health, testified before a congressional committee that Chinese prostitutes coerced boys into their brothels, infecting them with syphilis and gonorrhea. He blamed Chinese prostitutes for 90 percent of such cases among boys in the United States. Boys wouldn’t be as likely “to take the liberties with white women as they do in Chinatown,” Toland added. Nor would white prostitutes allow such young boys in their brothels, he argued.

While lawmakers used human trafficking to further racist policies, women’s organizations campaigned against it—and borrowed some of the lawmakers’ racist rhetoric—for political power during a time when women didn’t have the vote. Bernstein explains that feminists benefit from anti-trafficking rhetoric because it can allow them to increase “their own power in [the] domestic sphere [and] heterosexual relationships—a power that the global sex industry is understood to erode.” Anti-trafficking campaigns were a part of a broader movement of women’s activists gaining political power denied to them by asserting their moral authority of the domestic sphere. The white slavery campaign was entwined with the other movements we consider central to first-wave feminism: temperance, voting, and marriage reform.

One of the earliest women’s groups to argue against prostitution was the New York Female Moral Reform Society, founded in 1834 to close down brothels and end prostitution. Although the group didn’t explicitly say women were trafficked, they believed most women had not chosen to work as prostitutes but had become duped into the profession by men. The group hired “missionaries to try to convert prostitutes in city jails and hospitals [and] visited brothels…praying, singing, and writing down the names of customers,” according to historians John D’Emilio and Estelle Freedman. These groups were both fighting a moral war—and hoping to gain Christian converts.

But it wasn’t until the late nineteenth century, when women’s organizations in the United States—inspired by their sisters in England—began mobilizing specifically against forced prostitution as part of their social-purity campaigns. These anti-prostitution campaigns usually presented all prostitution as sexual slavery; they assumed no woman would freely choose to be a prostitute. Vice reports tell an interesting story, however. These reports contain interviews with prostitutes, demonstrating that the white slavery narrative wasn’t necessarily accurate. As historian Paul Boyer writes, “From the perspective of many of the women themselves…the decision [to become a prostitute] represented a liberating escape from bondage.” One woman said she became a prostitute because she “was always fond of life. Married a dead one; he never goes out.”

