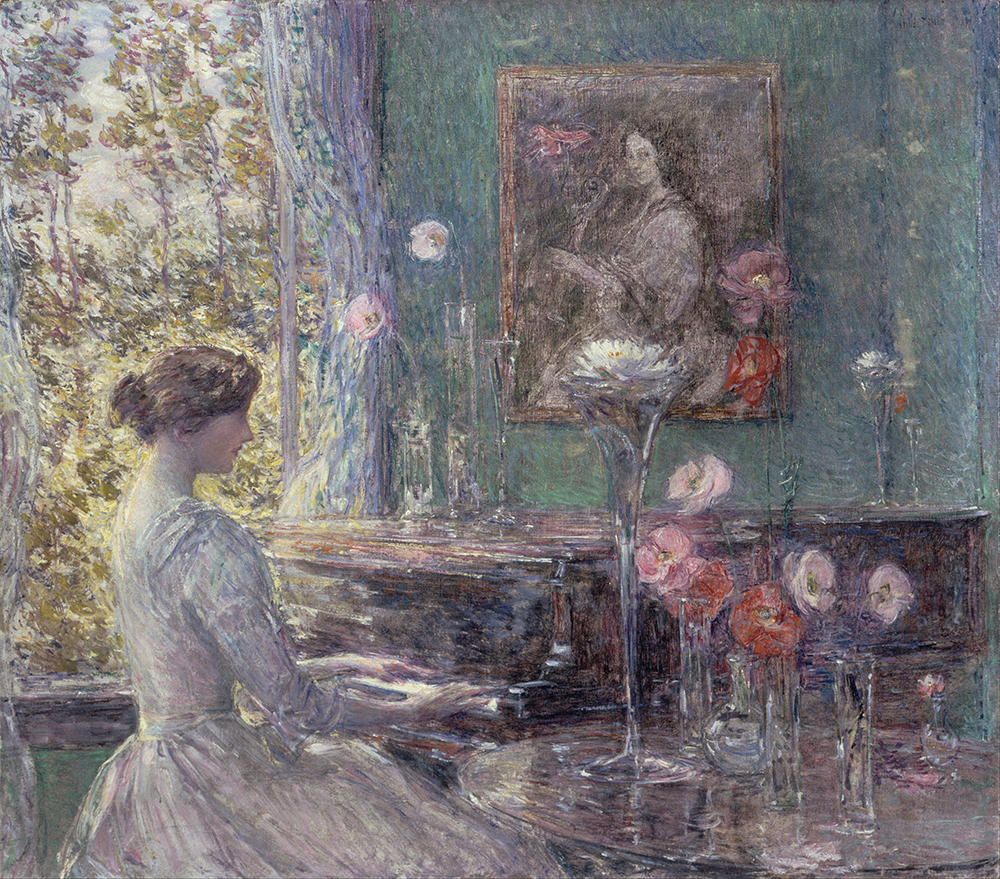

American Beauties, by Harrison Fisher, 1907. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The popularity of the magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book in the nineteenth century was due to more than its display of sumptuous clothing and decadent jewels. Its appeal had a lot to do with its effort to create what the historian Benedict Anderson might describe as an “imagined community” of white middle-class Protestant women. In the midst of the massive social upheaval of the mid-nineteenth century and the redefinition of just who was an “American,” Godey’s Lady’s Book was a guidepost for such women. Conjuring the spirit of The Spectator across the Atlantic, the publication treated Christian ladies to burgeoning middle-class lighthearted entertainments. It suffused its merriment with lessons in the necessary moral principles for proper conduct. The difference, of course, was that while The Spectator focused its moralizing rhetoric on the cultivation of men, Godey’s Lady’s Book focused on teaching girls and young women the rules of polite, white Christian society.

Sarah Joseph Hale, as the publication’s editor, wanted nothing to do with fashion plates for women of leisure. But questions involving said women’s moral advancement were of great interest to her. She found it no less than her duty to instruct her female readers as to how to behave properly before the eyes of God. A central theme as it pertained to questions of correct conduct was “temperance” in eating and drinking. Articles on this topic often reminded women that they were the moral guardians of the home and the custodians of cuisine. Thus, it was their responsibility to check the indecencies, or indulgences, to which men were prone. In an article from 1839, written by a Mrs. Sigourney but featured in a section called the “Editor’s Table,” the author writes, “Excesses are too often indulged in…but can any man devise a more effectual check upon them than the presence of a woman?”

