[Richard Nixon and Nikita Khrushchev enter a kitchen display in the American National Exhibition.]

Nixon: I want to show you this kitchen. It is like those of our houses in California. [Nixon points to a dishwasher.]

Khrushchev: We have such things.

Nixon: This is our newest model. This is the kind which is built in thousands of units for direct installations in the houses. In America, we like to make life easier for women.

Khrushchev: Your capitalistic attitude toward women does not occur under communism.

Nixon: I think that this attitude toward women is universal. What we want to do is make life more easy for our housewives. This house can be bought for fourteen thousand dollars, and most American veterans from World War II can buy a home in the bracket of ten to fifteen thousand dollars. Let me give you an example that you can appreciate. Our steel workers, as you know, are now on strike. But any steel worker could buy this house. They earn three dollars an hour. This house costs about one hundred dollars a month to buy on a contract running twenty-five to thirty years.

Khrushchev: We have steel workers and peasants who can afford to spend fourteen thousand dollars for a house. Your American houses are built to last only twenty years so builders could sell new houses at the end. We build firmly. We build for our children and grandchildren.

Nixon: American houses last for more than twenty years, but even so, after twenty years many Americans want a new house or a new kitchen. Their kitchen is obsolete by that time. The American system is designed to take advantage of new inventions and new techniques.

Khrushchev: This theory does not hold water. Some things never get out of date—houses, for instance, and furniture; furnishings—perhaps—but not houses. I have read much about America and American houses, and I do not think that this exhibit and what you say is strictly accurate.