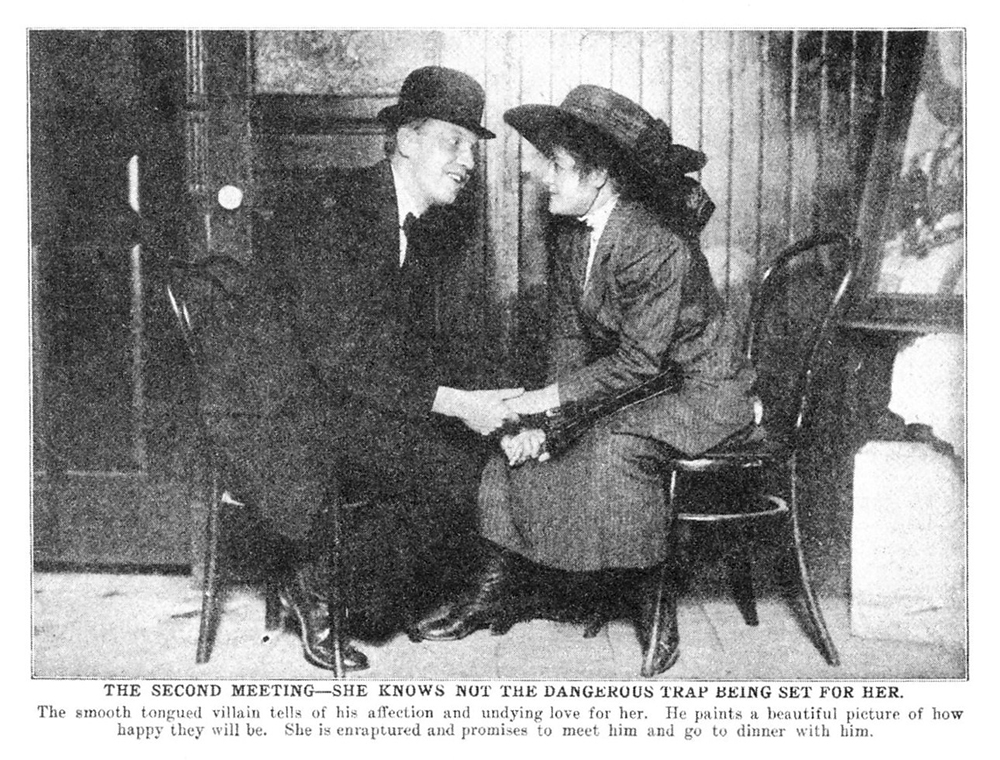

Groups like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union presented the archetypal white slave as a naive, virginal, young white girl who is whisked away into a life of prostitution by an evil man, usually foreign or African American but sometimes white. According to D’Emilio and Friedman, the WCTU “perpetuated the view that prostitutes had been victims of male deception, rather than freely choosing their trade.” Many women’s organizations were crusading against vices such as alcohol, and the white slavery campaign fit nicely within their platforms.

The WCTU was interested in campaigning against white slavery because it wanted to make prostitution illegal at a time when prominent physicians including William Sanger were arguing that prostitution should merely be regulated and prostitutes tested for venereal disease. Prostitution was threatening the sanctity of the marital home, according to the WCTU, because it symbolized changing gender roles and loosening restrictions on female sexuality.

White slavery was also used to argue for women’s right to vote. The idea seems odd, but Francis Willard of WCTU, according to historian Brian Donovan, asserted that “ ‘white slavery’ offered an unambiguous example of male cruelty and the need for the moral influence of women.” Similarly, Jane Addams wrote in her 1912 book, A New Conscious and Ancient Evil, “It is quite possible that an equally energetic attempt to abolish white slavery will bring many women into the Equal Suffrage movement, simply because they too will discover that without the use of the ballot they are unable to work effectively for the eradication of a social wrong.”

At the same time, ministers were zealously preaching against white slavery, taking to the streets in large cities throughout America. During the 1906 National Purity Congress in Chicago—an annual conference that attracted doctors, ministers, and scholars from around the world to share ideas about combating vice—the Reverend Sidney C. Kendall ferried missionaries and police officers to the city’s brothels, asking prostitutes if they were Christian. Three years later, British evangelical preacher Gypsy Smith led a march of thousands through Chicago’s red-light district while singing religious songs. “It’s going to be a great demonstration for Jesus,” he predicted. Ministers headed up vice organizations that worked hand in hand with police to root out white slavery. Yet brothels continued to operate, and Smith and others continued to moan about white slavery. Another march through Chicago’s red-light district was organized a month after Smith’s.

More anti-sex-trafficking legislation continued to be sponsored, thanks in part to the endless moralizing of the time. In 1903 a law was passed penalizing people who brought women to the U.S. for prostitution. Another law, implemented four years later, allowed immigrants working as prostitutes to be deported. But it wasn’t until 1910 that these new laws began to specifically target alleged homegrown traffickers. That was when an anti-sex-trafficking act called the White Slave Traffic Act (known as the Mann Act) was passed, penalizing the transport of women and girls across state lines for immoral purposes. The Mann Act caused many people to be unfairly accused of sex trafficking, particularly consensual sex workers and African American men traveling with their white girlfriends. Famous African American boxer Jack Johnson was arrested under the Mann Act in 1912 after his eighteen-year-old white girlfriend Lucille Cameron (who happened to be a former prostitute) traveled from Minneapolis to Chicago to visit him. She refused to testify against him, so assistant U.S. attorney Harry A. Parkin, determined to take down Johnson, dispatched men from the Bureau of Investigation to get another woman to speak against him. They found twenty-three-year-old prostitute Belle Schreiber, who frequently traveled with Johnson. Her testimony led to Johnson’s successful prosecution under the Mann Act.

