Mademoiselle V…in the Costume of an Espada, by Edouard Manet, 1862. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, H.O. Havemeyer Collection, bequest of Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929.

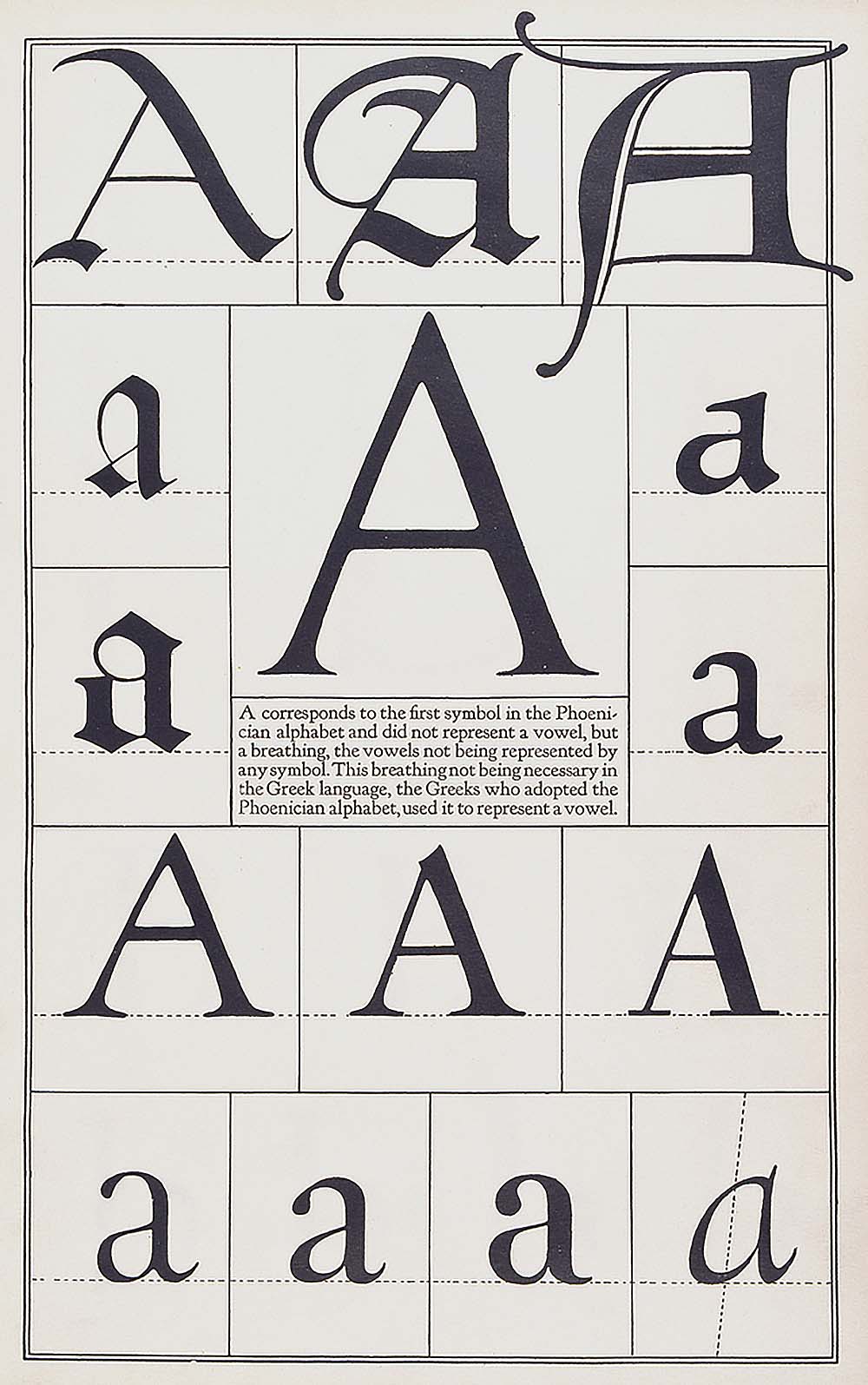

As academic Arthur Riss puts it so well, “It is a truth now universally known that the scarlet letter upon Hester Prynne’s chest designates much more than adultery.” For another scholar, Laura Doyle, “Hester’s ‘A’ is a layered code,” one that gestures toward the concealed violence of American imperialism. And, in Franny Nudelman’s words, “Whether considered from a formal or a cultural vantage point, the letter’s power lies in its referential latitude, which allows it to accumulate and sustain a variety of readings under the rubric of its own simplicity. Its indeterminacy is indistinguishable from its inclusiveness, and both determine its critical stature.” Building on such formulations of the letter’s indeterminacy and layers of meaning, I propose another designation for the letter A, one that reflects or contains the following index from an 1846 issue of the National Police Gazette:

Abortion, prevention of

Abortion, seduction, and murder

Abortion, a felony

Abortionist, Restell the

Abortionist, convicted

Abortionists, detection of

Abortionists, horrible deeds of

Abortionists, more work of the

Abortionists, of New York

Abortionists, still at work

While I cannot prove that Nathaniel Hawthorne happened on precisely this page, it encapsulates a cultural phenomenon of which he must been aware. The letter folds the secret of a declined alternative within it, complicating the view that sex, pregnancy, and childbirth follow one from the other in an escapable train of consequences for Hawthorne’s protagonist.

The practice of abortion and its facilitation of nonreproductive sex in New England cities propelled medical and legal debates regarding pregnancy and its regulation in Hawthorne’s time, all of which played out in the press, in advertisements for abortifacients, in medical journals, and in the publicized trials of famed abortionist Madame Restell, the figure above named by the National Police Gazette.

By the time of The Scarlet Letter’s publication, the practice of abortion had expanded into a thriving business, generated by advertising and transforming into a lucrative area of medical specialization. As historian Janet Farrell Brodie explains in her preface to Contraception and Abortion in Nineteenth-Century America, “What began in the 1830s as the focus of a small group of social and