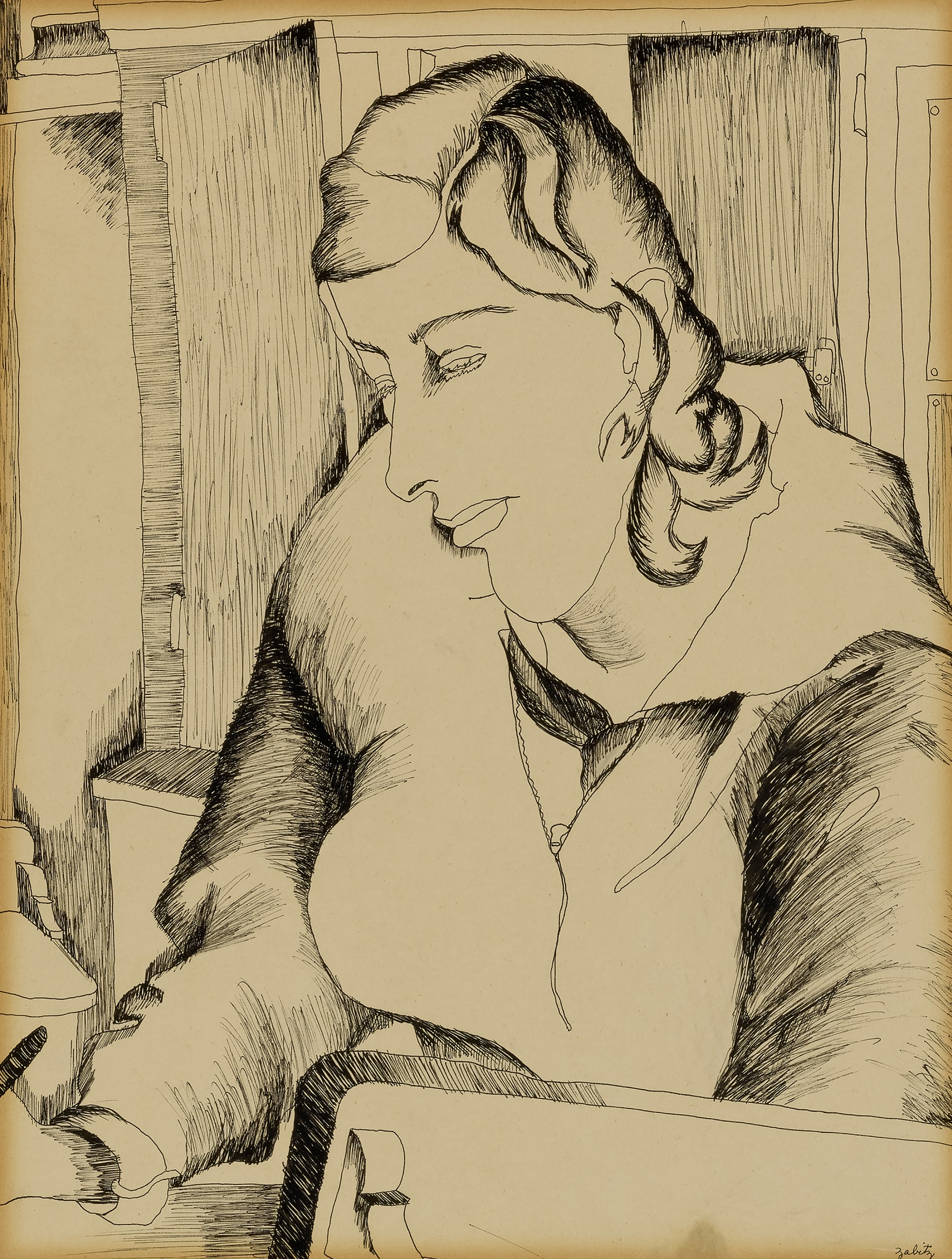

Woman Writing, by Zabitz. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the Evander Childs High School, Bronx, New York through the General Services Administration, 1975.

