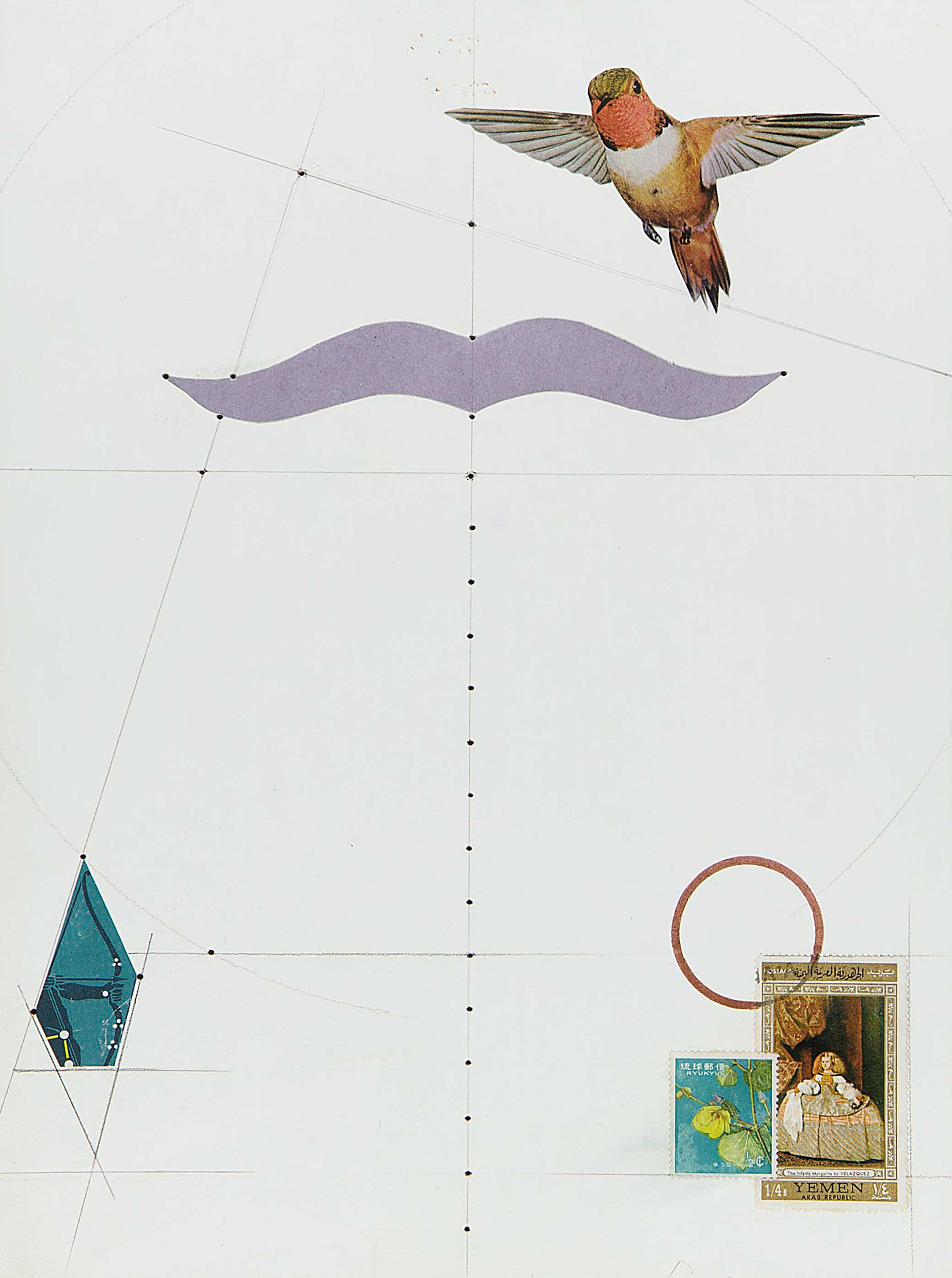

Untitled (cutout of bird in flight), by Joseph Cornell, 1970. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of the Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation, 1991.

In my debut novel, Mother Ocean Father Nation, a brother and sister must navigate their lives in the wake of a mid-1980s military coup in an unnamed and fictionalized South Pacific island nation. The island is an amalgamation of places that I had become familiar with through my dissertation research on Indian indentured servitude in the British Empire, including Fiji, Trinidad, Guyana, Uganda, Kenya, and South Africa. As the country in the novel falls into disarray, a figure known only as the General seizes control of the government, ostensibly to restore order and calm.