Nixon: Well, um…

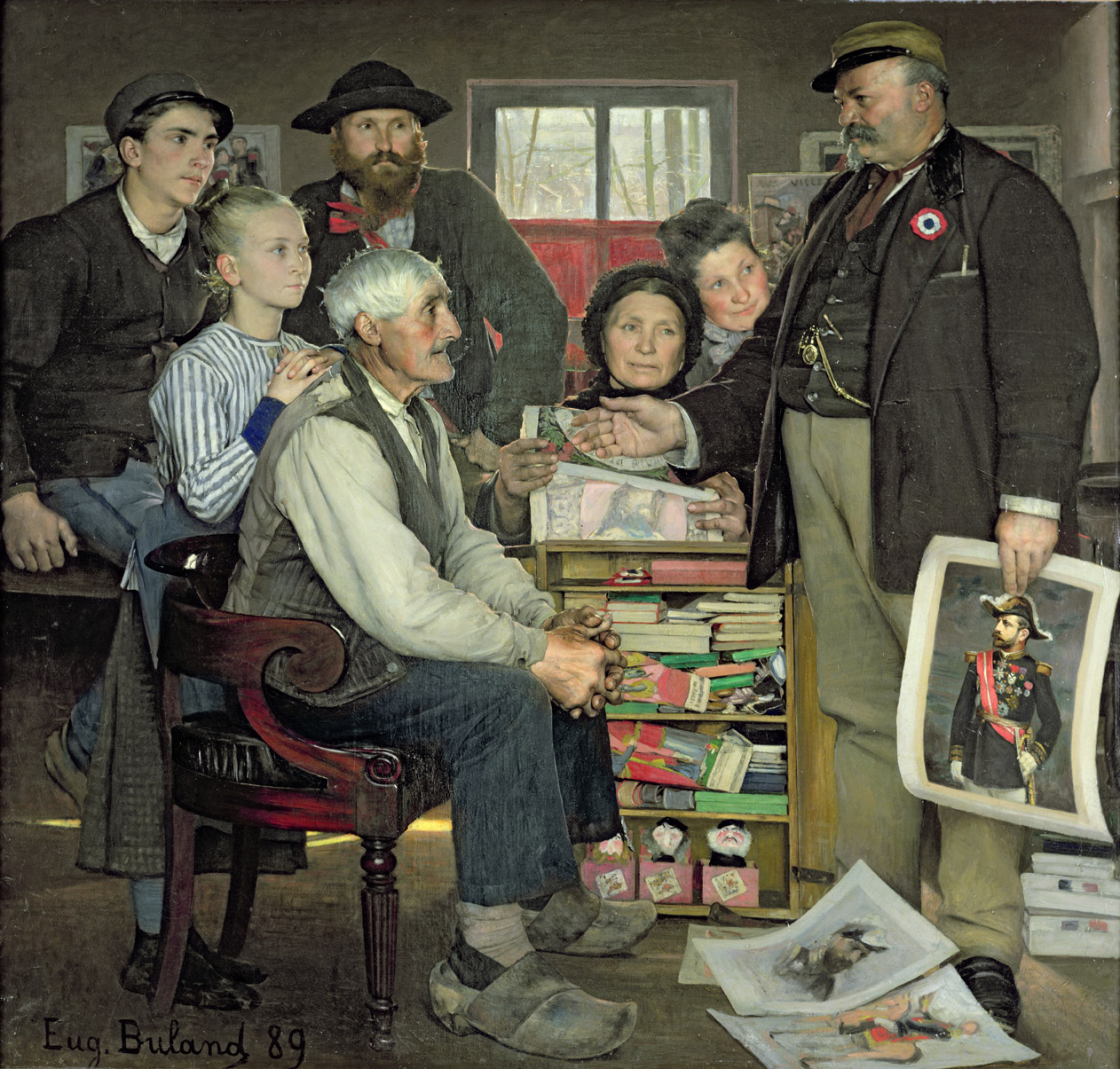

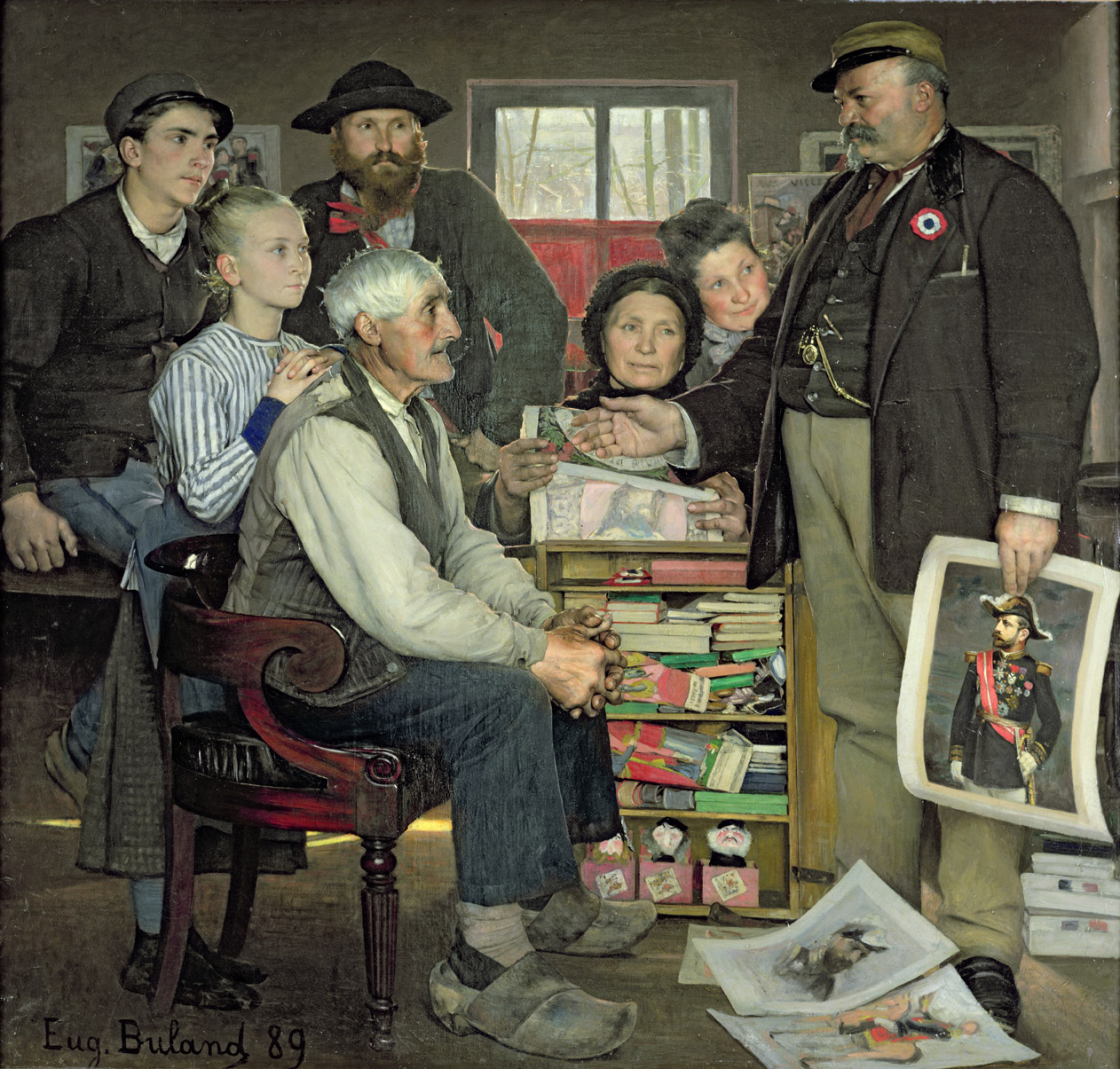

Propaganda, by Eugène Buland, 1889. Musee d'Orsay, Paris.

Khrushchev: I hope I have not insulted you.

Nixon: I have been insulted by experts. Everything we say is in good humor. Always speak frankly.

Khrushchev: The Americans have created their own image of the Soviet man. But he is not as you think. You think the Russian people will be dumbfounded to see these things, but the fact is that newly built Russian houses have all this equipment right now.

Nixon: Yes, but…

Khrushchev: In Russia, all you have to do to get a house is to be born in the Soviet Union. You are entitled to housing. In America, if you don’t have a dollar you have a right to choose between sleeping in a house or on the pavement. Yet you say we are the slave to communism.

Nixon: I appreciate that you are very articulate and energetic…

Khrushchev: Energetic is not the same thing as wise.

Nixon: If you were in the Senate, we would call you a filibusterer! You—[Khrushchev interrupts]—do all the talking and don’t let anyone else talk. This exhibit was not designed to astound but to interest. Diversity, the right to choose, the fact that we have one thousand builders building one thousand different houses, is the most important thing. We don’t have one decision made at the top by one government official. This is the difference.

Khrushchev: On politics, we will never agree with you. For instance, Mikoyan likes very peppery soup. I do not. But this does not mean that we do not get along.