I shall be a best-selling author. After Imago each of my books will be on the best seller lists of LAT, NYT, PW, WP, etc. My books will be read by millions of people. I will buy a beautiful home in an excellent neighborhood. I will help poor black youngsters broaden their horizons. I will find a way to do this. So be it. See to it!

Octavia Butler wrote these prescient, earnest, and deeply personal ambitions into existence in one of her countless diaries. I envision the novelist contemplating every word as her pen pressed against the crisp white pages, especially in emphasizing those last three words. When she used her typewriter, as she sometimes did, I hear the sharp clicking of the keyboard that would stop only when Butler pulled out a completed page and looked over the goals she knew were hers to reach. Writing her aims down was simply the first step in making them tangible achievements. She would do this, somehow, some way—she would see to it, and her diaries would be her first witnesses.

The act of journaling or keeping a diary has historically never been an inclusive club, keeping out plenty of people who had interesting lives or thoughts worthy of becoming a keepsake. From the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, literacy, leisure, and access to paper and candles were rare privileges constrained within the boundaries of race and gender, and so it was often intellectual white men who documented the reality of the places they lived in: the social upheaval, educational failures, and perceived injustices. Though men formed the majority of respected writers, women presented their own personal reflections between the pages of their small books, too. Boston native Katharine Greene Amory kept a journal spanning the years 1775–77 in which she wrote about her life in the backdrop of the American Revolution. Her loyalist leanings placed her writings in a space that has since drawn attention from historians and researchers eager for a viewpoint that seemingly went against the grain. Harriet Arbuthnot, a well-known figure in early nineteenth-century English political circles, was a diarist whose entries on figures such as the Duke of Wellington, the Duchess of Kent, and a young Queen Victoria offered a more humane look at people largely beyond public reach. Arbuthnot had almost unfettered access to members of the British elite, and she spent much of her time making observations that she would later candidly record in her diaries. Amory and Arbuthnot were the prototypes setting expectations for the kind of women who kept diaries; as astute as their writings were, men remained the dominant voice.

The diaries and journals of people of color and specifically black women are rarely included in the public discourse. These were people who were often prohibited by law from taking part in history making. In 1780 South Carolina became one of the first states to pass legislation prohibiting the education of African Americans, whether enslaved or free. While one of the tenets of slavery was ensuring the illiteracy of those enslaved, in another part of the world a colonial white minority government left black people with pens and papers as one of the few avenues of resistance. During the forty-six years of apartheid rule in South Africa, educational opportunities and resources offered to black students were limited and subpar, compelling fourteen teenagers from the poor neighborhood of Soweto to write their daily observations in their diaries. From July to October 1982 seven boys and seven girls between the ages of twelve and fourteen meticulously compiled and reported on the realities around them along with the wider effects on their communities. In 1988 their words were published in Give Us a Break: Diaries of a Group of Soweto Children. Yet little is known of the literary journeys of these young archivists before and after the book’s release.

When it comes to posterity, diaries are an intimate approach at grasping testimonies that are both personal and foundational while also being communal. In the world of black women writers, tucked in these small notebooks is their solace, bone-deep longing, and informed examinations of the places they worked hard to thrive in—and a place where they could discard conventional notions and engage with the brutal, fragile, eerie, and unfamiliar.