The General was inspired by a number of late twentieth-century dictators with roots in the military: Fiji’s Sitiveni Rabuka, Chile’s Augusto Pinochet, and Uganda’s Idi Amin. Researching Amin’s rule in Uganda—particularly his expulsion of the country’s Indian population—led me to a curious story. Whereas many refugees and migrants leave their home country for one where they have some sort of familial, personal, historical, or community-based connections, a significant portion—nearly eight thousand people out of a population of between fifty thousand and eighty thousand—of the Indian Ugandan refugee population displaced in 1972 made their way to Canada based on the decision of a transnational leader who lived in neither Canada nor Uganda and whose claim to power came out of an unusual set of circumstances in the early nineteenth century. That leader was the Aga Khan.

On August 24, 1972, Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau issued the following statement:

For our part we are prepared to offer an honorable place in Canadian life to those Ugandan Asians who come to Canada…Asian immigrants have already added to the cultural richness and variety of our country, and I am sure that those from Uganda will, by their abilities and industry, make an equally important contribution to Canadian society.

With that, thousands of South Asians, mostly Khoja Isma’ilis (a South Asian community of Nizari Isma’ili, a sect of Shia Islam), migrated to Canada as refugees from Uganda. This was one of Canada’s first major resettlements of Muslim and non-Western refugees—and it was mostly thanks to a personal relationship between global elites: the Aga Khan IV, spiritual leader of the Khoja Isma’ili Shiites, and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau.

Trudeau’s statement had been prompted by a series of events that had occurred more than a year earlier. General Idi Amin ousted Milton Obote, Uganda’s first prime minister and second president, in a January 1971 military coup. Obote had been in power since the country’s independence in 1962, and in the years preceding the coup, Amin and Obote found themselves at loggerheads. While Amin gained popularity as the leader of an increasingly powerful armed forces, Obote attempted to assert and consolidate his own authority through his socialist Move to the Left policies, which included a proposed national service mandate and the takeover of corporations by the state. After rumors spread that Obote supporters in the army planned to arrest Amin, Amin seized the opportunity to take power when Obote visited Singapore in early 1971.

In the preceding years, Obote tried to promote African nationalism through a series of measures that sought to decenter citizens and workers perceived to be foreign, including a regime of permits and licenses meant to curtail the economic activity of noncitizens. Amin accelerated these policies, first through a census of the resident Indian population and then in their complete removal. On August 5, 1972, Amin gave a televised speech announcing his intent to expel Uganda’s Asian Indian residents, most of whom had settled in East Africa over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Uganda, he declared, would be for African Ugandans.

“Asians came to Uganda to build the railway,” he said, referencing the construction of the British-owned Uganda railroad in the 1890s. “The railway is finished. They must leave now.” They had ninety days to get out.

The Khoja Isma’ili community in Uganda numbered perhaps fourteen thousand at the time of Idi Amin’s coup. The Khojas hailed from western India—mainly Gujarat, but also Sindh and Maharashtra. The formation of their community dates back to the fourteenth century, when Nizari Isma’ilis (who believe that the eldest son of the sixth imam was the rightful heir to the imamate) migrated from Syria and Persia to western India. Many Hindus who converted to Isma’ilism were of higher, mercantile castes, and they created a syncretic religious practice that combined many elements of Hinduism with Shia Islam. The Nizari Isma’ili community looks to the Aga Khan as their spiritual and temporal leader, but this was not always the case.

The title Aga Khan—which translates roughly as “lord and master,” according to the Isma’ili scholar Farhad Daftary—dates back only to the early nineteenth century. Shah Khalilullah III, the father of Hasan ali Shah (Aga Khan I), became the first Isma’ili imam in nearly five centuries when he was granted the imamate in 1792 with political support from the Persian Qajar monarch Fath Ali Shah. Shah Khalilullah was murdered in 1817 by a mob in Yazd following a dispute between his followers and local shopkeepers. Fath Ali Shah then bestowed upon Hasan Ali Shah the honorific title Aga Khan, as well as the governorship of Mahallat and Qom. When Fath Ali Shah died, he was succeeded by his grandson Muhammad Shah. Muhammad Shah granted Aga Khan I the additional governorship of Kirman in 1835; despite calming a rebellion against Qajar rule, Aga Khan I was dismissed from the position two years later. Thus began his campaign against Persian rule. Claiming he was fighting for liberation, Aga Khan I stated in a letter to the British that his goal was to assist “all the respectable people and nobles of Persia…to recover their privileges, so that the tyranny of the government might cease and the people of the county might not be destroyed.”

It was in this context that the Aga Khan’s alliance with the British was born. In the early 1840s Aga Khan I met up with Henry Rawlinson, the British consul in Baghdad. Rawlinson saw the potential for an alliance that could destabilize a Persian state seeking to expand into Afghanistan, an important buffer zone between British India and the Middle East. The Aga Khan’s immense wealth and access to soldiers, he thought, could be deployed as a tool in the British colonial arsenal. After Rawlinson wrote to William Hay Macnaghten, the British envoy in Kabul, the pair agreed on a pension of three thousand rupees a month for Aga Khan I and his soldiers. For his part, the Aga Khan foresaw nothing less than the complete annexation of Persia for the British.

