There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact.

—Arthur Conan Doyle, 1891Organized Antilabor

The inner workings of Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency.

The motto of Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency is, “We Never Sleep,” and the secret operative is the apple of that ever-wakeful eye, for it is the secret operative who is the main source of revenue and profit at every branch of the agency.

No talent or skill whatever is necessary in order to become an operative of this class, and a workingman of average intelligence, who is willing to obey orders, is the one who, as an operative, gives the agency the best satisfaction.

The reports of the secret operative as to the competency and industry of his fellow workmen are of interest and importance to the client, as this information, which he would find it difficult to obtain otherwise, enables him to weed out such of his employees as are either incompetent or inclined to shirk.

It is the dominating policy of Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency and, consequently, the chief aim of the secret operative to prevent, if possible, the formation of a union at the plant of the client, or, if he finds a union already flourishing, to keep it in check and to do everything in his power to disrupt it.

It is a simple matter to prevent the formation of a union; but to destroy one after it has gained a foothold is a hard and complicated proposition. Yet the agency’s phenomenal growth in fame and power since 1892, and more particularly within the last three years, is almost entirely due to the successful accomplishment of this kind of work, and it is their boast that they have no rival or competitor who can parallel their achievements in this field.

Infinite care is exercised at all times by the officials of the agency to preserve the incognito of the secret operative, first, because of the possible danger attendant upon discovery and, second, because the operative is thereafter a marked man, and his usefulness to the agency is ended.

Within a few days after his employment, the secret operative is given a number by the superintendent and told to use that number as a substitute for his regular signature on all reports, letters, and expense bills.

The superintendent of the office and his assistant superintendents are the only ones aware of the operative’s name. To the clerical department that handles his accounts and typewrites his reports, and even to the client who pays for his services, the operative is known merely as a certain number.

As a further precaution, each branch of the agency keeps a number of post office boxes rented under assumed names, and when the secret operative is ready to leave for his field of action, he is given the number of one of these secret agency boxes and told to address all reports to fictitious persons in care of this box.

The operative on arriving at his destination rents a post office box under his own name and promptly sends the number to the agency. The superintendent or assistant superintendent in charge of the operative sends instructions, salary, and expense money to this box, using plain stationery and envelopes. All letters of instruction to secret operatives are written with lead pencil, but the envelope may be addressed with pen. It is a strict rule of the agency that neither the one nor the other may be typewritten, for fear it might attract attention.

The operative is also required to have a room exclusively for himself, which makes it possible for him to write his reports and letters in strict privacy.

After the operative has secured a room and safely opened communications with the agency, he at once applies for work at the client’s plant, as a bona fide craftsman, and does his best to secure work through his own efforts. However, if after a reasonable length of time he is unable to get employment, the agency makes a virtue of necessity and confidentially discloses the operative’s identity to the client. He is put to work without further delay.

The operative works as hard and as steadily as anyone else about the plant, and oftentimes harder, so as to set a good example. If he notices any of his comrades killing time or violating any of the firm’s rules, he is sure to mention the names of the offenders in his report that same evening; or if he discovers an incompetent employee, he is likewise sure to mention the fact. It is also the duty of the operative to suggest changes or improvements in the plant that might benefit the client.

After the operative is through with his work for the day, he must make it his business to meet his fellow employees, talk with them, “treat them to the drinks,” and cultivate their friendship. By being around with the men evenings, he soon learns their attitude toward the client, and whether they are contented with conditions. If no union exists but there are strong advocates of one, the operative reports the names of these men as “Dangerous Union Agitators,” and within a few days they are discharged on some pretext.

However, if the operative finds that a union is in existence, and that many of the client’s employees belong to it, his instructions are to assume the role of an ardent union man, join the union, and report to the client the nature of the proceedings of every meeting, and the names of all members. The client then begins to discharge his union employees on different excuses, and fills their places with nonunion men. It frequently happens that the union notices the discrimination practiced and orders a strike as a last resort to save the organization.