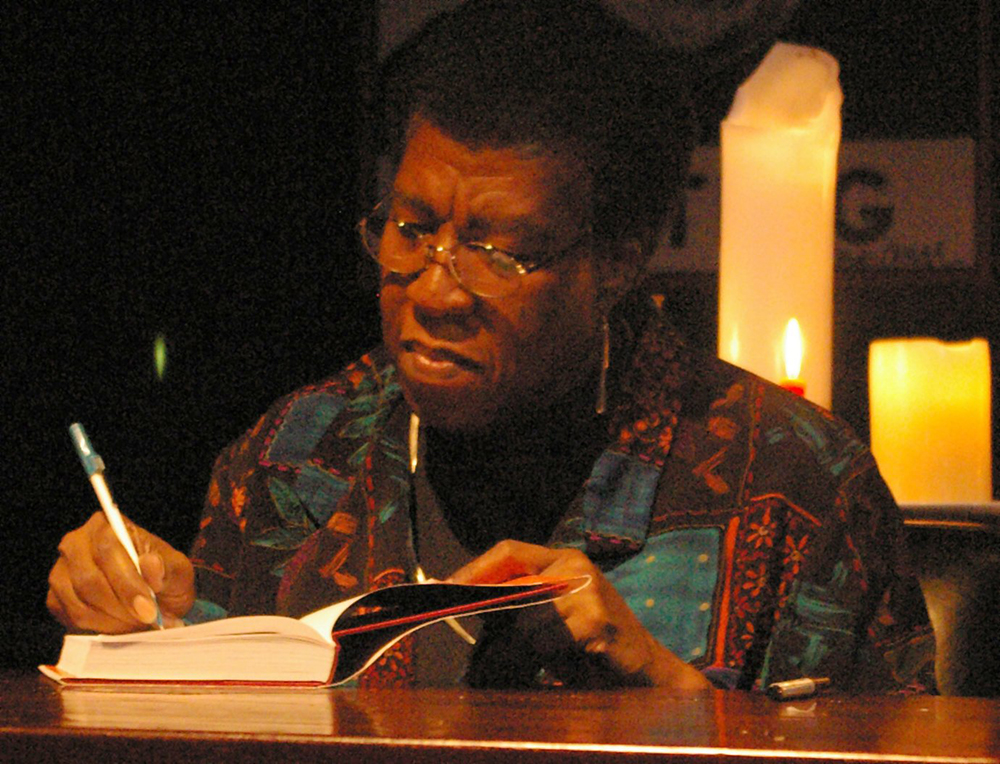

Butler was a self-confessed hermit, a woman who found her own company most appealing after surviving childhood bullying. She craved solitude even as she worked toward becoming one of the world’s most successful authors, and her diaries held the contradictions of an artist deeply devoted to her craft but weary from rejections and moments that found her unable to foster inspiration. “Mental rehearsal, time management, concentrated sustained attention” were the reminders she wrote under her “Essentials of Success” list, which was right next to a single phrase posted on the left side of a page: “All good things must begin.” It’s a phrase that fits so perfectly with Butler’s bibliography; although most associated with prophetic dystopian universes, her books also lean heavily on the potential of new beginnings. The Xenogenesis series, along with Parable of the Sower, Wild Seed, and her last novel Fledgling, all dealt with varied concepts of regeneration and rebirth. Even the titles lend themselves to images of things not yet begun but with the capacity of becoming. Whether their becoming would also be their undoing is arguable, but what’s clear is that Butler meditated intentionally and constantly on growth—her own and that of the characters she created.

Reading the words in Butler’s diary feels less intrusive and more revelatory. They belong to a record of posthumous notes from women whose work and identity were constantly disfigured at home and the workplace, yet who retaliated with unceasing documentation of the mundane and profound ideas that kept them up at night or amused their spirits. Their diaries illuminated what society refused to make room for: the heavy, complicated, existential, capricious, and vulnerable confessions of black women. Their diaries solidified memory, and in hindsight writing them seems to be an unconscious act of self-preservation. Consciously or not they wrote their own life plans, best wishes, healing sessions, and—in a twist that’s both beautiful and profound—even their own eulogies. We remember them because they never forgot themselves.

