Music is our myth of the inner life.

—Susanne K. Langer, 1942Jonathan Biss Says the Unsayable

The transfiguring language of music.

The first time I wondered what it might be like to die, I was thirteen years old. The occasion was not the death of a loved one, or a gruesome news story, or a Quentin Tarantino movie (each of which I had experienced previously), but rather my first encounter with Beethoven’s Sonata Opus 111.

I may have been just thirteen, but music had already been guiding and goading me—upsetting my applecart—for years; it stuck its pincers in me early and never let go. Growing up in a house with two professional violinists and one well-used record player, music was not just ever present, it was the vernacular. When I began playing the piano at six, it was more an inevitability than a choice: who doesn’t want to speak the language of the locals?

And what a language! From the beginning, it dazzled me. Music was poetic, intense, beguiling; English seemed frumpy in comparison. Before I even began playing, Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet and Verdi’s Rigoletto had commanded my attention and jump-started my imagination. Once I did start playing, little else mattered. Being able to access Beethoven’s world with my hands, feet, and heart, I felt uncharacteristically at ease in my own.

Op. 111 is the last of Beethoven’s thirty-two piano sonatas, his farewell to the genre in which he was most prolific, the genre he revolutionized and nearly ruined for future composers, having exhaustively and awesomely mined the form’s every crevice, its every expressive possibility. The word farewell is suggestive of many things—dignity, serenity, acceptance—none of which come close to conveying the content or character of this sonata. Op. 111’s first movement is all rage, and agony, and rage at being in agony. It begins in midsentence, the emotional storm already in progress, and for the entirety of the movement, it does battle. Its main theme, in brutal, fortissimo unison, comes to a screeching halt three notes in, forcing the listener to fixate on the gnashing ugliness of the interval created by the previous two. This mood never abates; the movement is at nearly all times severe and airless, and by the end of it, we are as exhausted and shaken as Beethoven himself. Even the coda’s sudden move into major brings no relief. It is anchored by three upward intervals, each larger than the one before, the last a yawning chasm, an expression of a want that will never be met.

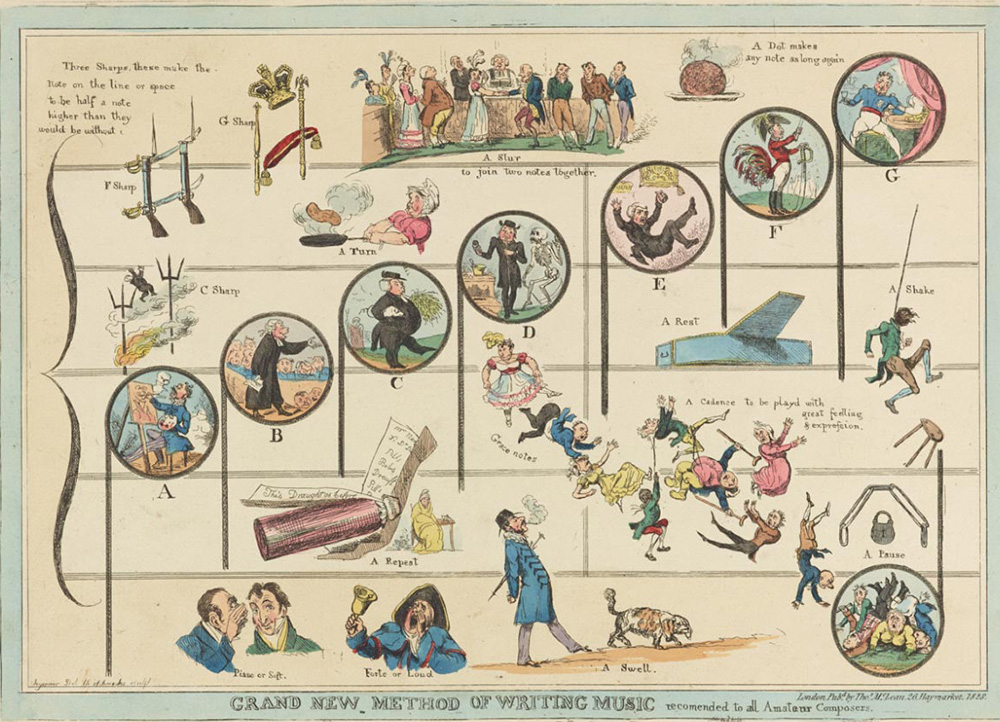

Grand New Method of Writing Music Recommended to All Amateur Composers, by Robert Seymour, 1828. © Philadelphia Museum of Art, William H. Helfand Collection, 2012.

I remember so precisely my inability to breathe when, at thirteen, I first heard this movement come to its terrible end. I hadn’t realized that bitterness was a part of music’s expressive arsenal; for a sweaty, bespectacled teenager, who lived and felt through music, this was an unsettling discovery. The silence in the concert hall seemed thick and miserable, so unlike the silence that had preceded the start of the movement not ten minutes earlier.