When the British departed Afghanistan in 1842, Aga Khan I moved from his outpost in Afghanistan to Sind and assisted the British there and in Baluchistan. By 1845, however, the British seem to have tired of his abilities as a military aide. Aga Khan I was encouraged to resettle in Calcutta if he wished to continue to receive state support. He later settled in Bombay, where there was a large community of Khoja families who had moved from western India and become quite successful in various mercantile trades.

No longer a soldier and by then mostly ignored by the British, Aga Khan I pivoted from would-be conqueror to spiritual and religious leader. He viewed himself as royalty; during a visit, Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, called the Aga Khan “His Highness.” He declared himself the leader of the Khoja community worldwide and—given his title as imam and his wealth—was able to do so. His ascension to power culminated in an 1861 decree requiring all Khojas to sign a declaration that he was their Shia leader and they should look to him for spiritual and temporal rule. Nearly 1,700 Khojas, the majority of the population, signed the document.

The few Khojas who refused to sign the announcement challenged the Aga Khan’s control over the collective property of the community, a dispute that eventually entered the British colonial courts. In what is now known as the Aga Khan case, the British held that Hasan Ali Shah was the rightful leader of the Khoja community and that all Khojas were his followers. The Aga Khan was now legally recognized as both the religious and political leader of a community.

The ruling created a mutually beneficial arrangement for Britain and the Khojas. The wealthy mercantile community of Bombay Khojas now had a leader who was well connected to the British, who in turn found it useful to have a well-established community organized under a leader over whom they could exercise a measure of control. In this moment of colonial rule several interests seem to have intersected at once and in the process helped to create a leader for a community that stretched from Bombay all the way across the Indian Ocean to East Africa.

Khoja Isma’ilis began to settle in Zanzibar in the early sixteenth century as part of Indian Ocean trading networks connecting western India with East Africa. Migration along these networks began to increase in the early nineteenth century, partially due to the encouragement of the Omani sultan Said ibn Sultan. The sultan heavily relied on Indian advisers, and when he moved the capital of his empire to Zanzibar, he turned to Indian merchants to run the increasingly profitable slave trade based on the archipelago. After the British exerted pressure on Zanzibar to cease participating in the slave trade, many merchants shifted to the sale of ivory.

By the time Uganda was formally annexed into the British Empire in 1893, there were two streams of migration to Zanzibar, Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya. The first group mainly consisted of merchants. The average emigrant to East Africa would have been moderately wealthy; he either had to pay his fare to cross the Indian Ocean or find a sponsoring group in East Africa to help subsidize his trip. For that reason alone an organized Khoja Isma’ili community was indispensable, allowing established artisans and traders to sponsor kith and kin.

Unskilled laborers brought as indentured servants to build the British-owned Uganda railroad made up the other group. From 1896 to 1901 a total of 31,983 workers arrived on three-year contracts. At the end of their terms, they were eligible for a free return back to India or they could remain. Nearly 80 percent of the workers went back to India, but nearly seven thousand chose to stay.

When Idi Amin pointed out that the railroad had been completed in the 1890s and declared that the Indians must leave, he not only dismissed the Ugandan Indian presence as only that of contract laborers but also ignored both the descendants of indentured servants and those merchant families who had roots in the country going back 150 years. He made no differentiation among these groups and insisted all had to depart the country.

Aga Khan I died in 1881, and his son Aga Khan II held the role for only four years until his own death in 1885. Aga Khan III, born and raised in Bombay, became imam at seven years old. As a young man, he enthusiastically made connections with European and Ottoman royalty and later moved his family to Europe, settling in Switzerland and maintaining a residence on France’s Mediterranean coast.

At the same time the Isma’ili community in East Africa was gaining power and organizing into a community with a significant amount of power and wealth. As the British expanded colonial control further into the interior of East Africa, the Khoja Isma’ilis often followed, with Aga Khan III drawing explicit parallels between the Khojas’ settlement in East Africa and the American colonization of the West. Because the Aga Khan held title to all communal Khoja property, whether in India or abroad, the community’s expansion increased his fortunes even from his home in Europe.

Aga Khan III established social services across Isma’ili East Africa, including housing societies, health care facilities, libraries, and schools, that benefited both the Isma’ili community and African Ugandans, though financial opportunities such as access to capital and insurance were reserved for Isma’ilis. By 1926 the Aga Khan had set up a system of councils to govern and provide the community with education, loans, health care, and employment. What emerged out of the Aga Khan’s leadership was a highly centralized and tight-knit community of well-off traders and artisans.