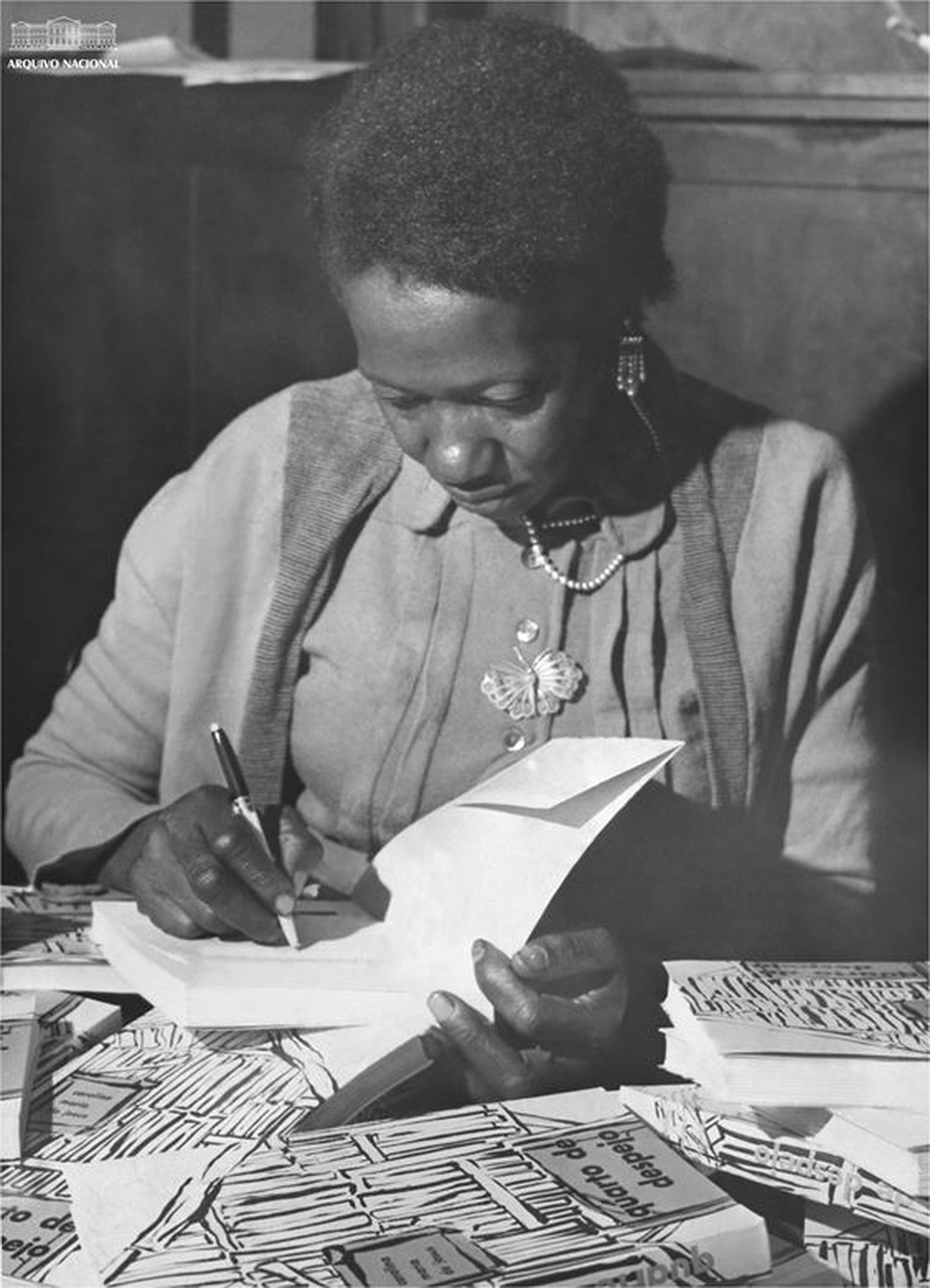

Afro-Brazilian author Carolina Maria de Jesus first started writing on scraps of paper she found while rummaging through the garbage searching for goods to barter. A poor woman who lived in one of the most impoverished neighborhoods in São Paulo, de Jesus wrote for the love of it—and because she needed something to do other than take care of her three children. She also wrote because she did not want to forget the things she saw and the hardships faced by those around her. Incessant worry about adequate shelter, the men with roaming eyes and the women whose hearts were too big, the children who were beaten by their parents or the other way around, and the constant specter of hunger were all things she put to paper.