When the silence was broken, the particles in the room, and in my body, again reorganized themselves. “I know not how such things can be!— / I breathed my soul back into me.” I very much doubt that Edna St. Vincent Millay had the theme of the second movement of op. 111, much less its effect on thirteen-year-old me, in mind when she wrote those lines. And yet, as an evocation of what this music is—of what it does—they are as precise as they are eloquent. I could not, and cannot, do better.

Because I really, truly, do not know how such things can be. I do not understand, in spite of thirty years of playing the piano, and thirty-six years of hearing C-major chords, how the C major that opens the second movement—the same C major that brought the first movement to its remorseless close—can be so instantly transfigured. I do not understand, after thirty-six years of attempting to regulate my own emotions, with varying degrees of success, how Beethoven can so effortlessly divest himself of the rigor and anguish that seemed all-consuming just moments ago.

All I do know is that they are gone. That with the first notes of the second movement, every last tooth has been ungritted, every last muscle unclenched: this is pure wonderment. The rhythmic austerity of the first movement has been replaced by the gentlest of sways, the raging dissonances by uncluttered, open consonance, the furrowed brow by the widest of eyes.

Beethoven loved nothing more than a monumental conclusion. The last time Beethoven had ended a piano sonata in C major—the Waldstein—he did so with no fewer than twenty-nine hammered-out C-major chords. When the trajectory of the work is darkness to light—think of the Fifth Symphony—this tendency is often taken to an almost ridiculous extreme.

A freewheeling traversal of the keyboard led back to the plainsong of the opening. I heard the music bloom one last time, and then, inevitably, sigh into a final cadence. I heard one faint C-major heartbeat, then a second, then a third. I waited for a fourth.

It never came.

That third C-major chord, without fanfare or elongation or any superimposed sense of finality, was the last. It ended just as the first two had, and when it did, the piece was no more. It did not conclude; it entered into the void. I didn’t dare move, but I drew in my breath sharply.

I had heard a death.

Beethoven wrote this death in 1822; his own came five years later. He may have said farewell to the piano sonata with op. 111, but he went on to write two sets of bagatelles—epigrammatic delights, both of them—and the gargantuan, cryptic Diabelli Variations. He wrote the Ninth Symphony and the Missa Solemnis. He wrote five string quartets, one more staggering than the next. He endured numbing loneliness, alcoholism, deafness, family drama, and diarrhea. He lived a fairly wretched life, but he managed to work doggedly and produce a steady stream of staggeringly great music. Op. 111 died, but Beethoven lived.

This is what makes writing about music such a tricky business. Great literature can be rich in subtext, of course, but its text has meaning, too. A bed might be a metaphor for a coffin, but it is first and foremost a bed. Novels and poems make use of all those same words we use every day, to tell people that we love them or hate them or want them to bring us a pineapple.

Music is not like this; it is all subtext. Music’s mysterious capacity for saying the unsayable comes, in part, from its inability to say the sayable. For those of us who love it beyond reason, music speaks to our unconscious desires and fears, gives voice to the feelings we don’t know how to express, and sometimes don’t even know we have. But it has never suggested to anyone that they deliver fruit.

Ella, by Max Ferguson, 1989. © Private Collection / Bridgeman Images.

In other words, music is exquisitely personal, and constantly, maddeningly subjective. If you love it—as anyone who embarks on this folly of trying to write about it must—you want to say something about it that is sharp and true, which makes it all the more dispiriting to find that someone else’s truth might be so different. When I write about the “gnashing ugliness” of the main theme of op. 111’s first movement, that is deeply subjective; objectively, it is merely C–E flat–B natural.

When I say that I lived, and live, through music, that is what I mean. I am frustratingly inscrutable to myself—so rarely do I properly understand why I feel the way I feel. And even when I do have the words to describe my emotions, I’m usually highly reluctant to use them. Music is my interpreter, my megaphone, my teacher, my consoler-in-chief. To me, it is magic.

It is also, I fear, a dangerous crutch. Am I a musician because music speaks to, and for, me in this way? Or does music speak to me so powerfully because I need it to, because I, who am generally so difficult to shut up, am still rendered as inarticulate as that thirteen-year-old with night terrors when it comes to communicating my own emotions? Why is it that for some of us, music is almost painfully suffused with meaning, whereas for others it is just C–E flat–B natural? Are the people who react most strongly to music those of us who are least able to say the things we need to say?

Whatever op. 111 meant to Beethoven, its impact on me has been nothing less than transformational. And the same goes for the late works of Mozart, of Schumann, of Britten, and on and on and on. It is not merely that I find them beautiful or mesmeric or nourishing; it is that I sense that they are accessing something that I want badly to access myself.

And what is that something? I am characteristically and distressingly hazy on the point. The music itself is either bringing me closer to the answer or insulating me from it.

From Coda. Copyright © 2017 by Jonathan Biss. Used with permission of Jonathan Biss and Amazon.

Jonathan Biss

From Coda. Raised in Bloomington, Indiana, Biss, a concert pianist, claims to have made his Carnegie Hall debut several months before his birth, in 1980, when his mother, Miriam Fried, a renowned violinist, performed a Mozart concerto there while pregnant. In 2016 Biss began a study of composers’ “late style,” performing and writing on the late-in-life works of Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Britten, Schubert, Schumann, and others. He lives in New York City.