Through its access to networks of power during British colonial rule, the Khoja Isma’ili community became a global and cosmopolitan nexus of mercantile power. Yet they were just one group among many in the local Indian community, and there were others with similar stories of economic success. South Asians in Uganda as a whole were a minority group with economic power—an easy target for resentment that could be exploited by a nationalist despot.

Responsibility for the Khoja community in Uganda at the time of expulsion fell upon Aga Khan IV, who assumed the imamate in 1957 while completing his undergraduate degree at Harvard. It’s unclear when Aga Khan IV and Pierre Trudeau first met, but after Trudeau’s death in 2000, the Toronto Star reported that Aga Khan IV had been friends with Trudeau for thirty years and that Trudeau had twice vacationed on his yacht. Aga Khan IV remains friends with Trudeau’s family, and in 2017 undeclared gifts, private island vacations, and flights tied to the relationship created a scandal for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, Pierre’s son.

While there is no record of a phone call, Aga Khan IV was said to have personally reached out to Pierre Trudeau, asking him to intercede on behalf of the Isma’ili community in Uganda. Aga Khan IV later recounted:

Pierre and I were friends, and there was an informal understanding that if there was a racial crisis, Canada would intervene. So when Uganda’s Idi Amin decided in 1972 to expel Asians, I picked up the phone, and Trudeau affirmed then and there that Canada would wish to help. His response was magnificent.

An official Canadian refugee policy had been put into place in 1969 after Canada finally entered into the 1967 United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees and the previous 1951 UN Refugee Convention, which had recognized only those whose status had come about “as a result of events occurring before January 1, 1951,” and reserved a nation’s right to interpret the convention as limited to refugees from Europe as a result of World War II. Decolonization across the globe led to the removal of both restrictions in the 1967 protocol. While Canada adopted the UN’s definition of a refugee, Canada relied on a points-based system for immigration, weighing factors such as English-language knowledge, education, and access to capital. The same standard was applied to select refugees for resettlement, though some leeway was given to immigration officials to consider humanitarian reasons to allow admittance for those who did not satisfy the points criteria. Cabinet meetings discussing the Indian expulsion highlighted the importance of these humanitarian concerns, and the conclusion was to give Canadian immigration officials in Uganda significant leeway to determine who qualified for resettlement regardless of points. The Canadians set up a remarkably efficient operation for Indian Ugandans, issuing visas for 6,292 people (though 117 were never claimed). Over the next two years, Canada also accepted 2,000 Indians who had ended up in refugee camps in Europe.

Of the nearly eight thousand Ugandan refugees settled in Canada, more than 50 percent were Isma’ili. To this day, the narrative around Indo-Ugandan resettlement in Canada privileges this community, making it difficult to ascertain much about the rest of the Ugandan refugees. Another group of over 27,000 refugees were settled in the United Kingdom, while 4,500 went to India. Despite the fact that a majority of the refugees in Canada were of Khoja Isma’ili origin, it’s difficult to ascertain whether they were privileged for Canadian resettlement. Michael Molloy, one of the Canadian immigration officials in charge of setting up refugee operations in Uganda, wrote an essay for the 2021 book Finding Refuge in Canada: Narratives of Dislocation in which he said that officials in Kampala “were unaware of any controversy surrounding the role of the Aga Khan or his representatives in the selection of refugees.” Molloy said that the priority was the efficient processing of visas, rather than resettling one specific subset of Ugandan society in Canada. No one at the time seems to have pointed out that most of the refugees were of Isma’ili origin.

Whether due to their transnational connections or otherwise, the community thrived. There are about a hundred thousand Isma’ilis in Canada today, and Aga Khan IV was named an Honorary Canadian in 2010. Many of them have assimilated but remain part of the global Isma’ili community. Some have become quite successful and are grateful to their host country. For example, the lawyer Jalal Jaffar QC reflected in his memoir Memories of a Ugandan Refugee: Encounters of Hope from Kampala to Vancouver, “Whilst we might, once in a while, think of the brutality and the choke hold Idi Amin had over all the Asians in Uganda, such thoughts quickly recede from our consciousness when we remind ourselves the humane embrace laid out by Canada.”

While researching historical material that would later make its way into Mother Ocean Father Nation, I was interested in narratives of expulsion and resettlement. The novel follows a brother and a sister who are separated—the brother stays behind while the sister is forced to flee to California, her life put on pause as she struggles for legal recognition of her asylum status. I sought out narratives of dislocation in order to find the interior life of a political fracture with a long history: racial animus created by a colonizing empire that found its apogee in a military coup.

My novel attempts to convey to the reader that there is no singular narrative of this experience. In the case of Indian Ugandans resettling in Canada, a well-connected spiritual and political leader could help move thousands across the globe. It’s a reminder that the strange and circuitous histories that began in the colonial era echo later not only as coups and expulsions but also as pathways for escape and growth.

Explore Migration, the April / May 2022 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.