In 1960 her debut, Quarto de Despejo, translated as Child of the Dark, was published, drawing from several of her diaries from 1955 to 1960. De Jesus released her work during a time of economic prosperity, which made the poverty she described that much more startling and hard to ignore. She wrote without restraint in a Brazilian literary industry that viewed an author’s self-confessed objectivity and emotional concealment as respectable. “I am starting to lose my interest in life,” she wrote on May 19, 1958. “It’s beginning to revolt me and my revulsion is just.” These lines were bookended by musings on patriotism and the birdsong she heard while doing chores in her small shack. The monotony of her depression and the lucidness of her critiques of social policies scandalized Brazil’s upper middle class, who had until then enjoyed the privilege to forget about the black and poor who lived among them.

Becoming an author made her a temporarily wealthy woman. De Jesus’ success was short-lived, undermined by rampant anti-blackness and sexism that was compounded by a parasitic and voyeuristic interest in the lives of the poor. But Quarto de Despejo, which literally means “Room of Garbage,” was a physical testament to her memories, illustrating a fractured Brazil leaving its most marginalized citizens to drown in filth and social contempt. When de Jesus passed away in near poverty in 1977, she left behind fifty-eight boxes of work which contained completed and uncompleted plays, novels, and poems, along with recordings of her music. Of her published works, there is one book of poetry, four essay collections, and a novel. The remaining three are diaries, not including Quarto de Despejo. This was the medium she came back to often, and it’s her diaries that have remained most beloved, because it was where she placed the truths she held dear.

I know there exists Brazilians here inside São Paulo who suffer more than I do…So as not to see my children hungry I asked for help from the famous social services. It was there that I saw the tears slipping from the eyes of the poor. How painful it is to see the dramas that played out there.

De Jesus wrote this a few days after coming across the bloated corpse of a young black boy from the favela who had been poisoned by meat he’d found in the garbage. Local butchers were known to douse discarded meat with poison to dissuade favela dwellers from eating it. “His toes were spread apart. The space must have been eight inches between them. He was buried like any other ‘Joe,’ ” she wrote. “Nobody tried to find out his name. The marginal people here don’t have names.” Her unsanitized recollections are a mirror that highlighted, sometimes in graphic detail, the dark corners of Brazilian society. De Jesus’ diaries acted almost as journalistic correspondence, dispatches from a part of society so rarely covered by mainstream media. Today they continue to refract the country’s false notions of a harmonious racial mosaic.

Kathleen Collins was another prolific diarist. In February of this year some of her writings were published in Notes from a Black Woman’s Diary, a nearly five-hundred-page book containing short stories along with a play on the effects of racism and sexism on a middle-class black family living in mid-century America. Her words resonate because of their radical self-interrogation, unexpected playfulness, and tenderness toward the inner workings of her psyche. “I could have occupied myself with race all these years,” Collins wrote in an entry from the mid-1970s. She was in her early thirties, with two infant children, a rocky marriage, and a deep interest in the types of intimacy black women could foster in a society determined to render them objects as opposed to subjects.

I could have explored myself within the context of a young black life groping its way into maturity across the rising tide of racial affirmation. But I didn’t do that. No, I turned far inside, where there was only me and love to deal with. Instead of dealing with race I went in search of love…and what I found was a very hungry colored lady.

I could never have fathomed this hunger, this deep voraciousness to love and be loved, in Collins’ work. What she put out into the world felt complete and from the mind of someone who was content and full. This hunger comes to light only in her daily thoughts, where readers discover a woman who spent a lifetime learning to balance having little when she craved so much more: more love, more work, more time.

So much of what Collins produced was inspired by her closest companions, many of whom were also black artists. She and Butler especially were kindred spirits, one on the West Coast, the other on the East; their creative minds meandered toward each other in intricate and revealing ways. Butler’s “See to it!” note, on making her work happen no matter what, mirrored the words of Collins. “There is no such thing as a helpless black woman,” she wrote. “There was only one dominant theme in my childhood: holding on, no matter what…shifting and turning and choreographing and juggling and manipulating life to stay inside it! I don’t know how to be helpless. I don’t know how not to make things work.” Both Butler and Collins relied on self-motivation for sustenance and survival. A century earlier, another diarist had looked to a more omnipresent being for her own direction.