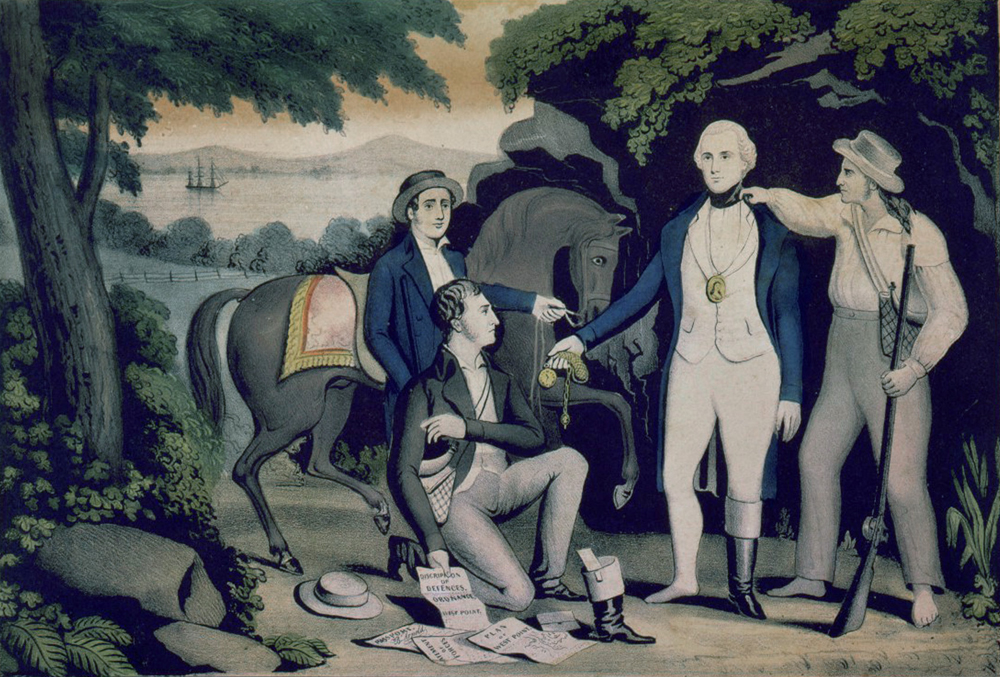

Capture of André 1780, lithograph by Currier & Ives, c. 1845. © The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

During the progress of the strike, the services of the secret operative are more valuable than ever, for he keeps the client posted as to the strength, doings, and intentions of the strikers, and this information, in nine cases out of ten, decides the victory in favor of the client, and forces the men to sue for peace on any terms.

After things quiet down and conditions again become normal, it is but good business policy for the client to retain the secret operative in his employ indefinitely, as he considers him a necessary tool in the conduct of his business.

The Pinkerton Agency never advertises for nor hires real detectives, for the simple reason, astonishing as it may seem, that it is never in need of such persons; and if the best detective of London, Paris, or New York were to apply for a position at any office of the agency he would be informed there was really no opening at the present time. A polite, meaningless promise might be handed out.

Whenever a criminal case comes up, it is turned over to a general operative, or if no general operative is at liberty, the superintendent or one of his assistants handles it. This arrangement therefore obviates the necessity of employing tried and experienced detectives.

Though the agency’s system of hiring new operatives insures secrecy, yet it is very simple. Let us assume that an office is in need of a new general operative. As this class of operatives is principally recruited from the ranks of salesmen, the office in question will insert an advertisement similar to the following, in every newspaper in the city:

WANTED—A bright, experienced salesman to handle good line; salary and commission. Excellent opportunity for right man to connect with first-class house. State age, experience, and references.

This ad is allowed to run several days, after which one of the clerks makes a round of the newspaper offices, collects all the answers, and turns them over to the superintendent. This official carefully examines each application, noting particularly the age, experience, and language of every applicant. He then grades the papers on their merits as skillfully and conscientiously as any professor, after which he commissions one of his assistants to interview the applicants, and if he discovers among them one whom he thinks intelligent enough to make a competent general operative, to sound him as to his willingness to enter the service of the agency.

As there are many salesmen who are overworked, underpaid, and on the lookout for a change, the assistant superintendent’s only task is to single out that applicant whose appearance and intelligence impress him most favorably; and if his selection develops into a good general operative, it is a matter of congratulation to the office.

However, to begin with, the new employee is ranked as a special operative, and it is only after he has been tried and given satisfaction on a number of operations ranging from ordinary shadow work to the most complicated investigation that he is styled a general operative and placed in line for promotion to the executive department.

The secret operative is hired in the same manner as the general operative, excepting that the form of the advertisement varies so as to accord with the nature of the work. Thus if a secret operative is wanted who is a practical coal miner, the ad is changed to read as follows:

WANTED—At once several competent and experienced coal miners. Top wages and steady employment to good, able men. State age and experience.

The ad, calling for several miners instead of one, appears quite natural, and precludes the barest possibility of arousing suspicion in the most watchful quarter.

The assistant superintendent detailed to “sound” a prospective secret operative, until morally certain of his man, exercises the utmost discretion. At the best it is a difficult mission to propose perjury and treason to a man, yet this is exactly the nature of the proposition that the Pinkerton representative offers the coal miner, the mechanic, or any other prospective secret operative, for he asks him in carefully chosen, honeyed words to swear allegiance to an industrial union of his trade, and to violate his oath by betraying the union’s secrets and doing his best to destroy it.

It often happens that four out of five men interviewed reject the agency’s offer, and the fifth who is willing to accept is either illiterate or otherwise undesirable, so that it takes days, and sometimes weeks, before the agency succeeds in getting a man.

Once suspicion is aroused, everything feeds it.

—Amelia Edith Barr, 1885Contrary to popular belief, the agency does not pay high salaries to any class of operatives. The special and general operative gets a salary rarely if ever exceeding fifteen dollars a week when working in the city where the office is located; and when detailed on work outside the city, he is allowed, besides, his living and traveling expenses.

The secret operative necessarily receives a better salary, as he can earn more than fifteen dollars a week by simply working at his trade.

The agency therefore pays him the sum of eighteen dollars a week, and in addition compels the client to pay all his living and incidental expenses. In this way the secret operative can, if he is economical, save his entire salary. But all of the money that the operative earns as a result of his work at the client’s plant is credited to the account of the client, the operative not being permitted to keep any of it for himself.

In short, the secret operative sells his honor and the interests of his brothers for eighteen dollars a week, net.

About This Text

Morris Friedman, from The Pinkerton Labor Spy. Born in Russia in 1883, Friedman worked until 1905 in Denver as private stenographer for James McParland, one of the best-known operatives of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. Shortly after publishing this exposé of labor spies, Friedman was a star witness for defense attorney Clarence Darrow at the 1907 trial of union leader William Haywood, who was charged with and acquitted of murdering former Idaho governor Frank Steunenberg.