Within the many and overlapping Protestant reform movements of the early nineteenth century, women came out in force. If the most prominent figures in these movements were men, women were the true foot soldiers for the cause. Middle-class women outnumbered men among converts in the Second Great Awakening, and they were also the main trumpeters of temperance and dedicated diet reform. So it was that in the 1830s, when Louis Godey launched his lady’s magazine, it was only natural that he should choose to explore, and exploit, a topic that the recently christened middle-class women held dear to their hearts. The genius of Godey’s Lady’s Book lay not simply in its ability to pick up on the era’s spirit of reform. Godey’s also enticed a newly hatched generation of women of means with the fripperies and frills of luxury, which would have been out of reach for the average American woman a generation prior.

What appeared in Godey’s under Hale’s guidance was not just an increase in the number of articles and essays on the proper amount to eat and drink to satisfy God, health, and the pursuit of beauty. These three topics had been addressed before Hale took over as editor. Under Hale came a fourth and previously little-considered aspect to being a right-minded, middle-class Protestant woman: the need to prove one’s racial superiority as an Anglo-Saxon.

Theories of Anglo-Saxon supremacy can be traced to sixteenth-century England, coinciding with the Protestant Reformation. In their earliest manifestation, these theories were used to justify Henry VIII’s bid to secede from the Norman papacy. Those favoring secession had argued that the original English people descended from a pre-Norman Germanic tribe known as Anglo-Saxons, a freedom-loving people who had originated civilizations, free institutions, and equitable laws. The goal was to make a claim for ancestral difference, and thereby socio-legal independence, from the papacy. Although superiority was implied, this use of the term Anglo-Saxon preceded the use of the term race.

Yet the idea of Anglo-Saxon supremacy would resurface under a new racial and religious guise in the late eighteenth century. By 1776, a number of men in England were declaring themselves Anglo-Saxons. The firebrands were outraged this time not with the Norman papacy so much as the Norman Conquest itself, which they saw as evidence of foreign rule. The names of these rebels are mostly forgotten. But their ideas resonated forcefully with others of purported English extraction who felt similarly aggrieved by foreign rule—namely, the Americans. As a result, many of their central tenets were co-opted, refashioned, and promoted during the height of race making in America.

For the first time, gradations within whiteness were being devised. As the nineteenth century approached, hierarchies and distinctions between elite whites (of Anglo-Saxon and implied Protestant heritage) and lowly whites (who were neither Anglo-Saxon nor Protestant) were articulated. In other words, there were now different categories of white people.

Perhaps predictably, given the racial politics of the time, the way to ascribe racial inferiority to another group of Europeans was to align them with one of the “colored races.” And so, beginning in the nineteenth century, the authors of new racial theories claimed that Anglo-Saxons were the “pure” white race, whereas other Europeans, principally the Celtic Irish, were deemed an inferior or hybrid European race. These hybrid European racial inferiors were thought to be either “part African” or “part Asiatic,” depending on the fancy of their creator.

British ethnologist James Cowles Prichard is of interest here for his treatment of the Irish as alternately “part African” and “part Asiatic.” Prichard was well known as a theorist of human variability. One of his most widely read works, Researches into the Physical History of Mankind, was written in 1808, published in 1813, and polished over successive iterations between 1836 and 1841. It was in the 1836 and 1841 versions, as well as his 1831 text The Eastern Origin of the Celtic Nations—all of which followed his election to the Royal Society—that Prichard made notable contributions to theories of intra-white racial distinction.

The racial lore of the time suggested that the English were a stouter breed of Anglo-Saxon than the Americans. By the mid-nineteenth century, this supposed general spareness of constitution, especially among women, would become a basis for extolling native-born Anglo-Saxon Protestant American women.

Sarah Hale had taken over the editorship of Godey’s Lady’s Book in the midst of these massive transformations in American religious and racial identity. After 1836, both Hale and the magazine reflected the times. As early as 1830, Godey’s Lady’s Book had spoken the language of temperance, urging women to curtail the amount they ate in the interest of God, health, and beauty. Upon the arrival of Hale some six years later, Godey’s expressed a growing concern about the racial propriety of fatness.