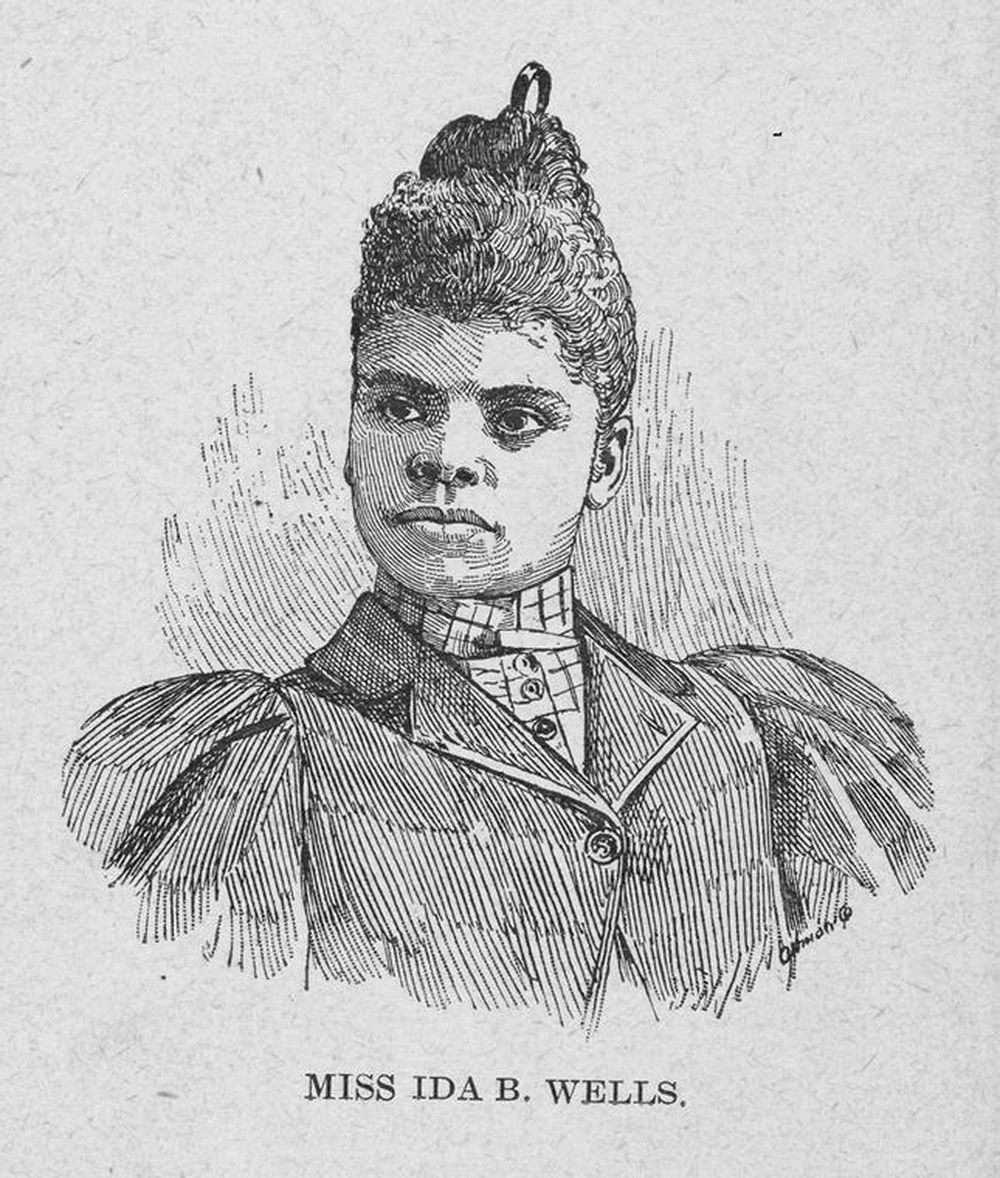

To think of Ida B. Wells today is to know of a woman whose unflinching belief in justice left no room for doubt. The journalist and activist documented the vicious cruelty of lynching throughout her career, traveling the U.S. and highlighting white supremacy across the states. It was emotionally grueling work made all the more difficult by the constant shadow of white rage. Wells’ diaries, published in 1995 as The Memphis Diaries of Ida B. Wells, showed the heart of a fighter whose unyielding faith was the fulcrum that held her upright. “The old year has gone, the new year has taken its place,” she wrote on New Year’s Day in 1886.

The book of the sins, follies, good deeds has been closed and sealed away forever…only God knows what is to be recorded here. I go forth on the pilgrimage of this new year with renewed hope, vigor, a remembrance of the glorious beginnings. And humbly pray for humility, wisdom, success in my undertakings if it be My Father’s good pleasure. And a stronger Christianity that will make itself felt.

Wells was twenty-three. Two years earlier she had sued Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad for discrimination after being dragged off a train by a conductor and two men for refusing to give up her seat in the first-class section. Wells won her case at the local circuit level, with a newspaper account labeling her case “A Darky Damsel Obtains a Verdict for Damages Against the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad.” The decision was later reversed by the Tennessee Supreme Court, a verdict that left her in despair.

In 1894, ten years after the case and while on an anti-lynching speaking tour in England, Wells wrote an opinion piece for the Birmingham Daily Post responding to a white English council member who did not see the use of African Americans visiting the city of Birmingham to publicize the prevalence of lynching in U.S. southern states. “My time is valuable, my powers are limited, and I feel justified in asking what possible, practical object can be obtained by such meetings,” the councillor wrote. Wells had personally experienced the horror of lynching and white mob violence two years earlier, when her close friend Thomas Moss and two other black men were killed by a mob of masked white men. Wells was godmother to Moss’ daughter, and after his murder she wrote an