health reformers—Robert Dale Owen and Charles Knowlton especially—by the 1860s was the province of a diverse assortment of entrepreneurs and businesspeople.” And, reflecting on the drop in the white birth rate of the time, Brodie demonstrates that the demand for abortion and contraception produced the supply, which in turn produced more demand: by virtue of this back-and-forth process, white marital fertility declined in the antebellum period, a pattern that continued through the century. According to historian James Mohr in Abortion in America, “One indication that abortion rates probably jumped in the United States during the 1840s…was the increased visibility of the practice. It is not unreasonable to assume that abortion was more visible at least in part because it had become more frequent. And as it became more visible, more and more women would be reminded that it existed as a possible course of action to be considered.” For Mohr, a “dramatic surge of abortion” took place after the 1830s, attributable to its commercialization and to the desire of women (primarily married white Protestant women) to delay or prevent childbearing. In light of this context, the story of Pearl’s birth is interlineated not only with illegitimacy but also with contingency.

As the National Police Gazette indicates, attempts to put the practice of abortion outside of women’s reach repeatedly failed. With the abortionists “still at work” despite the law, their influence and services proliferated as the kind of open secret to which Hawthorne was drawn. Women knew how to procure what they needed and how to read the abortionists’ advertisements, even as those advertisements became increasingly oblique. Indistinct references to menstrual-cycle obstructions, for example, brilliantly evaded censure while delivering the necessary information for obtaining cures.

At the same time, those who opposed the practice introduced more strident terms, shifting any ambiguity surrounding pregnancy and abortion into definitional clarity. In 1844 the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal carried this announcement about abortionists: “The law has not reached them…Their trade in infanticide is unquestionably considered, by these thrifty dealers in blood, a profitable undertaking.” Equating abortion and infanticide, the journal’s editorialist here followed the lead of physician Theodric Beck, whose multiply reprinted Elements of Medical Jurisprudence placed abortion as a subsection of his chapter on infanticide and outlined the methods by which both crimes could be detected.

