Would it not be hard upon a little girl, who is busy in dressing up a favorite doll, to pull it to pieces before her face in order to show her the bits of wood, the wool, and rags it is composed of? So it would be hard upon that great baby, the world, to take any of its idols to pieces and show that they are nothing but painted wood. Neither of them would thank you, but consider the offer as an insult. The little girl knows as well as you do that her doll is a cheat—but she shuts her eyes to it, for she finds her account in keeping up the deception. Her doll is her pretty little self. In its glazed eyes, its cherry cheeks, its flaxen locks, its finery, and its baby house, she has a fairy vision of her own future charms, her future triumphs, a thousand hearts led captive, and an establishment for life. Harmless illusion, that can create something out of nothing, can make that which is good for nothing in itself so fine in appearance, and clothe a shapeless piece of deal board with the attributes of a divinity! But the great world has been doing little else but playing at make-believe all its lifetime. For several thousand years its chief rage was to paint larger pieces of wood and smear them with gore and call them gods and offer victims to them—slaughtered hecatombs, the fat of goats and oxen, or human sacrifices—showing in this its love of show, of cruelty, and imposture. The more stupid, brutish, helpless, and contemptible they were, the more furious, bigoted, and implacable were their votaries in their behalf. The more absurd the fiction, the louder was the noise made to hide it—the more mischievous its tendency, the more did it excite all the frenzy of the passions. Superstition nursed with peculiar zeal her rickety, deformed, and preposterous offspring. She passed by the nobler races of animals even, to pay divine honors to the odious and unclean—she took toads and serpents, cats, rats, dogs, crocodiles, goats, and monkeys, and hugged them to her bosom and dandled them into deities, and set up altars to them, and drenched the earth with tears and blood in their defense—and those who did not believe in them were cursed and forbidden the use of bread, fire, and water. And to worship them was piety, and their images were held sacred, and their race became gods in perpetuity and by divine right. To touch them was sacrilege; to kill them, death, even in your defense. If they stung you, you must die; if they infested the land with their numbers and their pollutions, there was no remedy. The nuisance was intolerable, impassive, immortal. Fear, religious horror, disgust, hatred, heightened the flame of bigotry and intolerance. There was nothing so odious or contemptible but it found a sanctuary in the more odious and contemptible perversity of human nature. The barbarous gods of antiquity reigned in contempt of their worshippers!

This game was carried on through all the first ages of the world and is still kept up in many parts of it, and it is impossible to describe the wars, massacres, horrors, miseries, and crimes to which it gave color, sanctity, and sway. The idea of a God, beneficent and just, the invisible maker of all things, was abhorrent to their gross material notions. No, they must have gods of their own making that they could see and handle, that they knew to be nothing in themselves but senseless images—and these they daubed over with the gaudy emblems of their own pride and passions, and these they lauded to the skies, and grew fierce, obscene, frantic before them, as the representatives of their sordid ignorance and barbaric vices. Truth, good, were idle names to them, without a meaning. They must have a lie, a palpable, pernicious lie, to pamper their crude, unhallowed conceptions with and to exercise the untameable fierceness of their wills.

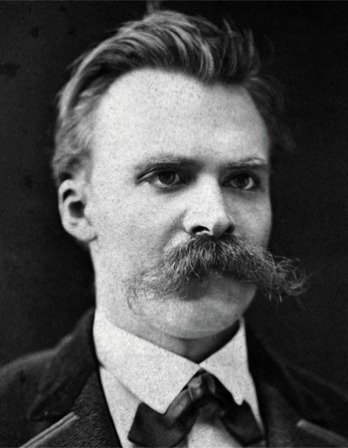

From “On the Spirit of Monarchy.” The son of a Unitarian preacher who supported the American Revolution, Hazlitt grew up in Ireland and the United States. Charles Lamb and William Wordsworth encouraged him to become a painter, but in 1805 he published his first book, On the Principles of Human Action. Over the next decade, Hazlitt established himself as a prominent essayist, writing on art, politics, and drama.

Back to Issue