The year Hale arrived at Godey’s, the magazine published an article describing the relationship between overeating, femininity, and race. The article, titled “Chapter on Female Features,” written by a woman named Leigh Hunt, reminded the reader that “the pleasure of even eating and drinking, to those who enjoy it with temperance, may be traced beyond the palate.” Hunt’s aim was to inform the reader that although eating to satiety and beyond could be enjoyable, greater rewards were to be reaped by keeping the appetite in check. Even better than gratifying the appetite, Hunt suggests, is to eat with moderation, so as to maintain one’s appearance. Women of the “utmost refinement,” Hunt intones, are far too frequently “wide of the mark.”

Punning her way through the piece, Hunt makes it clear that “excessive” eating leads to a figure that would be undesirable for cultivated white women. With more than a hint of sarcasm, Hunt acknowledges that “there are fashions in beauty as well as dress.” With this, she is suggesting that in other parts of the world, different standards of beauty apply. The place where fat women can be appreciated, it seems, is under the African sun, since in “some parts of Africa no lady can be charming under twenty-one stone,” or approximately three hundred pounds.

While Anglo-Saxon women were often the focus of dietary reform, Irish women commonly were derided as irredeemably greedy and fat. An article from 1848 titled “Sketches from Real Life” describes a “Mrs. Bridget Notable,” an Irish domestic. Mrs. Notable’s heft was indicative of both her race and her low-class standing. According to the author, her “stature is somewhat low, and…she slightly inclines to embonpoint.” Embonpoint is a French term for “plump” or “fleshy.” Mrs. Notable’s weight was, per the author, “just enough so as to give her form and face that firm and massive texture which appears as if it could resist the ‘wear and tear’ of almost any amount of labor.”

Another article makes clear the anxiety surrounding the mere possibility that a boorish, fat Irish woman might somehow make her way into polite white society. The 1855 piece “The Fat Widow” describes the fear of an interracial relationship between a decent Scotchman and an older Irish woman:

Someone mentioned that a young Scotchman, who had been lately in the neighborhood, was about to “marry an Irish widow, double his age and of considerable dimensions. “Going to marry her!” he exclaimed, bursting out laughing; “going to marry her! impossible! you mean, a part of her; he could not marry her all himself. It would be a case, not of bigamy, but trigamy; the neighborhood or the magistrates should interfere. There is enough of her to furnish wives for a whole parish. One man marry her!—it is monstrous. You might people a colony with her; or give an assembly with her; or perhaps take your morning’s walk round her, always provided there were frequent resting-places, and you were in rude health. I once was rash enough to try walking round her before breakfast, but only got halfway, and gave it up exhausted. Or you might read the Riot Act and disperse her; in short, you might do anything with her but marry her.”

In this and dozens of other articles in Godey’s, the fear of an Irish woman managing to filter into hallowed Anglo-American communities is palpable.

The new standard of beauty Hale seemed to hope for, that of the tall, slender, Anglo-Saxon Protestant woman, did arrive. It would come to be known in many New England circles as the “American Beauty.” Godey’s contributors would commonly describe this form of embodiment as such. This much was to be seen in an article titled “Le Melange: American Beauty,” in which the author claims,

There are two points in which it is seldom equaled, never excelled—the classic chasteness and delicacy of the features, and the smallness and exquisite symmetry of the extremities. In the latter respect, particularly, the American ladies are singularly fortunate.

The “American Beauty” ideal was nevertheless fraught and contested. For although the author of this article, a British man, praises American women for their smallness, delicacy, and symmetry of features, he nevertheless found them “most deficient in roundness of figure.” His assessment of “American” women’s delicacy and smallness as divine, and yet perhaps taken a bit too far, reveals just how conflicted he and many other men and women, especially those who were not American, were with the burgeoning slender aesthetic as an Anglo-Saxon Protestant American woman’s ideal.

And yet the power of the slender aesthetic as an American beauty ideal lay in its repetition. Godey’s was the earliest and most visible women’s magazine to glorify an ideal rooted in the multiple and colliding factors of Protestant asceticism, scientific racism, and the protoscience of health and beauty. In subsequent decades, however, it was to be one of many sources to promote the thin ideal.

Excerpted from Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia by Sabrina Strings with permission from NYU Press.