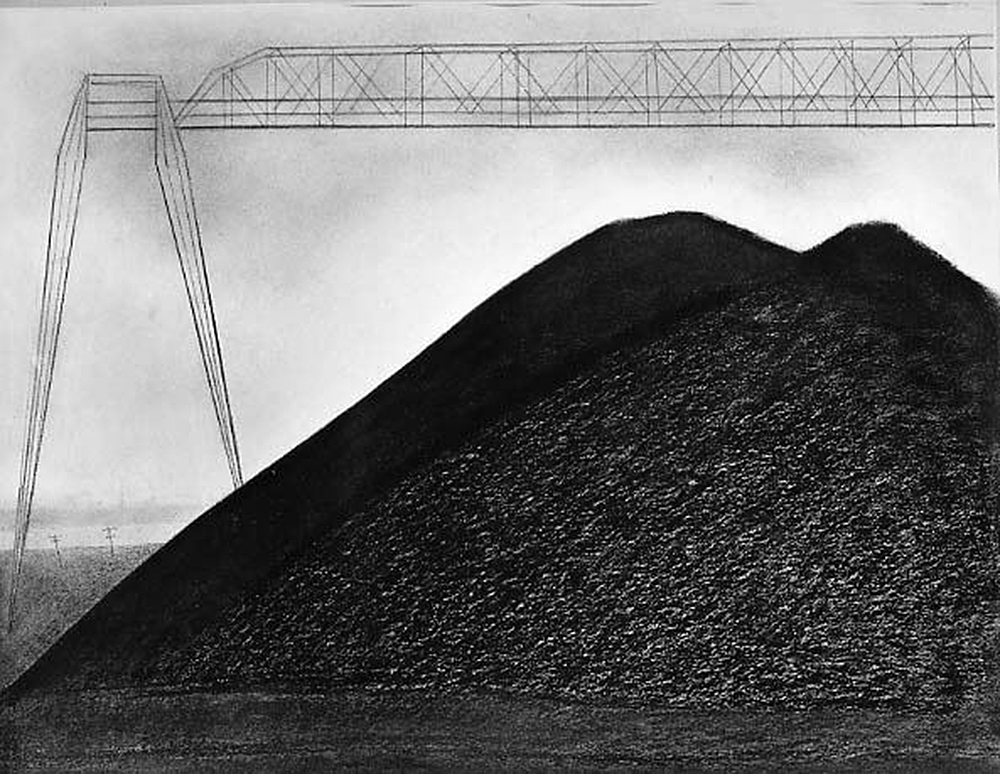

The Lonely Glen, by John Dillwyn Llewelyn, c. 1856. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005.

The titular villain of Gwyn Thomas’ 1946 novella “Oscar” is a man who owns a mountain. On top of the peak is a spoil tip, where all the refuse from the colliery carved into the mountain is dumped. Oscar owns that, too, along with many of the houses in the Welsh mining village below. In a way he also owns Lewis, a boy too young to find work in the coal pits whom Oscar pays to help haul his considerable body out of a local pub several nights a week instead. But he can’t stop Lewis from considering him, in the privacy of his mind, “a hog.” Oscar is a barn animal to many. As Lewis puts it,

Nobody liked him in the valley. The elements who went to chapel thought he was on a par with the god Pan, who was half a goat. The elements who did not go to chapel thought he was all Pan or all goat, or they were red revolutionary elements who thought that all such subjects as Oscar, who got fat out of stolen land, should have a layer of this land fixed over them in such a way as to stop their breathing.

The Dark Philosophers, of which “Oscar” is a part, was the first book Thomas ever published, but it already contained what would become the hallmarks of his distinctive voice: sprawling sentences, gallows humor, and an undercurrent of righteous political anger. You can find some combination of the three in all of his fourteen novels and short-story collections, several plays, and countless essays and newspaper columns. More than merely prolific, Thomas was once a writer of some international repute, and popular enough in Wales that in 1988 a statue of his head was stolen from Cardiff’s Sherman Theatre and never recovered. Yet even in his own country, that legacy has lately been in decline, however; Wales has no dearth of literary Thomases, and behind the poets Dylan and R.S., Gwyn is, in the words of Dai George, “by far the least known of this triumvirate.” This slow march toward obscurity strikes me as a loss not only because of the literary merits of Thomas’ work, which are many, but because they enshrine the lives, struggles, and radical movements of the Welsh working class.