Nixon: You can learn from us, and we can learn from you. There must be a free exchange. Let the people choose the kind of house, the kind of soup, the kind of ideas that they want.

[Both men enter the television recording studio.]

Khrushchev: [in jest] You look very angry, as if you want to fight me. Are you still angry?

Nixon: [in jest] That’s right!

Khrushchev: And Nixon was once a lawyer? Now, he’s nervous.

Nixon: Oh yes, [chuckling] he still is [a lawyer].

Lorenzo the Magnificent, detail from Procession of the Magi, by Benozzo Gozzoli, c. 1459. Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence.

Other Russian Speaker: Tell us, please, what are your general impressions of the exhibit?

Khrushchev: It’s clear to me that the construction workers didn’t manage to finish their work, and the exhibit still is not put in order. This is what America is capable of, and how long has she existed? Three hundred years? One hundred fifty years of independence and this is her level. We haven’t quite reached forty-two years, and in another seven years we’ll be at the level of America, and after that we’ll go further. As we pass you by, we’ll wave hi to you, and then if you want, we’ll stop and say, “Please come along behind us.” If you want to live under capitalism, go ahead, that’s your question, an internal matter; it doesn’t concern us. We can feel sorry for you, but really, you wouldn’t understand. We’ve already seen how you understand things.