As conservative medical men thus moved birth into their purview and systems of classification, they worked to illuminate the world of women’s primary methods of reproductive control, first-trimester abortifacients or surgical terminations, and to redefine the meaning pregnancy itself. That is, they worked to cast the early, ambiguous months of a pregnancy (in which a woman may or may not have been experiencing an obstructed menstrual period) in terms of the last months (in which a fetus clearly presented itself) and to define the entire sequence of gestation as life unfolding. Moving life’s origins to conception meant closing what had earlier remained open to interpretation, namely the possibility that nothing as much as everything was happening deep within a woman’s uterus. “Society first demanded the crime,” Madame Restell announced in 1847. “And by what right does it interfere with the concerns of one who was never born, and therefore never was, and possibly might never have been, a member of society?” From her point of view, she argued, preventing the suicide of an abandoned or disgraced woman put her on the side of life, of the living.

According to historian Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz in Rereading Sex, practices associated with reproductive control were traditionally communicated through the “secret knowledge of women’s vernacular culture,” which included the “various means of preventing and terminating pregnancy.” With early nineteenth-century migrations of large numbers of women away from traditional communities to urban centers such as New York and Boston, the transmission of this community knowledge was interrupted, creating “the grounds for the dissemination of printed information on abortion and the rise of female abortionists” who freely advertised their services in a public arena. Whereas vernacular birth-control practices—passed on like the dark tales to which Pearl refers when she overhears “the old dame in the chimney-corner”—had been disapproved of in a religious context but tolerated under common law, the legibility of this knowledge in the print culture of mid-nineteenth century America provoked a reaction that would lead abortion to be declared, by the 1860s, “the great crime of the nineteenth century,” as nineteenth-century doctor Edwin M. Hale dubbed it in the title of his third book on the subject.

Hawthorne was writing at a time when something fairly obscure was coming to light in new ways, accompanied moreover by the consolidation of male medical authority and jurisprudence. Physicians promoted themselves as trained observers who, as James Mohr demonstrates, shifted the status of the early-stage fetus from “potential for life” to life itself. In early nineteenth-century America, abortion was neither rare nor considered morally or legally wrong, as long as the drugs and procedures were administered prior to the quickening, the sensation of fetal movement around the end of the fourth month of pregnancy. However, once these same remedies became more publicly legible in the booming print culture of the 1840s, an intensified discussion surrounding the meaning of fetal life quickly followed. For Mohr, the medical and legal surveillance of women’s pregnancy went hand in hand with the professionalization of medicine over the same period, propelled by both existential and financial exigencies. Regular physicians, those with university training, did not want to compete with the “irregulars” dispensing vernacular remedies in the lucrative market surrounding women’s reproductive health. The regulars promoted themselves as the protectors of women against quacks peddling poisonous compounds. They also allied themselves with legislators, legitimizing their work as a form of national advancement and calling attention to the declining white birth rate.

In addition to the regulars, the most established phrenologists of the antebellum era, Lorenzo and Orson Fowler, positioned themselves in favor of strict antiabortion legislation. In their best-selling, multiply printed books on marriage, parenting, and human health, they promoted a theory of social reform derived at once from phrenological principles and patriarchal authority. Taking a strong stand against abortion, they published the works of like-minded writers, such as Hester Pendelton, whose book on parenting argued that abortion licensed adultery because it provided women with the means of erasing the evidence of their misbehavior. Addressing the subject in his popular 1846 polemic, Maternity; or, the Bearing and Nursing of Children, Orson Fowler communicated the extent to which he believed abortion prevailed in New England, and not just among poor, desperate women:

Many…women, who stand in high public estimation, have perpetuated this heinous crime, in order to hide their shame. The practice of procuring abortion, or, to use a less offensive expression, inducing a miscarriage, has of late become so common that it requires to be placed before the public in all its naked atrocity. From the increasing number of unprincipled persons who publicly advertise this destructive practice, it is evident that it is extending to a fearful degree in this country.