Gwyn Thomas wrote about a world he knew well as the twelfth and last child of a coal-mining family in the Rhondda Valley of South Wales, a lush and mountainous region through which the River Rhondda cuts a meandering path. Born in 1913 to Walter Thomas and Ziphorah Davies, Gwyn quips in his memoir A Few Selected Exits that throughout his childhood, he and his siblings “were so deprived we lacked even the sense of being deprived. We were lucky that way.” His father was an autodidact deeply ambivalent about his work tending pit ponies; the money that he did not spend on books and clothing for himself he largely drank. To supplement his unreliable income, Ziphorah manufactured and sold the waterproof oilskins worn by miners out of a shed behind their terraced house. She died when Gwyn was only six—“overborne by child-bearing and the atmosphere of that shed,” he writes, with more than a trace of irony—and his sister Nana took charge of the Thomas brood.

The personal struggles of Gwyn’s family played out against a background of political and economic upheaval. By the time he was born, nearly 80 percent of the population of South Wales depended directly on mining for their livelihood, but the industry was already in decline. The region would soon be “crucified by mass unemployment and near-starvation,” historian Kenneth O. Morgan writes in Rebirth of a Nation: Wales 1880–1980. In the early twentieth century, coal workers also were becoming more militant, following the formation of the South Wales Miners’ Federation in 1898. An influential pamphlet called “The Miners’ Next Step” preceded Gwyn’s entrance into the Rhondda Valley by one year; written largely by active miners, it advocated for a seven-hour workday and higher minimum wage in addition to a program of “hostility to all capitalist parties.”

It was in this context that Gwyn’s earliest political convictions—and his sense of humor—were forged. Growing up, he writes in A Few Selected Exits, “the need for equality was accepted as being as urgent as the need for air, milk, speech. Anyone found truckling to authority or embracing the status quo was rejected as a freak.” This socialist, antiauthoritarian worldview was put to the test when Gwyn left for Oxford in 1931. He was able to enroll thanks to a combination of three state scholarships, occasional cash infusions from his working siblings, and, later, a grant from the Miners’ Welfare organization, for which his father’s occupation had made him eligible. (“He had been out of work so long it took serious research to make his connection with the industry clear,” Thomas jokes, “but they made it.”) At Oxford, he came into contact not only with young men from vastly different socioeconomic backgrounds than his own but also a number of genuine fascists who openly admired an emergent Hitler. In his memoir, he summed up the entire experience as “a series of spinning alienations”—not entirely surprising for someone who’d once written in a letter to his sister that “for a man to become a Bolshevik, he need be just the two following things: (a) sensitive, (b) exposed to the vileness of the private profit system.”

Thomas graduated without a first but with fifty pounds of savings he’d managed to squirrel away from the various awards he received “by bits of chicanery so minute they cannot be described.” The plan was to find a post teaching Spanish, his chosen subject, and failing that, to “allow [himself] a pound a week of pocket money, then…die of natural causes.” The teaching post proved impossible to come by for several years, along with any other kind of meaningful work, but rather than die he attempted instead to volunteer for the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. Though he was turned away because, as he put it, “the presence of an enfeebled eccentric…would do nothing but brace Franco,” he was tapped to help translate for the large groups of Spanish refugees arriving in Newport in 1937, during which time he “amazed his fellow workers by the energy with which he lectured the children on the principles of Marxism,” according to his biographer Michael Parnell.

Thomas soon found another outlet for his speechifying as an itinerant lecturer with the National Council of Social Services, and for the next four years he undertook “some of the most confusing bits of social work ever recorded.” Though he eventually secured a job teaching Spanish at a grammar school in West Wales, a post he held for twenty years, it was in this late interwar period of stagnation and malaise that Thomas’ early works are set. He completed his first manuscript in 1938, a novel titled Sorrow for Thy Sons, but he wouldn’t publish a book until The Dark Philosophers, a trio of novellas in which the central drama is put into motion by exploitative, low-paying work—or the lack of it. “Oscar” concludes with a furious Lewis leading his insensate boss to fall to his death; in “Simeon,” a boy takes a job with the prosperous owner of an oak planation and discovers that his employer has been sexually abusing his daughters for years. The title story concerns a once-radical reverend named Elijah who is convinced to take up the mantle of his former politics once more by a group of underemployed men, only for the fury to destroy his damaged heart and kill him.

The Dark Philosophers brought Thomas his “first taste of modest fame”: reviews appeared in leftist publications such as the Daily Worker, as expected, but the book was also praised by the Observer and, after Little, Brown and Company purchased the rights, by the New York Herald Tribune. And it earned him the admiration of the American novelist Howard Fast, who called The Dark Philosophers “a masterpiece…a testimony to the dignity and worth of all men.” The two men began a correspondence that lasted for several years, and Fast went on to distribute Thomas’ 1949 novel All Things Betray Thee, a fictionalization of the 1831 Merthyr Rising, through his pro-communist Liberty Book Club.