Other U.S. Speaker: Mr. Vice President, from what you have seen of our exhibition, how do you think it’s going to impress the people of the Soviet Union?

Nixon: It’s a very effective exhibit, and it’s one that will cause a great deal of interest. I might say that this morning I, very early in the morning, went down to visit a market, where the farmers from various outskirts of the city bring in their items to sell. I can only say that there was a great deal of interest among these people, who were workers and farmers, etc. I would imagine that the exhibition from that standpoint would, therefore, be a considerable success. As far as Mr. Khrushchev’s comments just now, they are in the tradition we learned to expect from him of speaking extemporaneously and frankly whenever he has an opportunity. I can only say that if this competition which you have described so effectively, in which you plan to outstrip us, particularly in the production of consumer goods—if this competition is to do the best for both of our peoples, and for people everywhere, there must be a free exchange of ideas. There are some instances where you may be ahead of us—for example, in the development of the thrust of your rockets for the investigation of outer space. There may be some instances, for example, color television, where we’re ahead of you. But in order for both of us to benefit…

Khrushchev: [interrupting] No, in rockets we’ve passed you by, and in the technology…

Nixon: [continuing to talk] You see, you never concede anything.

Khrushchev: We always knew that Americans were smart people. Stupid people could not have risen to the economic level that they’ve reached. But as you know, “We don’t beat flies with our nostrils!” In forty-two years we’ve made progress.

Nixon: You must not be afraid of ideas.

Khrushchev: We’re saying it is you who must not be afraid of ideas. We’re not afraid of anything…

Nixon: Well, then, let’s have more exchange of them. We all agree on that, right?

Khrushchev: Good. [turns to translator] Now, what did I agree on?

Nixon: [interrupts] Now, let’s go look at our pictures.

Khrushchev: Yes, I agree. But first I want to clarify what I’m agreeing on. Don’t I have that right? I know that I’m dealing with a very good lawyer. Therefore, I want to be unwavering in my miner’s girth, so our miners will say, “He’s ours and he doesn’t give in!”

Nixon: No question about that.

Khrushchev: You’re a lawyer of capitalism, I’m a lawyer for communism. Let’s kiss.

Nixon: All that I can say, from the way you talk and the way you dominate the conversation, you would have made a good lawyer yourself. What I mean is this: here you can see the type of tape which will transmit this very conversation immediately, and this indicates the possibilities of increasing communication. And this increase in communication will teach us some things, and you some things, too. Because, after all, you don’t know everything.

Khrushchev: If I don’t know everything, then you know absolutely nothing about communism, except for fear! But now the dispute will be on an unequal basis. The apparatus is yours, and you speak English, while I speak Russian. Your words are taped and will be shown and heard. What I say to you about science won’t be translated, and so your people won’t hear it. These aren’t equal conditions.

Nixon: There isn’t a day that goes by in the United States when we can’t read everything that you say in the Soviet Union. And, I can assure you, never make a statement here that you don’t think we read in the United States.

Khrushchev: If that’s the way it is, I’m holding you to it. Give me your word…I want you, the vice president, to give me your word that my speech will also be taped in English. Will it be?

Nixon: Certainly it will be. And by the same token, everything that I say will be recorded and translated and will be carried all over the Soviet Union. That’s a fair bargain.

[Both men shake hands and walk offstage, still talking.]

From “The Kitchen Debate.” After a televised exchange between the vice president and premier, this conversation took place in the kitchen of a “typical American home” made for the Moscow exhibition. Elliot Erwitt, who took an iconic photograph of the event, claimed that the writer William Safire “got his job with Nixon as a consequence of my picture. He was doing PR for Macy’s kitchen at the time. Apparently he was instrumental in tracking down my photograph, which was used for a 1960 Nixon campaign poster (mercifully, Nixon lost).”

Back to Issue