Before 1821 no state in the country had a statutory law against abortion. By 1850, when such arguments had become common currency, seventeen states had criminalized abortion. In 1844 Massachusetts also clarified its position on concealed pregnancies, its legislative report containing the following directive: “Whatever woman conceals the death of any issue of her body, which, if born alive, would have been a bastard, so that it may not be known, whether such issue was born alive or not, or whether it was not murdered, shall be punished.” The laws and the medical or pseudomedical declarations shared the same ambition of producing clarity over concealment or uncertainty. They aimed not only to separate legal from illegal, alive from dead, true from false, but also to define borderline areas of activity and secrecy as threatening on a wide social scale.

Such definitional heavy-handedness is altogether thrown out by The Scarlet Letter, and the novel retains what scholar David Greven calls a literary “empathy with women’s experiences.” It does so by skirting the kind of nailed-down definitions demanded by law and medicine, extending ambiguity as concomitant with the creative freedom to choose: how something is read, what shadows to hide in, what ways forward and backward one might take. Hawthorne can then redefine Hester’s adulterous sex with the minister as having “a consecration of its own,” shifting the experience into her frame of reference and away from the one that torments Dimmesdale to death. He similarly refutes life’s ostensibly inherent value when he has Hester decide that it is “not worth accepting,” not for women in the world as she sees it, nor “even to the happiest among them.” This decree ushers in her conclusion that “society is to be torn down,” as well as her conclusion that not being born at all is, in some cases, preferable to being born.

In the early 1800s the theological position that life originated with conception resurfaced in popular medical tracts opposing abortion. Soul, life, and embryo entwined in discussions of human origins and human physiological development. Theodric Beck, for instance, asserted that “to extinguish the first spark of life” was a crime “both against our Maker and society…these regular and successive stages of existence being the ordinances of God.” In physician Thomas Radford’s words, “The value to society of the embryo is as great as the fetus in utero, in every way, except as to degree of development.” On the other side of the debate, materialist explanations illuminated fetal development and human life apart from abstract values and theological concepts; they conceptualized living entities as material entities, composed of particles like the rest of the known universe, both animate and inanimate. While the pro-life side, to import a useful anachronism here, argued that abortion denied a child “the right of birth” (as the 1844 edition of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal noted), the pro-choice side asked after more precise meanings of the word itself.

For instance, the renowned reproductive-rights proponent Charles Knowlton went right to the heart of the issue in his 1825 book on the material organization of the universe, stating, “I shall say that the word life, like the word soul, is a name without a thing.” In his Fruits of Philosophy, or the Private Companion of Young Married People, published in 1832, Knowlton maintained that the fetus possessed “no more rights than any one of [a woman’s] extremities,” and that pregnant women required society’s sympathy and concern. Holding apart the idea of a fetus from what he considered its actuality (a vegetable state transforming into a “low degree of animal life”), he insisted that “what it is while it is a fetus” must not be associated “with an idea of what it will be.” Partway through his study, moreover, Knowlton visualized this scenario: “I leave the reader to imagine the misery of the unfortunate female, as alone she weeps, who knows that few months must develop that which will degrade her in the eyes of her community; I say nothing of her paramour, who may be a generous but warmhearted young man.” For Knowlton, pregnancy was a private matter. Terminating it did not “strike at the peace, the security, and existence of society,” as Massachusetts attorney general James Austin claimed it did in 1838.

Even if Hawthorne never read Knowlton—though Fruits was a best seller in its time—tracing The Scarlet Letter to the fervent antebellum conversation about pregnancy widens its sources and places its feminist politics in a new light. Consider the following excerpt from A.M. Mauriceau’s 1847 Married Woman’s Private Medical Companion: “What epithet then belongs to him who makes it a trade to win a woman’s gentle affections, [and] then abandons her?…Why is it that the man goes free and enters society again…while the woman is a mark for the finger of reproach, and a butt for the tongue of scandal? Because she bears about her the mark of what is called her disgrace. She becomes a mother; and society has something tangible against which to direct its anathemas.”

Adapted from Certain Concealments: Poe, Hawthorne, and Early Nineteenth-Century Abortion by Dana Medoro, published by the University of Massachusetts Press. Copyright © 2022 by University of Massachusetts Press.