In defiance of Stendhal’s oft-quoted dictum that politics in the novel are akin to a gunshot in the middle of a concert, Thomas’ early work hews more closely to that of Grace Paley, who argued that even “the slightest story ought to contain the facts of money and blood”—that is, class, work, and family. In a letter, he put it more bluntly still, with a bit of fire-and-brimstone flair: “What I conceive to be the essential purpose of my existence on this earth [is] to stir up a wave of malevolent and unforgiving hatred against our lords and masters that will make them sorry they were ever born.”

This undersells the degree to which his writing was also absurd, funny, and occasionally slapstick—“Chekhov with chips,” as he once described it himself. Before Oscar meets a brutal end at the bottom of his own mountain, he passes out so thoroughly in the midst of an attempted seduction that Lewis cannot revive him: “I dropped his head back on to the table and even the sharp bang he got from that did not make him any wider awake.” The Alone to the Alone, which was published in 1948 and reprises characters from Sorrow for Thy Sons, is essentially a farcical Dangerous Liaisons targeting class traitors and lotharios Shadrich Sims and Rollo, the owner of a chain of grocery stores and a bus conductor too big for his fashionable golfing britches, respectively.

Thomas’ characters tend to speak the long, rambling, exaggeratedly literate sentences he did. In “The Dark Philosophers,” the character Walter observes to a young moderate he’s attempting to radicalize that “the need for beauty comes a long way after the need for food and warmth, and while people are still worried black and blue from the guts upward by that second need, they will see no need for beauty except perhaps that sort they get in thimblefuls from such articles as prayers, picture postcards, and young passion kindling among the mountain ferns.” Such dialogue led a reviewer for the Western Mail to note tersely that Thomas “must know the inhabitants of the Terraces would not converse like university dons.” But this choice was, for Thomas, not merely a matter of style but one of principle. In a 1950 interview he said, “The literary convention that insists poverty of pocket must be matched with poverty of speech has never made the slightest sense to me.”

It was also emblematic of the compulsive way that Thomas wrote, with a physicality that bordered on graphomania. He was notorious for filling and discarding notebooks and scrap paper, the care of which was left up to his housemates—first Nana, later his wife, Lynn. Several decades worth of them now are held at the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth. By his own admission, his writing was “decanted onto paper as fast as my sixpenny fountain pen could travel.” This energy frequently spilled over onto the printed page, and perhaps no more so than during the doomed reverend’s final sermon in “The Dark Philosophers”:

He spoke of the years he had lived, years of waste, loneliness, longing, stupid, stupid, hurtful, terrible, a ghastly, petty tragedy, the excreted, idiot filth of the violent fraudulent rich in their campaign to make a pounded cash-till of every human life not born with their stamp upon it, a brutal, damnable oppression to be destroyed if mankind were to live.

Despite the fact that these books earned him critical bona fides—the novelist James Hilton supposedly dubbed him “Marx with laughs”—it is characteristic of Thomas’ lifelong self-doubt that his memoir makes no mention of his early literary achievements except to disparage them briskly. (In 1938 he fled in a panic from a prospective meeting with the publisher Victor Gollancz before even crossing the threshold, though Gollancz would later go on to publish ten of his books.) He deadpans that the stories in The Dark Philosophers “contained a heavy ration of unnatural sex…existentialist slayings…and metallic cynicism honed to race-gang standard.”

This revisionism may also be due in part to the eventual softening of Thomas’ political convictions. By the time he wrote his first play in the early 1960s, he was no longer “in [any] mood for proffering messages”; his “first philosophy that had once chirped hope from every branch of its experience had shed its leaves and evicted its singing guest.” A friend to whom he showed the unfinished script called it sentimental and accused him of becoming “the graveyard of honest commitment in these disturbed times”—though conceding that the play might be profitable. In perhaps his most mainstream outing, Thomas made a number of appearances on the BBC’s Brains Trust, a show in which an anointed panel of experts fielded difficult write-in questions, such as “What is the basis of a happy marriage?” “Self-abnegation and good companionship,” one panelist replied.

Whether he could have recovered some of the righteous anger that once guided him during the National Union of Mineworkers’ strike of 1984–85—a bitter and violent dispute stemming from the announcement by the National Coal Board under Margaret Thatcher that it planned to close twenty coal pits at a loss of 20,000 jobs—is impossible to say: he died in 1981, at the age of sixty-eight. But part of The Dark Philosophers’ enduring power is that it contains within it a decisive rebuke of the very fatigue Thomas would later confess to:

We have seen many men turn tail and run away from what they used to say was the truth, that we have given up wondering why they should feel this urge to pay life the gross compliment of burning, to appease it, that very dignity without which life is as mean a dish as can ever be contrived.