article in the newspaper Free Speech urging African Americans to leave Memphis, the city where the crime had occurred and where Wells was living at the time. It was Moss’ murder that drove her to write almost exclusively about lynching and its effects on black families. In the Daily Post, she wrote about the culpability of law officials who either did nothing or willfully took part in the crime:

The latest culmination of this war against negro progress is the substitution of mob rule for courts of justice throughout the South. The judges, juries, sheriffs, and jailers in these states are all white men and thus make it impossible for a negro to escape the penalty for any crime he commits.

She went on to detail the absence of competence in all systems, including among the officers entrusted to determine an accurate and complete cause of death. “A coroner’s jury renders a verdict that ‘the deceased came to his death at the hands of parties unknown to the jury.’ ”

Publicly Wells wrote blistering pieces on antiblack racism, but in her diaries this seemingly implacable women detailed the simple and quotidian details of her life. “Friday was a trying day in school. I know not what method to use to get my children to become more interested in their classes.” She wrote of this nearly universal parental struggle in her cursive, letters flowing into one another that are hard to read and give the impression that Wells wrote as quickly as the thoughts came into her head. Here she was a mother trying to find ways to reach her children, an advocate working for her people, and a devout Christian asking for answers.

The role of faith in Wells’ life was one of possibility and endurance, and it’s intimately recorded in her diaries. She lived an exposed life, but so often she was a solitary figure whose work kept her on the road, far from friends and her two daughters. Her decision to write down the most sensitive of her fears and doubts preceded the recording that would be done by Collins, Butler, and de Jesus, who also found a space to reckon with their fraught realities by retreating into the safety of their diaries. Here there was no judgement, accusation, or resistance. It was a place of flow and ample space to simply be. Wells’ diaries centered her convictions, and—like the black women who would find their footing in the imprints she left behind—they were a witness and a haven.