Around the time of the Mann Act’s passage, the anti–white slavery campaign reached its apex, thanks to the lurid tales of white slavery being spread across popular culture. These stories proved a great way to sell newspapers during an era rife with media competition. In some of the seedier “sporting news” papers, writers named the brothels, their addresses, and details about the prostitutes on offer; these condemnations also gave men information on where to find prostitutes. Newfangled films also benefited from white slave hysteria. One of the most popular movies in the 1910s was the movie Traffic in Souls (1913), which purported to show a dramatization of actual white slavery in America. Set in New York, the film focused on a young woman who was lured into white slavery ring run by a corrupt social-purity reformer.

Anti–white slavery campaigns at the beginning of the twentieth century did succeed in closing down red-light districts and helping make prostitution illegal. Prostitution continued, but it morphed from brothel-based prostitution into women working as call girls and on the street.

By the late 1920s and early 1930s, anti–white slavery campaigns fizzled out—perhaps because they had been successful in achieving their legislative aims. Thanks to the failure of the temperance movement, there was also a realization among reformers and politicians that laws couldn’t change behavior, according to Boyer. Reformers saw that sex couldn’t be controlled in cities like it could be controlled in smaller towns, Boyer argued, because the communities in cities were too large for there to be damage to an individual’s reputation through public shaming. Anti-trafficking campaigns mostly disappeared from society in the 1930s to 1960s. In the 1960s, sex workers began organizing, and some prominent individuals and organizations such as the ACLU argued for legalization of prostitution.

But anti-sex-trafficking campaigns came back with a vengeance in 1979 when sociologist Kathleen Barry’s Female Sexual Slavery was published. The book helped spark a new anti-trafficking movement in the 1980s and 1990s. Barry defined female sexual slavery broadly, stating that it included any sexual situation

where women or girls cannot change the immediate conditions of their existence; where regardless of how they got into those conditions they cannot get out; and where they are subject to sexual exploitation and physical abuse…The definition…extends to the condition of women who are the objects of wife battery and girls who are incestuously assaulted. In some cultures female sexual slavery takes the form of forced and arranged marriage and includes veiling and seclusion of women in the home.

In 1988 Barry cofounded the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women, which held that no consensual prostitution exists because “prostitution victimizes all women” and that any travel for prostitution was sex trafficking. The coalition’s campaign was called an “abolitionist” movement by Jo Doezema, a member of the Network of Sex Work Projects, and other scholars. It spurred a raft of anti-trafficking feminist groups, which helped shape the narrative of prostitution as sex slavery.

These campaigns had an “implicit racism,” according to Doezema, who argued that they presented third world women as “poor, naive, and ‘unempowered,’ ” as if these “women from third world or former communist countries were unable to act as agents in their own lives or to make an uncoerced decision to work in the sex industry.”

Not all groups conflated sex trafficking and sex work. By the 1990s, other organizations, including the Global Alliance Against Trafficking in Women, began their own campaigns emphasizing that not all sex workers were trafficked. Unlike their predecessors, these took great pains to distinguish consensual sex work from forced sex work.

In the 1980s and 1990s, anti-trafficking campaigns became a favorite not just of feminists but also of Republicans and the religious right. Many Christian groups argued that consensual prostitution did not exist. Sex-trafficking victims continued to be presented as virginal, innocent young women, but no longer just white or Chinese—although both groups remain a major focus to this day, as the massage parlor stings in Florida’s Treasure Coast have shown. These stings—which have led to the arrest of several Chinese massage parlor owners and workers, as well as hundreds of customers, including Patriots owner Robert Kraft—were initially branded as human trafficking by the police and most of the press. Yet nobody has been charged with human trafficking, and so far only a few women have been identified as victims.

Over a century ago, after the arrests of madams and closures of brothels in Chicago on October 5, 1912, prostitutes took to the streets, according to journalist and historian Karen Abbott.

Two thousand of them formed a tawdry procession down Michigan Avenue, wearing high feathered hats and plummeting gowns, faces streaked in crimson rouge, bare legs goose-bumped in the cool fall air. They sidled up to society women and winked at their husbands, sweeping long painted nails along the blushing men’s backs…Knocking on doors, they explained they had been driven from their homes. Were there any rooms available?

The only rooms on offer were from vice reform organizations. No woman accepted. Similar marches went on for days, but the women never did get their homes back. The red-light district was shut down. The women were “saved.” But what were they being saved from?